Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the persimmon or Diospyros virginiana, one of Indiana’s fruit producing trees.

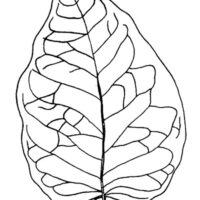

The alternately held leaves of persimmon are oval shaped with smooth margins, with no lobes or teeth. The thick dark green leaves turn yellow or reddish-purple in the fall. The buds are dark colored, while leaf stems are light brown.

The bark resembles alligator hide with deep broken ridges, often with an orange coloring between the ridges.

The fruit, a pumpkin orange colored fleshy plum-like fruit, is a standout characteristic and is favored by both wildlife and humans. Once it ripens and falls from the tree, persimmon is soft and sweet. If picked from the tree, this fruit can be green, very hard, gummy in texture and acidic. The seed count in persimmon is variable with some seedless varieties and some with as many as 10 seeds.

Persimmon trees, which grow 35 to 60 feet tall, are native to southern Indiana but can be found planted across the state. This species grows best in full sun and in moist, well-drained soils, but are tolerant of alkaline soil, clay, dry sites, and occasional drought. The natural range of the persimmon is the lower Midwest and southeastern United States reaching up into southern Illinois.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Persimmon, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

Hardwoods of the Central Midwest: Persimmon

ID That Tree: Persimmon

Morton Arboretum: Persimmon

Persimmons, The Education Store

Persimmon, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue Fort Wayne

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the Osage Orange or Maclura pomifera, also known as the hedge apple. While this species is not native to Indiana, it is found throughout the state, where it was planted for fence rows and fence post plantings due to its decay resistant wood.

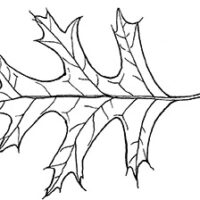

The leaves of Osage orange are oval shaped with pointed tips held alternately on slender twigs. The dark, glossy green leaves have smooth margins and no lobes. The twigs will often have sharp thorns more than half an inch long that are found where the leaves emerge and where the buds are located.

The bark of this species has a light gray surface with an orange undercoloring, which is distinctly furrowed and has a somewhat fibrous appearance. Osage orange is often multi-stemmed and spreads out over a large area.

The fruit of Osage orange, produced by female trees, also is a key identifying characteristic, as it resembles a large yellow-green-colored bumpy orange or a bumpy green apple. The fruit is four to six inch in diameter and has many folds, bumps and crevices, which has led to the description of it looking like a brain. Osage oranges have a sticky, milky sap on the inside.

Osage orange trees, which grow to 20 to 40 feet tall, are found in moist, well-drained soils, but are tolerant of alkaline soil, clay, dry sites, occasional drought and flooding. The natural range of the Osage orange is Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma and the region surrounding the Ozark mountains, although it has been planted in nearly every one of the lower 48 states.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Osage Orange, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

Fruit Like a Brain and Wood Like Steel – Got Nature article

You Say Hedge-Apple, I Say Osage Orange!, Indiana Yard and Garden – Purdue Consumer Horticulture.

Osage Orange, The Wood Database

Hardwoods of the Central Midwest: Osage orange

ID That Tree: Osage orange

Morton Arboretum: Osage orange

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the ninth and final of our featured oak varieties in Indiana, the Shingle Oak or Quercus imbricaria.

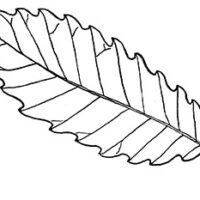

The leaves of shingle oak are oblong and have entire leaf margins, without lobes or teeth, unlike all other Indiana oaks. This species also retains its shiny, bristle-tipped leaves further into the winter than other oaks. The leaves turn from a dark green in the summer to yellow and brown in the fall.

The bark is dark gray and blocky, with long running ridges. Shingle oak tends to keep its lower dead limbs attached to the tree.

The fruit is a small, rounded acorn with a thin cap that covers a third to half of the acorn. The acorns turn dark in color before losing their caps, although some may drop off the tree with their caps in tact.

Shingle oaks, which grow to 50 to 60 feet tall and are found in moist, well-drained soil along streams and on hillsides, but can occasionally be found on dry sites. The natural range of the shingle oak is the midwestern United States, including the Appalachian mountain region, Ohio, and the central Mississippi River valley.

The Morton Arboretum states that shingle oak is fairly salt tolerant and tolerant of black walnut toxicity, and despite the fact that it has a taproot, this species can be easier to transplant than some other oaks.

Shingle oak, however, can be plagued with pests such as scale insects and two-lined chestnut borer. As with other oaks, the shingle oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt, which can be a potential disease problem.

Shingle oaks get their name, because traditionally the species was sectioned out and made into wood shingles.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Shingle Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Shingle Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Shingle Oak

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the eighth of our featured oak varieties in Indiana, the Pin Oak or Quercus palustris.

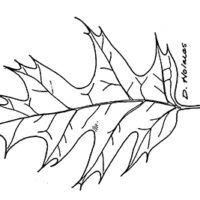

The leaves of pin oak are multi-lobed, with lobes coming out at nearly a 90-degree angle from the center of the leaves, and feature bristle tips like all members of the red/black oak family. On the pin oak, the alternately held leaves typically have less lobes than other members of the red/black oak group. In the fall, leaves change from medium green to a red to reddish brown color.

One key characteristic of pin oak are the branches, which angle downward especially on the lower part of the tree. The pin oak tends to keep its lower branches for a long period of time, which can create pin knots in the wood.

The trunk of pin oak is typically straight and single stemmed, while the bark is smooth and gray and may develop dark fissures with age.

The fruit is a rounded acorn with a relatively flat top with smooth scales, which covers only about one quarter of the nut.

Pin oaks, which grow to 60 to 70 feet tall and are relatively fast growing, are found mostly in moist to wet areas, such as streams, lakes and other wetlands, oftentimes in soils that have a medium to high acidity. Pin oaks also have been planted in many sites for landscape purposes.

The natural range of the pin oak is in bottomlands and imperfectly drained soils from New Jersey south to Virginia and west to Eastern Kansas and Oklahoma as well as south into North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas.

The Morton Arboretum states that pin oak suffers greatly from chlorosis or yellowing of the leaves in soils with high pH. As with other oaks, the pin oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt, which can be a potential disease problem along with oak blister.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Pin Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Pin Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Pin Oak

Pin Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue Fort Wayne

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

In 1978, Dan Cassens purchased a 10-acre plot of land close to the Purdue campus on which he planted a few Christmas trees as a side project. That plot of land developed into a family Christmas tree farm that Cassens and his wife Vicki have run for more than 40 years.

As the years passed, Dan, now a professor emeritus in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources after retiring in 2017 following a more than 40-year career at Purdue, enlisted the help of students within the department for both seasonal work and longer-term work on the farm and within his small lumber business.

What started as a few extra hands around the tree farm has turned into a hands-on learning opportunity for more than 20 FNR students each year, teaching workers skills from cutting and handling trees to customer service.

“I don’t remember how it got started; I guess I needed somebody to help me and I probably knew a couple of students that were anxious to work,” Cassens said. “I don’t know how many years it has been going on now, but it keeps getting bigger. Last year at Christmas time we had 20 some students helping us part time with the trees. It’s a good group because they have hard, physical work to do, but then they’ve also got time to sit and talk too.”

The work begins in October to prepare the tree farm for its opening on the Saturday before Thanksgiving, a date determined by customer demand over the years. Cassens Tree Farm has both choose-and-cut and pre-cut trees in species ranging from Canaan fir, Fraser fir and Concolor (White) fir to Scotch pine and white pine and Norway spruce. Once cut, trees have to be shook to remove dead needles, have a fresh cut on the butt of the tree to ensure they stand straight on a tree stand, and many get baled or wrapped, which condenses a tree, making it easier to handle and preventing damage to limbs that may occur in transit.

Cassens does not have prerequisite skills for students who work on the farm, save a willingness to work hard, although there are plenty of jobs on the tree farm that require specialized skills.

“We can use anybody that wants to work hard and has time available,” Cassens said. “We try to find out what their abilities are, because we do need people that can drive trucks and use chainsaws. Chainsaw experience is absolutely critical in part of the operation, but other than that, anybody can work in the barn. It doesn’t require much skill, just hard work. It’s hard to get it all sorted out with 20 students with different hours that they can work and different abilities, but we try to find out their abilities and schedules and try to get them placed. Once we get it going, it’s good.”

Daniel Warner, a 2011 alumnus in wood products manufacturing technology, said Cassens was very understanding when it came to lack of knowledge and miscues.

“My first day helping with the tree farm, I didn’t even know why we were planting these little pine trees (I was thinking lumber not Christmas),” Warner recalled. “I was also recruited for the mortar removal on several tons of vintage bricks. On one hatchet wielding, mortar removing day, I managed to get my truck stuck in Dan’s yard in the mud. Needless to say, the fact that we are still good friends shows that there was a great deal of forgiveness.”

Many of the students who work at Cassens farm are juniors or seniors, but some come back two or three years in a row once a part of the workforce, and often bring friends along to join the crew.

2018 forestry alumnus Ed Oehlman helped at Cassens Trees for five years, beginning the spring of his freshman year.

“I met Dan my freshman year at Purdue and that spring he invited me out to the farm to help him plant Christmas trees and that started my adventure,” Oehlman said. “I got the pleasure of seeing the whole process, from helping him plant trees, spending many hours mowing, sheering trees, spraying and treating trees, and lasting helping sell trees. Selling Christmas Trees is to this day one of the best jobs I’ve ever had. You couldn’t work for better people than Dan and Vicki. The days could be long and active, especially Thanksgiving weekend, but they always made sure you were taken care with little snacks or pizza, sometimes even home made soup. It made the time go by so quick, you’d just get started and before you knew it we were shutting up shop. The best was the fun little gamble we did at the end of the day to guess how many trees we had sold that day, which always made work fun! Working with and for Dan was a great learning experience, and not just about wood/lumber or Christmas trees. I learned so many great life and business skills!”

Charlie Warner, 2021 forestry alumnus and current master’s degree student, worked at Cassens Farm for three and a half years as an undergraduate student and has helped out five seasons overall after being introduced to Cassens and the job his freshman year thanks to Damon McGuckin (sustainable biomaterials 2018) and Oehlman.

“Both Ed and Damon worked for Dan at the tree farm throughout their time at Purdue and told me about him and how he was as both a boss and a professor,” Warner said. “Unfortunately, Dan retired from teaching before I had a chance to take his classes but I made up for it when I started working for him. I started working on the tree farm helping Dan with various jobs, whether it was sawing lumber with his Wood-Mizer, loading and unloading his dry kilns where he dried lumber, cutting down trees and bucking the logs to get them ready for the sawmill and many other jobs and mechanical work around the farm. I learned so much from my few years working for Dan. In fact, he was one of the strongest voices urging me to continue my studies and work towards a master’s degree. Not only did Dan teach me everything there is to know about the wood products industry and more, but he also taught me how to communicate with industry employers. He gave me the skills to make myself extremely marketable to a few of my internship opportunities. Furthermore, he taught me many life lessons.”

Additional Resources

Root Rot in Landscape Plants, The Education Store

Ask The Expert: Tree Inspection, Purdue Extension- FNR YouTube Channel

Ask The Expert: Tree Selection and Planting, Purdue Extension- FNR YouTube Channel

Surface Root Syndrome, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

The Nature of Teaching: Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Tree Appraisal and the Value of Trees, The Education Store

Construction and Trees: Guidelines for Protection, The Education Store

ID That Tree: Northern Red Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Northern Red Oak

Red Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Wild Bulletin, IN DNR Fish and Wildlife: Indiana hunters multiplied by all their harvest equals a lot of data. Keep track of DNR’s current harvest data and comparisons to previous seasons with our handy dashboard, which is updated daily throughout deer season. While the green bars indicate the season-to-date comparison to previous seasons, the blue bars illustrate the previous season counts after the current date. The numbers at the top show the harvest season totals.

DNR’s online game check-in system was first offered in 2012 and made the primary system in 2015. The preliminary data reported on this page from this system are updated once per day during deer hunting seasons. To view the data collected, please view the Indiana Deer Harvest data.

Resources:

Indiana Hunting & Trapping Guide, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN DNR), Fish & Wildlife

Indiana 2022-2023 Hunting & Trapping Season (pdf) list, IN DNR, Fish & Wildlife

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Trail Camera Tips and Tricks, Got Nature? Blog

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, Video, Purdue Extension Youtube channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 2, Hanging & Skinning, Video

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 3, Deboning, Video

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 4, Cutting, Grinding & Packaging, Video

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the sixth of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Northern Red Oak or Quercus rubra.

This native species is easily identified by its bark and its acorn. The bark looks like ski tracks or long running ridges that run up and down the sides of the tree, while the fruit is a large rounded acorn featuring a tight shallow cap with tight scales that resembles a beret sitting on top of a head.

Like other members of the red oak group, the leaves are multi-lobed and have bristle tips, including a sharp bristle tip on the terminal lobe. On the northern red oak, the alternately held leaves have veins that are palmate, or run out to the ends of the lobes from a single point in the middle. In the fall, the dark green leaves change to a bright red color.

The cluster of terminal buds at the end of northern red oak stems are smooth, shiny and reddish brown to brown in color. The twigs are somewhat angular in appearance.

Northern red oaks, which grow to 60 to 75 feet tall, are found mostly in upland areas. The natural range of northern red oak is the eastern United States and southern Canada, with the exception of the southern coastal plains. It grows well on moist, but well-drained soils.

The Morton Arboretum states that northern red oak has a high tolerance of salt and air pollution, making it a good tree for more exposed areas. This species prefers a well-drained, rich woodland site and it grows best in sandy, loam soil.

As with other oaks, the northern red oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. Galls and mites are common insect problems. This species can develop chlorosis symptoms in high pH soils.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Northern Red Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning, or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Northern Red Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Northern Red Oak

Red Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the seventh of our featured oak varieties in Indiana, the Black Oak or Quercus velutina.

The leaves of black oak are multi-lobed, typically with seven lobes, with deep sinuses in between, and have bristle tips like all members of the red/black oak family. On the black oak, the alternately held leaves can be extremely variable in shape, but the tops of the leaves are dark and shiny and have a leathery appearance. Leaves change from dark green in summer to yellow or yellow-brown in fall.

One key characteristic of black oak are the terminal buds, which are angular and fuzzy, very large and light tan. Alternately, the cluster of terminal buds at the end of northern red oak stems are smooth, shiny and reddish brown to brown in color.

The bark is very dark in color with narrow, blocky ridges, and lacks the silvery running ridges that are found on northern red oak.

The fruit is a small rounded acorn with striping running up and down the sides and a fuzzy coating along the outside edge. The cap is deeper than northern red oak and the scales on the edge of the cap resemble loose, rough shingles.

Black oaks, which grow to 50 to 60 feet tall, are found mostly in dry, upland areas. The natural range of the black oak is nearly all of the eastern United States, from Nebraska, Iowa and Oklahoma to the west, dipping south into Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and even a bit of the panhandle of Florida, extending along the eastern coastline, and northward into southern Ontario, Canada.

The Morton Arboretum states that black oak has a high tolerance of alkaline soils and dry sites, although it prefers acidic and dry soil. This species cannot withstand severe drought. It can also be difficult to transplant due to a deep taproot.

As with other oaks, the black oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt, which can be a potential disease problem. Galls on leaves caused by mites or insects are common, but not harmful.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Black Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Black Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Black Oak

Black Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the fifth of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Chinkapin Oak or Quercus muehlenbergii.

Also known as the Chinquapin Oak, the leaves of this species feature shallow, evenly lobed margins, but appear to have sharp-pointed teeth at the end resembling red or black oaks. This sharp point, however, is due to a gland at the end of the leaves, and there is no bristle tip as are typically found on red and black oaks. The shape of the leaves can be either broad like chestnut oak, or narrower.

Like other members of the white oak group, the bark of chinkapin oak is light gray and ashy, however it has a flaky appearance.

The fruit of the chinkapin oak is a small acorn that is dark brown or almost black in color. It has a cap that resembles a stocking cap, covering a third or half of the acorn, that features loose knobby scales. Under the cap, the acorn has a large white spot similar to that of a buckeye.

Chinkapin oaks, which grow to 50 to 80 feet tall, are found in both upland and bottomland areas. The natural range of chinkapin oak is the eastern United States, with the exception of the Atlantic coast and the immediate gulf coastal plains.

The Morton Arboretum states that chinkapin oak is best grown in rich, deep soils, but that it is often found in the wild on dry, limestone outcrops in low slopes and wooded hillsides. It notes that this species is one of the best oaks for alkaline soils. As with other oaks, this chinkapin oaks should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. This species also can be affected by anthracnose, oak wilt and two-lined chestnut borers.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Chinkapin Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning, or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Chinkapin Oak

ID That Tree: White Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: White Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Chinkapin Oak

Chinkapin Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the third of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Swamp White Oak or Quercus bicolor.

The swamp white oak has leaves with wavy, uneven lobed margins with blunt teeth, which are wider toward the tip than at the base. The alternately-held leaves are typically dark green on top with a silvery-white underside, which turn orange, gold and yellow in the fall.

The bark on swamp white oak is similar to that of white oak and often peels back especially on younger trees. Mature bark is dark gray-brown with flaky/shreddy bark or blocky ridges that are consistent up and down the tree.

The fruit of the swamp white oak is an acorn held on a long stalk, typically an inch or inch and a half long, called a peduncle.

Swamp white oaks, which grow to 50 to 60 feet tall, are named for the fact that they often grow in wet places, such as line drawing of swamp white oak acorns and peduncle. upland swamps and lowlands. This species also can tolerate well-drained upland sites, making it a good option for landscape plantings. The natural range of swamp white oak is the northern half of the eastern United States, reaching as far south as Missouri, southern Illinois and Kentucky, and north into Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The Morton Arboretum warns to plant swamp white oak in full sun and shares that the species is one of the easiest oaks to transplant and is more tolerant of poor drainage than other oaks. It also notes that oaks should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. Swamp white oak can be affected by pests such as anthracnose, powdery mildew, chlorosis in high pH soils, insect galls and oak wilt.

In general, lumber from the white oak group is among the heaviest next to hickory, weighing in at 47 pounds per cubic foot. It is very resistant to decay and is one of the best woods for steam bending.

White oak lumber has been used for a variety of purposes including log cabins, ships, wagon wheels and furniture. It also is preferred for indoor decorative applications ranging from furniture, especially in churches, to cabinets, interior trim, millwork and hardwood flooring and veneers. It also may be used for barrel making.

Its density and durability make white oak a favorite for industrial applications such as railroad ties, mine timbers, sill plates, fence posts and boards, pallets, and blocking, as well as industrial, agricultural and truck flooring.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Swamp White Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Swamp White Oak

ID That Tree: White Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: White Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Swamp White Oak

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- A Woodland Management Moment: Windbreak Around Walnut Plantings

Posted: March 3, 2026 in Forestry, Urban Forestry, Woodland Management Moment - Getting Certified as an Indiana Certified Prescribed Burn Manager

Posted: March 2, 2026 in How To, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Have You Seen a Soaring Eagle Lately? Morning Ag Clips

Posted: February 25, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Fragrant Sumac

Posted: February 4, 2026 in Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Tree Silvics and Succession Webinar: A Biological Basis for Management

Posted: January 30, 2026 in Forests and Street Trees, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Southwest Damage, Scalding or Frost Cracking

Posted: in Forestry, Urban Forestry - A Woodland Management Moment: Wide Spacing for Nut Production

Posted: January 29, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Woodland Management Moment, Woodlands - Woodsy Owl Edition for Educational Learning, USDA – U.S. Forest Service

Posted: January 21, 2026 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Trumpet Creeper

Posted: January 20, 2026 in Forests and Street Trees, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Indiana Woodland Steward Newsletter, The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment

Posted: January 7, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands