Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

This exotic invasive tree species is commonly found in Indiana landscape, callery pear. Callery pear has been planted as an ornamental tree in the midwest for decades. The original selection bradford pear was actually infertile and would not spread from seed but additional varieties have been planted and have crossed with the original Bradford and those are producing fertile seed. Find out how the seed spreads and what we can do to help our forest.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel (Invasive White Mulberry, Siberian Elm, Tree of Heaven)

Invasive Species Playlist, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Asian Bush Honeysuckle, Burning Bush, Callery Pear, Multiflora rose)

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Against Invasives, Garlic Mustard, Autumn Olive)

Woodland Stewardship for Landowners, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel (Common Buckthorn, Japanese Barberry)

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

The GLEDN Phone App – Great Lakes Early Detection Network

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (Report Invasives)

How long do seeds of the invasive tree, Ailanthus altissima remain viable? (Invasive Tree of Heaven), USDA Forest Service

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Aquatic Invasive Species, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG)

Episode 11 – Exploring the challenges of Invasive Species, Habitat University-Natural Resource University

What are invasive species and why should I care?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – FNR

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center

Purdue Department of Forestry & Natural Resources

A rain garden is a green infrastructure project that can improve the quality of stormwater, minimize pollution, and enhance biodiversity and pollinator habitat. Purdue, Iowa State and Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant researchers explain how to site, size, design, install and maintain a rain garden, and provide advice on plant selection, too.

When stormwater runs off streets, driveways, roofs, and other impervious surfaces, it can move pollutants such as oil, fertilizers, heat, and chemicals to storm drains and eventually to natural bodies of water, such as lakes, streams, and rivers. These natural water sources are valuable resources for recreation, irrigation, and drinking water. Green infrastructure projects, such as rain gardens, can improve the quality of stormwater, reduce flooding, minimize pollution, enhance biodiversity and pollinator habitat, and create educational and recreational opportunities.

Green infrastructure includes a range of practices that allows stormwater to infiltrate into the soil or be stored for later use, thereby reducing flows to sewer systems and surface waters (U.S. EPA, 2022). A rain garden is one such practice. It is a small-scale landscape feature planted with native shrubs, perennial plants, or flowers in a shallow depression. It captures and stores runoff, allowing it to slowly infiltrate into the soil. At the property scale and when properly located, rain gardens lessen erosion in steeply sloped areas, reduce the potential for water to flow into basements, and minimize ponding in areas with poor drainage. The net effect of multiple green infrastructure practices can reduce streambank erosion and downstream flooding as stream flows decrease. Water quality is also affected as plants and microbes in the soil filter nutrients and some heavy metals as the stormwater soaks into the soil.

To receive the free download for the Introduction to Rain Garden Design please visit The Education Store.

Resources:

Community Development, Purdue Extension Program

Environmental Planning in Community Plans, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Enhancing the Value of Public Spaces: Creating Healthy Communities, The Education Store

Conservation through Community Leadership, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Planting Forest Trees and Shrubs in Indiana, The Education Store

Planting Your Tree Part 1: Choosing Your Tree, Video, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Subscribe – Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources Calendar, workshops and Conferences

Kara A Salazar, Sustainable Communities

Purdue Community Development Extension Specialist

Sara Winnike McMillan, Associate Professor

Purdue University

Payton Ginestra, Natural Resources and Environmental Science

Purdue University

Laura Esman, Water Quality Program Coordinator

Purdue University

John Orick, Purdue Extension Master Gardener State Coordinator

Purdue University

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the Jack pine, or Pinus banksiana.

This conifer, also known as scrub pine, has clusters of two dark green needles, which are one to one and a half inches long, noticeably curved or arched like a bow and slightly twisted.

Bark on the jack pine is dark to medium gray, thin and flaky when young and features thick plates in older trees. This tree growth irregularly and can produce between one and three whorls of side branches annually. It tends to have a much lighter crown than white pine or the spruces.

The cones of jack pine are one to three inches long and remain closed while on the tree unless disturbed by a heat event such as fire. The cones may also be curved and twisted into many irregular shapes and tend to stay on the tree for many years.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Jack Pine, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Jack Pine

Morton Arboretum: Jack Pine

Jack Pine, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue Fort Wayne

Borers of Pines and Other Needle Bearing Evergreens in Landscapes, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Managing the Zimmerman Pine Moth, The Education Store

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the scotch pine, or Pinus sylvestris, which is not native to Indiana, but has been widely planted in the state for Christmas tree production.

This conifer, also known as Scots pine, has clusters of two blue green or yellow green needles, which are one to three inches long and do not break when bent.

Bark on the scotch pine is light gray on the outside and orange in color on the inner bark, but it is not flaky like red pine. Bark on the lower end of the trunk is dark and blocky, while the upper bark is more orange.

On the tree, cones are cylindrical and pointed at the ends, approximately three inches long and do not have spines at the end of the scales. Cones become more egg shaped as the scales begin to open up once off the tree.

Scotch pine, which grows to between 25 and 60 feet tall, is typically found on acidic, moist, well-drained soil. It prefers full sun and has some drought tolerance. The species’ native range is Scotland, Scandinavia, northern Europe and northern Asia. According to the U.S. Forest Service database, It has been introduced across the United States and Canada and is naturalized in the Northeast and in the Great Lakes states.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Scotch Pine, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Scotch Pine

Morton Arboretum: Scotch Pine

A Choose-and-Cut Pine and Fir Christmas Tree Case Study

Diplodia Tip Blight of Two-Needle Pines, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Borers of Pines and Other Needle Bearing Evergreens in Landscapes, The Education Store

America’s Least Wanted Wood-Borers, Japanese Pine Sawyer, The Education Store

Managing the Zimmerman Pine Moth, The Education Store

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Landscape Report: There have been a number of samples we have received at the PPDL in recent weeks that bear similar problems worth noting. It is still relatively early for significant in-season disease development due to how cold it has been, although we have certainly had enough rainfall to encourage fungal growth. We have received multiple samples of spruce and boxwood which will be covered.

Since the start of the year, we have been received spruce samples showing needle thinning, browning, and loss in the lower canopy (Fig 1, 2, 3). If I said these are Colorado Blue Spruce, we could call it Rhizosphaera and maybe call it a day, however, these samples are primarily from other species of spruce. An important thing to remember when it comes to evergreen conifers is that it takes time for symptoms to develop, whether due to disease or to abiotic factors. The majority of these branches lacked any discoloration within, suggesting that there was no infection and that the limbs were still living.

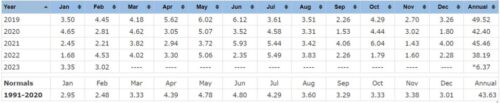

Last year, we had drought conditions during the summer throughout large parts of the state leading into the fall with below average precipitation (Fig 4). Since evergreen plants hold onto their foliage through the winter, desiccation can occur since they are still losing water to the air, especially when it is dry and windy. If these plants are not getting enough water going into winter, there is greater risk of winter injury or burn and needles may turn brown, especially near branch tips (exposed areas).

Irrigation during periods of hot and dry weather will mitigate drought stress, but irrigation may still be necessary in the fall to avoid needle desiccation. What about when trees of the same age, on the same property are showing different levels of severity or one tree is perfectly fine while the next is toast?

I think it is important to remember each tree is an individual. We may see similar patterns in the landscape across the same tree species when stress is caused by environmental effects, but if the overall health of that tree when it was first planted, the amount of love and care, and the site conditions (soil, light, general water levels) are different, then the trees may have vastly different reactions to stress. Determining this 5 years after planting can be difficult for someone just walking into the situation, or when dealing with 30ft tall trees, but it is something we have to keep in mind.

For more images and full article view: Early Season Samples: Spruce Needle Loss and Boxwood Leaf Spots

Subscribe and receive the newsletter: Purdue Landscape Report Newsletter.

Resources:

The Purdue Landscape Report

Purdue Landscape Report Facebook Page

Find an Arborist website, Trees are Good, International Society of Arboriculture (ISA)

Equipment Damage to Trees, Got Nature? Blog

Tree wounds and healing, Got Nature? Blog

Tree Defect Identification, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Tree Pruning Essentials, Publication & Video, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Why Is My Tree Dying?, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Channel

John Bonkowski, Plant Disease Diagnostician

Departments of Botany & Plant Pathology

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the red pine, or Pinus resinosa, which is not native to Indiana, but has been planted widely across the state.

This conifer has clusters of two slender, flexible, green or yellow green needles, which are four to six inches long. If the needles are bent, they will break cleanly, unlike that of ornamentally planted Austrian pine. The long needles cause a very tufted look to the tree canopy.

Bark on the red pine is scaly and red-orange in color in younger trees and platy and reddish brown in older trees. Cones are egg-shaped, approximately two inches long and have smooth scales.

Red pine tends to be very, straight and tall, growing to between 50 and 80 feet tall. This species, which can be as tall as 200 feet, is typically found on sandy, well-drained soils with low pH and full sun. The natural range of the red pine is the northeastern United States and southern Canada near the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. The species can be found as far west as Minnesota and into Manitoba. It can be found dipping south into Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to IN Trees: Red Pine, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Red Pine

Morton Arboretum: Red Pine

Diplodia Tip Blight of Two-Needle Pines, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Borers of Pines and Other Needle Bearing Evergreens in Landscapes, The Education Store

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Figure 1. Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index for winter 2022-2023 in the United States from the Midwest Regional Climate Center.

Purdue Landscape Report: Remember the pre-Christmas freeze? What about the extremely long fall? The Midwest experienced above-average temperatures through most of the winter, but those extremely cold temps in late December made for more than a few pipes to freeze in the southern part of the Midwest. The dichotomy in weather patterns over the last several years has been mind-boggling. We’ve gone from flooding to drought in most recent growing seasons, to the extremes in temperatures this winter. Though it’s an inconvenience for us, plants don’t have the option of heated seats or umbrellas, thus stress or death can occur in these extremes.

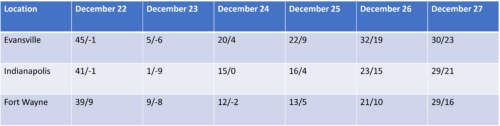

East of the Mississippi River, the 2022-2023 winter has been significantly milder than average, based on past climate models (Fig. 1). We don’t typically have cold injury in late December, but drastic changes in temperatures can cause pernicious effects on plant health. The entire state of Indiana had the drastic changes in temperature December 22-27, 2022 (Table 1).

Table 1. The high and low temperatures (F) in Evansville, Indianapolis, and Fort Wayne December 22-27, 2022. Data courtesy of the National Weather Service.

There’s on-going evidence of damage across the Midwest from the late/long fall and extreme cold that was experienced in mid-late December. We’ve observed some perennial evergreens, i.e., American holly, Meserve holly (Fig. 2), and skip laurel (Fig. 3), damaged or killed during this winter, especially in the southern parts of the Midwest. In addition, some deciduous trees have significant bark cracking (Fig. 4). Though these plants are hardy well below the temperatures that were experienced, the maximum dormancy wasn’t yet reached by plants due to the warm temperatures so late into the winter season.

Figure 2. A planting of Meserve hollies died during the winter of 2022-2023 due to cold injury. Photo via Gabriel Gluesenkamp.

There’s on-going evidence of damage across the Midwest from the late/long fall and extreme cold that was experienced in mid-late December. We’ve observed some perennial evergreens, i.e., American holly, Meserve holly (Fig. 2), and skip laurel (Fig. 3), damaged or killed during this winter, especially in the southern parts of the Midwest. In addition, some deciduous trees have significant bark cracking (Fig. 4). Though these plants are hardy well below the temperatures that were experienced, the maximum dormancy wasn’t yet reached by plants due to the warm temperatures so late into the winter season.

Plants survive through the winter by entering a phase of dormancy in which the plant is in a state of suspended animation. The dormancy process in plants is a complicated series of internal events caused by external events, that allow perennial plants to protect themselves during environmental changes, such as winter.

For more images and full article view: Cold Injury During a Very Mild Winter?

Resources:

The Purdue Landscape Report

Purdue Landscape Report Facebook Page

Fall webworms: Should you manage them, Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Landscape Report Team Begins New Virtual Series, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR)

Tree wounds and healing, Got Nature? Blog

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Why Is My Tree Dying?, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Kyle Daniel, Commercial Landscape and Nursery Crops Extension Specialist

Purdue Horticulture & Landscape Architecture

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet Eastern red cedar or Juniperus virginiana, one of the most common coniferous trees in Indiana.

This evergreen tree, also known as aromatic cedar, is unique in that it has both scale-like and sharp-pointed leaves. The foliage can be soft to the touch on mature trees or be quite sharp in seedlings and younger trees. The foliage turns from green to blueish green in spring to red or brown in winter.

The red cedar features a shreddy bark on both the trunk and branches, which is gray brown in color. It is slow growing but may live longer than 450 years.

The fruit of red cedar is a small cone, which resembles and is often referred to as a berry, that is blue in color and features a whitish bloom on the surface. The fruit is preferred by birds and wildlife of many varieties and is thus spread to roadsides, old pastures and other locations with plenty of sun and disturbed soil. It can be found in forest understories, but prefers direct sunlight.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Eastern Red Cedar, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Eastern Red Cedar

Morton Arboretum: Eastern Red Cedar

Fruit Diseases: Cedar Apple and Related Rusts on Apples in the Home Landscape

Diseases of Landscape Plants: Cedar Apple and Related Rusts on Landscape Plants

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Eastern Redcedar, Purdue Fort Wayne

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we meet the eastern white pine or Pinus strobus, which historically was one of the tallest trees in the eastern United States.

This conifer is the only five-needled pine native to Indiana, meaning that the bundles of needles coming off the branches in one location, also called fascicles, include five needles per bundle. These needles are typically between two and four inches long and are blue green in color. Needles remain on the tree for two to three years before dropping in the fall.

The bark on younger trees is dark and relatively smooth, and becomes quite furrowed in older trees. The eastern white pine adds a ring of side branches and a terminal shoot yearly with age.

The cones of this species are up to eight inches long, have relatively thin scales and are often covered with quite a bit of white sap or pitch. Cones remain on the tree for two years.

Eastern white pine trees typically grow to between 65 and 100 feet tall, but can exceed 150 feet tall in old growth forests. This species prefers acidic, moist and well-drained soil, but can tolerate alkaline soils. Eastern white pine is native to the central and eastern United States and Canada. Its range extends as far west as Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa and Minnesota in the U.S. and Manitoba in Canada. Its distribution reaches south through the Great Lakes states and in the Appalachian Mountains into northern Georgia as well as east along the Atlantic seaboard.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Eastern White Pine, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Eastern White Pine

Morton Arboretum: Eastern White Pine

Tree Diseases: White Pine Decline in Indiana

White Pine and Salt Tolerance

U.S. Forest Service Database – Eastern White Pine

Purdue Arboretum Explorer

The Woody Plant Seed Manual, U.S. Forest Service

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Extension Forester

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

While earthworms in the spring are a happy sight for gardeners, an invasive worm species is wreaking havoc for landowners and gardeners in southern Indiana.

Robert Bruner, Purdue Extension’s exotic forest pest specialist, describes jumping worms, an invasive species to North America in the genus Amynthas: “Traditionally, when we see earthworms, they are deep in the ground and a little slimy. The jumping worms are a little bit bigger, kind of dry and scaly, and tend to thrash around much like a snake does.”

While worms have a reputation as a helpful species found in the soil ecosystem, invasive jumping worms do not live up to that standard, Bruner explained. Jumping worms will consume all organic material from the top layer of soil, leaving behind a coffee ground-like waste with no nutrients for plants or seeds.

Since jumping worms stay within the first few inches of topsoil, they are not creating channels for water and air the way earthworms do, disrupting water flow to plant roots.

“So basically, they’re just very nasty pests that ruin the quality of our soil, and the only thing that can really grow in soil like that are essentially invasive plants, or species that are meant to survive really harsh conditions,” Bruner said.

Currently, the worms are being found in cities around southern Indiana, he said, particularly in Terre Haute. There is still much to learn about jumping worms, making eradication efforts difficult. One thing that is known, Bruner said, is they aren’t a migrating species.

“This is the kind of invasive pest that is moved almost entirely through human activity. They don’t crawl superfast,” he explained. “So, when they move, that means they’re moving because we’re transferring soil, say, from someone’s plants or someone’s compost and we’re bringing them to a new area.”

Any invasive species sightings should be reported to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources at depp@dnr.in.gov or by calling 1-866-663-9684.

For full article with additional photos view: Gardeners asked to be vigilant this spring for invasive jumping worms, Purdue College of Agriculture News.

Other Resources:

Fall webworms: Should you manage them?, Purdue Landscape Report

Mimosa Webworm, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Sod Webworms, Turf Science at Purdue University

Bagworm caterpillars are out feeding, be ready to spray your trees, Purdue Extension Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Got Nature? Blog

Purdue Plant Doctor App Suite, Purdue Extension-Entomology

Landscape & Ornamentals: Bagworms, The Education Store

What are invasive species and why should I care? (How to report invasives.), Purdue Extension – FNR Got Nature? Blog

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Report Invasive Species, Purdue Invasive Species

The GLEDN Phone App – Great Lakes Early Detection Network

EDDMaps – Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System

Indiana Department of Natural Resources: Invasive Species

Indiana Invasive Species Council

Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA)

Ask An Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources

Jillian Ellison, Agricultural Communication

Purdue College of Agriculture

Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator

Purdue Department of Entomology

Recent Posts

- ID That Tree: Fragrant Sumac

Posted: February 4, 2026 in Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - It’s Not Too Late to Order Trees for Spring Planting

Posted: January 13, 2026 in Forestry, How To, Plants - Red in Winter – What Are Those Red Fruits I See?

Posted: December 1, 2025 in Forestry, Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Untangling and Identifying Vines, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: September 29, 2025 in Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Wildlife - Control Management of Poison Hemlock

Posted: May 7, 2025 in Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - Top 10 Spring Flowering Shrubs, Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: April 28, 2025 in Gardening, Plants, Urban Forestry - PPDL’s 2024 Annual Report – Enhancing Plant Health

Posted: March 21, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Insects, Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Wildlife - What Are Invasive Species and Why Should I Care?

Posted: February 24, 2025 in Forestry, How To, Invasive Plant Species, Plants, Woodlands - Ask An Expert: Holidays in the Wild

Posted: December 9, 2024 in Christmas Trees, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, How To, Plants, Wildlife, Woodlands - When Roundup Isn’t Roundup – Purdue Landscape Report

Posted: October 17, 2024 in Forestry, Gardening, Plants, Urban Forestry

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands