Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Extension has helped subdue invasive species ranging from kudzu and emerald ash borer to thousand canker disease and spongy moth. The work continues against new waves of invaders, such as tree of heaven and spotted lanternfly.

Aside from pushing out native species, spotted lanternfly presents an economic threat to Indiana’s forests, which annually provide $3.5 billion in value-added and $7.9 billion in value of shipments to Indiana’s economy (data from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources) and its commercial vineyards, which contribute $2.4 billion annually (data from the Indiana Wine Grape Council). Nationally, invasive species cost the U.S. an estimated $138 billion per year in damages, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Spotted lanternfly is an imminent risk to Monroe County. That’s largely because of the tree of heaven, which has established scattered populations throughout Indiana.

“The spotted lanternfly has arrived in Indiana, and the tree of heaven is its preferred food source,” says Ellen Jacquart, president of Monroe County Identify and Reduce Invasive Species. “Indeed, some recent research shows that spotted lanternflies may not be able to complete their metamorphosis into an adult if they don’t feed on the tree of heaven. So now we have this push to get rid of tree of heaven because the spotted lanternfly was just found two counties east of us.”

Jacquart has worked with Extension’s Robert Bruner, exotic forest pest specialist, and Lenny Farlee, sustaining hardwood specialist, to combat the pest and other invasives.

“Bob Bruner and his updates on spotted lanternfly have been awesome,” Jacquart says. “Lenny has become one of the highlight speakers at many of the invasive species conferences that I go to because he is so good at explaining control techniques. He brings in a lot of experience and knowledge, whether you’re working at the scale of a small yard or 40 acres.”

The Forest Pest Outreach and Survey Project (FPOSP) — a joint effort between Purdue Extension Entomology and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR) — has long addressed the growing problem of exotic pests through detection, education and reporting. FPOSP’s outreach includes educational and professional development programming. The project also seeks to create a group of citizen scientists motivated to help report and manage invasive species.

Bruner expanded this effort in 2023 by launching a series of live webinars called ReportINvasive. He also began providing in-person presentations at events such as the Indiana Green Expo, Indiana Invasive Species Conference and Cooperative Invasive Species Management Areas meetings.

The bulk of invasive plant work in forestry involves herbicide applications to control the intruders, says Philip Marshall, forest health specialist at the Indiana DNR. Extension specialists are among the speakers at the annual Forest Pesticide Training Program, which provides approved continuing education credits from the Office of the Indiana State Chemist. Extension presenters regularly share best practices and research with attendees, who often engage in invasive species management in various capacities.

“I rely on Purdue and the Extension people for technical expertise.” – Philip Marshall, forest health specialist, Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

Marshall cites the value of the training program, as well as the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab, which helps county extension educators and other Indiana stakeholders identify invasive species and other plant and pest problems. An insect, a virus, a fungus or a plant can become an invasive pest or pathogen.

Marshall, Farlee and other experts from Purdue, Indiana DNR and elsewhere spoke in September at the 2025 Indiana Invasive Species Conference. Hosted by Extension and the Indiana Invasive Species Council, the conference catered to scientists, researchers, landscapers, landowners and concerned citizens alike.

Henry Quesada, Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources program leader, delivered the keynote address. His topic: Ecological, social and economic consequences of invasive species on forests and forest products, the same reasons that drive Extension’s work forward.

To view this article along with other news and stories posted on the Purdue Extension website view: Uniting Indiana Residents Against Invasive Species.

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Episode 11 – Exploring the challenges of Invasive Species, Habitat University-Natural Resource University

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Report Spotted Lanternfly, Purdue College of Agriculture Invasive Species

Purdue Extension is proud to share the 2025 Impact Report, a showcase of the people, programs, and partnerships driving stronger, more resilient communities across Indiana. This year’s report highlights how research from Purdue’s College of Agriculture is being put into action, from addressing the spread of tar spot in corn, to monitoring invasive species, to supporting farmers navigating concerns around Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (bird flu).

Purdue Extension is proud to share the 2025 Impact Report, a showcase of the people, programs, and partnerships driving stronger, more resilient communities across Indiana. This year’s report highlights how research from Purdue’s College of Agriculture is being put into action, from addressing the spread of tar spot in corn, to monitoring invasive species, to supporting farmers navigating concerns around Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (bird flu).

Here is a quick snapshot of the great articles and information you will find:

- Saving One of Indiana’s Top Crops From Tar Spots

- 4-H Tech Changemakers Lead the Way in AI

- Teaching Small Steps to Achieve Healthier Lives

- Strengthening Financial Security Through Tax Preparation and Education

- Uniting Indiana Residents Against Invasive Species

Highlighting Lenny Farlee, Extension forester, and Henry Quesada, professor and assistant director of Extension. Check out all of our FNR resources listed below. - Supporting Childcare Providers to Create Stronger Communities

- Emergency Preparedness and Response to Highly Pathogenic Avian Flu

- Making the Best Better: Strengthening Teen Leadership Skills

- Check out program impacts

Explore the full report to see how Extension is making a difference statewide and beyond: Purdue Extension Impact Report 2025.

Resources:

What are Invasive Species and Why Should I Care?, Purdue Extension – Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Blog

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Asian Bush Honeysuckle, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Burning Bush, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Callery Pear, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Multiflora Rose, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Invasive Plants Threaten Our Forests Part 1: Invasive Plant Species Identification

Aquatic Invasive Species, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Emerald Ash Borer Information Network, Purdue University and Partners

The GLEDN Phone App – Great Lakes Early Detection Network

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System

1-866 No EXOTIC (1-866-663-9684)

depp@dnr.IN.gov – Email Indiana Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Subscribe to Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching, Purdue College of Agriculture

Community Development, Purdue Extension

Purdue Landscape Report: Spotted lanternfly (SLF) has been the subject of a lot of media attention in the last few years. In the east, states like Pennsylvania and New York have been dealing with heavy infestations since the insect was first detected in 2014. In Indiana, this invasive planthopper arrived three years ago, infesting two counties on the eastern side of the state. Since then, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources and Purdue University have been working together to mitigate the spread of this insect as well as educate Hoosiers on what they can do to help. Spotted lanternfly is still on the move, and this update will help refresh you on how this bug works, and where they are headed.

Figure 1. Upper left: early-instar SLF; upper right: late-instar SLF; bottom left: adult SLF with egg mass; bottom right: uncovered SLF eggs.

Life cycle

Spotted lanternfly is an annual insect, having only a single generation in a year under normal conditions. The insect goes through incomplete metamorphosis; immature stages, called nymphs, resemble smaller, wingless versions of the adults. Nymphs will begin to appear in April or May, developing through four instars, until they reach adulthood in late summer. With each instar, the period in between molting, the nymph will grow larger, develop wingpads, and eventually change color. Early instars are black with a white dot pattern, while later instars will be bright red with black and white patterning (Fig. 1). Late instar nymphs are often compared to milkweed bugs or lady beetles. Once they complete development in the late summer or early fall, they will mate and lay egg masses covered in a protective substance that makes them resemble mud. Eggs masses will overwinter until the spring, while adult insects will die as temperatures cool. In Indiana, depending on temperature, adults can be seen as late as early November.

Impact

Spotted lanternfly is a sap-feeding insect, using syringe-like mouthparts to drain nutrients directly from plant tissues. Like other sap-feeding insects, the activity of SLF wounds the plant, creating openings for various pathogens to exploit. Feeding by SLF has been shown to reduce overall health of their hosts, reducing their capacity to survive overwintering, and potentially kill the host plant depending on species. They also produce a sugary waste known as honeydew; while honeydew itself is not harmful, it acts as a growing substrate for sooty mold, which can have a serious impact the photosynthesis of understory foliage as well as attract other nuisance insects.

Spotted lanternfly is a generalist herbivore and can feed on over 100 different species of plant and tree in Indiana. However, this insect has shown strong preference towards certain species, often with devastating consequences. The most preferred host is tree-of-heaven, an invasive tree species in North America. Tree-of-heaven is the primary host of SLF in their shared native range, and the insect appears to experience high reproductive success on it even when they share a new environment. Grapes are also highly preferred by SLF, and infestations will typically result in overfeeding and the death of the plant. Black Walnut, American river birch, and various maple species are also at risk of severe damage from this insect. Evidence has also suggested that maple, when used for syrup production, will experience reductions in yield and quality when attack by spotted lanternfly.

Where are they now?

Spotted lanternfly has been present in Indiana since 2021, first arriving in Huntington and Switzerland Counties. In Huntington, the infestation occupies a stand of tree-of-heaven next to an industrial parking lot. Tree-of-heaven moved into the neighboring residential area, allowing SLF to also spread with it. The more rural infestation in Switzerland County was traced to a vehicle transported from Pennsylvania, and the insect has taken advantage of patches of tree-of-heaven in nearby wooded areas. While both infestations have strongly associated with the insect’s primary host, there is some evidence that SLF is beginning to take advantage of other nearby plants, such as maple. In the last year, SLF moved a significant distance and has been detected in several more counties, including Elkhart, St. Joseph, Porter, Allen, Dekalb, and Noble Counties. Most of the activity has been found on tree-of-heaven along rail lines, supporting the idea that the insect is dispersed by rail traffic moving westward out of infested areas.

It’s important to remember that trains aren’t the only vehicles that can have SLF passengers. These insects, and their egg masses, can be found on just about any surface, including the car you drive to work, the RV you used for recreation, semi-trucks that cross the country, and more. Purdue Entomology and Indiana DNR are encouraging everyone to inspect their vehicles when traveling through any of the infested areas. Also check all recreational vehicles and trailers for spotted lanternfly egg masses; if found, scrape them off into a bag or bucket filled with soapy water. This fall and winter, we also want to encourage everyone to please burn any firewood where you buy it, and please don’t move it off your property if you chop it yourself- especially if you are burning tree of heaven. Egg masses will stick to firewood and can survive our winters very well.

What can I do?

We are still learning about the spotted lanternfly’s distribution through Indiana, and we need the help of citizen scientists to effectively track the insect’s movement. If you believe you’ve seen spotted lanternfly, please report it using any of the resources listed below. You can also feel free to reach out to Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator, by emailing them at rfbruner@purdue.edu, or you can report sightings by calling 1-866-NOEXOTIC.

Original article posted: Spotted Lanternfly is on the Move!.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Spotted Lanternfly Resources:

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Indiana Woodland Steward

Spotted Lanternfly – includes map with locations, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Entomology

Report Spotted Lanternfly, Purdue College of Agriculture Invasive Species

Other Resources Available:

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Woodland Management Moment: Invasive Species Control Process, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Report Invasive, Purdue College of Agriculture – Entomology

ReportINvasive, Purdue Report Invasive Facebook posts include webinars and workshops

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

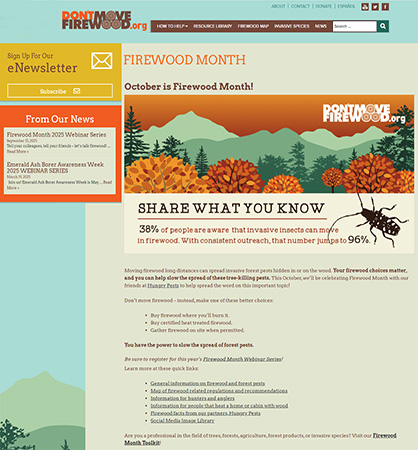

As the crisp autumn air settles in and campfires become a seasonal staple, October brings an important reminder: your firewood choices matter. That’s why October is officially Firewood Month, a nationwide campaign to raise awareness about the risks of moving firewood and the spread of invasive forest pests.

Why “Don’t Move Firewood” Matters

Why “Don’t Move Firewood” Matters

Transporting firewood, even just a few miles, can unintentionally spread destructive pests like emerald ash borer, Asian longhorned beetle and spongy moth. These invaders often hide inside or on firewood, threatening Indiana’s forests, parks and urban trees.

The Don’t Move Firewood website offers excellent resources to help you make informed choices. Whether you’re heating a cabin, heading out to hunt, or planning a backyard bonfire, they recommend:

- Buying firewood where you’ll burn it

- Choosing certified heat-treated wood

- Gathering wood on-site when permitted

You can also explore their Firewood Month Toolkit, maps of regulations and a webinar series designed for professionals and outdoor enthusiasts alike.

While October is Firewood Month, the risk of spreading invasive pests lasts well beyond the fall. Many forest pests remain a threat throughout the year. Adults may still be visible until the first hard freeze, and egg masses can be observed from now through June. The spotted lanternfly females lay egg masses in late summer through early winter, often peaking in October. These masses can survive through winter and hatch in the spring. Learn more about the Spotted Lanternfly from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. This is why it’s important to practice safe firewood habits year-round.

Spotlight on ReportINvasive

Check out the latest post on the ReportINvasive Facebook which reinforces the importance of Firewood Month. ReportINvasive is a trusted source for updates on invasive species in Indiana, and their social media outreach is a great way to stay informed and engaged. Give the Facebook page a LIKE and FOLLOW for future webinars and workshops.

Concerned About Insects? Purdue Extension Entomology Can Help

If you suspect insect damage or want to learn more about forest pests, the Purdue Extension Entomology team is an outstanding resource. Their experts provide science-based guidance on insect identification, management strategies, and outreach materials to help protect Indiana’s ecosystems.

If you suspect insect damage or want to learn more about forest pests, the Purdue Extension Entomology team is an outstanding resource. Their experts provide science-based guidance on insect identification, management strategies, and outreach materials to help protect Indiana’s ecosystems.

Let’s work together to keep Indiana’s forests healthy and resilient. This October, make the smart choice—don’t move firewood!

More Resources

Spotted Lanternfly – including map sharing locations, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

October is Firewood Awareness Month!, Purdue Landscape Report

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Aquatic Invasive Species, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Emerald Ash Borer Information Network, Purdue University and Partners

Invasive plants: impact on environment and people, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Entomology Weekly Review, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Entomology & Plant Pathology

Division of Entomology & Plant Pathology, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Diana Evans, Extension and Web Communication Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Fig. 1. Yellowing mottling damage due to scale feeding. Image: Brian Kunkel, University of Delaware.

Purdue Landscape Report: Christmas tree growers have been struggling with an invasive scale pest called Cryptomeria scale (Aspidiotus cryptomeriae), which is a serious pest of conifers. The scales infest the undersides of the needles and extract plant juices with their piercing-sucking mouthparts. Economic losses are due to the unsightly yellow discoloration and needle drop that occurs from the insect feeding (Fig. 1).

Life cycle: Cryptomeria scale has two generations per year. It overwinters as second-instar nymphs on the undersides of the needles, and in spring (March-April) the nymphs begin feeding again and continue development. They reach maturity by late spring. The adult females are flightless and remain stationary. They have a “fried egg” appearance of a white oval shape with a yellow center (Fig. 2). The adult males are alate, meaning they have wings (Fig. 3). Males fly in the summer, typically in July. They will mate with the females and die shortly after. The females lay eggs in the weeks following the mating flight. Egg hatch occurs around late August. These newly-hatched nymphs are called “crawlers”, because they are mobile and will disperse across the plant to find a new spot to settle and feed. Cryptomeria scale nymphs may not move very far from the female; many settle close to the female. The crawler stage is over by early September, when most have established a feeding site. They will develop through the fall into second-instars and overwinter until the following spring.

Management: Scout for the scale in the late winter when the scales are overwintering and prune infested branches, or remove the entire tree if heavily infested. Lady beetles and parasitic wasps will feed on Cryptomeria scale, so use biorational insecticides to maintain populations of beneficial insects which help control Cryptomeria scale and other pests.

Since Cryptomeria scales are armored scales, horticultural oils are recommended instead of insecticidal soaps for effective management (Quesada et al. 2017). Apply oils before bud break to target overwintering scales. Make sure to saturate the needles fully, especially the undersides of the needles, to smother the scales. For a more aggressive solution, dinotefuran can be applied for control of Cryptomeria scale. Basal bark applications of dinotefuran applied just after bud break were shown to significantly reduce scale populations and actually improved the rate of parasitism from parasitic wasps (Cowles 2010).

Not sure if you Cryptomeria scale or something else? Reach out to the Plant Pest and Diagnostics Lab for identification services!

View the original article on the Purdue Landscape Report website: Cryptomeria scale on Christmas trees.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

A Choose-and-Cut Pine and Fir Christmas Tree Case Study, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Living Christmas Trees For The Holidays and Beyond, The Education Store

Tips for First-Time Buyers of Real Christmas Trees, The Education Store

Growing Christmas Trees, The Education Store

Selecting an Indiana-Grown Christmas Tree, The Education Store

Winterize Your Trees, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

What do Treed Do in the Winter?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Forest/Timber Playlist, subscribe to Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Ask the Expert: Holidays in the Wild, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

ID That Tree: Balsam Fir, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

ID That Tree: Scotch Pine, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

To identify other pine trees view ID That Tree, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Purdue Plant Doctor, Purdue Extension

Purdue Extension – Entomology

Purdue Landscape Report: It’s that time again! With the arrival of warm temperatures and increased rainfall, many of us are getting to work on our lawns, gardens, and landscaping. Unfortunately, this often comes with discovering what new (or old) invasive species are here to haunt us. So far this year, the invasive I’ve gotten the most questions on is the Asian jumping worm. This earthworm’s life cycle tends to experience ‘boom & bust’ years due to their feeding habits, and, anecdotally speaking, we appear to be experiencing an increase in their populations throughout the state this season. Now is a great time to brush up on our understanding of this organism, and the revisit how it impacts our environment.

Figure 1. The clitellum, the set of pale, milky colored segments, is the reproductive organ of earthworms.

Identification

While Asian jumping worms share a lot of traits with other, less harmful earthworm species, they do have some features we can use to differentiate them from the rest. Jumping worms tend to be darker in color, since they live either on top of the soil or just under the first layer of plant detritus and get more exposure to sunlight. Asian jumping worms also have a significantly higher number of bristles, or setae, that they can use to move around. They can have as many as forty bristles per segment, in contrast to the eight found on other species, giving them the traction they need to wriggle and squirm as violently as they do. Perhaps the easiest feature we can use to identify them is the clitellum, the organ that contains they reproductive organs. On Asian jumping worms, the clitellum just looks like a very pale set of segments close to the anterior end of the worm, whereas on most other worms, it’s about midway down the body and saddle-shaped. Finally, we can detect their presence by changes in our soil. Asian jumping will not improve soil quality for growing like other earthworms can, but rather change the soil consistency into something like coffee grounds, rendering it unsuitable for growing most crops and ornamentals.

Environmental Impact

As I alluded to above, Asian jumping worms do significant damage to soil quality when left unmanaged. These earthworms, unlike their beneficial cousins, do not provide ecosystems services like soil aeration or castings that help add nutrients to the soil. Since they live at the surface, they do not burrow, and their castings lock in nutrients and often get swept away by hydrological events. Asian jumping worms also tend to gather in large groups whenever they infest an area, resulting in most of the decaying plant material and other organic material being stripped out of the soil. Often, the only plants capable of developing in those conditions are invasive themselves!

Reporting

We are still learning about the Asian jumping worms spread in Indiana, so we are asking everyone to please report sightings. You can report them either online by going to the EDDMapS website or you can call 1-866-NOEXOTIC. We ask that you take a picture and tell us where you were when you saw the worms. You can also check the Report Invasive webpage for up-to-date information on all kinds of invasive species, or reach out to Bob Bruner, Purdue University Exotic Forest Pest Educator, by emailing rfbruner@purdue.edu. With your help, we can map out this worm and create effective plans to limit its presence in our state.

View the original article on the Purdue Landscape Report website: Asian Jumping Worms: How to ID this soil pest.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

Gardeners Asked to be Vigilant This Spring for Invasive Jumping Worm, Purdue Extension – FNR Got Nature? Blog

Fall webworms: Should you manage them?, Purdue Landscape Report

Mimosa Webworm, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Sod Webworms, Turf Science at Purdue University

Bagworm caterpillars are out feeding, be ready to spray your trees, Purdue Extension Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Got Nature? Blog

Landscape & Ornamentals: Bagworms, The Education Store

Purdue Plant Doctor App Suite, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Find an Arborist website, Trees are Good, International Society of Arboriculture (ISA)

ID That Tree – Video Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana, Purdue FNR web page list

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

Purdue Landscape Report: Recently, there has been an uptick in questions related to one of Indiana’s most notorious invasive pests: the emerald ash borer. Homeowners, businesses, even professionals have asked if ash trees are still present in Indiana, and if the insect is still a threat to our ecosystem. Emerald ash borer wreaked significant havoc among Indiana’s hardwoods, and a person could be forgiven for believing that there are no ash trees at all in our state, but this is simply not true. Ash still survives in Indiana and can be found both as ornamental plantings and in untended woodlots; unfortunately, emerald ash borer is also still present and just as deadly to them as ever. The question of protecting ash versus removal them is complex, but entomologists and tree specialists have learned from this insect’s invasion.

The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), a wood-boring insect native to Asia, is responsible for decimating ash (Fraxinus spp.) throughout the United States and elsewhere. In Indiana, this insect’s presence was confirmed in 2004, though it had probably been in the state for some time before then. Since its arrival, Hoosiers have been forced to watch as ash trees have rapidly declined and died due to the insect’s feeding and life cycle. The insect lays its eggs in crevices in the bark of an ash that is 8 to 10 years old, and after hatching, the new larvae begin to bore through the tree’s cambium tissue. The tree relies on its cambium tissue to transport water and nutrients and supply cells for new growth. Often, the only signs of the insect’s presence are a reduction in canopy coverage and D-shaped exit holes in the bark, indicating adult emergence. As time goes on, however, the tree will continue to lose canopy, experience limb death, and often have large chunks of bark detach. Unprotected trees will typically die within 2 to 5 years of infestation. Dead and dying ash trees represent a serious hazard to health and property as infestation will leave them extremely brittle. Brittle ash will often fall during weather events or even collapse over time as limbs fall off.

While emerald ash borer did significant damage to ash tree populations in Indiana, they did not destroy the population entirely. While virtually all untreated trees will eventually become infested, saplings with a trunk diameter of ½ to 1 inch will remain untouched, allowing annual replacement of trees to continue. Since the initial invasion killed so many trees, the borer’s populations have been proportionally reduced as well due to a lack of a food source. This combination of factors has created a cycle of growth and infestation that allows both populations to survive, but at significantly lower levels as compared to the period of the initial infestation. Unfortunately, this also means that emerald ash borer is now a permanent fixture in the hardwood ecosystem in Indiana.

Figure 2. This photo illustration shows three ash trees in Bloomington, Indiana, with different levels of canopy lost to the emerald ash borer. (Purdue Tree Doctor app illustration/Cliff Sadof)

While many may believe ash trees are a total loss, there are still options to protect ash tree and even rescue ash that have already been infested. The first step in this process is to determine the extent of damage in a given tree. As the cambium tissue is consume by ash borer larvae, the tree will experience a steady loss of canopy and limb death. The proportion of lost canopy makes a great indicator for treatment viability. For example, a tree that has only lost 10% of its canopy will normally respond well to treatment. As more canopy is lost, recovery is more challenging, until the tree has lost %30 of canopy coverage. After that point, there is very little chance that a rescue treatment will be successful, and removal will most likely be necessary. It is also important to remember that limb death may occur; these limbs will not recover and will need to be removed to avoid any potential hazards.

There are several insecticides with varying ranges of efficacy that can be used to manage emerald ash borer. These include imidacloprid, dinotefuran, azadirachtin, and emamectin benzoate. Several studies have been conducted to find the best combination of chemical and application type, such as the difference between using a soil drench compared to a trunk injection. While all of the above chemicals can be effective against the insect, the combination of emamectin benzoate applied through a trunk injection offers the best, longest lasting protection from infestation. This combination has a durable effect lasting for two years under dense infestations. However, the reduction in emerald ash borer populations have spread the distribution of the insect thinner, and longer intervals between treatments are possible. A ten-year study conducted by Purdue University demonstrated that treating trees once every three years provided sufficient protection from the beetles, while also showing that 4 to 5 years after last treatment coincided with an increase in damage to the trees. This same study also found that by six years post-treatment, the trees would decline to the point of making removal a necessity. This research concluded that increasing time between intervals after three years increased the risk of catastrophic damage due to emerald ash borer activity, thus the recommendation for three-year intervals.

Ultimately, many will see this as a financial issue: the cost of treatment over time against the cost of removal to avoid potential damages. The above study estimated the cost of treating a single tree with an emamectin benzoate injection at $300 per treatment. Since treatment only needs to happen once every three years, the cost per year per tree would be $100, approximately. Tree removal was estimated between $1800 and $3600, depending on tree location and other factors. Also consider replacement costs if you wanted to continue to grow ash in that area, and how long the tree would need to grow to match the size of the tree you just replaced. Additionally, add in any treatment costs to make sure it survives infestation. When looked at from this angle, maintaining regular treatment on rescuable trees would appear to be the most cost-effective route for managing ash. Any treatment plan should be discussed with a professional, such as a certified arborist.

Read the original article posted in the Purdue Landscape Report April 2025 Newsletter: Revisiting Ash Tree Protection.

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

New Hope for Fighting Ash Borer, Got Nature? Purdue Extension-FNR

Invasive Pest Species: Tools for Staging and Managing EAB in the Urban Forest, Got Nature?

Emerald Ash Borer, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Emerald Ash Borer Tools & Resources – Purdue Extension Entomology

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Tree Planting Part 2: Planting a Tree, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Indiana Invasive Plant List, Indiana Invasive Species Council, Purdue Entomology

Landscape Report Shares Importance of Soil Testing, Purdue FNR Extension

Find an Arborist website, Trees are Good, International Society of Arboriculture (ISA)

Tree Risk Management – The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

ID That Tree – Video Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

Conservation Tree Planting: Steps to Success, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Professional Forester, Indiana Forestry Woodland Owners Association

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Entomology

Purdue Landscape Report: Sawflies are frequent pests in the landscape that attack a wide variety of plants, from ornamental flowers to large trees. You might start to see them damaging plants around this time of year as the first generations hatch and begin to feed on foliage. They are often mistaken for caterpillars, which are the larval stages of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera). However, sawflies are actually wasp-like insects (Order Hymenoptera).

Let’s review how to tell them apart. Products that are labeled for caterpillars do not always work on sawflies, so proper identification is important.

- The most reliable characteristic are the prolegs. Sawflies have 6+ pairs of prolegs, or false legs, while caterpillars have < 6 pairs of prolegs. (Fig. 1)

- When disturbed, sawflies will lift their posterior into an “S” shape. Caterpillars don’t display this behavior. (Fig. 2)

Integrated management recommendations

Early in the year, before hatching starts, look for sawfly oviposition on your plants. This will vary depending on the species of sawfly. For example, the European Pine sawfly eggs look like yellow-orange spots evenly spaced on the needles (Fig. 3). The Bristly Roseslug sawfly uses her ovipositor to cut a slit into the leaf petiole where she inserts eggs. The gooseberry sawfly lays eggs on a leaf vein (Fig. 4).

If the eggs are readily visible, manual removal will help reduce the populations. This is best accomplished in early spring before the eggs hatch. Use a tool to smash the eggs, or prune of the affected plant material.

You may not notice any problem on the plant until you start to see holes appearing in the foliage. Monitor regularly in the spring for holes and “window pane” damage (Fig. 5). This is the time of year when sawflies are hatching, so don’t wait any longer to check your plants. Sawfly management is best accomplished when the larvae are still small. Prune or shake off the larvae from the plant, or spray with a biorational material so as not to disturb natural enemies and cause a secondary pest outbreak later in the summer.

For more information on sawfly biology, check out this five-minute video: Slaying Sawflies with Purdue Plant Doctor.

Specific management recommendations can be found on the Purdue Plant Doctor website. Type “sawfly” into the search and click on the species you would like to read more about!

Read the original article on Purdue Landscape Report: Sawflies: the caterpillar pests that are not caterpillars.

Ask the Expert: Pests in Your Woods, Purdue Extension – Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Report Spotted Lanternfly, Purdue Landscape Report

Invasive Species Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Purdue Plant Doctor, Purdue Extension

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana, Forestry & Natural Resources

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Alicia Kelley, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Coordinator

Purdue Extension – Entomology

Purdue Landscape Report: The bitter winter cold has finally passed us (or has it? It’s hard to tell in the Midwest)! The days are getting warmer and longer, and that means the insects are coming out of their overwintering stages. As you prepare for your landscaping and gardening this year, are you implementing preventative measures for pests? Now is the time to think about those strategies to minimize the damage to your plants.

Preventing pest issues is foundational to integrated pest management. The first step is always to start with healthy and clean plants. Don’t be afraid to bring a hand lens to the store and check for those hard-to-see pests! You don’t want to bring a problem home. Next, remember that many pests will thrive due to improper watering, light conditions, or fertilization. Avoid these issues by reviewing the recommendations for your plants and consulting a soil test. (Read more about why soil tests are essential!)

Finally, which pests/diseases do you anticipate? What are the most common pests on the plants in your landscape? Perhaps you have had issues in past years and know what to expect. Review the biology of these pests and consider implementing preventative measures now. Let’s look at a couple of examples of frequent landscape pests and some management options you can add to your list of spring preparations.

Spider Mites

Spider mites overwinter on the host plant or in leaf litter. Around this time of year, cool season mites such as spruce mites and boxwood mites are the dominant issue. Check your plants now for these spider mites, and scout regularly to make sure populations aren’t getting out of control. A rainy spring will help keep the pressure low. If you have to spray, avoid chemicals that will harm natural enemies, which are vital to spider mite management. (Learn more about spider mite management: Spider Mites on Ornamentals; and check out the Purdue Plant Doctor Quick Guide: Managing Spider Mite Mayhem)

Bagworms

Bagworms overwinter as eggs in the bags left on the tree. They’re frequent pests of arborvitae, junipers, and several other trees and shrubs. Take action now to prevent an infestation in the summer that requires costly pesticides. Manually remove the bags from your tree and drown them in soapy water. (Learn more about bagworm management: Bagworms).

Lace Bugs

Lace bugs may overwinter as eggs or adults, depending on the species. They become active again in the spring, so now is a good time to check for these pests. Focus on the undersides of the leaves where the pests are found. Lace bugs prefer hosts planted in sunny areas with a lack of plant diversity, so consider including some flowering plants in your landscape to provide pollen and nectar to beneficials. (Learn more about Lace bug management from the Purdue Plant Doctor Quick Guide: Managing Lace bugs).

What pests do you encounter in the landscape? Take a moment to review their biology and your options for preventative management. Be proactive now and reduce your pest problems for the season ahead. Read the original article, Insects are waking up – are you prepared?

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Native Trees of the Midwest, Purdue University Press

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Episode 11 – Exploring the challenges of Invasive Species, Habitat University-Natural Resource University

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Spotted Lanternfly Found in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Alicia Kelley, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Coordinator

Purdue Extension – Entomology

The Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Laboratory (PPDL) proudly presents its latest Annual Report, offering a comprehensive overview of the year’s most significant insights, diagnostics, and trends. This essential document covers critical topics such as spruce-tordon uptake, hosta virus X, ophiostoma ulmi, diamond back moth, lettuce slime mold, and bentgrass dollar spot. As an indispensable resource for growers, researchers, and the public, PPDL remains at the forefront of providing expert analysis on plant diseases, insect identification, and environmental concerns throughout Indiana and beyond.

Visit the PPDL Annual Reports webpage to find the 2024 report and view past reports.

About PPDL:

The Plant and Pest Diagnostic Laboratory (PPDL) remains dedicated to helping protect Indiana’s agriculture, the green industry, and individual landscapes, by providing rapid and reliable diagnostic services for plant disease and pest problems. PPDL also provides appropriate pest management strategies and diagnostics training. They are a participating member lab in the National Plant Diagnostic Network (NPDN), a consortium of Land Grant University diagnostic laboratories established to help protect our nation’s plant biosecurity infrastructure.

Resources:

Find an Arborist, International Society of Arboriculture

Diseases in Hardwood Tree Plantings, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Invasive Species, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Tree Defect Identification, The Education Store

Tree Wound and Healing, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Plant & Pest Diagnostic Laboratory (PPDL)

Purdue Botany and Plant Pathology

Recent Posts

- Uniting Indiana Residents Against Invasive Species

Posted: February 27, 2026 in Community Development, Invasive Insects, Wildlife - Purdue Extension: Empowering Indiana Through Innovation, Education and Community Impact

Posted: January 28, 2026 in Community Development, How To, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Natural Resource Planning, Woodlands - Spotted Lanternflies on the Move! – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: October 13, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Animal Species, Invasive Insects, Wildlife, Woodlands - October Is Firewood Month: Protect Indiana’s Forests by Making Smart Choices

Posted: in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - Cryptomeria Scale on Christmas Trees, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: September 9, 2025 in Invasive Insects, Woodlands - How to ID Asian Jumping Worms, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: July 2, 2025 in How To, Invasive Insects, Wildlife - Revisiting Ash Tree Protection, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: May 23, 2025 in Forests and Street Trees, Invasive Insects, Wildlife, Woodlands - Sawflies: Caterpillar Pests but not Caterpillars – PLR

Posted: in Invasive Insects, Wildlife, Woodlands - Prepared for Insects Waking Up? – PLR

Posted: March 26, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - PPDL’s 2024 Annual Report – Enhancing Plant Health

Posted: March 21, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Wildlife

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands