Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Landscape Report: It’s that time of year when we remind everyone to watch for spotted lanternfly (SLF) infestations. Spotted lanternfly is an invasive insect first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014, and has since spread throughout the eastern USA. Its preferred host is the invasive Tree-of-Heaven, but it also feeds on a wide range of important plant species, including grapes, walnuts, maples, and willows.

There are two known populations of SLF in Indiana. The first population was found in 2021 in Switzerland County, and the second population was found in Huntington County in 2022. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR), Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology, has launched a delimiting survey throughout the two counties to delimit its range and monitor for activity.

Egg hatch was confirmed in Huntington County and Switzerland County in mid-May at the two known sites. A few adults have been caught about one mile south of the core infestation site in Huntington; however, there are not any new infestations reported as of July 2023. IDNR employees have completed several egg scraping events at the infestation sites, removing over 16,800 egg masses so far this year. That’s over 672,000 eggs!

Finding this invasive insect early is crucial to preventing its spread as long as possible. Currently, SLF nymphs are in their 1st-3rd instar, so watch for small, black, white-spotted bugs on Tree-of-Heaven. Later instars are black and red with white spots. The adults are about 1 inch long, with very brightly colored wings. The forewings are light brown with black spots, and the underwings are a striking red and black, with white band in between the red and black. When at rest, the adult SLFs appear light pinkish-grey.

Report any suspect findings at https://ag.purdue.edu/reportinvasive/

To view this full article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

The Purdue Landscape Report

Spotted Lanternfly, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Entomology

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Report Invasive, Purdue College of Agriculture – Entomology

Alicia Kelley, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Coordinator

Purdue Extension – Entomology

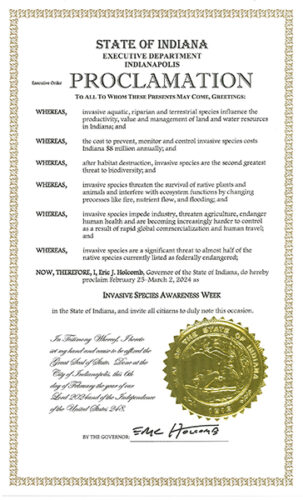

Governor Eric Holcomb has proclaimed February 25th to March 2nd as 2024 Invasive Species Awareness Week in Indiana.

Governor Eric Holcomb has proclaimed February 25th to March 2nd as 2024 Invasive Species Awareness Week in Indiana.

This serves as an important reminder for Hoosiers to be aware and report potentially devastating invasives.

This proclamation states “invasive aquatic, riparian and terrestrial species influence the productivity, value and management of land and water resources in Indiana and the cost to prevent, monitor and control invasive species costs Indiana millions annually and after habitat destruction, invasive species are a great threat to biodiversity and threaten the survival of native plants and animals and interfere with ecosystem functions by changing processes like fire, nutrient flow and flooding”.

It continues with “invasive species impede industry, threaten agriculture, endanger human health and are becoming increasingly harder to control as a result of rapid global commercialization and human travel; and invasive species are as significant threat to almost half of the native species currently listed as federally endangered.”

As Invasive Species Awareness Week starts Sunday, February 25th, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN DNR), Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources and the Indiana Invasive Species Council will answer any questions you may have.

For Questions:

Ask an Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Invasive Species – Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Indiana Invasive Species Council – Includes: IDNR, Purdue Department of Entomology and Professional Partners

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report and Learn More About Invasive Species –

Great Lakes Early Detection Network App (GLEDN) – The Center for Invasive Species & Ecosystem Health

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System

Purdue University Report Invasive Species, College of Agriculture

Check Out Our Invasive Species Videos –

Subscribe: Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Invasive Species YouTube Video Playlist includes:

- Asian Bush Honeysuckle

- Burning Bush

- Callery Pear

- Multiflora Rose

- Invasive Plants Threaten Our Forests Part 1: Invasive Plant Species Identification

- Invasive Plants Threaten Our Forests Part 2: Control and Management

More Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Video Series –

Woodland Management Moment:

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners:

ID That Tree:

More Resources –

FNR Extension Publications, The Education Store:

- Invasive Plant Species: Tree of Heaven

- Invasive Plant Species: Oriental Bittersweet

- Invasive Plant Species: Wintercreeper

- Japanese Chaff Flower

- Kudzu in Indiana

- Mile-a-minute Vine

Purdue Landscape Report:

FNR Extension Got Nature? Blog:

Don’t Miss These Resources:

Episode 11 – Exploring the challenges of Invasive Species, Habitat University-Natural Resource University

What Are Invasive Species and Why Should I Care?, Purdue Extension-FNR Got Nature? Blog

Emerald Ash Borer Information Network, Purdue University and Partners

Aquatic Invasive Species, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: A new invasive insect of concern has been identified in the state of Georgia. In August of 2023, Georgia’s Department of Agriculture, along with the USDA, confirmed the presence of the yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina, outside of the city of Savannah. To date, this is the only confirmed identification of this insect in the United States; it has already established in Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia outside of its native range. V. velutina is a native of the subtropical and tropical regions of southeast Asia, and it is not yet clear how it arrived in North America. Much like the northern giant hornet, previously known as the Asian giant hornet or ‘murder hornet’, this insect will attack honeybee hives in search of food and represents a potential danger to the beekeeping industry.

Figure 1. Yellow-Leg Hornet. Image Credit: Allan Smith-Pardo, Invasive Hornets, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

Yellow-legged hornets are predators and will regularly attack honeybees to provide food for their young, though it is possible they could attack other, similar species. Since honeybees concentrate their numbers in hives with a lot of in-and-out traffic, they provide an excellent opportunity for the hornets to hunt and provide food for their young. The hornets are effectively ambush predators, waiting in front of hive entrances and capturing workers with their legs as they leave the hive. The hornets then dismember the bees, returning to their young with only the thorax, which contains the largest amount of protein. However, it is believed that yellow-legged hornets only represent a lethal threat to weaker hives that are already experiencing problems; it is also too early to tell how already-existing honeybee issues, such as mite and disease issues, will interact with the presence of this insect.

The yellow-legged hornet, much like other members of Order Hymenoptera, is a social insect. They create oval or egg-shaped nests in trees that can house as many as 6,000 individuals. Colonies are composed of a foundress and her young, who become the workers within the colony. Female hornets will overwinter within tree hollows, leaf litter, or other environmentally stable locations, and once spring arrives, they start their own colony and give birth to new workers who care for young and hunt.

As with any new invasive species, it is critical to successful identify it and differentiate it from other species of wasps and hornets that we experience in the Midwest. At a glance, the yellow-legged hornet is barely discernable from European hornets, yellowjackets, and similar insects; they possess aerodynamic shapes with heavy yellow and black color patterns like many of their cousins. The most easily identified trait is their namesake: the legs of this insect tend to be black closer to the body, with the lower half of the leg bright yellow. The segments of the abdomen follow a similar pattern, with those segments closer to the center of the body being dominated by black, steadily becoming more yellow as you reach the tip of the abdomen. The yellow-legged hornet is also approximately an inch in length, with reproductive individuals sometimes reaching an inch and a half.

While remaining observant will be critical to reporting any invasive species, there are a few things to keep in mind about the yellow-legged hornet. This insect has only been found in one location in Georgia; no other states have any sightings or confirmed reports of this insect. There is also no evidence the insect has established a population in Georgia, there is only one confirmed sighting. The best course of action for now is to be vigilant and report any potential sightings by calling 1-866-NOEXOTIC, or you can contact our local Purdue Extension educator for assistance.

To view this full article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Pest Management, The Education Store

Protecting Pollinators: Why Should We Care About Pollinators?, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Ask The Expert: What’s Buzzing or Not Buzzing About Pollinators , Purdue Extension – Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Purdue Pollinator Protection publication series, Purdue Extension Entomology

Subscribe Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

Tom Creswell, Plant & Pest Diagnostic Laboratory Director

Purdue Botany and Plant Pathology

Cliff Sadof, Professor, Ornamental, Pest Management

Purdue Entomology Extension Coordinator

Purdue Landscape Report: The emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planennis, is still one of the most damaging insect pests ever to invade North American forests. Unlike most native boring insects, this beetle can attack and kill relatively healthy ash trees. In Indiana cities we found this insect capable of killing most of the unprotected ash trees within 6 to 10 years. Nearly 20 years after its first detection in Indiana (2004), trees still need to be protected to keep them alive. The benefits of these living ash trees easily justify the cost of monitoring them. We provide answers to common questions people have about the need for continued treatment.

- I have had a tree care specialist treat my ash trees for the last 10 years. What will happen to these trees if I stop this service? If your trees are still healthy, they were probably treated with injections of emamectin benzoate. Initially we recommended treating trees once every 2 years. This was especially helpful during the initial invasion when each newly infested tree was producing hundreds of beetles per year. Now that most of the untreated ash trees are dead in Indiana, there are fewer emerald ash borers to attack the surviving ash trees. Research clearly shows that treating trees once every 3 years is enough to keep ash trees alive. Increasing the time between treatments beyond 3 years will increase the risk of losing your trees.

We recently completed a 10-year study in Indianapolis, where large ash trees were treated at 3-year intervals (2013 and 2016), Although they were well-protected through 2019, we saw a slight increase in damage 4 and 5 years after the last injection (2020 and 2021). By the 6th year trees after the last treatment (2022), trees declined to the point that they were a safety hazard. Overall, spring treatments were more effective than fall treatments.

- Is it worthwhile to continue treating my trees? The simple answer is YES, especially if you think about the costs of the alternatives over time. Consider the following choices:

- Homeowner tree removal vs treatment. Suppose you had ash tree that was whose trunk diameter was 30 inches. If you were to have that tree and its stump removed, the cost could easily be $1800. If an ash tree is near your house or other valuable structure special precautions need to be taken to keep limbs from causing damage. These protective measures add greatly to the labor costs and could easily double the removal costs ($3600). In contrast, to keep that tree alive, you would have to inject that tree once every three years at a cost of $300 (assuming the fee is $10/ diameter inch). In other words, the $1800 -3600 you pay to remove the trees would provide 18-36 years of enjoying your tree!

- Homeowner tree replacement vs treatment. Trees grow slowly. Most add a bit less than a half an inch per year of diameter to the trunk. So, if you add $500 on top of the removal costs to plant a new tree ($2300- $4100), the same money would provide 23 to 42 years of tree enjoyment. Moreover, the tree you planted would only be half the size of the original ash tree in 30 years.

For the full article please visit Purdue Landscape Report: Should ash trees still be protected from emerald ash borer?

Resources:

New Hope for Fighting Ash Borer, Got Nature? Purdue Extension-FNR

Invasive Pest Species: Tools for Staging and Managing EAB in the Urban Forest, Got Nature?

Emerald Ash Borer, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Emerald Ash Borer Cost Calculator – Purdue Extension Entomology

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Indiana Invasive Plant List, Indiana Invasive Species Council, Purdue Entomology

Landscape Report Shares Importance of Soil Testing, Purdue FNR Extension

Find an Arborist website, Trees are Good, International Society of Arboriculture (ISA)

Tree Risk Management – The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

Cliff Sadof, Professor, Ornamental, Pest Management

Purdue Entomology Extension Coordinator

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: During the spring and summer please let us know if you think you may have seen spotted lanternfly by contacting us at 866-NO-EXOTIC (866-663-9684), or by email at DEPP@dnr.IN.gov. Please be sure to provide your contact information and detailed information about the location. Early detection is crucial to successful spotted lanternfly management efforts.

Spotted lanternfly is a major pest of concern across most of the United States. This insect is native to China and parts of India, Vietnam, Japan, and Taiwan. It was first identified as an invasive species in 2004 in South Korea and is now a major pest there. Spotted lanternfly was first detected in the United States in Pennsylvania in 2014.

In July 2021, a population of spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) was identified in Indiana in Switzerland County, near the Ohio River. A second population was found in Huntington, Indiana in July 2022. DEPP and USDA continue to conduct surveys to ascertain the extent and source of these infestations as well as determine what management strategies will be implemented.

Newsletter can be found online: MyDNR Email Newsletter

For more information please visit Spotted Lanterfly – MyDNR

Resources:

Spotted Lanternfly, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Entomology

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Report Invasive, Purdue College of Agriculture – Entomology

Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Department of Fish & Wildlife

Purdue Landscape Report: Asian jumping worms, a group of invasive earthworms, have gained a significant amount of media attention in the last several weeks, and for good reason. Unlike the nightcrawlers and other earthworms we know, Asian jumping worms do not improve soil health to the benefit of plants. Instead, jumping worms (also called crazy worms, snake worms, or ‘Alabama jumpers’) almost completely strip nutrients out of soil, altering the soil structure and severely impairing the ability to develop many kinds of plants. After they are done with an area, Asian jumping worms leave behind soil that has a texture similar to that of coffee grounds and very low nutritional value. On top of this, Asian jumping worms are capable of reproducing asexually, allowing their population to grow very rapidly and making them an invasive species of some concern.

Identification

The good news is that Asian jumping worms are not well-suited to Indiana’s environment. They aren’t capable of surviving winters in any life stage except as an egg, meaning their activity periods are limited to late June to the first hard frost of the year. If you see worms outside of this period, it’s highly unlikely an Asian jumping worm. There are also a few traits the worms have that you can use to visually confirm their identity. First off, Asian jumping worms are accurately named; when handled, they writhe and thrash similar to snakes, setting them apart from common earthworms and nightcrawlers. Jumping worms also tend to have drier skin that has an almost iridescent appearance, as compared to the slimy, moist texture of the beneficial earthworms we need for good soil health. The most consistent feature is an organ known as the clitellum, or the reproductive organs of worms. On common earthworms, this looks like a saddle-shape that partially covers several segments, is normally reddish-brown, and is raised off the surface of the body. On an Asian jumping worm, however, the clitellum is indistinguishable from other segments, save for their pale, milky color.

To view this article and other Purdue Landscape Report articles, please visit Purdue Landscape Report.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

The Purdue Landscape Report

Purdue Landscape Report Facebook Page

Gardeners Asked to be Vigilant This Spring for Invasive Jumping Worm, Purdue Extension – FNR Got Nature? Blog

Fall webworms: Should you manage them?, Purdue Landscape Report

Mimosa Webworm, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Sod Webworms, Turf Science at Purdue University

Bagworm caterpillars are out feeding, be ready to spray your trees, Purdue Extension Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Plant Doctor App Suite, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Landscape & Oranmentals-Bagworms, The Education Store

What are invasive species and why should I care? (How to report invasives.), Purdue Extension – FNR Got Nature? Blog

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Ask An Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Specialist

Purdue Department of Entomology

While earthworms in the spring are a happy sight for gardeners, an invasive worm species is wreaking havoc for landowners and gardeners in southern Indiana.

Robert Bruner, Purdue Extension’s exotic forest pest specialist, describes jumping worms, an invasive species to North America in the genus Amynthas: “Traditionally, when we see earthworms, they are deep in the ground and a little slimy. The jumping worms are a little bit bigger, kind of dry and scaly, and tend to thrash around much like a snake does.”

While worms have a reputation as a helpful species found in the soil ecosystem, invasive jumping worms do not live up to that standard, Bruner explained. Jumping worms will consume all organic material from the top layer of soil, leaving behind a coffee ground-like waste with no nutrients for plants or seeds.

Since jumping worms stay within the first few inches of topsoil, they are not creating channels for water and air the way earthworms do, disrupting water flow to plant roots.

“So basically, they’re just very nasty pests that ruin the quality of our soil, and the only thing that can really grow in soil like that are essentially invasive plants, or species that are meant to survive really harsh conditions,” Bruner said.

Currently, the worms are being found in cities around southern Indiana, he said, particularly in Terre Haute. There is still much to learn about jumping worms, making eradication efforts difficult. One thing that is known, Bruner said, is they aren’t a migrating species.

“This is the kind of invasive pest that is moved almost entirely through human activity. They don’t crawl superfast,” he explained. “So, when they move, that means they’re moving because we’re transferring soil, say, from someone’s plants or someone’s compost and we’re bringing them to a new area.”

Any invasive species sightings should be reported to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources at depp@dnr.in.gov or by calling 1-866-663-9684.

For full article with additional photos view: Gardeners asked to be vigilant this spring for invasive jumping worms, Purdue College of Agriculture News.

Other Resources:

Fall webworms: Should you manage them?, Purdue Landscape Report

Mimosa Webworm, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Sod Webworms, Turf Science at Purdue University

Bagworm caterpillars are out feeding, be ready to spray your trees, Purdue Extension Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Plant Doctor App Suite, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Landscape & Oranmentals-Bagworms, The Education Store

What are invasive species and why should I care? (How to report invasives.), Purdue Extension – FNR Got Nature? Blog

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

The GLEDN Phone App – Great Lakes Early Detection Network

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Ask An Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources

Jillian Ellison, Agricultural Communication

Purdue College of Agriculture

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Department of Entomology

Tree-of-heaven is native to Asia but has been widely planted in North America and now spreads naturally as a serious invasive tree threat.

In this episode of ID That Tree, Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee identifies the invasive tree of heaven, also known as stinking sumac, due to the foul odor that permeates from nearly all parts of the tree. The alternately held compound leaves have teeth at the base of the leaflets on stout stems, while the bark is a medium gray with white wormy marks. This tree spreads through the seeds of its female trees and from suckers off its root system, and it is also the preferred host of an invasive insect, spotted lanternfly, now found in Indiana. Learning to recognize invasive pests a good first step to limiting their spread.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel (Invasive White Mulberry, Siberian Elm, Tree of Heaven)

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Asian Bush Honeysuckle, Burning Bush, Callery Pear, Multiflora rose)

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Against Invasives, Garlic Mustard, Autumn Olive)

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Common Buckthorn, Japanese Barberry)

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

The GLEDN Phone App – Great Lakes Early Detection Network

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (Report Invasives)

How long do seeds of the invasive tree, Ailanthus altissima remain viable? (Invasive Tree of Heaven), USDA Forest Service

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Aquatic Invasive Species, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Episode 11 – Exploring the challenges of Invasive Species, Habitat University-Natural Resource University

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Spotted Lanternfly Feeds on Over 70 Plus Plant Species, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center

Purdue Department of Forestry & Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report, Why are the Japanese beetles running late this year?: Nothing heralds summer like the hum of Japanese beetles ravenously descending on a flower garden. Cool weather this spring has slowed emergence of adults from the soil. Heavy spring rains early followed by relatively drier weather in late June, may have trapped adult Japanese beetles under a crusty layer of hardened soil. Due to their large numbers in many parts of Indiana last year, they are very likely just waiting for a good rain to soften the surface, so they can dig themselves into the light of day and on to your flowers. So, if we get a little more rain by the time this article comes out, we are likely to be awash in adult beetles.

Weather is only part of what makes Japanese beetles predictably unpredictable. Beneficial organisms including fungi, microsporidia, and parasitic wasps also act different life stages of Japanese beetles. Japanese beetles have been the target of several national programs to release these beneficial organisms to reduce beetle populations. Favorable conditions for these beneficials can help reduce the local abundance of grubs and beetles.

Weather is only part of what makes Japanese beetles predictably unpredictable. Beneficial organisms including fungi, microsporidia, and parasitic wasps also act different life stages of Japanese beetles. Japanese beetles have been the target of several national programs to release these beneficial organisms to reduce beetle populations. Favorable conditions for these beneficials can help reduce the local abundance of grubs and beetles.

Although killing grubs will reduce the number of beetles, the small size of lawns and the long flight range of makes it unlikely for your grub control program to reduce defoliation. In experiments conducted in my lab over 20 years ago, we found adult beetles can easily fly a kilometer (0.66 miles) in a single day. With adults living for several weeks, it is easy to image beetles traveling long distances from untreated lawns to plants on your property.

Life cycle of Japanese beetles: As the weather warms in the spring larvae (aka white grubs) move closer to the surface and begin feeding on turf roots. In May they enter a pupal stage and stop feeding. In June they typically emerge from the soil as adults. Adults fly in summer when they feed on flowers and leaves. In late July and early August adults lay eggs into the turfgrass. White grubs hatch from eggs and feed on the roots until frost when the larvae begin dig deeper into the soil to avoid killing temperatures.

To find out what you can do about Japanese beetles and view photos view: Why are the Japanese beetles running late this year?

Resources:

Report Invasive

Invasive Insects, Got Nature?

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Indiana Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

Spotted lanternfly: Everything You Need to Know in 30 Minutes, Video, Emerald Ash Borer University

Emerald Ash Borer, EAB Information Network

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Pest Management, The Education Store

Cliff Sadof, Professor Entomology/Extension Fellow

Purdue Entomology

Spotted lanternfly is a major pest of concern across most of the United States. Spotted lanternfly (SLF) is an invasive planthopper native to China that was first detected in the United States in Pennsylvania in 2014. SLF feeds on over 70+ plant species including fruit, ornamental and woody trees with tree-of-heaven as its preferred host. Spotted lanternfly is a hitchhiker and can easily be moved long distances through human assisted movement.

Spotted lanternfly is a major pest of concern across most of the United States. Spotted lanternfly (SLF) is an invasive planthopper native to China that was first detected in the United States in Pennsylvania in 2014. SLF feeds on over 70+ plant species including fruit, ornamental and woody trees with tree-of-heaven as its preferred host. Spotted lanternfly is a hitchhiker and can easily be moved long distances through human assisted movement.

Tree of heaven (TOH) is the preferred host for the spotted lanternfly (SLF). The ability to identify TOH will be critical to monitoring the spread of this invasive pest as the 4th-stage nymphs and adult spotted lantern-flies show a strong preference for TOH.

Report a Sighting

- Take a picture and note your location.

- If you can, collect a sample of the insect by catching it and placing it in a freezer. You can use any container available as long as it has a tight seal (like a water bottle) so that the spotted lanternfly can’t escape.

- Report the sighting at DEPP@dnr.in.gov, eddmaps.org, or 1-866-663-9684.

- Check your car and outdoor equipment for spotted lanternfly eggs, nymphs, and adults before driving or moving to a new location.

- Don’t move firewood because it can spread spotted lanternfly and many other invasive insects.

- Stay up to date with the latest spotted lanternfly information by subscribing to our newsletters (www.purduelandscapereport.org/ and www.in.gov/dnr/entomology/entomology-weekly- review/) and following us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (@reportINvasive and @INdnrinvasive).

- Share your spotted lanternfly knowledge with others!

Resources:

Spotted Lanternfly, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Entomology

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Report Invasive

Diana Evans, Extension and Web Communication Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- Report Spotted Lanternfly – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 10, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Invasive Insects, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - State of Indiana Proclamation-Invasive Species Week 2024

Posted: February 19, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Invasive Animal Species, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - New Invasive Predator of Honeybees-Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: August 27, 2023 in Alert, How To, Invasive Insects, Wildlife - Should Ash Trees Still be Protected From Emerald Ash Borer?

Posted: May 12, 2023 in Forests and Street Trees, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - Report if You See a Spotted Lanterfly – MyDNR

Posted: May 10, 2023 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Asian jumping worms: Where to get started – Landscape Report

Posted: April 27, 2023 in Invasive Insects, Nature of Teaching, Wildlife, Woodlands - Gardeners Asked to be Vigilant This Spring for Invasive Jumping Worm

Posted: March 17, 2023 in Forestry, How To, Invasive Insects, Plants, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Invasive Tree of Heaven

Posted: February 23, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Why are the Japanese beetles running late this year?

Posted: July 20, 2022 in Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Spotted Lanternfly Feeds on Over 70 Plus Plant Species

Posted: June 2, 2022 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodland Management Moment

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands