Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Once aquatic invasive species (AIS) are established in a new environment, typically, they are difficult or impossible to remove. Even if they are removed, their impacts are often irreversible. It is much more environmentally and economically sound to prevent the introduction of new AIS through thoughtful purchasing and proper care of organisms. Check out Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant’s web page the Aquatic Invasive Species and find resources for teachers, water garden hobbyists, aquatic landscaping designers and to aquatic enthusiasts. The video titled Beauty Contained: Preventing Invasive Species from Escaping Water Gardens is also available which contains guidelines that were adopted from the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council and the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force along with addressing the care and selection of plants and animals for water gardens.

Resources:

Aquatic Invaders in the Marketplace, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Great Lakes Sea Grant Network (GLERL), NOAA – Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

Indiana Bans 28 Invasive Aquatic Plants, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG), Newsroom

A Field Guide to Fish Invaders of the Great Lake Regions, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Purdue Researchers Get to the Bottom of Another Quagga Mussel Impact, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Protect Your Waters, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service & U.S. Coast Guard

Clean Boat Programs, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension

Quagga mussels, which arrived in Lake Michigan in the 1990s via ballast water discharged from ships, have colonized vast expanses of the Lake Michigan bottom, reaching densities as high as roughly 35,000 quagga mussels per square meter. The invasive species that can have major economic impacts filters up to 4 liters of water per day, and so far seems unaffected by any means of population control. It is also a constant threat to other systems, as it is readily transported between water bodies.

Quagga mussels, which arrived in Lake Michigan in the 1990s via ballast water discharged from ships, have colonized vast expanses of the Lake Michigan bottom, reaching densities as high as roughly 35,000 quagga mussels per square meter. The invasive species that can have major economic impacts filters up to 4 liters of water per day, and so far seems unaffected by any means of population control. It is also a constant threat to other systems, as it is readily transported between water bodies.

Researchers have long known that these voracious filter feeders impact water quality in the lake, but their influence on water movement had remained largely a mystery.

“Although Lake Michigan is already infested with these mussels, an accurate filtration model would be imperative for determining the fate of substances like nutrients and plankton in the water,” Purdue University PhD candidate David Cannon said. “In other quagga mussel-threatened systems, like Lake Mead, this could be used to determine the potential impact of mussels on the lake, which could in turn be used to develop policy and push for funding to keep mussels out of the lakes.”

For full article and video view Purdue Researchers Get to the Bottom of Another Quagga Mussel Impact.

Resources:

A Field Guide to Fish Invaders of the Great Lake Regions, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Protect Your Waters, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service & U.S. Coast Guard

Profitability of Hybrid Striped Bass Cage Aquaculture in the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

A Guide to Marketing for Small-Scale Aquaculture Producers, The Education Store

Aquaculture Industry in Indiana Growing, Purdue Today

Sustainable Aquaculture: What does it mean to you?, The Education Store

Pond and Wildlife Management website, Purdue Extension

Fish Cleaning with Purdue Extension County Extension Director, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Aquaponics: What to consider before starting your business, YouTube, Purdue Ag Economics

Aquatics & Fisheries, Playlist, YouTube, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

University of Illinois Extension and Purdue University Extension

The Forest Pest Outreach and Survey Project at Purdue reminds us that early detection is the best way to slow the spread of invasive species. You can report invasive species by calling the Invasive Species hotline at 1-866-NO-EXOTIC (1-866-663-9684) or using the free Great Lakes Early Detection Network smartphone app, which can be downloaded on iTunes or Google Play. View video to see how easy it is to use the app, Great Lakes Early Detection Network App (GLEDN).

The Forest Pest Outreach and Survey Project at Purdue reminds us that early detection is the best way to slow the spread of invasive species. You can report invasive species by calling the Invasive Species hotline at 1-866-NO-EXOTIC (1-866-663-9684) or using the free Great Lakes Early Detection Network smartphone app, which can be downloaded on iTunes or Google Play. View video to see how easy it is to use the app, Great Lakes Early Detection Network App (GLEDN).

If you’re interested in learning more about invasive pests and how to report them, sign up for one of our free Early Detector Training workshops!

National Invasive Species Awareness Week: February 27-March 3, 2017.

Resources:

Invasive Species – Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Ask an Expert – Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Indiana Invasive Species Council – Includes: IDNR, Purdue Department of Entomology and Professional Partners

Invasive Species Week a reminder to watch for destructive pests, Purdue entomologist says – Purdue Agriculture News

Sara Stack, MS student

Purdue Department of Entomology

Lesions from bovine Tb infection in the chest cavity of a wild white-tailed deer. Photo by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Bovine tuberculosis (bovine Tb) is an on-going issue in Indiana’s wild white-tailed deer herd. Bovine Tb was first discovered in wild deer in Indiana in August 2016 near a bovine Tb positive cattle farm in Franklin County. Since August 2017, Indiana Department of Natural Resources and the Board of Animal Health have been monitoring and managing the bovine Tb situation. A second cattle farm in Franklin County tested positive for bovine Tb in December 2016, but no hunter harvested deer have tested positive for bovine Tb during the 2016 deer season. The IDNR will continue to monitor and manage the bovine Tb situation according to a departmental management plan. View the following web page to find more information, Bovine Tb in Wild White-Tailed Deer: Background and Frequently Asked Questions.

Resources:

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

How to Build a Plastic Mesh Deer Exclusion Fence, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Indiana Deer Hunting, Biology and Management, and Safe Food Handling and Preparation, IDNR

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Description of Bovine Tuberculosis:

Bovine tuberculosis (bovine Tb) is a disease found in mammals caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis). In North America, bovine Tb is most commonly found in domestic cattle and captive and wild cervids (white-tailed deer, elk, etc.) and less commonly in other mammals such as raccoon, opossums, coyotes, and wild boars.

Bovine Tb has been greatly reduced in the cattle industry since the National Cooperative State-Federal Bovine Tuberculosis eradication program began in 1917. Currently, most states are accredited as “Bovine Tuberculosis-Free” by the United States Department of Agriculture, however, sporadic outbreaks do still occur throughout the United States.

Cattle, captive cervids, and wild white-tailed deer are considered reservoir hosts for bovine Tb. A reservoir host is a species in which bovine Tb can persist and be transmitted among individuals within a species or be transmitted to another species. Wild white-tailed deer may pose the greatest threat to the establishment of bovine Tb on the landscape because they move freely across the landscape and may contact multiple domestic cattle herds.

In Indiana, bovine Tb was detected in domestic cattle in 2008, 2010, and 2011 and most recently in April 2016 and a captive red deer and elk herd in Franklin County in 2009. The first case of bovine Tb in a wild white-tailed deer in Indiana occurred in August 2016 in Franklin County. All confirmed cases of bovine Tb in Indiana have been from the same strain of M. Bovis.

As of Dec 14th, 2016, 2,024 white-tailed deer samples have been collected, 2 exhibited lesions consistent with bovine Tb; 1,897 samples have been tested and 0 samples have tested positive for bovine Tb.

Frequently asked questions:

Yes, bovine Tb is transmissible to humans but bovine Tb accounts for <2% of tuberculosis cases in the United States. Most cases of bovine Tb in humans are caused by consuming unpasteurized dairy products and the likelihood of contracting bovine Tb from a wild deer is minuscule. There has been only one confirmed case of transmission of bovine Tb to a human from an infected white-tailed deer. In that case, bovine Tb was thought to be transmitted via bodily fluids from the infected deer contacting an open wound on the person during the field dressing process.

Both Michigan and Minnesota have had outbreaks of bovine Tb in wild white-tailed deer. Currently, bovine Tb occurs in less than 2% of deer in the Bovine Tb Management Zone in Michigan and has not been detected since 2009 in a wild deer in Minnesota. There are certainly lessons to be learned from both states and those lessons are being incorporated in the management of bovine Tb in Indiana.

Human health is the main concern; given that bovine Tb is transmissible to humans. Additionally, bovine Tb is not a naturally occurring disease in white-tailed deer. Deer can also be a reservoir for bovine Tb potentially transmitting bovine Tb to uninfected deer and also to uninfected cattle through direct contact or through shared feeding. Because deer are free-ranging they have the potential to contact multiple cattle herds and transmit bovine Tb across the landscape. If bovine Tb is maintained in the wild deer herd, Indiana is at risk of losing the “Bovine Tuberculosis-Free” accreditation from the USDA, which has negative economic impacts for the cattle industry in Indiana.

An animal infected with bovine Tb can shed the M. bovis bacteria through repertory secretions, feces, urine, or unpasteurized milk. Under the right environmental conditions, the bacteria can remain viable in the environment for months. The disease is spread when an uninfected animal comes into direct contact with secretions of an infected animal or indirectly through an M. bovis contaminated source in the environment (e.g. feed pile). Deer can contract bovine Tb through direct contact with an infected animal, either another deer or cattle or through sharing feeding with an infected animal at wildlife supplemental feeding piles or areas where cattle are fed or cattle feed is stored. Deer can transmit bovine Tb in the same ways as contracting the disease. Indirect contact, by means of shared feeding, is believed to be the primary pathway between deer and cattle.

Both Michigan and Minnesota have followed the same general approach to eradicating bovine Tb. Their approach consisted of (1) reducing deer density in the bovine Tb management zone, (2) eliminating baiting and supplemental feeding of wildlife, and (3) continual monitoring for bovine Tb in wild deer.

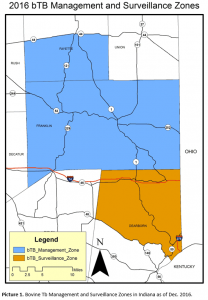

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and Indiana Board of Animal Health (BOAH) are considering similar steps as in Michigan and Minnesota to eliminate bovine Tb in wild deer in Indiana. First, a bovine Tb Management Zone has been established in Franklin County and southern Fayette County and a Bovine Tb Surveillance Zone has been established in Dearborn County (Picture 1). In the management and surveillance zones, the IDNR sampled >2,000 hunter harvested deer during the 2016 deer season – none of which tested positive for bovine Tb. As a result, the IDNR determined active population reduction through sharp shooting (as used in other states) is not warranted at this time. The IDNR is still allowing landowners in the management zone to request disease permit to control deer near cattle farms in an effort to reduce cattle and deer interactions. Also, feeding deer or any wildlife is banned in the management zone. Management and surveillance will continue into the future. More information on the management of bovine Tb in Indiana can be found on the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)-Bovine Tb Surveillance and Management and the Indiana State Board of Animal Health (BOAH)-Bovine Tuberculosis.

Reducing deer density is important to eliminate bovine Tb because the disease is density-dependent and spreads more efficiently in areas with high deer densities. In densely populated areas, deer come into contact with other wild deer, captive cervids, and cattle herds more frequently, thus potentially spreading bovine Tb to uninfected animals. The purpose of deer reductions is to reduce the risk of transmission by reducing population density, removing diseased deer, and to estimate the percentage of the population with bovine Tb.

One of the primary routes in which bovine Tb can be spread is through shared feeding. This is because supplemental feeding artificially concentrates deer in a very small area increasing contact among deer and other wildlife species. Additionally, M. bovis can survive for months on a supplemental feed pile. Thus, banning supplemental feeding is a critical step to limit the contact of infected and uninfected animals.

To date, there are no effective treatments for bovine Tb in wild white-tailed deer. This is why practices such as deer density reduction, a ban on supplemental feeding, and continued surveillance are vital in combating bovine Tb in wild deer.

Picture 2. Lesions from bovine Tb infection in the chest cavity of a wild white-tailed deer. Photo by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

The clinical signs of bovine Tb recognizable to hunters would be small to large white, tan, or yellow lesions on the lungs, rib cage, or in the chest cavity (Picture 2). However, in Michigan only 64% of deer exhibited lesions and only 42% would have been recognizable to hunters. If you harvest a deer in the bovine Tb management or surveillance zone, you should submit it for sampling. After submitting you can search for the bovine Tb test results of your submission by going to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources – IDNR’s bovine Tb management website and clicking the “Look up the results of a deer you submitted” link.

Check the IDNR’s Bovine Tb website for information on submitting harvested deer for sampling.

Venison from deer harvested within the Bovine Tb Management and Surveillance Zone should be cooked to an internal temperature of 165 degrees Fahrenheit to kill M. bovis and other bacteria. Bovine Tb is rarely present on muscle tissue (meat) and the most likely way bovine Tb would be on meat would be through contamination from secretions within the body cavity.

Bovine Tb may be transmitted through bodily secretions of an infected deer contacting an exposed wound on a person during the field dressing process. If lesions consistent with bovine Tb are found inside a harvested deer you should contact the IDNR and submit the deer for testing. It’s important to mention that the likelihood of contracting bovine Tb from wild deer is very rare, but there are some steps you can take to further minimize the risk.

*Always wear gloves when field dressing, skinning, and processing a deer because bovine Tb may be present in fluids from the internal body cavity.

* Make sure to clean knives that are used for field dressing thoroughly prior to using them to skin or process a deer, or use different knives for each step.

* Thoroughly wash your hands after field dressing, skinning, and processing deer.

* Cook all venison to an internal temperature of 165 degrees Fahrenheit.

Cattle operators in the Bovine Tb Management and Surveillance Area should limit contact between deer and cattle or cattle feed by:* Only feed cattle an amount that can be consumed in one day

* Fence areas where cattle feed is stored

* Store feed away from deer

* Close the end of large plastic bags used to store corn, haylage, or silage and also remove any feed from the ground around the ends of the bag

* Use hunting and additional landowner permits from the IDNR as a management tool to reduce deer density around your farm

If you own land in the Bovine Tb Management Zone (Picture 1) you should contact Joe Caudell (812) 334-1137, the Indiana State Deer Biologist, or the Indiana Bovine Tb Hotline at (844) 803-0002.

Additional Bovine Tb Resources:

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, FNR-551-W publication, Purdue Extension – Forestry & Natural Resources

Bovine Tb, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Bovine Tb, Indiana State Board of Animal Health (BOAH)

Bovine Tb Disease, USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Bovine Tb, Michigan Department of Natural Resources

Bovine Tb, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Bovine Tb factsheet, Center for Disease Control

Information provided by: Jarred Brooke, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Extension’s Don’t be a Zombie exhibit is traveling the country to illustrate the need to prepare for emergencies. It urges people to be ready for an emergency and have a plan. Don’t Wait. Communicate. Make an Emergency Communication Plan for you and your family because you just don’t know when disasters will impact your community. At the Indiana State Fair, almost 60,000 visitors got a chance to check out the Don’t be a Zombie – Be Prepared exhibit, complete with zombies, interactive displays, maze, and even a video game made to simulate a zombie apocalypse!

Purdue Extension’s Don’t be a Zombie exhibit is traveling the country to illustrate the need to prepare for emergencies. It urges people to be ready for an emergency and have a plan. Don’t Wait. Communicate. Make an Emergency Communication Plan for you and your family because you just don’t know when disasters will impact your community. At the Indiana State Fair, almost 60,000 visitors got a chance to check out the Don’t be a Zombie – Be Prepared exhibit, complete with zombies, interactive displays, maze, and even a video game made to simulate a zombie apocalypse!

The display aims to have its viewers take away four main points:

- Be informed – know what threats may affect your community

- Make a family emergency plan – a plan for everyone and everything in case of disaster

- Make a 72-hour emergency kit – enough supplies for everyone involved, along with first-aid, a crank radio, and a gallon of water per person each day

- Practice and maintain these plans regularly – a plan is only good if it is up to date and known by everyone

The Don’t Be a Zombie exhibit is currently travelling to museums all over the country, its existence thanks to the collaboration between Purdue Extension and EDEN, a prime source for disaster preparedness information.

Resources:

Purdue Agriculture Traveling Exhibit Program

First Steps to Flood Recovery, The Education Store

Keeping Food Safe During Emergencies, The Education Store

Purdue Traveling Exhibit Program

Genetically Modified Organisms, or GMOs, is a topic that continues to be in the news and yet many of us know relatively little about this topic. We want to know what we’re eating, and we want to know how this topic is impacting the environment. Knowing more equips us to make the best decisions for ourselves and generations to come. That’s why The Science of GMOs website was created, to help break down the information and address some of the most important questions and concerns that many have. You can always count on this site to address this complicated and evolving issue with neutral, scientifically sound information.

Genetically Modified Organisms, or GMOs, is a topic that continues to be in the news and yet many of us know relatively little about this topic. We want to know what we’re eating, and we want to know how this topic is impacting the environment. Knowing more equips us to make the best decisions for ourselves and generations to come. That’s why The Science of GMOs website was created, to help break down the information and address some of the most important questions and concerns that many have. You can always count on this site to address this complicated and evolving issue with neutral, scientifically sound information.

Submit a question by visiting The Science of GMOs website: https://ag.purdue.edu/GMOs.

Resources:

GMO Issues Facing Indiana Farmers in 2001, The Education Store

Grain Quality Issues Related to Genetically Modified Crops, The Education Store

Field Crops: Corn Insect Control Recommendations – 2015, The Education Store

Indiana Vegetable Planting Calendar, The Education Store

Photo by: James Gathany, Center for Disease Control and Prevention

You may have likely heard of the Zika virus at this point – a new infection on the rise that is drawing many parallels to the West Nile virus that caused 286 deaths in the United States in 2012. Like the West Nile, Zika was first discovered over sixty years ago and wasn’t considered to be a large concern until it reemerged unexpectedly years later. Both viruses are carried by mosquitos, and 80% of people infected display no symptoms and are at risk of unwittingly further spreading the infection. And most importantly, both viruses have no current treatment or vaccination and can be deadly.

When discussing the Zika virus, it is important to know that currently there have been no cases of infection in the continental U.S. While this means there is no need to immediately panic, transmission of diseases are often unpredictable as human population and global travel increase. Zika appeared in Brazil last May and has quickly spread to over 20 countries across Central and South America, causing the World Health Organization to declare the virus an international public health emergency, predicting that Zika could infect as many as 4 million people by the end of this year. With that ominous prediction looming over us, a good precaution to take is knowing how the mosquitos potentially carrying the virus can be controlled and avoided.

Simply avoiding mosquitos is an effective first step. Staying indoors during the daytime when mosquitos feed can help lessen exposure to mosquitos, as well as wearing long sleeves, pants, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-approved mosquito repellant when going outdoors.

Another preventative measure you can take is eliminating potential mosquito breeding sites from your area. Mosquitos breed in containers of standing water, and getting rid of them can reduce mosquito population in your area. Dog bowls, birdbaths, potted plants, and similar objects are all potential breeding grounds, and removing them means less places for mosquito eggs to hatch.

Again, the Zika virus isn’t currently an immediate concern for people in the United States, but this information is crucial to know as scientists learn more about how this virus is spread. At any rate, they’re also give good tips for avoiding annoying mosquito bites! To learn more, please check out the Purdue University Agriculture News article “Controlling and avoiding mosquitos helps minimize risk of Zika.”

Resources:

Controlling and avoiding mosquitos helps minimize risk of Zika – Purdue University Agriculture News

Zika virus and mosquito-borne disease experts – Purdue University News

Mosquitos – Purdue University Medical Entomology

Zika Virus – World Health Organization

Management of Ponds, Wetlands, and Other Water Reservoirs to Minimize Mosquitos – The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Aaron Doenges, videographer & assistant web designer

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) trees also known as Maidenhair trees are slow-growing, relatively pest-free, wind-pollinated trees that can be found in all fifty of the contiguous United States. The only tree species within division Ginkgophyta to escape extinction, Ginkgo biloba is known as an ancient tree with prehistoric fossils dating back 270 million years found on every continent except Antarctica and Australia.

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) trees also known as Maidenhair trees are slow-growing, relatively pest-free, wind-pollinated trees that can be found in all fifty of the contiguous United States. The only tree species within division Ginkgophyta to escape extinction, Ginkgo biloba is known as an ancient tree with prehistoric fossils dating back 270 million years found on every continent except Antarctica and Australia.

Ginkgo grow best in full sunlight and can reach heights greater than 35 m (115 ft). Ginkgo trees are valuable street trees because of their low susceptibility to smoke, drought, or low temperatures. These trees grow slowly and perform relatively well in most soil types provided they are well-drained. The leaves turn a vibrant yellow during autumn but drop soon after its brilliant fall color is observed.

Unfortunately, in late autumn, the dirty secret that female ginkgo trees hide is revealed. The “fruit” produced by female ginkgo trees is foul smelling (has been compared to rancid butter or animal excrement) and is cast in the fall following the first frost. Though immature when cast, the embryos within the fruit continue to mature on the ground for up to two months afterwards. This means that anyone unfortunate enough to step on the fruit during that time is exposed to its pungent odor.

Extreme caution should be used when selecting ginkgo trees for landscape ornamentals or for street trees since there is no way to discern a male from a female at the seedling stage. Several “Boys Only” cultivars have been developed such as ‘Autumn Gold’ or ‘Lakeview’ to ensure that you do not end up with a  stinky yard or street when the trees begin to fruit. While the scent of the seed coat may be undesirable, the seed kernel is highly valued in Eastern Asia as a food product. In the United States, herbal extracts composed of ginkgo leaves are believed to improve short-term memory and concentration.

stinky yard or street when the trees begin to fruit. While the scent of the seed coat may be undesirable, the seed kernel is highly valued in Eastern Asia as a food product. In the United States, herbal extracts composed of ginkgo leaves are believed to improve short-term memory and concentration.

On the campus of Purdue University several ginkgo trees can be found although unfortunately for students the vast majority of these are female and the scent of crushed seed pods often follows many students to class on the bottoms of their shoes. A word of warning, the ginkgo trees planted near Pfendler Hall, Forestry, and the Cordova Center are all females. Watch your step this winter and this is the one rare example of when boys ARE better than girls.

Resources:

Ginkgo biloba – Purdue Arboretum Explorer

Ginkgo – Encyclopedia.com

Ginkgo biloba L. – USDA Forest Service

Shaneka Lawson, Plant Physiologist & Adjunct Assistant Professor

Purdue University Department of Natural Resources

Photo credit: Pedro Tenorio-Lezama, Bugwood.org

Made infamous through the trial of Socrates, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Macbeth, and several other works of classic literature, poison hemlock is an extremely toxic plant that will pose a risk this summer and should be handled with caution.

Poison hemlock is a biennial plant, meaning that it has a two year lifespan. Last summer, it went through vegetative growth and largely stayed out of sight. This summer, it will produce small white clusters of flowers and will be more likely to catch the attention of animals and people. Poison hemlock is a member of the parsley family and can sometimes be confused with wild carrot. However, its distinguishing feature is its hairless hollow stalks with purple blotches. If you see these, be careful!

The biggest risk with poison hemlock is ingestion. Lethal doses are fairly small, so it is important for animal owners or parents of young children to identify it in their area and remove it if possible. The toxins can also be absorbed through the skin and lungs, so be sure to wear gloves and a mask when handling these plants.

Symptoms of hemlock poisoning include dilation of the pupils, weakening or slowing pulse, blue coloration around the mouth and eventually paralysis of the central nervous system and muscles leading to death. Quick treatment can reverse the effects, so act quickly.

Resources

Invasive Plant Species Fact Sheets: Poison Hemlock, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Recognizing and Managing Poison Hemlock, Purdue Landscape Report

Poison Hemlock, Pest & Crop Newsletter, Purdue Extension – Entomology

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Distribution Update, Purdue Landscape Report

What are Invasive Species and Why Should I Care?, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Report INvasive, Purdue Extension & Indiana Invasive Species Council

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

Recent Posts

- Alert – Water Your Trees, Watch Video

Posted: June 20, 2025 in Alert, Drought, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - IN DNR Deer Updates – Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Detected in Several Areas in Indiana

Posted: October 16, 2024 in Alert, Disease, Forestry, How To, Wildlife, Woodlands - 2024 Turkey Brood Count Wants your Observations – MyDNR

Posted: June 28, 2024 in Alert, Community Development, Wildlife - Spongy Moth in Spring Time – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: June 3, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Invasive Insects, Urban Forestry - MyDNR – First positive case of chronic wasting disease in Indiana

Posted: April 29, 2024 in Alert, Disease, How To, Safety, Wildlife - Report Spotted Lanternfly – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 10, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, Invasive Insects, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Declining Pines of the White Variety – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: in Alert, Disease, Forestry, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Are you seeing nests of our state endangered swan? – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 9, 2024 in Alert, Forestry, How To, Wildlife - 2024-25 Fishing Guide now available – Wild Bulletin

Posted: April 4, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, How To, Ponds, Wildlife - Look Out for Invasive Carp in Your Bait Bucket – Wild Bulletin

Posted: March 31, 2024 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Invasive Animal Species, Wildlife

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands