Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: Indiana DNR has confirmed the state’s first positive case of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in LaGrange County. CWD is a fatal infectious disease, caused by a misfolded prion, that affects the nervous system in white-tailed deer. It can spread from deer-to-deer contact, bodily fluids, or through contaminated environments.

There have been no reported cases of CWD infection in people, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that hunters strongly consider having deer tested before eating the meat. The CDC also recommends not eating meat from an animal that tests positive for CWD.

CWD has been detected in 33 states including the four bordering Indiana (Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and Kentucky). Because CWD had been detected in Michigan near the Indiana border, a detection in LaGrange County was likely.

If you see any sick or dead wildlife, deer or otherwise, please report your observations on the DNR: Sick or Dead Wildlife Reporting page.

For more information visit DNR: Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD).

To subscribe to the newsletter visit MyDNR Email Newsletter.

Resources:

Chronic Wasting Disease, USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Hunting & Trapping, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife , The Education Store

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Trail Camera Tips and Tricks, Got Nature? Blog

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Ask the Expert: Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment – Birds and Salamander Research, Purdue Extension – FNR

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Deer Impact Toolbox, Got Nature? blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: Hoosiers are in for a special treat this spring. If you have lived in Indiana for more than a year, you have probably grown accustomed to the singing of cicadas in the later days of summer. However, in some years, cicadas will emerge in the spring. This occurred in 2021 when most of the state was inundated in periodical cicadas as Brood X emerged from their 17-year development. This year, two broods will emerge concurrently: Brood XIII and Brood XIX. Brood XIII is a 17-year cicada, while Brood XIX is a 13-year cicada. The emergence of these two broods isn’t unusual, but this year is special because they will asemerge at the same time. Their schedules haven’t aligned for over two hundred years! The last time these two cicada songs were heard together, Thomas Jefferson was in the White House. While this may sound like Indiana is about to be covered in cicadas, there are a few facts that may change your expectations.

There are two types of cicadas in the Midwest: annual cicadas and periodical cicadas. Annual cicadas, as the name implies, are seen each year. They normally spend two to five years underground, but there are enough of them that we see them emerge each year. Annual cicadas emerge individually, not as a group, and we see them towards the end of the summer, thus their other common name, “dog day cicadas”. Periodical cicadas have a much different life cycle. They remain in the ground as nymphs for either thirteen or seventeen years, feeding on the roots of the trees they will eventually climb. Around April, the broods will emerge together using a combination of temperature and their own internal clock. Both types of cicadas feed on deciduous trees and tend to inhabit areas where eggs were laid during previous emergences, giving them a low likelihood of moving to new areas. Annual cicadas are green with black eyes, and periodical cicadas have dark-colored bodies with red eyes and orange legs, making it easy to differentiate them as we enter the early summer and both types are present.

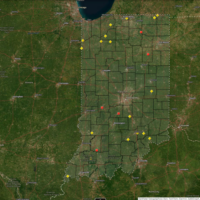

The term “brood” cicada biology is referring to a group of cicadas that share the same developmental time and the same physical area. A brood will often contain several different species, though they will all belong to the genus Magicicada. Cicadas in a brood do not need to be genetically related to each other. Some broods are very small and cover a small area, whereas others can cover a significant portion of the Midwest. For example, Brood XII, a brood of 17-year cicadas, last appeared in 2023 and has only been detected in Allen and Orange counties. On the other hand, Brood X, also known as the Great Eastern Brood, covers the entirety of Indiana and several other states. Brood XIII and Brood XIX both cover several states, but they will have very little overlap in Indiana. Only eight western counties, between Posey and Jasper counties, will experience Brood XIX, and three northern counties (Lake, LaPorte, and Porter) will see Brood XIII. Nowhere in Indiana do the broods overlap. Essentially, while there will be a lot of cicadas emerging all at once, the lack of overlap will mean this emergence will be notable, but nothing compared to the Brood X emergence a few years ago.

To view this full article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

Periodical Cicadas, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Entomology

Billions of Cicadas Are Coming This Spring; What Does That Mean for Wildlife?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

17 Ways to Make the Most of the 17-year Cicada Emergence, Purdue College of Agriculture

Ask an Expert: Cicada Emergence Video, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-FNR

Periodical Cicada in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Cicada Killers, The Education Store

Purdue Cicada Tracker, Purdue Extension-Master Gardener Program

Cicada, Youth and Entomology, Purdue Extension

Indiana Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

Alicia Kelley, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Coordinator

Purdue Extension – Entomology

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Specialist

Purdue Extension – Entomology

White-tailed deer are an important part of our Hoosier natural areas and a true conservation success story. Once extirpated from Indiana, deer now thrive in all 92 counties.

Deer can significantly impact the make-up of plants in our natural areas through the plants they eat (referred to as browsing). When the number of deer on the landscape is in balance with the available habitat and deer browsing is at a low intensity, deer can positively impact our forests’ plant diversity. When deer are overabundant, their browsing can impact forests in a variety of negative ways.

5 Steps to address deer impacts to Indiana Woodlands:

Understanding

Understand how deer impact Indiana’s forest ecosystems.

Identify

Identify signs and symptoms of deer impact in your woodland.

Monitor

Monitor how deer are impacting your woodland over time.

Manage

Decide how to manage deer and their impact on your woodland.

Evaluate

Evaluate if the management actions you took reduced deer impact on your woodland.

Check out the new Deer Impact Toolbox website for publications and more details to discover the steps landowners and land managers can take to understand, monitoring, and manage deer impacts to Indiana’s forests.

Don’t miss the videos: Monitoring Deer Impacts on Indiana Forests: Ten-Tallest Method and Monitoring Deer Impacts on Indiana Forests: Accessing Vegetation Impacts for Deer (AVID) Plots.

Check out the College of Agriculture news article to learn more: Deer Impact Toolbox provides guidance for Indiana forest landowners and managers.

Resources:

Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Understanding White-tailed Deer and Their Impact on Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Monitoring White-tailed Deer and Their Impact on Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Managing White-tailed Deer Impacts on Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Deer Harvest Data Collection, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

Handling Harvested Deer Ask an Expert? video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: Researchers at Purdue University are studying the willingness of hunters and nonhunters to help reduce the spread of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in white-tailed deer. CWD is a fatal neurological disease affecting deer and is caused by an infective protein (prion) that damages the animal’s nervous system. CWD is contagious to deer and can spread through deer-to-deer contact or through contaminated environments. To date, CWD has not been detected in Indiana. No cases of CWD have been recorded in humans.

Researchers at Purdue University are seeking volunteers to participate in this research study. Information collected may help inform Indiana DNR’s response to CWD. Participants will answer online survey questions and use a web app that shows how CWD may spread. The activity and survey questions take about 30 minutes to complete. The study is open to everyone 18 years or older. All that is required to participate is a computer or tablet. Follow this link to Purdue’s website to participate in the study.

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a fatal neurological disease affecting white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, and moose. It is a member of a group of diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), or prion diseases. For more information about this disease visit Indiana Department of Natural Resources – Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD).

For questions about this study, please email the research team at cwdwebapp@purdue.edu and place in the subject line: “Web App Use and Intention to Reduce Chronic Wasting Disease Spread; Principal Investigator – Dr. Patrick Zollner; IRB Number – IRB-2023-1039″.

To get started, please visit the CWD Web App.

Resources:

Dr. Pat Zollner, Professor of Quantitative Ecology, Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife , The Education Store

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Trail Camera Tips and Tricks, Got Nature? Blog

Hunting Guide for 2023-2024, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

Ask the Expert: Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment – Birds and Salamander Research, Purdue Extension – FNR

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: As spring has sprung, so has new wildlife. It may be tempting to cuddle cute, young wildlife, but it’s important to always assess the situation from a safe distance.

Young wildlife’s best chance of survival is with their mother, and your support can often unintentionally harm wildlife if that support is not needed. If young wildlife have fallen out of a den or nest, you can return them to their home and then leave the area. It is common for a mother to leave her young for long periods of time to forage for her and her young, so don’t linger around wildlife or their homes too long. Doing this can dissuade a mother from returning or alert predators to the young.

If you’re uncertain whether wildlife need assistance, contact a wildlife rehabilitator before picking up wildlife. If wildlife truly need assistance, they must be turned over to a permitted wildlife rehabilitator within 24 hours. Find a list of permitted wildlife rehabilitators on our website.

To learn more, please visit DNR: Fish & Wildlife Resources.

To subscribe to the newsletter visit MyDNR Email Newsletter.

Resources:

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife – The Education Store

ID That Tree – YouTube Playlist

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

Ask the Expert: Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment – Birds and Salamander Research, Purdue Extension – FNR

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Creating a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan for Landowners, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Birds and Residential Window Strikes: Tips for Prevention, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Managing Woodlands for Birds Video, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Developing a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

The Nature of Teaching, YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching: Common Mammals of Indiana, The Education Store

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

WRTV, Indianapolis News and Headlines: WEST LAFAYETTE — Elizabeth Long loves bugs.

WRTV, Indianapolis News and Headlines: WEST LAFAYETTE — Elizabeth Long loves bugs.

And she wants you to know that this summer is going to be huge for bug lovers, thanks to the emergence of two special broods of cicadas, which hasn’t happened in more than two centuries.

“That’s really, really exciting for these periodical cicadas, these two broods that are going to be emerging this year,” said Long, a Purdue University assistant professor of entomology.

“The big deal is the fact that they will be emerging in synchrony for the first time (since 1803). It’s a really long time.”

Long has a doctorate from the University of Missouri in plant, insect and microbial sciences and specializes in managing pests and beneficial bugs on farms and orchards.

And just how much does Long love bugs?

Well, she described the big green-and-black cicadas we see every summer in Central Indiana as “cute.”

“They’re green, they have a white belly,” she said. “I think they’re very cute. They’re very clumsy, you know.”

Long said these two broods of cicadas will be emerging in southern and northern parts of Indiana for about a month starting in May, then they’re gone.

WRTV asked Long about this summer’s ridiculously rare emergence of the 17-year Brood XIII (or Brood 13) and the 13-year Brood XIX (Brood 19) cicadas.

Question: What’s so special about the cicadas we are going to see this summer?

Long: We don’t have many insects that stay underground as immatures for this long, you know. It’s I think pretty amazing. So that’s really, really exciting for these periodical cicadas, these two broods that are going to be emerging this year. The big deal is the fact that they will be emerging in synchrony for the first time (since 1803). It’s a really long time.

The main difference between the two broods is the time that they spend (before) they emerge. So one is a 13-year brood and, it’s a little confusing because… the two broods that are going to emerge are Brood 19 (Brood XIX) and Brood 13 (Brood XIII).

Brood 19, which is just the number assigned to this group that emerges, those are 13 year cicadas… Then Brood 13, which is a little bit confusing… they emerge every 17 years.

So you can see that 13-17 overlap. That’s how we’re in that coincidence with the synchrony based on the math of them emerging both at the same time this year.

It so weird that 19 is 13 (years) and 13 is (17 years). I had to read up on it to get it straight.

WRTV: No wonder you guys have to get advanced degrees to understand bugs.

Long: Everyone thinks they’re simple… I’m like, these insects, they keep it challenging.

To see the full article, please visit WRTV Indianapolis News and Headlines.

Resources:

Periodical Cicadas, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Entomology

Billions of Cicadas Are Coming This Spring; What Does That Mean for Wildlife?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

17 Ways to Make the Most of the 17-year Cicada Emergence, Purdue College of Agriculture

Ask an Expert: Cicada Emergence Video, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-FNR

Periodical Cicada in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Cicada Killers, The Education Store

Purdue Cicada Tracker, Purdue Extension-Master Gardener Program

Cicada, Youth and Entomology, Purdue Extension

Indiana Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

Vic Ryckaert, Digital Reporter

WRTV Indianapolis

Elizabeth Y. Long, Assistant Professor

Purdue University Department of Entomology

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: A pair of barn owls have made a home in the property’s nest box, and you can watch this couple via a live webcam by going to the Goose Pond FWA camera page.

Barn owls are an endangered species in Indiana due to grassland habitat loss. Fewer than 50 nests are found annually in Indiana. To provide barn owls with secure nesting sites that are protected from predators, the DNR has built more than 400 nest boxes and erected them in barns and other structures with suitable habitat during the last 30 years.

The barn owl nest box at Goose Pond FWA was completed in March 2022 and is located next to its Visitors Center. This is the first nesting pair that has decided to call it home. The Friends of Goose Pond group helped provide funding for the camera and box, which has marine-grade plywood to keep the residents dry. It was painted the same color as the Visitors Center and looks like a house.

To learn more please visit the DNR Calendar.

Sign up to receive the MyDNR Newsletter by email: MyDNR Email Newsletter

Resources:

Barn Owl, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Barn Owl Nest Webcam, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Creating a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan for Landowners, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Climate + Birds, Purdue Institute for Sustainable Future

Birds and Residential Window Strikes: Tips for Prevention, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Breeding Birds and Forest Management: the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment and the Central Hardwoods Region, The Education Store

Managing Woodlands for Birds Video, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Developing a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

The Nature of Teaching, YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching: Common Mammals of Indiana, The Education Store

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

For first time in 221 years, two cicada broods to emerge in Indiana simultaneously, The Indianapolis Star: Cicadas are buzzing back to Indiana in 2024, and in a big way say bug experts.

For first time in 221 years, two cicada broods to emerge in Indiana simultaneously, The Indianapolis Star: Cicadas are buzzing back to Indiana in 2024, and in a big way say bug experts.

For the first time in 221 years, two different broods of cicadas — the 17-year Brood XIII and the 13-year Brood XIX — will appear in parts of Indiana and other states. A dual emergence is rare, according to Dr. Gene Kritsky of Cincinnati’s Mount St. Joseph University.

The last time two broods of cicadas emerged at once in Indiana, the year was 1803 and Thomas Jefferson was President. Different broods of cicadas have popped up in other states, however, such as Missouri in 1998, or when rock album “Windows from Heaven” was released by Jefferson Starship.

Here’s what we know about this unique, natural event happening in Indiana and large swaths of the Midwest.

How often do cicadas appear in Indiana?

While annual cicadas appear every 2-5 years, broods of periodical cicadas will emerge once every 17 years across the Hoosier state. There are two broods, however, that emerge every 13 years, according to Purdue University.

These black-bodied, red-eyed, winged insects crawl out of the ground from around late May to June to reproduce and begin their life-cycle anew. Cicadas can be found on every continent except Antarctica. There are more than 3,000 different species of cicadas around the world, according to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

Brood XIII (17-year brood) cicadas are coming to the Midwest in 2024

Brood XIII cicadas will emerge in parts of Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin and possibly Michigan, according to CicadaMania.org, but are expected to be concentrated in Illinois. These cicadas last emerged in 2007.

This year, cicadas in Illinois will create some unique challenges for entomologists, according to the University of Connecticut. The Prairie State is home to both the 17- and 13-year cicada broods.

Where will Brood XIII cicadas appear in Indiana in 2024?

In 2024, Brood XIII cicadas will appear in areas of Lake, LaPorte, and Porter counties in the upper northwestern side of Indiana, according to Purdue University.

Do cicadas bite?

Cicadas might look scary with their red eyes, huge wings and prickly feet, but they’re harmless to humans.

They don’t sting or carry diseases, and they don’t bite. In fact, cicadas don’t have mouth parts that can bite, said Elizabeth Barnes, an entomologist with Purdue University in a previous article by IndyStar.

No, they won’t bite: Debunking 8 common myths about cicadas

What about the other species of cicadas? Where will Brood XIX (13-year brood) cicadas appear?

This year the Brood XIX cicadas are set to emerge in 15 states across the country. They’ll appear in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Virginia.

Where will Brood XIX cicadas appear in Indiana in 2024?

In 2024, the 13-year Brood XIX cicadas will appear in 8 western counties across the Hoosier State, according to Purdue University, from Posey and Warrick counties near Evansville in the south, to Newton and Jasper counties on the north.

To see the full story and video please visit the IndyStar.

Resources:

Periodical Cicadas, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Entomology

Billions of Cicadas Are Coming This Spring; What Does That Mean for Wildlife?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

17 Ways to Make the Most of the 17-year Cicada Emergence, Purdue College of Agriculture

Ask an Expert: Cicada Emergence Video, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-FNR

Periodical Cicada in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Cicada Killers, The Education Store

Purdue Cicada Tracker, Purdue Extension-Master Gardener Program

Cicada, Youth and Entomology, Purdue Extension

Indiana Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

Tim Gibb, Insect Diagnostician and Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Entomology

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: Did you know that wild game shot with lead ammunition can sometimes contain lead fragments all the way to the dinner table? Adopting different shot placement and butchering techniques can help alleviate the problem.

When shooting: Avoid shooting animals in heavily boned areas, such as the front shoulders, as this is more likely to cause bullet fragmentation. Instead, shoot animals in softer tissue, such as around the heart and lungs, to decrease fragmentation.

When butchering: Carefully observe the wound channel in the animal and generously trim away any meat that shows bullet trauma. This will help keep fragments out of your finished meat product. Properly dispose of your trimmed meat by sending it to the local landfill or burying it on private property.

Looking for another way for you and your family to avoid ingesting lead fragments? Talk to your local retailer about finding a nontoxic ammunition that’s right for you.

To learn more please visit DNR: Effects of lead on wildlife.

Resources:

Hunting Guide for 2023-2024, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Help With Wild Turkey Populations, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Turkey Brood Reporting, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Wild Turkey, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Wild Turkey Hunting Biology and Management, Indian Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources YouTube Channel, Wildlife Playlist

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Wild Bulletin, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Fish and Wildlife: In 2023, we saw wildlife wins for many rare and endangered species. We found a very young hellbender salamander in the Blue River and increased public awareness and interest in bat conservation. We discovered the banded pygmy sunfish at Twin Swamps Nature Preserve and doubled the number of active barn owl nests from five years ago.

These wildlife wins would not have been possible without those who support the Nongame Wildlife Fund. To all of you who help care for Indiana’s rare and endangered wildlife, thank you!

If you’d like to make a positive impact on Indiana’s wildlife, consider getting involved today. Subscribe to the Indiana DNR Division of Fish & Wildlife Newsletter, IN Fish & Wildlife Instagram, and IN Fish & Wildlife Facebook to stay up to date with the IN DNR-Division of Fish & Wildlife’s latest wildlife wins. Make a volunteer profile and learn more about how to become a DNR volunteer, or make a donation to the Nongame Wildlife Fund. For every $50 given to the Nongame Wildlife Fund, an additional $43 is unlocked in federal funding, making every dollar you donate go even further for Indiana’s wildlife.

To learn more please visit DNR: Nongame and Endangered Wildlife.

Resources:

Researchers Discover Young Hellbender in Blue River, Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources News & Stories

Help the Hellbender, North America’s Giant Salamander, The Education Store

Help the Hellbender website

Help the Hellbender Facebook page

Barn Owl, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Bats in Indiana, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN DNR)

Bat Houses, Bat Conservation International

Creating a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan for Landowners, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Ask an Expert: Turtles and Snakes, video

Ask an Expert: Managing Your Property for Fish and Wildlife, video

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, publication

Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots and Native Grass and Forb Plantings, video

Connecting Youth to Wildlife Webinar

Developing a Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- MyDNR – First positive case of chronic wasting disease in Indiana

Posted: April 29, 2024 in Alert, Disease, How To, Safety, Wildlife - Cicadas in Spring! – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 9, 2024 in Forestry, Plants, Safety, Wildlife - New Deer Impact Toolbox

Posted: April 7, 2024 in Forestry, Land Use, Plants, Publication, Safety, Wildlife, Woodlands - Help Research Chronic Wasting Disease – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 3, 2024 in Disease, Forestry, How To, Safety, Wildlife, Woodlands - How to Interact with Young Wildlife This Spring, MyDNR

Posted: March 28, 2024 in Forestry, How To, Safety, Wildlife, Woodlands - Rare Cicada Emergence: Q&A with Purdue Bug Expert

Posted: March 25, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Plants, Safety, Wildlife - Barn Owls in Goose Pond Fish & Wildlife Area Nest Box, MyDNR

Posted: March 4, 2024 in Forestry, Land Use, Safety, Wildlife, Woodlands - Cicadas Are Making a Rare Appearance in Indiana in 2024, Indy Star

Posted: January 20, 2024 in Forestry, Plants, Safety, Wildlife - Learn About Lead: Avoiding Lead Ingestion in Wild Game, Wild Bulletin

Posted: December 8, 2023 in Alert, Disease, How To, Safety, Wildlife - Wildlife Wins of 2023, Wild Bulletin

Posted: in Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, How To, Safety, Wildlife

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands