Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Trees and all forestlands are a major asset to our cities, towns, and communities. They work hard to provide aesthetic, functional and environmental benefits to improve the quality of life. A well-planted and maintained tree will grow faster and live longer than one improperly planted or maintained. Before planting your tree consider selection, placement, and maintenance to ensure an outcome that will meet your needs. This video will walk you through everything you need to know before you plant your tree.

Resources:

Tree Planting Part 1: Choosing a Tree, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Financial and Tax Aspect of Tree Planting, The Education Store

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife, The Education Store

Planning the Tree Planting Operation, The Education Store

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist,

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

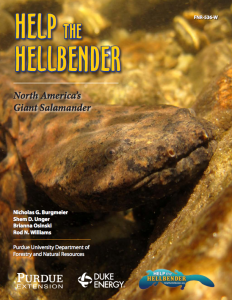

The eastern hellbender is a large, fully aquatic salamander that requires cool, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Because they require high-quality water and habitat, they are thought to be indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. While individuals may live up to 29 years, possibly longer, many populations of this unique salamander are in decline across their geographic range. It is the largest salamander in North America, found in and around rivers and streams in 17 states from New York to Missouri. Many hellbender populations are in decline within their geographic range. This publication provides information on identifying and preserving this important aquatic animal. You can find Help the Hellbender, FNR-536-W, as well as other great resources that can be found at The Purdue Education Store.

The eastern hellbender is a large, fully aquatic salamander that requires cool, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Because they require high-quality water and habitat, they are thought to be indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. While individuals may live up to 29 years, possibly longer, many populations of this unique salamander are in decline across their geographic range. It is the largest salamander in North America, found in and around rivers and streams in 17 states from New York to Missouri. Many hellbender populations are in decline within their geographic range. This publication provides information on identifying and preserving this important aquatic animal. You can find Help the Hellbender, FNR-536-W, as well as other great resources that can be found at The Purdue Education Store.

Resources:

How Anglers and Paddlers Can Help the Hellbender, The Education Store

Hellbender ID, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality by Protecting Sinkholes on Your Property, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality at Your Livestock Operation, The Education Store

Healthy Water, Happy Home – Lesson Plan, The Education Store

Nick Burgmeier, Research Biologist and Extension Wildlife Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dr. Rod Williams, Associate Head of Extension and Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Every hunter knows the importance of acorns for game and non-game species alike. When acorns are plentiful it can alter the movements and patterns of game species and when acorns are absent wildlife must rely on alternative food sources to meet their nutritional needs during the fall, winter, and early spring. Knowing the importance of acorns to many wildlife species, it is beneficial to identify which trees are the most reliable and best producing in the woods.

Intro to oaks

White oak acorns are clustered at the end of the branch – this year’s growth, like on this swamp white oak on the left. Whereas, red oak acorns are farther down the branch at the end of last year’s growth, like the northern red oak acorns on the right. (Photo by Brian MacGowan)

Oak trees in Indiana fall into 1 of 2 groups, white oak (e.g., white, swamp white, and chinkapin) or red oak (e.g., northern red, black, and pin). White oaks produce acorns in 1 growing season (acorns falling in 2016 are from flowers that were pollinated in the spring of 2016) and red oaks produce acorns in 2 growing seasons (acorns falling in 2016 are from flowers that were pollinated in the spring of 2015). This means a late frost in the spring may result in poor acorn production in white oaks in the fall of the same year, but will not influence red oak acorn production the same fall. However, a late frost in back-to-back years may result in a mast failure from both groups.

White oak acorns tend to be selected by wildlife more than red oak acorns because they contain less tannins resulting in a less bitter and more digestible acorn. Check out the Native Trees of the Midwest to learn more about oaks, their value for wildlife, and help you learn to identify different species.

Oak trees can be split into production groups based on their relative acorn production capabilities. Some individual oak trees are inherently poor producers and rarely produce acorns even in a bumper crop. Whereas other individuals are excellent producers and may produce acorns even in the poorest year. Research from the University of Tennessee reported poor mast producing trees represented 50% of white oaks in a stand and produced only 15% of the white oak acorn crop in a given year, whereas excellent producing trees represented 13% of white oaks, but produced 40% of the total white oak acorn production. When you included excellent and good producing white oaks together (31% of trees), they accounted for 67% of the total white oak acorn crop in a stand. This means a minority of the white oaks in a stand may produce a majority of the acorns!

Scouting oak trees

Understanding that some individual oak trees are poor producers, some are excellent, and some fall between poor and excellent, surveying oak trees can help identify important mast producing individuals. The late summer and early fall, just prior to or at the beginning of acorn drop, are perfect times to identify the best and worst producing oaks in your stand of timber. Scouting can be as formal as conducting a mast survey, National Deer Association, or as informal as taking mental notes of oak trees with heavy crops of acorns on the ground while you are walking to and from your tree stands in the fall. Either way, scouting oaks for acorn production capability can provide more information when determining where to hunt in the fall or which trees to retain and which trees to remove during a timber harvest. If wildlife management is an objective on your property, trees that you identify as the best acorn producers in the woods can be retained during a timber harvest, while poor producing trees can be removed with little detriment to overall acorn production. It is important to remember to retain a balance of oaks from both the red and white oak group, favoring red oak, to help safeguard against complete mast failures.

Forest management is insurance for mast failure

The top photo is of a mature forest with very few canopy gaps resulting in very little cover or food for wildlife. The bottom picture is of a forest stand where undesirable trees have been girdled (tree on the right-hand side of picture) to increase light to the forest floor and where multiple prescribed fire have been conducted to increase forage production and cover.

Annual acorn production in a stand of oaks is highly variably and can be dependent on environmental conditions. For example, late frosts, poor pollination, and insect infestations all can be culprits for poor mast production across a stand of oaks. Because of these factors, white oaks tend to only produce reliably 2 out of every 5 years, meaning 3 out of 5 years (60%) there is poor mast production or a failed mast crop in white oaks. Red oaks may produce a good crop as frequently as 2 to 5 years, but only produce a bumper crop an average every 5 to 7 years.

The extreme variability in acorn production underscores the importance in considering alternative food sources for fall, winter, and early spring for wildlife. In most mature forests with few canopy gaps there could be as little as 50-100 lbs of deer selected forage per acre in the understory. However, with some management, like thinning and prescribed fire the amount of deer selected forage can be increased to almost 1000 lbs/ac! Additionally, forest management also increases the amount cover throughout the year for species like white-tailed deer, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, woodcock, and many forest songbirds. Contrary to popular belief, cover can be more of a limiting factor for many wildlife species compared to food availability. Forest management could include girdling undesirable trees to expand growing space for mast producing trees or conducting a timber harvest removing undesirable trees and poor producing oak trees while retaining good producing trees. For more information on conducting a timber harvest for wildlife on your property contact a professional wildlife biologist or professional forester in your area.

When spending time in the woods this fall, take the time to look up and down to see which oaks in your woods are the best producers.

Resources:

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Masting Characteristics of White Oaks: Implications for Management, University of Tennessee

Wildlife Biologists, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Find a Forester, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Enrichment Planting of Oaks, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment: Indiana Forestry and Wildlife, The Education Store

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Choosing and planting a tree should be a well-informed and planned decision. Proper selection and planting can provide years of enjoyment for you and future generations as well as increased property value, improved environmental quality, and economic benefits. On the other hand, an inappropriate tree for your site or location can be a continual challenge and maintenance problem, or even a potential hazard, especially when there are utilities or other infrastructure nearby. This informative video will describe everything needed to know about choosing the right tree.

Resources:

Financial and Tax Aspect of Tree Planting, The Education Store

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife, The Education Store

Importance of Hardwood Tree Planting, The Education Store

Planning the Tree Planting Operation, The Education Store

Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

It’s a tough neighborhood for trees in the built environment. It is an ecosystem unlike any other, because it is dynamic, fragmented, high-pressure, and constantly under siege. There are continual extremes and challenges in this “un-natural” area as opposed to the environment in a more natural woodland. It’s a place where trees die young, without proper selection, planting, and care. Successful tree selection requires us to think backwards—beginning with the end in mind— to get the right tree in the right place…in the right way. This publication, Tree Selection for the “Un-natural” Environment, takes a look at some important components of the decision-making process for tree selection. There is both a publication and a video resource on this topic, both of which can be found below.

The video can be watched here:

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree

Resources:

Tree Selection for the “Un-natural” Environment, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Construction and Trees: Guidelines for Protection, The Education Store

Diseases in Hardwood Tree Plantings, The Education Store

The eastern hellbender is an endangered salamander found in the Blue River in southern Indiana. It requires cool, clean rivers and streams with high water quality in order to thrive. Water quality in the Blue River is affected by many factors. One relatively unknown contributor to poor water quality is pollution entering sinkholes. Many landowners have sinkholes on their properties and treat them like outdoor waste sites without knowing that these sinkholes have a direct link to our water supplies. In this video, Purdue biologists interview a local cave expert and a local conservationist about how sinkholes are connected to our rivers, streams, and water supplies and how we can help protect them.

Resources:

Improving Water Quality by Protecting Sinkholes on Your Property, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

A Landowner’s Guide to Sustainable Forestry: Part 5: Forests and Water, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm, The Education Store, YouTube

Animal Agriculture’s Effect on Water Quality: Pastures and Feedlots, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality At Your Livestock Operation, The Education Store, YouTube

Nick Burgmeier, Research Biologist & Extension Wildlife Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dr. Rod Williams, Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Human changes to the environment, like urbanization and climate change, have caused and will cause many wildlife extinctions. Efforts to conserve species occur all over the world, but not all species are seen as equal. In the animal conservation world, charismatic species play the lead roles in a show, while lesser-known or less-attractive species act as stage crew: we all know they are present, but we’re largely uncertain of what they do or how they play into the whole picture. As a result, we tend to see less conservation funding for these species.

Charismatic species are often large, fluffy, or cute: polar bears, narwhals, pandas, and koalas are excellent examples. They dominate news stories, children’s books, and most forms of media. In contrast, non-charismatic species are more difficult for humans to relate with: mussels, mice, and small fish fall into this category.

Societal bias towards charismatic species starts young: if you ask any child what their favorite animal is, chances are high that the species will be either cute and cuddly like a rabbits and foxes, or big and fearsome like bears or sharks. Chances are low that it will be a something slimy, small, or otherwise unattractive like a fish, reptile or bug.

Why is funding so low, or non-existing, for the not so furry, not so cute endangered species?

According to a study in the U.K., adults are more likely to donate money to causes represented by photos of charismatic species than non-charismatic species. This bias appeal results in the majority of research and conservation funding being dedicated to a small group of about 80 well-known, charismatic species. These species have what Dr. Hugh Possingham of the National Environmental Research Program (NERP) refers to as “donor appeal”. The remaining, non-charismatic species, tend to fall by the wayside, receive less funding and research interest. As a result, they tend to go extinct at higher rates. As Dr. Possingham says, “…if you’re an obscure animal or plant in a remote place, you have next to no hope of getting conservation resources.”

Results showing that the public are not excited to conserve non-charismatic wildlife is not surprising to Belyna Bentlage, a Purdue University outreach specialist, who specializes in research and outreach related to mussels. “People like to protect species that they feel they can relate to, that they can imagine owning as pets, like bear cubs or playful monkeys. It’s difficult to feel a connection to a hellbender or mussel. These animals don’t move as much, aren’t very interactive, and are not very cute. People just can’t relate to them in the same way as more charismatic species,” says Bentlage.

The lack of relate-ability of non-charismatics can spell disaster for many species. Belyna says, “When people don’t feel connected to a species, they won’t give money to fund research or protect the species. Lawmakers aren’t interested because the public isn’t interested, so it’s left up to researchers. So little is known about the ecological role of many of these species, that it’s difficult for researchers to justify why they should be studied. With the competitive funding climate in research, less charismatic species loose out.”

With a tight funding climate, uninterested lawmakers, and a fickle, how can we protect these threatened non-charismatic species?

One solution might just be in making non-charismatic species charismatic. Outreach coordinators like Belyna Bentlage are working cooperatively with biologists to change the way humans perceive of slimy, spiny, gross or otherwise unattractive species.

The project Belyna works on, with Purdue FNR Professor Linda Prokopy and Associate Professor Rod Williams gives super-hero personalities to non-charismatic mussels. Each mussel species has a special power that reflects something about its innate characteristics, like the snuffbox and clubshell mussel images shared in this blog.

“Making these animals more relatable and fun allows both children and adults to better understand their importance. People consciously pick their favorites, compare the drawings, and then get excited when they see these species in the wild. It creates a public that is really interested in protecting the species,” Bentlage explained.

Erin Kenison, a PhD student at Purdue University, has helped use similar tactics to promote conservation of hellbenders. The poorly named species is actually a giant salamander that used to inhabit all Indiana rivers, but is now restricted to the Blue River giant salamander that used to inhabit all Indiana rivers, but is now restricted to the Blue River.

The large, green, slimy creature is aptly nicknamed “old lasagna sides” because of its flappy skin that bunches at its sides. The Help the Hellbender project uses costumes, cartoons, coloring pages and games to generate public attention for the species.

“Historically, its been believed that hellbenders had evil powers and could even cause the death of babies,” says Kenison. “Making the hellbender more relatable dismantles a lot of these beliefs, making it more likely that river-users won’t try to harm them.”

Are we willing to learn more about the non-charismatic species and help with conservation efforts?

While there are many challenges for the conservation of non-charismatic species, Belyna Bentlage also says that the public’s lack of familiarity with these species may be a strength. “When people don’t know much, they are often willing to learn and adapt their actions. They are not as set in their ways, so it’s more likely that we can introduce new behaviors to protect a species. Overall, people generally want to help threatened species, not hurt them.”

Non- charismatic wildlife, as slimy or spiny or unattractive as they may be, are an important part of the natural ecosystem. Next time you see a mussel, hellbender, or similar creature, take a photo, but leave it be. These species need your help and support to survive, even if their beauty is mainly on the inside.

If you would like to find out how you can help or learn more about these endangered species, see the resources listed below:

Help the Hellbender

DNR: Nature Preserves: Endangered Threatened & Rare Species, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Zoe Glas, Graduate Research Assistant

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Question: We want to plant five fastigiata (upright blue spruce) in an area with heavily compacted soil with large percentage of clay content in the soil. The soil essentially feels and handles like play dough. Water cannot drain down in the soil because of the high clay content. Ewes were planted but they are dying since they are sitting in clay soil with water standing around the roots. A swimming pool was built nearby three years ago and the equipment used was rolled over this area numerous times to remove soil for the pool area, and the clay soil is heavily compacted and won’t allow water to drain. We are thinking we will dig out the soil maybe five feet deep, 10 feet wide, and 20 feet deep and replace it with good compost top soil mix. We are not sure if we need a T drain or not. We want to plant five of the upright blue spruce in this area. Do you have an arborist you can suggest to come out and look at our situation?

Answer: This is a typical issue with soils in our area being composed of primarily clay which leads to heavy, poorly drained soils. The fact that there has been a great deal of construction damage worsens the problem even further. Traffic of this magnitude can render landscape sites virtually useless for any type of sustainable tree planting without mitigation. Your ideas of creating an adjusted planting space may not correct the problem completely, but may help alleviate the damage and improve planting conditions.

I am not certain that digging up and replacing the soil would be of much value, long term. I have had success with site improvements, but it isn’t guaranteed. It may provide temporary improvements to get the trees established, however, once they mature and outgrow your “prepared planting space”, the troubles could begin. Once the roots try to expand into the compacted, native soils, most likely they would be redirected back into the pit, minimizing good root spread for health and stability. Additionally, you would be creating a “bathtub effect” with poor drainage in your excavated pit.

I am not certain that digging up and replacing the soil would be of much value, long term. I have had success with site improvements, but it isn’t guaranteed. It may provide temporary improvements to get the trees established, however, once they mature and outgrow your “prepared planting space”, the troubles could begin. Once the roots try to expand into the compacted, native soils, most likely they would be redirected back into the pit, minimizing good root spread for health and stability. Additionally, you would be creating a “bathtub effect” with poor drainage in your excavated pit.

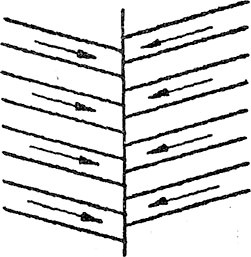

It may be possible to remove and replace the soils in that excavated area with lateral drainage at the bottom of the planting area to remove the water and prevent prolonged exposure to wetness on the root system. Perforated tiles draining outside of the planting area may work. Create a single, central line with a herringbone lateral system that goes past the dimensions of the pit. Use good topsoil with no amendments to the new planting area. One other consideration would be roots clogging the drainage system if not set deep enough. Again, this is a stretch for mitigation, but may be successful with proper preparation.

I would suggest contacting a company with an ISA certified arborist who can assist you with the process. Use Trees Are Good’s Arborist Search to help locate an arborist in your area. Also, try reviewing the publications on construction damage for some corrective and preventative treatments for the future.

Resources:

Collecting Soil Samples for Testing, The Education Store

Soil and Water Conservation Districts, Indiana State Department of Agriculture

Certified Soil Testing Laboratories, Purdue Department of Agronomy/Extension

Arborist Search – Trees Are Good

Tree Installation: Process and Practices – The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Mechanical Damage to Trees: Mowing and Maintenance Equipment – The Education Store

Why Is My Tree Dying? – The Education Store

Tree Risk Management – The Education Store

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Paddling and fishing are great ways to enjoy our rivers and streams. However, these seemingly harmless activities can actually be harmful to the eastern hellbender and other aquatic wildlife if the proper precautions are not followed.

Paddling and fishing are great ways to enjoy our rivers and streams. However, these seemingly harmless activities can actually be harmful to the eastern hellbender and other aquatic wildlife if the proper precautions are not followed.

In this video, Purdue videographer Aaron Doenges speaks with Tom Waters and Ranger Bob Sawtelle, two professionals around Indiana’s Blue River, to learn more about safe ways to paddle and fish. By following a few simple tips, paddlers and anglers can still enjoy these aquatic activities without harming the local wildlife.

If we all do our part to help the hellbender, this at-risk species can survive and grow. Anglers and paddlers aren’t the only people that can help. Farmers can also check out the video Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm to learn healthy farming practices to improve water quality for the hellbender and other aquatic wildlife, and landowners are encouraged to check out Improving Water Quality At Your Livestock Operation to learn about how to manage livestock without polluting nearby rivers and streams.

To stay current with the latest news and research on the eastern hellbender, please visit the Help the Hellbender website.

Resources:

How Anglers and Paddlers Can Help the Hellbender – The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm – The Education Store

Improving Water Quality At Your Livestock Operation – The Education Store

Eastern Hellbender ID Video – The Education Store

Help the Hellbender – Purdue Extension

Rod Williams, Associate Head of Extension and Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Hellbenders have been rapidly declining since the 1980s due to various factors, including poor water quality. Poor water quality is caused by a variety of ecological issues, one of which is land use along the river. Farmers can reduce the impact of their farming practices on water quality using a number of different management practices.

Hellbenders have been rapidly declining since the 1980s due to various factors, including poor water quality. Poor water quality is caused by a variety of ecological issues, one of which is land use along the river. Farmers can reduce the impact of their farming practices on water quality using a number of different management practices.

In this new video “Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm,” we focus on how farmers can use management practices on their farm that improves water quality while still meeting their production goals. Todd Armstrong, a farmer on the Blue River, uses cover crops and no till farming to reduce soil erosion and describes the ecological and economic benefits to these practices in this video.

Please visit the Help the Hellbender website for more information regarding other management practices that improve water quality, and also check out the National Resource Conservation Services website (NRCS) for news and other information related to soil and resource conservation.

Resources:

Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm – The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Options for Farmers – Help the Hellbender

Water Quality – National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS)

Managing Cover Crops: An Introduction to Integrating Cover Crops Into a Corn-Soybean Rotation – The Education Store

Adoption of Agricultural Conservation Practices: Insights from Research and Practice – The Education Store

Megan Kuechle, Undergraduate Extension Intern

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dr. Rod Williams, Associate Head of FNR Extension and Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- Purdue Extension: Empowering Indiana Through Innovation, Education and Community Impact

Posted: January 28, 2026 in Community Development, How To, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Natural Resource Planning, Woodlands - Forest Landowners: Share Your Experience with Regeneration and Restoration

Posted: January 27, 2026 in Forestry, How To, Timber Marketing, Woodlands - It’s Not Too Late to Order Trees for Spring Planting

Posted: January 13, 2026 in Forestry, How To, Plants - Now Is The Time To Control Non-Native Bush Honeysuckle

Posted: October 30, 2025 in Forestry, How To, Invasive Plant Species, Woodlands - October Is Firewood Month: Protect Indiana’s Forests by Making Smart Choices

Posted: October 13, 2025 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - ID That Tree: Smooth Sumac

Posted: October 2, 2025 in Forestry, How To, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Wild Grape Vine

Posted: August 12, 2025 in Forestry, How To, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Publication – Sericea Lespedeza Control

Posted: July 7, 2025 in Forestry, How To, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - How to ID Asian Jumping Worms, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: July 2, 2025 in How To, Invasive Insects, Wildlife - Alert – Water Your Trees, Watch Video

Posted: June 20, 2025 in Alert, Drought, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands