Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

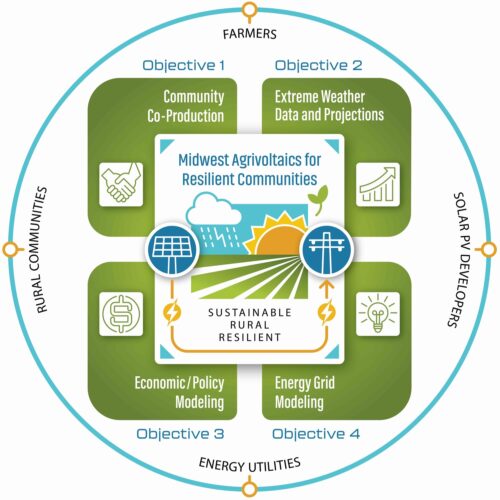

Institute for Sustainable Future News: Rural communities across the Midwest, whose agricultural economies and energy infrastructure are frequently threatened by extreme weather events such as hailstorms, heat waves and high winds, are getting a new lifeline through a National Science Foundation–funded project at Purdue University.

The NSF’s Regional Resilience Innovation Incubator (R2I2): Midwest Agrivoltaics for Resilient Communities (MARC), supported under grant #2519425, is designed to help these communities become more resilient by combining agriculture with solar energy — to improve resilience from local to national levels. This phase 1 grant positions the team to compete for a Phase 2 grant worth up to $15M for an additional 5 years.

Agrivoltaics, which allows the dual use of land for agricultural production and solar energy generation, holds great promise to diversify farm income, reduce power outages, and increase energy production as energy demand soars. But agrivoltaics systems have seen slow adoption in the Midwest due to uncertainties about land use trade-offs, lack of trusted information about community impacts and benefits, and concerns from farmers and communities about economic viability and performance under extreme weather. The incubator intends to bring together community members, stakeholders and experts to fill those gaps.

“When hail ruins a harvest, heat strains livestock, or windstorms cut electricity, farmers and their communities are hit hard. Our goal is to understand how agrivoltaics can make our nation’s rural communities more resilient and prosperous,” stated Dr. Dan Chavas, principal investigator.

This project is an ambitious interdisciplinary effort that brings together experts across atmospheric science, agriculture, energy systems, economics, and social science – all housed here at Purdue University across the Colleges of Science, Engineering, Polytechnic and Agriculture, including Extension. Purdue’s Institute for a Sustainable Future (ISF) played an integral role in the development and continued support of the project. ISF provided strategic research teaming support, helping assemble an initial interdisciplinary team of faculty address the complex social, economic and technical aspects of agrivoltaics. This collaborative approach strengthened the project’s ability to meet NSF’s goals for resilience, innovation and community engagement.

The project is led by Purdue University experts across multiple disciplines:

Dr. Dan Chavas is a Professor of atmospheric science in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University and is part of the leadership team for the Purdue Institute for a Sustainable Future. Dan is the principal investigator and will lead the project’s effort on extreme weather and its risks to agriculture and solar energy systems.

Dr. Aaron Thompson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University and Director of the Center for Community and Environmental Design. Dr. Thompson is also part of the leadership team for the Purdue Institute for a Sustainable Future. His research applies social-ecological science to sustainable landscape development, focusing on agricultural conservation and nature-based solutions. He teaches courses in ecological planning, research methods, and sustainable development.

Dr. Xiaonan Lu is an Associate Professor in the School of Engineering Technology and the Elmore Family School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (by courtesy) at Purdue University, also holding a joint appointment with Argonne National Laboratory. Xiaonan will lead the efforts of resilience quantification and energy modeling of rural electric power grids considering impacts of distributed energy resources and microgrids.

Dr. Kara Salazar is Assistant Program Leader for community development with Purdue Extension and sustainable communities extension specialist with Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. Kara will co-lead community engagement and social science efforts.

Dr. Juan Sesmero is a Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Purdue University. He will lead the economic modeling of agrivoltaics technology deployment and assess its economic impacts on community resilience.

The team is also comprised of additional Purdue and industry collaborators. Key project activities include:

- Building Trust & Community Engagement: Working directly with community, agriculture, and energy partners in co-designing strategies for agrivoltaics deployment to support local communities in the rural Midwest.

- Quantifying Extreme Weather Resilience Benefits: Analyzing how extreme weather events—hail, heat, wind—impact both agriculture and the power grid and how agrivoltaics may be able to reduce these impacts on communities.

- Economic and Power Grid Models & Community Tools: Developing tools, metrics and models that incorporate local conditions to help farmers, planners and communities understand risks and potential benefits to make informed decisions about agrivoltaics.

- Identifying Agrivoltaics Pathways: Evaluating which agrivoltaic configurations are suitable under different land, climatic, and economic conditions.

- Roadmap & Policy Framework: Producing a dynamic roadmap and a policy/planning framework aimed at facilitating broader, community-supported adoption of agrivoltaics.

By the end of the initial funding period, the incubator expects to deliver viable agrivoltaics models and pathways tailored to varying Midwest geographies and farming systems; decision-support tools for landowners, communities, and policymakers; as well as strengthened partnerships among academia, industry, government and local communities.

“For farmers, adapting to changing conditions, markets, and policies has always been crucial for success. Agrivoltaics offers an opportunity to maintain land in production while diversifying revenue by tapping into a growing segment of the energy market,” stated Dr. Aaron Thompson. “This initiative focuses on answering key questions about balancing reliable energy income with the production of food and fiber that are essential for maintaining the strength of Indiana’s agricultural economy.”

For more information about the NSF Regional Resilience Innovation Incubator, and the Midwest Agrivoltaics Incubator, visit the project website.

View the original article here: Purdue Leads NSF-Funded Midwest Agrivoltaics Incubator to Boost Rural Energy and Economic Resilience to Extreme Weather.

Resources:

Community Development, Purdue Extension

Wind Energy, Purdue Community Development

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

Environmental Planning in Community Plans, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Enhancing the Value of Public Spaces Program, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Enhancing the Value of Public Spaces: Creating Healthy Communities, The Education Store

Conservation through Community Leadership, The Education Store

Conservation through Community Leadership, Purdue Extension You Tube Channel

Implementation Examples of Smart Growth Strategies in Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Conservation Through Community Leadership, The Education Store

Community Planning Playlist, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

One Water Approach to Water Resources Management, The Education Store

Rainscaping Education Program, Purdue Extension

Rainscaping and Rain Gardens, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Indiana Creek Watershed Project – Keys to Success, Partnerships and People, Purdue Extension You Tube Channel

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Subscribe – Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources Calendar, workshops and Conferences

Institute for a Sustainable Future

Purdue University

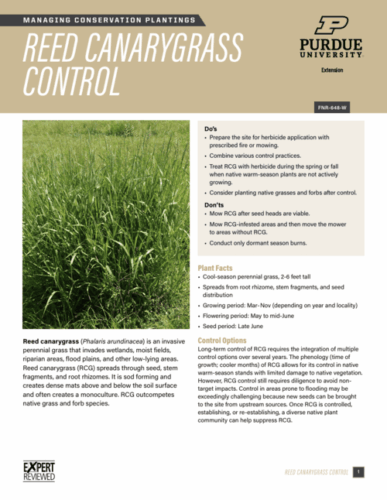

Uncover the challenges posed by reed canarygrass, an invasive perennial grass that threatens conservation plantings, wetlands and low-lying areas. This guide details control options for reed canarygrass. Essential for conservationists and land managers dedicated to preserving native ecosystems: Reed Canarygrass Control.

Uncover the challenges posed by reed canarygrass, an invasive perennial grass that threatens conservation plantings, wetlands and low-lying areas. This guide details control options for reed canarygrass. Essential for conservationists and land managers dedicated to preserving native ecosystems: Reed Canarygrass Control.

Check out the Managing Conservation Plantings Series which include details on how to control invasive species and other problematic plants in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) plantings and native warm-season grass and wildflower conservation plantings.

Publications in this series include:

- Golden Rod Control

- Thinning Native Warm-Season Grasses

- Sericea Lespedeza Control

- Woody Encroachment and Woody Invasives

- Jonhsongrass Control

- Reed Canarygrass Control

- Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved)

- Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

- Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control

Resources:

Deer Impact Toolbox & Grassland Management, Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Pond and Wildlife Management, Purdue Extension

Forestry for the Birds Virtual Tour and Pocket Guide, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots and Native Grass and Forb Plantings – Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Tips for Evaluating a First Year Native Grass and Forb Plantings, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Drone Seeding Native Grasses and Forbs: Project Overview & Drone Setup, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching Unit 1: Animal Diversity and Tracking, The Education Store

Nature of Teaching, Purdue College of Agriculture

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Subscribe Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Discover how to manage non-native cool-season grasses like tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass in native conservation plantings. This guide reveals how these invasive species form dense sod layers, which limits wildlife mobility, and also provides control options for these invasive species. Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses is essential for anyone dedicated to preserving native ecosystems and enhancing biodiversity.

Discover how to manage non-native cool-season grasses like tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass in native conservation plantings. This guide reveals how these invasive species form dense sod layers, which limits wildlife mobility, and also provides control options for these invasive species. Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses is essential for anyone dedicated to preserving native ecosystems and enhancing biodiversity.

Check out the Managing Conservation Plantings Series which include details on how to control invasive species and other problematic plants in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) plantings and native warm-season grass and wildflower conservation plantings.

Publications in this series include:

- Golden Rod Control

- Thinning Native Warm-Season Grasses

- Sericea Lespedeza Control

- Woody Encroachment and Woody Invasives

- Jonhsongrass Control

- Reed Canarygrass Control

- Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved)

- Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

- Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control

Resources:

Deer Impact Toolbox & Grassland Management, Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Pond and Wildlife Management, Purdue Extension

Forestry for the Birds Virtual Tour and Pocket Guide, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots and Native Grass and Forb Plantings – Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Tips for Evaluating a First Year Native Grass and Forb Plantings, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Drone Seeding Native Grasses and Forbs: Project Overview & Drone Setup, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching Unit 1: Animal Diversity and Tracking, The Education Store

Nature of Teaching, Purdue College of Agriculture

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Subscribe Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Once the leaves have fallen and the landscape is dominated by shades of brown and gray, bright colors like red catch our attention. There are several red fruits that we may encounter in the late fall and winter here in Indiana that add some color to the landscape. These fruits are retained on trees and shrubs for a variety of reasons. Some are not as palatable to wildlife, so they are eaten later in the season. Some are more resistant to freeze damage and thus cling to branches longer than delicate fruits. There may also be an advantage to their appearance. Many of these plants have seeds dispersed by wildlife like birds, which eat the seeds and excrete them later, providing an opportunity to produce new plants away from the parent. Many birds can see much of the same color spectrum we do, plus enhanced vision in the ultra-violet bands. Brightly-colored seeds with waxy skins may reflect more ultra-violet light and be more noticeable to the birds.

What are some of those red fruits?

One family of plants accounts for several red fruit we can see in late fall and winter, the rose family. This family includes apples, plums, cherries, hawthorns, pears and others as well as the roses. In Indiana we have several hawthorns (Crataegus species) that produce a fruit resembling a tiny apple. These vary in size by species but are typically ¼ to ½ inch diameter and often held in clusters. Hawthorns are typically small trees and may have long thin thorns on the twigs.

Another rose family member are the apples and crabapples with some small native trees like sweet crabapple, Malus coronaria, and several varieties of fruit-bearing apples and ornamental crabapples planted but sometimes escaping to natural areas. While our native crabapples are usually about 1-2 inches diameter and green to yellow, the domesticated apples and crabapples often have red fruit in various sizes from large apples to ½ inch diameter crabapples.

We also have several beautiful native roses in Indiana, and a particularly problematic exotic invasive rose in multiflora rose. Unfortunately, you are more likely to encounter multiflora rose with small ¼ inch clusters of red fruit. Our native roses typically have larger fruit and fewer fruit per cluster.

Holly is also noted for red fruit and some being evergreen as well. Our native Indiana hollies are all deciduous, losing their leaves in the fall but often retaining the red fruit on the female plants into winter. The most widespread species is winterberry, Ilex verticillate, a shrub which is seeing more use ornamentally due to its striking red fruit held past Christmas most years. American holly, an evergreen broadleaved tree, is well-known for its glossy, spiny foliage and red fruit on the female trees. Although not native to Indiana, it is spreading from plantings into natural areas. Several evergreen hollies from Europe and Asia are also common in ornamental plantings and may escape into natural areas.

Not only are these late-season showy fruit attractive, but they also provide some important nourishment for wildlife when the many other fruits are long-gone.

Resources:

Ask An Expert: Holidays in the Wild, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Selecting a Real Christmas Tree, Got Nature? Blog Post, Purdue Extension – FNR

Tips on How You Can Recycle Your Christmas Tree, Got Nature? Blog Post, Purdue Extension – FNR

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

ID That Tree: Prickly Ash, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Tree Planting Part 1: Choosing a Tree, video, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center

Purdue Department of Forestry & Natural Resources

Discover how to effectively manage the invasive common and cut-leaved teasel, which threatens open areas like prairies, savannas, sedge meadows, roadsides and conservation plantings. This publication provides essential information for exploring effective control options. Essential reading for conservationists and land managers interested in grassland ecosystems: Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved).

Discover how to effectively manage the invasive common and cut-leaved teasel, which threatens open areas like prairies, savannas, sedge meadows, roadsides and conservation plantings. This publication provides essential information for exploring effective control options. Essential reading for conservationists and land managers interested in grassland ecosystems: Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved).

Check out the Managing Conservation Plantings Series which include details on how to control invasive species and other problematic plants in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) plantings and native warm-season grass and wildflower conservation plantings.

Publications in this series include:

- Golden Rod Control

- Thinning Native Warm-Season Grasses

- Sericea Lespedeza Control

- Woody Encroachment and Woody Invasives

- Jonhsongrass Control

- Reed Canarygrass Control

- Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved)

- Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

- Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control

Resources:

Deer Impact Toolbox & Grassland Management, Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Pond and Wildlife Management, Purdue Extension

Forestry for the Birds Virtual Tour and Pocket Guide, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots and Native Grass and Forb Plantings – Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Tips for Evaluating a First Year Native Grass and Forb Plantings, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Drone Seeding Native Grasses and Forbs: Project Overview & Drone Setup, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching Unit 1: Animal Diversity and Tracking, The Education Store

Nature of Teaching, Purdue College of Agriculture

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Subscribe Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The Purdue FNR extension team was named as a recipient of the Family Forests Comprehensive Education Program Award presented by the National Woodland Owners Association (NWOA) and National Association of University Forest Resources Programs (NAUFRP).

The award, which is the nation’s top honor for forestry extension programming, recognizes superior performance across nine rigorous criteria, celebrating the standard of excellence for the profession. Drs. Zhao Ma and Mike Saunders received the award on the team’s behalf at the NAUFRP annual meeting at the 2025 Society of American Foresters (SAF) national convention in Hartford, Connecticut, in October.

The Family Forests Comprehensive Education Program Award criteria includes:

The Family Forests Comprehensive Education Program Award criteria includes:

- Faculty involved (including number and multi-disciplinary involvement)

- Educational needs assessment (including involvement of clients)

- Educational materials, events and other resources used

- Applied research incorporated

- Collaborations among disciplines, agencies and organizations

- Results, impacts or outcomes

- Evidence of program quality

- Degree of innovation

- Emulation of the program by others

NAUFRP extension chair Bill Hubbard, who oversaw the competition said “After a thorough review by our three judges and myself, the committee determined that both the University of Minnesota and Purdue University programs demonstrated such profound and differentiated excellence across the nine core criteria that it was decided to recognize them both.”

According to the NAUFRP announcement, “Purdue’s program was honored for its massive scale, its deep connection to a long-term research asset, and its commitment to building future workforce capacity.”

Program highlights include:

- HEE Integration: The program directly integrates findings from the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment (HEE)—a 100-year research study—into its curriculum, providing landowners with unbiased, real-time data on management issues like oak/hickory regeneration and wildlife response to timber harvest.

- Economic & Ecological Scale: The program supports the multibillion-dollar hardwood industry by having an impact on over 57,000 acres and engaging a network of tens of thousands of landowners through its extensive publications.

- Curricular Innovation: Purdue was recognized for its pioneering move to formally incorporate Extension training into its undergraduate and graduate curricula, ensuring the next generation of forestry professionals is equipped with crucial outreach skills.

The Purdue team includes five faculty and nine professional staff members. Over the past five years, the group boasts many standout accomplishments including:

- Development of publications that have been downloaded more than 2.1 million times

- Publication and dissemination of the Indiana Woodland Steward newsletter, which has reached more than 31,000 family forest owners, impacting more than 1.2 million acres

- Creation of 215 training programs, which reached more than 50,000 landowners, impacting more than 57,000 acres of woodlands

- Production of 249 videos, downloaded more than 750,000 times, and 38 podcast episodes, reaching more than 50,000 listeners in the United States alone. Videos can be accessed on the FNR Extension YouTube channel. The Habitat University podcast is available as part of the Natural Resources University network.

- Awarded more than $4.4 million in extramural funding for faculty and staff

- Formally incorporated undergraduate and graduate students in Extension at the programmatic level

In the nomination packet, team personnel stated “We aim to address family forest owner needs through collaboration with many stakeholders. Our family forest education serves family forest owners, professional advisors, an industry that receives most of their product base from family forests and the general public who influence policy decisions affecting family forest owners. Our program focuses on adoption or maintenance of stewardship practices (e.g., invasive plant control, timber harvesting), developing or improving forestland planning, and engaging peer and professional advice. In doing these, family forest owners can make informed decisions that meet their personal land management objectives while enhancing the resource for all residents.”

Team members include:

- Jarred Brooke – Extension wildlife specialist; Specializing in wildlife conservation, habitat management and deer impact

- Diana Evans – Extension and web communications specialist; Specializing in website design and communications

- Lenny Farlee – Extension forester; Specializing in forest regeneration, hardwood management and genetics

- Dr. Rado Gazo – professor of wood processing and industrial engineering; Specializing in secondary wood products manufacturing processes

- Dr. Eva Haviarova – professor of wood products; Specializing in strength design and product engineering of furniture and product sustainability

- Liz Jackson – engagement specialist with the Indiana Forestry and Woodland Owners, Walnut Council and Purdue Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center; Specializing in black walnut, oaks and landowner engagement

- Dr. Doug Jacobs – Fred M. van Eck professor of forest biology; Specializing in forest ecology, silviculture, regeneration and restoration

- Dr. Brian MacGowan – Extension wildlife specialist and extension coordinator; Specializing in wildlife habitat management, wildlife conservation and wildlife damage

- Wendy Mayer – communications coordinator; Specializing in social media and communications

- Jessica Outcalt – natural resources training specialist; Specializing in natural resources, conservation and professional development

- Henry Quesada – professor, assistant director of Extension and ANR program leader; Specializing in wood products, hardwood lumber, biomaterials, hardwood markets and industry

- Ron Rathfon – regional extension forester; Specializing in forest management, timber marketing, tree planting, oak regeneration and ecology and invasive vegetation management

- Dr. Mike Saunders – professor of ecology and natural resources; Specializing in disturbance-based silviculture, growth and yield, modeling, disturbance ecology and management effects on wood quality.

- Kat Shay – HEE forest project coordinator; Specializing in environmental science and restoration

From 2020 to 2024, the FNR Family Forest Education extension team conducted 788 programs, covering 1,005 sessions and including more than 50,000 individual contacts.

To view the original article along with other news and stories posted on the Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources website view: FNR Extension Team Receives Family Forests Comprehensive Education Award.

Resources:

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners YouTube Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR

Wildlife Habitat Hint YouTube Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR

Woodland Management Moment YouTube Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR

Invasive Species YouTube Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR

Forest Management for the Private Woodland Owner Course – Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

Finding help from a professional forester, Indiana Forestry & Woodland Owners Association

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Indiana Woodland Steward Institute

Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment (HEE)

Hardwood Tree Improvement & Regeneration Center (HTIRC)

Help the Hellbender

The Nature of Teaching

Pond and Wildlife Management, website

Community Development, Purdue Extension

Subscribe Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The 2025 issue of Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s magazine, The Helm, is now available. This annual publication is a collection of program research, outreach and education success stories, as well as ongoing activities to address coastal concerns. This issue covers this year’s Shipboard Science Immersion that took place on Lake Michigan, our long-standing team engaged in AIS prevention outreach, our new specialists diving into coastal resilience issues, and past and present program leadership.

Highlights from the newsletter include:

- Educators engage with Great Lakes scientists aboard the Lake Guardian

Teachers joined researchers on Lake Michigan aboard the R/V Lake Guardian, collecting samples, learning new field techniques, and bringing Great Lakes science back to their students. - Scientists and educators investigate Lake Michigan biological hotspots

Every year when a group of Great Lakes educators spend 6–7 days aboard the Lake Guardian as part of the Shipboard Science Immersion, they work side-by-side with scientists engaging in real monitoring work. - IISG looks back on 30 years of AIS outreach

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is in the midst of its 30th year of dedicated outreach to address the spread of aquatic invasive species (AIS) in Great Lakes waters. - Coastal communities face challenges in managing beach sand and structures

Beginning in 2025, IISD has not one, but two coastal resilience specialists who are providing support for communities along the southern Lake Michigan shore. - Shaping the Shoreline: Video Series

Explore how natural and engineered structures shape our Great Lakes coastlines. - Stuart Carlton is the new IISG director

Stuart Carlton, longtime Sea Grant communicator and leader, steps into the director role—continuing IISG’s mission of connecting research, education, and outreach. - Tomas Höök reflects on his Sea Grant legacy

After more than a decade as director, Tomas Höök looks back on milestones that shaped IISG’s growth and lasting partnerships.

To view the full newsletter visit: The Helm.

More Resources:

Prescription For Safety: How to Dispose of Unwanted Household Medicine, IISG Publications

A Guide to Marketing for Small-Scale Aquaculture Producers, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

A Guide to Small-Scale Fish Processing Using Local Kitchen Facilities, The Education Store

Marine Shrimp Biofloc Systems: Basic Management Practices, The Education Store

Sustainable Aquaculture: What does it mean to you?, The Education Store

The Benefits of Seafood Consumption The Education Store

Walleye Farmed Fish Fact Sheet: A Guide for Seafood Consumers, The Education Store

Fish Muscle Hydrolysate, The Education Store

Fish Cleaning with Purdue Extension County Extension Director, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Aquatics & Fisheries, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Eat Midwest Fish, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant online resource hub

Community Development, Purdue Extension

Climate Change and Sustainable Development, The Education Store

Climate Change: Are you preparing for it?, The Education Store

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Diana Evans, Extension & Web Communications Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

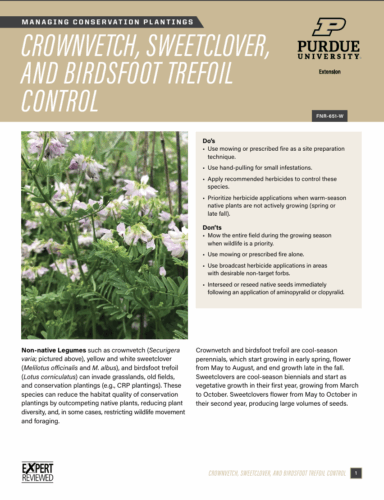

Discover the impact of non-native legumes like crownvetch, sweetclover, and birdsfoot trefoil on grasslands and conservation plantings. This guide provides control options for these non-native legumes. Essential reading for conservationists and land managers interested in grassland ecosystems: Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control.

Discover the impact of non-native legumes like crownvetch, sweetclover, and birdsfoot trefoil on grasslands and conservation plantings. This guide provides control options for these non-native legumes. Essential reading for conservationists and land managers interested in grassland ecosystems: Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control.

Check out the Managing Conservation Plantings Series which include details on how to control invasive species and other problematic plants in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) plantings and native warm-season grass and wildflower conservation plantings.

Publications in this series include:

- Golden Rod Control

- Thinning Native Warm-Season Grasses

- Sericea Lespedeza Control

- Woody Encroachment and Woody Invasives

- Jonhsongrass Control

- Reed Canarygrass Control

- Teasel Control (Common and Cut Leaved)

- Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

- Crownvetch, Sweetclover and Birdsfoot Trefoil Control

Resources:

Deer Impact Toolbox & Grassland Management, Purdue Extension Pond and Wildlife Management

Pond and Wildlife Management, Purdue Extension

Forestry for the Birds Virtual Tour and Pocket Guide, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Frost Seeding to Establish Wildlife Food Plots and Native Grass and Forb Plantings – Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Tips for Evaluating a First Year Native Grass and Forb Plantings, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Drone Seeding Native Grasses and Forbs: Project Overview & Drone Setup, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

A Template for Your Wildlife Habitat Management Plan, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube channel

Nature of Teaching Unit 1: Animal Diversity and Tracking, The Education Store

Nature of Teaching, Purdue College of Agriculture

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Report Invasive, Purdue Extension

Subscribe Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dive into the latest stories from the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) Newsletter which highlights research, outreach, and partnerships making a difference across the Great Lakes region. In this issue, explore how communities, scientists and educators are working together to protect water quality, strengthen coastal resilience, and inspire stewardship.

Dive into the latest stories from the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) Newsletter which highlights research, outreach, and partnerships making a difference across the Great Lakes region. In this issue, explore how communities, scientists and educators are working together to protect water quality, strengthen coastal resilience, and inspire stewardship.

Highlights from the newsletter include:

- IISG has a long history of supporting teachers through Great Lakes activities and resources

Read the blog from Stuart Carlton. - Freshwater jellyfish may increase in numbers as Illinois and Indiana waters continue to warm

A closer look at how climate trends are affecting unexpected species in our region’s freshwater systems. - New step-by-step guide and veterinary brochures expand UnwantedMeds.org resources

New tools help communities safely dispose of unwanted or expired medicine—from household to veterinary use—reducing pollution and protecting public health. - The Know Your H₂O Kit gets a real-world lab test by middle schoolers

Students dove into hands-on learning with IISG’s Know Your H₂O Kit, testing their local water and connecting science concepts to real environmental data. - Educators engage with Great Lakes scientists aboard the Lake Guardian

Teachers joined researchers on Lake Michigan aboard the R/V Lake Guardian, collecting samples, learning new field techniques, and bringing Great Lakes science back to their students. - IISG looks back on 30 years of AIS outreach

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant is in the midst of its 30th year of dedicated outreach to address the spread of aquatic invasive species (AIS) in Great Lakes waters. - Coastal communities face challenges in managing beach sand and structures

Beginning in 2025, IISD has not one, but two coastal resilience specialists who are providing support for communities along the southern Lake Michigan shore. - The Helm

Our latest edition of The Helm brings together insights from field research, outreach efforts, and education across the Great Lakes region. - Shaping the Shoreline: Video Series

Explore how natural and engineered structures shape our Great Lakes coastlines. - Welcome Stuart Carlton, new IISG director

Stuart Carlton, longtime Sea Grant communicator and leader, steps into the director role—continuing IISG’s mission of connecting research, education, and outreach. - Tomas Höök reflects on a legacy of leadership, collaboration and impact at IISG

After more than a decade as director, Tomas Höök looks back on milestones that shaped IISG’s growth and lasting partnerships.

Subscribe to the IISG newsletter by sending your name and email to iisg@purdue.edu. To view the full newsletter visit: Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) Quarterly Newsletter.

More Resources:

Prescription For Safety: How to Dispose of Unwanted Household Medicine, IISG Publications

A Guide to Marketing for Small-Scale Aquaculture Producers, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

A Guide to Small-Scale Fish Processing Using Local Kitchen Facilities, The Education Store

Marine Shrimp Biofloc Systems: Basic Management Practices, The Education Store

Sustainable Aquaculture: What does it mean to you?, The Education Store

The Benefits of Seafood Consumption The Education Store

Walleye Farmed Fish Fact Sheet: A Guide for Seafood Consumers, The Education Store

Fish Muscle Hydrolysate, The Education Store

Fish Cleaning with Purdue Extension County Extension Director, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Aquatics & Fisheries, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Eat Midwest Fish, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant online resource hub

Community Development, Purdue Extension

Climate Change and Sustainable Development, The Education Store

Climate Change: Are you preparing for it?, The Education Store

Natty Morrison, Communications Coordinator

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Diana Evans, Extension & Web Communications Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

MyDNR, Indiana’s Outdoor Newsletter: There are many options for enjoying outdoor recreation across Indiana this fall, especially with deer hunting season upon us. Learn more about deer hunting, how to support healthy wildlife populations, important regulations and how your hunting can support Hoosiers in need. Pay special attention to deer regulation changes, season dates and the importance of purchasing your license.

- Reduction Zone Season: Sept. 15, 2025 – Jan. 31, 2026

- Archery Season: Oct. 1, 2025 – Jan. 4, 2026

- Firearms Season: Nov. 15 – Nov. 30, 2025

- Muzzleloader Season: Dec. 6- Dec. 21, 2025

Deer Hunting Regulation Changes

Indiana DNR has made big changes to Indiana’s deer hunting rules. These changes are in effect for the 2025-2026 hunting season. The changes were made, in part, to make Indiana’s hunting regulations easier to understand.

Rule changes include:

- The statewide bag limit is now 6 antlerless deer and 1 antlered deer.

- A newly created county antlerless bag limit replaces the season antlerless bag limits and county bonus antlerless quotas. Because of this change, the new multi-season antlerless license has replaced the bonus antlerless license.

- Antlerless deer cannot be taken with a firearm during firearms season at Fish & Wildlife areas.

- Only 1 antlered and 2 antlerless deer can be taken with the bundle license.

- The use of crossbow equipment is now allowed using the archery license.

- Portable tree stands and ground blinds can now be placed on DNR properties in Deer Reduction Zones between noon Sept. 1 and Feb. 8.

- State law prohibits the use of drones (unmanned aerial aircraft) to search for, scout, locate or detect a wild animal during the hunting season and for 14 days prior to the hunting season for that animal.

- Hunters can now use rifles with a centerfire cartridge that has a bullet diameter of .219 inches (5.56 mm) or larger on both public and private lands.

For questions about equipment, regulations or changes in them, or which license you need, contact the Deer Information Line at INDeerInfo@dnr.IN.gov or 812-334-3795.

View a webinar recording explaining deer regulation changes.

Hunting Safety Tips and Reminders

Indiana DNR reminds you to stay safe this deer season. Hunting injuries most commonly involve elevated platforms and tree stands, so stay safe by following the guidelines below.

Tree stand safety before the hunt:

- Read, understand, and follow the tree stand manufacturer’s instructions.

- Check tree stands and equipment for wear, fatigue, rust, and cracks or loose nuts/bolts, paying particularly close attention to parts made of material other than metal.

- Practice at ground level with a responsible adult. If you need to sight in your equipment, find a shooting range near you.

- Learn how to properly wear your full-body safety harness.

- Make a hunt plan and share it with someone before your hunt.

- Wear your full-body safety harness.

- Use a tree stand safety rope.

- Make certain to attach your harness to the tree or tree stand safety rope before leaving the ground and check that it remains attached to the tree or tree stand safety rope until you return to the ground.

- Maintain three points of contact during ascent and descent.

- Wear boots with nonslip soles.

- Use a haul line to raise and lower firearms, bows, and other hunting gear.

- Make sure firearms are unloaded, action is open, and safety is on before attaching them to the haul line.

General reminders:

- Hunter Orange – know when to wear it and how much is needed on a ground blind

- Hunter orange is required for all deer hunters during youth, firearms, and muzzleloader season. Hunter orange must be worn at all times during the hunt, including walking to and from the hunting location. Regardless of hunting equipment being used (archery, crossbow or firearm), if it is firearms season, you are required to wear hunter orange.

- A ground blind must have at least 144 square inches of hunter orange material that is visible from any direction during any season in which a hunter is already required to wear hunter orange.

- Firearm Safety – Treat every firearm as if it is loaded, keep the muzzle pointed in a safe direction, keep your finger off the trigger until you are ready to shoot, and be sure of your target and what is beyond it.

- Print and complete a Landowner Permission Form if hunting on private land that isn’t your own.

- Remember to complete and attach a deer transportation tag immediately upon taking a deer. The tag should be attached to the deer during transportation and any time the deer is unattended.

Always bring emergency equipment with you on your hunt, such as a cellphone, flashlight, small first aid kit and extra water.

Read more about the guidelines and property rules here: Fish & Wildlife Properties.

Deer Reduction Zones

For information or any questions, view: Deer Reduction Zones.

Deer Disease Updates

Chronic wasting disease (CWD), a fatal disease impacting white-tailed deer, has been detected in wild deer in two areas of Indiana: LaGrange County and Posey County. These detections resulted in a CWD Positive Area including LaGrange, Noble, Steuben, and DeKalb counties and a one-year CWD Enhanced Surveillance Zone including Posey, Vanderburgh, and Gibson counties.

DNR offers free, statewide CWD testing for hunters by either taking your deer to one of DNR’s drop-off coolers at select Fish & Wildlife areas (FWAs), state parks, state fish hatcheries (SFHs) or through advertised private businesses such as taxidermists. These options are available during all seasons. Find out more about how to get your deer tested here: Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD).

Resources:

Ask an Expert: Wildlife Food Plots, video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 2, Hanging & Skinning, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 3, Deboning, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 4, Cutting, Grinding & Packaging, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Deer Harvest Data Collection, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, Purdue Extension

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, Purdue Extension

Handling Harvested Deer Ask an Expert? video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners: Managing Deer Damage to Young Trees, video, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Integrated Deer Management Project, Purdue FNR

New Deer Impact Toolbox, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Division of Fish and Wildlife, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- Uniting Indiana Residents Against Invasive Species

Posted: February 27, 2026 in Community Development, Invasive Insects, Wildlife - Have You Seen a Soaring Eagle Lately? Morning Ag Clips

Posted: February 25, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Register for Natural Resources Teacher Institute’s Class of 2026

Posted: February 19, 2026 in Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Applications Open for the 2026 Lake Guardian Shipboard Science Immersion

Posted: in Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Great Lakes, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Fragrant Sumac

Posted: February 4, 2026 in Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Woodsy Owl Edition for Educational Learning, USDA – U.S. Forest Service

Posted: January 21, 2026 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Opt-in to the Deer Management Survey, MyDNR

Posted: January 12, 2026 in Forestry, Wildlife - Indiana Woodland Steward Newsletter, The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment

Posted: January 7, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - FNR Extension Offering Forest Management for the Private Woodland Owner Course in Spring 2026

Posted: January 5, 2026 in Forestry, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - ID That Tree: Sugarberry

Posted: December 12, 2025 in Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands