Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Landscape Report: Just as sure as you try to predict the weather, it is likely to change. But going out on a limb, I predict that we will have a bit of a dud for fall color display this year. Not a very risky prediction, considering that many plants already are starting to turn color and/or drop leaves in some areas of the state.

Nyssa sylvatica (black gum) showing early fall color due to drought stress. Source

So why would the colors be early and/or a bit duller than usual? Certainly, some of the reason why plants display fall colors has to do with the genetic makeup of the plant. That doesn’t change from year to year. But the timing and intensity of fall colors do vary, depending on factors such as availability of soil moisture and plant nutrients, as well as environmental signals such as temperature, sunlight, length of day, and cool nighttime temperatures.

The droughty conditions experienced during much of the second half of summer are likely to have decreased the amount of fall color pigment. Southern Indiana has been particularly parched. Despite recent rains in some areas, much of the state remains designated as abnormally dry to moderate drought. You can check your area’s conditions at the US Drought Monitor for Indiana. Additional maps and data is available at the Midwest Regional Climate Center.

Growing conditions throughout the season affect fall color as does current weather. Colors such as orange and yellow, which we see in the fall, are actually present in the leaf all summer. However, those colors are masked by the presence of chlorophyll, the substance responsible for green color in plants during the summer. Chlorophyll allows the plant to use sunlight and carbon dioxide from the air to produce carbohydrates (sugars and starch). Trees continually replenish their supply of chlorophyll during the growing season.

As the days grow shorter and (usually) temperatures cooler, the trees use chlorophyll faster than they can replace it. The green color fades as the level of chlorophyll decreases, allowing the other colored pigments to show through. Plants that are under stress–from conditions like prolonged dry spells–often will display early fall color because they are unable to produce as much chlorophyll.

Yellow, brown and orange colors, common to such trees as birch, some maples, hickory and aspen, come from pigments called carotenoids, the same pigments that are responsible for the color of carrots, corn and bananas.

Red and purple colors common to sweet gum, dogwoods and some maples and oaks are produced by another type of pigment called anthocyanin, the pigment responsible for the color of cherries, grapes, apples and blueberries. Unlike chlorophyll and carotenoids, anthocyanins are not always present in the leaf but are produced in late summer when environmental signals occur. Anthocyanins also combine with carotenoids to produce the fiery red, orange, and bronze colors found in sumac, oaks, and dogwoods.

Red colors tend to be most intense when days are warm and sunny, but nights are cool–below 45º F. The color intensifies because more sugars are produced during warm, sunny days; cool night temperatures cause the sugars to remain in the leaves. Pigments are formed from these sugars, so the more sugar in the leaf, the more pigment, and, thus, more intense colors. Warm, rainy fall weather decreases the amount of sugar and pigment production. Warm nights cause what sugars that are made to move out of the leaves, so that leaf colors are muted.

Leaf color also can vary from tree to tree and even from one side of a tree to another. Leaves that are more exposed to the sun tend to show more red coloration while those in the shade turn yellow. Stress such as drought, poor fertility, disease or insects may cause fall color to come on earlier, but usually results in less intense coloration, too. And stress or an abrupt hard freeze can cause leaves to drop before they have a chance to change color.

So far, weather conditions lead me to think this will be one of those not so showy fall color years. I hope I am proven wrong!

Resources

Why Leaves Change Color, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Why Leaves Change Color, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area

B. Rosie Lerner, Retired Extension Consumer Horticulturist

Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture

Cities and towns in the U.S. contain more than 130 million acres of forests. These forests vary extensively in size and locale. An urban forest can describe an urban park such as Central Park in New York City, NY, street trees, nature preserves, extensive gardens, or any trees collectively growing within a suburb, city, or town. Urban forestry is the name given to the care and maintenance of those ecosystem areas that remain after urbanization. Data from the 2010 census indicated more than 80% of Americans live in urban centers with a population increase greater than 12%. The population of Indiana represents only 2.1% of the nation. In the last 8 years, IN has had an influx of 200,000 people which represents a population increase of 3.0%!

Urban forests, which help filter air and water, control storm water runoff, help conserve energy and provide shade and animal habitat must be maintained. As our nation becomes more urbanized, appreciate those urban foresters working to ensure we have save urban forest spaces to enjoy. These precious resources add more than curb appeal and economic value, they improve our quality of life.

What does an urban forester do? Here’s a quick answer:

References:

Purdue Urban Forestry & Arboriculture, Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

USDA Forest Service Urban Forests, United States Department of Agriculture

US Census Bureau, United States Census Bureau

Interested in Purdue Urban Forestry? Contact:

Lindsey Purcell, Chapter Executive Director

Indiana Arborist Association

Ben McCallister, Urban Forestry Specialist

Forestry and Natural Resources

Resources:

Tree Support Systems, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Corrective Pruning for Deciduous Trees, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

What plants can I landscape with in area that floods with hard rain?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Extension

Deer that die from EHD are often found around water. This deer was found in August 2019 in Crawford County and was likely killed by EHD. Photo courtesy of Brody Wade.

Be on the watch for deer with EHD in Indiana

Recently, a white-tailed deer in Clarke County Indiana tested positive for Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD), and potential EHD cases have been reported in 26 other Indiana counties. Here are a few things you should know about how EHD, how to spot it, and how to report it.

What is EHD and BTV?

Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue virus (BTV) are viral diseases, collectively called hemorrhagic diseases (HD), and are common in white-tailed deer. Both diseases are transmitted by biting midges often called “no-see-ums” or gnats. Neither disease is a human health issue, but they can cause significant mortality in white-tailed deer. Outbreaks of HD tend to impact deer populations locally, meaning an outbreak may occur in one part of a county but not in other parts.

When do EHD outbreaks occur?

EHD and BTV outbreaks often occur in late summer and early fall (August-September), especially in years with drought-like conditions. Drought causes water sources to shrink, which creates warm, shallow, and stagnant pockets of water creating ideal breeding habitat for the midges that transmit EHD. Deer also congregate in these areas to find water, which helps the midges pass the disease between infected and healthy deer. EHD outbreaks can last until a frost that kills the midges.

What are the signs of a deer with EHD?

Deer with EHD often appear weak, lethargic, and disoriented. Other signs of EHD in deer are ulcers in the mouth or on the tongue, swollen face, neck, or eyelids, and a bluish color to the tongue. Deer with EHD often search for water to combat the fever caused by the disease. EHD can be confirmed by testing blood and tissue (i.e., spleen) samples, but samples must be collected shortly after death.

Where am I likely to find a deer with EHD?

Because deer with EHD often seek out water to combat the resulting fever, deer killed by EHD are commonly found around water. If you have a stream, creek, river, or other source of water on your property, looking in the vicinity of those areas can help you locate deer that have succumb to EHD.

What do I do if I find a deer I think has EHD?

If you come across a sick or dead deer that you think has EHD you can report it through an online reporting system run by the Indiana DNR. Here is a link to the reporting system: Report a Dead or Sick Deer.

Can deer survive an EHD outbreak?

Yes, some deer will survive EHD. While up to 90% of deer that contract EHD may die from the disease, the deer that survive build up antibodies to EHD, which may make them immune to future outbreaks. Additionally, does may pass the antibodies and immunity to their offspring.

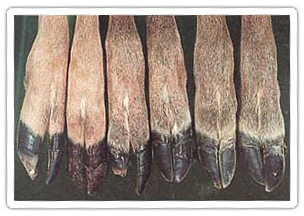

Sloughing or splitting hooves on two or more feet of a deer taken during the fall hunting season are typical of chronic HD. Photo courtesy of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study.

How can I tell if a deer I killed during hunting season has survived EHD?

If you kill a deer during the hunting season this year, pay attention to the hooves. Deer that survive an EHD outbreak often have indentions or cracks on their hooves (see picture).

Sloughing or splitting hooves on two or more feet of a deer taken during the fall hunting season are typical of chronic HD. Photo used courtesy of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study.

Are deer that have survived EHD safe to eat?

Yes, deer that have survived EHD are safe to eat.

For updated information on EHD in Indiana check out the Indiana DNR – Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease web page.

Resources:

Report a Sick or Dead Deer, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN-DNR)

EHD Virus in Deer: How to Detect and Report video, Quality Deer Management Association

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease, Cornell University

How to Score Your White-Tailed Deer video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Playlist

Deer Harvest Data Collection, Purdue FNR Got Nature? blog

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

One of the most dangerous pests to trees is a human, especially with equipment.  Injuries to trees caused by a lawn mower or weed trimmer can seriously threaten a tree’s health.

Injuries to trees caused by a lawn mower or weed trimmer can seriously threaten a tree’s health.

Additionally, damage to the bark layer of trees causes a long-term liability by creating a wound which leads to a defect, becoming an unsafe tree.

The site of injury is usually the root flare area, where the tree meets the turf and gets in the path of the mower or trimmer. The bark on a tree acts to protect a very important transport system called the cambium layer.

This is where specialized tubes are located which move nutrients and water between the roots and the leaves. Bark layers can vary in thickness on different tree species. It can be more than an inch in thickness or less than 1/16 of an inch on young, smooth-barked trees such as maples and birch trees. This isn’t much protection against string trimmers and mowing equipment, especially the young trees.

Any type of damage or removal of the bark and the transport system can result in long-term damage. Damage, which extends completely around the base of the tree called girdling, will result in ultimate death in a short time.

Tree wounds are serious when it comes to tree health. The wounded area is an opportunity for other insects and diseases to enter the tree that causes further damage. Trees can be completely killed from an attack following injuries. Fungi becomes active on the wound surface, causing structural defects from the decay. This weakens the tree or it eventually dies, creating a risk tree to people around it.

Newly planted, young trees need all the help we can provide to become established in the landscape and these trees are often the most commonly and seriously affected by maintenance equipment. However, injury can be avoided easily and at very low cost with these suggestions.

The removal of turf or prevention of grass and weeds from growing at the base of the tree are low-tech solutions to eliminate a serious problem. Spraying herbicides to eliminate vegetation around the base of the tree can decrease mowing maintenance costs. Be sure to use care when applying herbicides around trees.

The removal of turf or prevention of grass and weeds from growing at the base of the tree are low-tech solutions to eliminate a serious problem. Spraying herbicides to eliminate vegetation around the base of the tree can decrease mowing maintenance costs. Be sure to use care when applying herbicides around trees.- A 2-3” layer of mulch on the root zone of the tree provides an attractive and healthy environment for the tree to grow. Additionally, it provides a visual cue to keep equipment away from the tree.

- Also, trunk guards and similar devices can add an additional measure of protection for the tree. Using white, expanding tree guards can help improve the trees ability to withstand equipment contact, but also help to reduce winter injury.

Trees are a major asset to your property and important to our environment. Protect our trees and preserve these valuable assets by staying away from tree trunks with any mowing or weed trimming equipment. The damage lasts and it cannot be repaired and often results in losing your tree.

Purdue University Landscape Report Article

Resources

Corrective Pruning for Deciduous Trees, The Education Store – Purdue Extension resource center

What plants can I landscape with in areas that floods with hard rain?, Purdue Got Nature? Blog

Tree support systems, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forest Specialist

Forestry and Natural Resources

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Bulletin: USDA declares August Tree Check Month and urges public to look for Asian longhorned beetle.

WASHINGTON, July 23, 2019 — August is the height of summer, and it is also the best time to spot the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) as it starts to emerge from trees. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is asking the public to take five minutes to step outside and report any signs of this invasive pest. Checking trees for the beetle will help residents protect their own trees and better direct USDA’s efforts to eradicate this beetle from the United States.

“It’s important to look for signs of the beetle now, because it’s slow to spread during the early stages of an infestation,” said Josie Ryan, APHIS’ National Operations Manager for the ALB Eradication Program. “With the public’s help, we can target new areas where it has spread and provide a better chance of quickly containing it.”

The Asian longhorned beetle feeds on a wide variety of popular hardwood trees, including maple, birch, elm, willow, ash and poplar. It has already led to the loss of more than 180,000 trees. Active infestations are being fought in three areas of the country: Worcester County, MA, Long Island, NY (Nassau and Suffolk Counties), and Clermont County, Ohio.

“Homeowners need to know that infested trees do not recover and will eventually die, becoming safety hazards,” warned Ryan. “USDA removes infested trees as soon as possible because they can drop branches and even fall, especially during storms, and this keeps the pest from spreading to nearby healthy trees.”

The Asian longhorned beetle has distinctive markings that are easy to recognize:

- Antennae that are longer than the insect’s body with black and white bands.

- A shiny, jet-black body with white spots, about 1” to 1 ½” long.

- Six legs and feet, possibly bluish-colored.

- Round exit holes in tree trunks and branches about the size of a dime or smaller.

- Shallow oval or round scars in the bark where the adult beetle chewed an egg site.

- Sawdust-like material called frass, laying on the ground around the tree or in the branches.

- Dead branches or limbs falling from an otherwise healthy-looking tree.

After seeing signs of the beetle:

- Make note of what was found and where. Take a photo, if possible.

- Try to capture the insect, place in a container, and freeze it. This will preserve it for easier identification.

- Report findings by calling 1-866-702-9938 or completing an online form at USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

It is possible to eliminate this pest and USDA has been successfully doing so in several areas. Most recently, the agency declared Stonelick and Batavia Townships in Ohio to be free of the Asian longhorned beetle. We also eradicated the beetle from Illinois, New Jersey, Boston, MA, and parts of New York. The New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens are in the final stages of eradication.

For more information about the Asian longhorned beetle, other ways to keep it from spreading—such as not moving firewood—and eradication program activities, visit USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. For local inquiries or to speak to your State Plant Health Director, call 1-866-702-9938.

Other Resources:

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Agriculture & Indiana Invasive Species Council

Great Lakes Early Detection Network, Bugwood Apps

New Hope for Fighting Ash Borer, Got Nature? Blog

Mile-a-Minute Invasive Vine Found Indiana, Got Nature? Blog

Sericea Lespedeza: Plague on the Prairie, Got Nature? Blog

Invasive Plants: Impact on Environment and People, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Invasive Plant Species in Hardwood Tree Plantations, The Education Store

Invasive Plant Species: Callery Pear, Purdue Extension The Education Store

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Purdue Landscape Report: When was the last time you really looked at your trees? It’s all too easy to just  enjoy their cool shade and the sound of their leaves, but if you don’t know what to look for you could miss deadly diseases or dastardly demons lurking in their leaves and branches. A quick check can help you stop a problem before it kills your tree or your local forest!

enjoy their cool shade and the sound of their leaves, but if you don’t know what to look for you could miss deadly diseases or dastardly demons lurking in their leaves and branches. A quick check can help you stop a problem before it kills your tree or your local forest!

National Tree Check Month is the perfect time to make sure your tree is in tip-top shape! Our checklist will help you spot early warning signs of native pests and pathogens and invasive pests like Asian longhorned beetle, spotted lanternfly, and sudden oak death. You can stop invasive pests in their tracks by reporting them if you see them.

Is your tree healthy and normal?

Start by making sure you know the type of tree you have. Is it a deciduous tree like an oak or maple? Or is it an evergreen that like a spruce or a pine? Don’t worry about exactly what species it is. It’s enough for you to have a general sense of what the tree should look like when it’s healthy.

Check the leaves

- Are the leaves yellow, red or brown?

- Are they spotted or discolored?

- Do the leaves look distorted or disfigured?

- Is there a sticky liquid on the leaves?

- Do the leaves appear wet, or give off a foul odor?

- Are leaves missing?

- Are parts of the leaves chewed?

Check the trunk and branches

- Are there holes or splits in the trunk or branches?

- Is the bark peeling from a tree that shouldn’t shed its bark?

- Are there tunnels or unusual patterns under the bark?

- Is there sawdust on or under the tree?

- Is there sap oozing down the tree?

- Does the sap have a bad odor?

- Do sticky drops fall on you when you stand under the tree? You might have spotted lanternfly. Please report it right away!

Now what? If you answered YES to any of the questions above, there’s a good chance something is wrong. To decide if and how you should treat or report the problem, you’ll need to have a tentative diagnosis. Luckily, there are many ways to get one!

Know the tree species? Use the Purdue Tree Doctor to get a diagnosis and a recommendation on whether treating or reporting is needed. This app allows you to flip through photos of problem plagued leaves, branches and trunks to help you rapidly identify the problem. If you have an invasive pest, it will guide you how to report it.

Don’t know the tree species and still need help? Reach out to local experts. We’re happy to help!

- Purdue Cooperative Extension Service (https://extension.purdue.edu/) can answer your questions or direct you to a local tree care professional with the right expertise.

- Contact an arborist who can give you an assessment of your tree and specific treatment recommendations (https://www.treesaregood.org/findanarborist).

Confused but think something is TERRIBLY WRONG? Contact Purdue’s Exotic Forest Pest Educator, report online, or call 1-866-NOEXOTIC.

Resources:

Trees and Storms, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Why Is My Tree Dying?, The Education Store

Caring for storm-damaged trees/How to Acidify Soil in the Yard, In the Grow, Purdue Extension

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Mechanical Damage to Trees: Mowing and Maintenance Equipment, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Tree Planting Part 1 & Tree Planting Part 2, videos, The Education Store

With all of the recent rain we have had throughout the state, I have received several inquiries about effects on wildlife and what we can expect. While some flooding is natural in low areas and wildlife are adapted to respond, extreme flooding can impact wildlife. Flood waters can wash away nests or drown developing or very young animals for those living in low-lying areas. For example, heavy spring rains can reduce nest success of wild turkeys.

I have received several inquiries about effects on wildlife and what we can expect. While some flooding is natural in low areas and wildlife are adapted to respond, extreme flooding can impact wildlife. Flood waters can wash away nests or drown developing or very young animals for those living in low-lying areas. For example, heavy spring rains can reduce nest success of wild turkeys.

In many cases, wildlife will adapt by simply moving to higher ground. I tend to get an increase in inquiries about snakes after flooding. They begin showing up in neighborhood homes when they have never been observed in years past. Certainly our environment changes over time and wildlife can and do respond to these changes. However, sudden changes are likely due to a response of snakes moving to drier ground. The good news is this and other similar displacement of wildlife is usually temporary.

What can we do? I’m afraid not much for our currently flooded friends. However, in the long-term, times like this reinforce the need to create and enhance quality wildlife habitat. Providing wildlife with quality habitat that contains the necessary food, cover and water resources gives them a fighting chance to deal with issues that inevitably arise. In addition, wetlands that landowners build and restore on their properties not only enhance wildlife habitat, but also help retain moderate flood waters and recharge groundwater supplies.

If some unwanted wildlife has overstayed their welcome in and around your home, check out the Purdue Education Store publication, Considerations for Trapping Nuisance Wildlife with Box Traps. If you think you have found a sick or injured animal, you can find a list of licensed Wild Animal Rehabilitators in your area on the DNR Division of Fish and Wildlife’s Orphaned and Injured webpage. In Indiana, wildlife rehabilitators have necessary state and federal permits to house and care for sick or injured wild animals.

Additional Resources

Preventing Wildlife Damage – Do You Need a Permit? The Education Store, Purdue Extension

The Basics of Managing Wildlife on Agricultural Lands, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Brian J. MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University

Cockroaches are serious threats to human health. They carry dozens of types of bacteria, such as E. coli and salmonella, that can sicken people. And the saliva, feces and body parts they leave behind may not only trigger allergies and asthma but could cause the condition in some children.

A German cockroach feeds on an insecticide in the laboratory portion of a Purdue University study that determined the insects are gaining cross-resistance to multiple insecticides at one time. (Photo by John Obermeyer/Purdue Entomology)

A Purdue University study led by Michael Scharf, professor and O.W. Rollins/Orkin Chair in the Department of Entomology, now finds evidence that German cockroaches (Blattella germanica L.) are becoming more difficult to eliminate as they develop cross-resistance to exterminators’ best insecticides. The problem is especially prevalent in urban areas and in low-income or federally subsidized housing where resources to effectively combat the pests aren’t as available.

“This is a previously unrealized challenge in cockroaches,” said Scharf, whose findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports. “Cockroaches developing resistance to multiple classes of insecticides at once will make controlling these pests almost impossible with chemicals alone.”

Each class of insecticide works in a different way to kill cockroaches. Exterminators will often use insecticides that are a mixture of multiple classes or change classes from treatment to treatment. The hope is that even if a small percentage of cockroaches is resistant to one class, insecticides from other classes will eliminate them.

Scharf and his study co-authors set out to test those methods at multi-unit buildings in Indiana and Illinois over six months. In one treatment, three insecticides from different classes were rotated into use each month for three months and then repeated. In the second, they used a mixture of two insecticides from different classes for six months. In the third, they chose an insecticide to which cockroaches had low-level starting resistance and used it the entire time.

In each location, cockroaches were captured before the study and lab-tested to determine the most effective insecticides for each treatment, setting up the scientists for the best possible outcomes.

“If you have the ability to test the roaches first and pick an insecticide that has low resistance, that ups the odds,” Scharf said. “But even then, we had trouble controlling populations.”

For full article: Rapid cross-resistance bringing cockroaches closer to invincibility.

Resources

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Agriculture & Indiana Invasive Species Council

Purdue experts encourage ‘citizen scientists’ to report invasive species, Purdue Agriculture News

New Hope for Fighting Ash Borer, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Mile-a-Minute Invasive Vine Found Indiana, Got Nature? Blog

Sericea Lespedeza: Plague on the Prairie, Got Nature? Blog

Michael E. Scharf, Professor and O.W. Rollins/Orkin Chair

Purdue Department of Entomology

Brian J. Wallheimer, Science Writer

Purdue College of Agriculture

The Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources Extension have recently released a new publication through The Education Store. This collaborative publication is a visual identification guide on salmon and trout of the Great Lakes.

The Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources Extension have recently released a new publication through The Education Store. This collaborative publication is a visual identification guide on salmon and trout of the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes are home to eight species of salmon and trout. These species can be difficult to distinguish from each other as they overlap in their distributions and change appearance depending on their habitat and the time of year. This illustrated, peer-reviewed, two-page guide, courtesy of the Great Lakes Sea Grant Network, shows important body features and helpful tips to identify and distinguish between salmon and trout species in the Great Lakes.

View the Salmon and Trout of the Great Lakes: A Visual Identification Guide on The Education Store-Purdue Extension. See below for other related publications and websites.

Resources

A Fish Farmer’s Guide to Understanding Water Quality, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Pond Management: Stocking Fish in Indiana Ponds, The Education Store

The Nature of Teaching: Adaptations for Aquatic Amphibians, The Education Store

DNR Fish Identification Form, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, IISG Homepage

Mitchell Zischke, Clinical Assistant Professor

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Sudden oak death, as the name suggests, is a disease that is capable of rapidly killing certain species of oaks. It was first identified in California, in 1995. Two years earlier it was identified in Germany and the Netherlands, killing rhododendron. Because the pathogen originally infected and killed tanoaks, an undesirable, understory scrub tree, it generated little interest until other, more desirable oaks species began dying. However, by this point, the disease was well established and eradication no longer an option, with millions of oak trees killed by the disease. Currently, over 120 hosts in addition to oaks have been identified, and more continue to be added to this list. What is most unusual about sudden oak death is the severity of disease symptoms coupled with the broad host range of the pathogen. This leads to difficulty in diagnosing and managing this disease.

Sudden oak death, as the name suggests, is a disease that is capable of rapidly killing certain species of oaks. It was first identified in California, in 1995. Two years earlier it was identified in Germany and the Netherlands, killing rhododendron. Because the pathogen originally infected and killed tanoaks, an undesirable, understory scrub tree, it generated little interest until other, more desirable oaks species began dying. However, by this point, the disease was well established and eradication no longer an option, with millions of oak trees killed by the disease. Currently, over 120 hosts in addition to oaks have been identified, and more continue to be added to this list. What is most unusual about sudden oak death is the severity of disease symptoms coupled with the broad host range of the pathogen. This leads to difficulty in diagnosing and managing this disease.

What causes this disease?

The pathogen that causes SOD is Phytophthora ramorum (pronounced Fī-toff-thor-ă ră-mor-ǔm). This pathogen belongs to a group of organisms in the Kingdom Chromista, and has characteristics similar to fungi, plants and animals. It spreads throughout the plant by hyphal threads (like fungi), produces spores (like fungi) that have flagella and swim through water (like animals), but its cell wall is made up of cellulose (like plants). When conditions dry up, Phytophthora can produce thick walled sexual spores called oospores, or asexual chlamydospores. Because P. ramorum is not a ‘true’ fungus, many fungicides labeled for control of other fungal diseases are not effective against it.

With such a broad range of plant hosts, it is important to stress that P. ramorum affects different species in different ways. Identification must be confirmed in the laboratory and cannot be identified on field symptoms alone. Many common landscape shrubs are also infected by other endemic Phytophthora species, and symptoms look similar. Boring insects and other root rots may be mistaken for this disease. For this reason, all Phytophthora infections should be screened by the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Laboratory.

What are the symptoms of SOD?

To understand this disease, it is important to recognize that there are two categories of hosts: bark canker hosts and foliar hosts. Further complicating this is the fact that oaks are divided into three subgroups, and only the red oak group are susceptible to this pathogen. Of our 17 oak species in Indiana, half are potentially, or known to be susceptible, and include black, blackjack, cherrybark, Northern pin, pin, red, scarlet, and Shumard oaks. Diagnostic symptoms of infected red oaks include oozing sap and red-brown cankers that often leading to death.

Our concern right now is on ‘the other’ hosts. Despite its name, sudden oak death primarily spreads through foliar hosts that are sold throughout the United States. Foliar hosts include rhododendrons, azalea, viburnum, lilac, and periwinkle (Vinca minor).

These hosts (and many others) are infected via the leaves and small branches. These infections rarely cause death, and can be mistaken for sunscald, twig canker, and dieback caused by other pathogens, including native Phytophthora species. Although symptoms from these infections are not severe, and are rarely fatal, the infections produce enormous numbers of spores that can infect neighboring, susceptible oaks—and other plant species. For this reason, we are asking people to examine any rhododendrons (or other co-mingled hosts like azalea, viburnum and lilac) purchased this spring from Walmart and Rural King, while the disease may still be controlled and the pathogen contained. Although this disease doesn’t look like much on rhododendron or lilac, its ability to spread to oaks and kill them is what makes it so devastating. These shrubs play a key role in the spread of P. ramorum, acting as a breeding ground for spores (inoculum) that can spread through water, wind-driven rain, plant material, or human activity. Oaks are considered terminal hosts, since the pathogen does not readily spread from intact bark cankers; they become infected only when exposed to spores produced on the leaves and twigs of neighboring plants.

For full article and photos view: Purdue Landscape Report

Other resources:

Sudden Oak Death, California Oak Mortality Task Force

Sudden Oak Death, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

White Oak, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Planting Forest Trees and Shrubs in Indiana, The Education Store

Successful Oak and Hickory Regeneration, The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment: 2006-2016, The Education Store

Find a Certified Arborist, International Society of Arboriculture

Janna Beckerman, Professor

Purdue Botany and Plant Pathology

Recent Posts

- Alert – Water Your Trees, Watch Video

Posted: June 20, 2025 in Alert, Drought, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - IN DNR Deer Updates – Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Detected in Several Areas in Indiana

Posted: October 16, 2024 in Alert, Disease, Forestry, How To, Wildlife, Woodlands - 2024 Turkey Brood Count Wants your Observations – MyDNR

Posted: June 28, 2024 in Alert, Community Development, Wildlife - Spongy Moth in Spring Time – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: June 3, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - MyDNR – First positive case of chronic wasting disease in Indiana

Posted: April 29, 2024 in Alert, Disease, How To, Safety, Wildlife - Report Spotted Lanternfly – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 10, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Invasive Insects, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Declining Pines of the White Variety – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: in Alert, Disease, Forestry, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Are you seeing nests of our state endangered swan? – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 9, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, How To, Wildlife - 2024-25 Fishing Guide now available – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 4, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, How To, Ponds, Wildlife - Look Out for Invasive Carp in Your Bait Bucket – Wild Bulletin

Posted: March 31, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Invasive Animal Species, Wildlife

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands