Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

A new educational exhibit aimed for kindergartners to fifth graders called “A Salamander Tale” is ready to be shipped around the country and spread amphibian awareness. This interactive attraction is roughly 300 square feet and helps educate visitors at all ages about hellbenders, other salamanders and amphibians in general. Built into the exhibit is a video game called “Hellbender Havoc,” which provides a fun and unique way to learn about hellbenders. “Hellbender Havoc” is also playable online using Chrome or Firefox browsers.

A new educational exhibit aimed for kindergartners to fifth graders called “A Salamander Tale” is ready to be shipped around the country and spread amphibian awareness. This interactive attraction is roughly 300 square feet and helps educate visitors at all ages about hellbenders, other salamanders and amphibians in general. Built into the exhibit is a video game called “Hellbender Havoc,” which provides a fun and unique way to learn about hellbenders. “Hellbender Havoc” is also playable online using Chrome or Firefox browsers.

Rental fees do apply for reserving the exhibit. Indiana state and extension professionals, also including Purdue staff, can rent the exhibit for free after paying for shipping. For more information, please check out the Salamander Tale web page, or feel free to take a look at other current exhibits on the Purdue Traveling Exhibits page. Check out Herbie the Hellbender today and inspire the Herpetologists of tomorrow!

Resources

Purdue Traveling Exhibits, Purdue Agriculture

Help the Hellbender, Purdue Extension

Salamanders of Indiana Book, The Education Store

The idea of 10,000 honey bees swarming is a very, very unsettling thought for many people. This sounds like a dangerous and maybe even deadly situation, but in reality, it usually isn’t. Large swarms of honey bees are actually fairly common and completely harmless unless provoked.

The idea of 10,000 honey bees swarming is a very, very unsettling thought for many people. This sounds like a dangerous and maybe even deadly situation, but in reality, it usually isn’t. Large swarms of honey bees are actually fairly common and completely harmless unless provoked.

As a colony of honey bees grows, sooner or later it outgrows its hive, and it is time to spread out and create a new one. This process starts with the production of new queens. They are grown in special chambers and are fed a diet of “royal jelly” as they grow. When the first one emerges from its chamber fully developed, it kills the others to eliminate the competition.

This new queen leaves the hive in search of “drone zones,” areas where male honey bee drones congregate in hopes to mate with the queen. After a successful mating, the queen returns to the hive, signaling the worker bees of the colony to begin preparing for swarming. Some fly from the hive to explore and search for possible new locations for a new hive. Meanwhile, others start reducing the old queen’s diet, slimming her down in preparation for the swarming. When the new queen begins laying eggs, it is officially time to swarm.

The older bees escort the old queen out of the hive in a massive swarm towards the location scouted out previously to begin a new colony. However, sometimes when a suitable location hasn’t been found in time, the swarm lands on the ground, protecting the queen in the center until one can be found. While probably terrifying to someone with a fear of bees, there is no reason to be alarmed. These bees are focused on protecting the queen and won’t leave the cluster or sting anyone unless provoked. Eventually, when a location is found, the cluster swarms to it and starts a new colony.

So if you encounter a huge group of honey bees, don’t panic. While they might look intimidating, these bees are busy transitioning to a new colony and don’t pose a hazard to anyone.

Resources

Swarms Hanging Around, Purdue Extension

Indiana Honey Bee Swarms, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Tom Turpin, Professor, Insect Outreach, Instruction Development Specialist

Department of Entomology, Purdue University

The next big step in the initiative to save the hellbenders of Indiana was completed on May 18, 2015, as three hellbenders were transferred from Purdue University’s Aquaculture Research Lab to the Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette. This is the last of 50 hellbenders transferred from the lab to Columbian Park Zoo, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo and Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville.

The next big step in the initiative to save the hellbenders of Indiana was completed on May 18, 2015, as three hellbenders were transferred from Purdue University’s Aquaculture Research Lab to the Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette. This is the last of 50 hellbenders transferred from the lab to Columbian Park Zoo, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo and Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville.

In 2013, Associate Professor of Wildlife Science Rod Williams and his team collected 300 eggs from the Blue River in Southern Indiana. These eggs grew into young hellbenders in the lab and were transferred to the three zoos to continue growing to adulthood. In the wild, hellbender mortality rate is extremely high, as high as 99%. The salamanders are at their most vulnerable state during their juvenile years, and being raised in captivity will greatly improve their chances of survival when they are released back into the wild in a couple years.

Once released, the hellbenders will be tracked via radio transmitters to monitor their movements, habitat preferences and survivorship. The last group of 18 hellbenders released into the wild had a 22.5% survival rate after one year, and Williams hopes to improve on that. A group of 80 more hellbenders will be released in 2016 with 130 in the following year. Williams’ goal of 40-50% survival rate would mark huge progress in saving the hellbenders of Indiana.

Resources

Help the Hellbender, Purdue Extension

The Nature of Teaching: Adaptations for Aquatic Amphibians, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

How Our Zoos Help Hellbenders, The Education Store

Hellbenders Rock!, The Education Store

Help the Hellbender, North America’s Giant Salamander, The Education Store

How Anglers and Paddlers Can Help the Hellbender, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Video

Subscribe to Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Channel

Rod Williams, Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

When you rush to the closet to grab your favorite shorts and T-shirt, remember that you are not the only creature looking forward to the warmer weather. It is important to check yourself or have a buddy check you for passengers when you get back from the field to lessen the likelihood of bringing ticks home with you.

Indiana has 15 tick species, but the three listed below are the most prevalent.

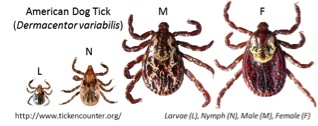

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis): Found primarily along trails, walkways or in fields, American Dog ticks are rarely found in forests. Despite their name, these ticks feed on a multitude of hosts in addition to the family pet and can transmit Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, a potentially fatal disease contracted by 32 people in Indiana last year. The American Dog Tick also carries Tularemia, a rare but dangerous disease that is often misdiagnosed for the flu.

American Dog ticks can survive for two years at any stage in life until a suitable host is found. Male ticks mate with the female while she is feeding as after she is sated, she drops off of the host and lays 4,000+ eggs before dying. Larval ticks only feed for three to four days from a host before molting into nymphs. The nymph feeds on a variety of small/medium-sized hosts before dropping to the leaf litter and molting into adults. Interestingly, these ticks are least likely to bite humans.

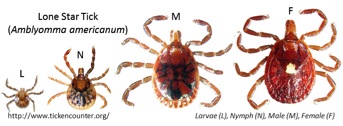

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum): Found primarily in dense underbrush and forested areas. As with the American Dog Tick, these ticks are capable of transmitting Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in addition to Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, another tickborne disease that presents with symptoms similar to the flu but was confirmed in 49 Indiana cases in 2013. ‘Stari’ (Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness) Borreliosis is a tick-vectored disease that presents with a large round or elliptical rash and flu symptoms transmitted by the Lone Star Tick.

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum): Found primarily in dense underbrush and forested areas. As with the American Dog Tick, these ticks are capable of transmitting Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in addition to Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, another tickborne disease that presents with symptoms similar to the flu but was confirmed in 49 Indiana cases in 2013. ‘Stari’ (Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness) Borreliosis is a tick-vectored disease that presents with a large round or elliptical rash and flu symptoms transmitted by the Lone Star Tick.

Voracious eaters, adult Lone Star ticks often take human hosts or other large mammals. After a week, the female is capable of laying 3,000+ eggs. The larval Lone Star ticks only feed for four days before detaching, burying themselves in leaf litter and molting into nymphs. Able to quickly ascend up pant legs, these nymphs can be firmly attached to a host in < 10 minutes. After five days, the nymphs detach and molt into adults.

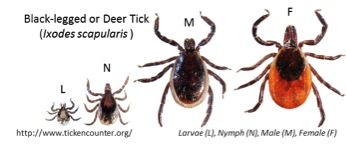

Black-legged or Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis): Found primarily in deciduous forests, these ticks predominantly use white-tailed deer or other large mammals as hosts. Unlike the relatively accelerated life cycles of the American Dog and Lone Star ticks, the Deer Tick life cycle takes nearly two years to complete.

Deer ticks are most notorious for spreading Lyme disease, a dangerous disease that causes flu-like symptoms that, if left untreated, can spread to joints and compromise the nervous system. More than 100 cases of Lyme disease were confirmed in Indiana in 2013. Babesiosis is caused by microscopic parasites that infect red blood cells, and Anaplasmosis is caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Both of these diseases are transmitted through the bite of an infected Deer Tick.

Only the female Deer Tick feeds, and once completely engorged, they lay an egg mass of 1,900+ eggs before dying in late-May. Deer Tick larvae and nymphs remain in the moist leaf litter within forested areas and prefer smaller hosts. After feeding for three days in each developmental stage, they burrow into the litter to molt. Larvae emerge as nymphs in spring, and nymphs emerge as adults in fall.

The table here illustrates the months of activity for the larval, nymph, male and female tick life cycle stages which gives you a quick reference for Indiana. This information was gathered from the resources listed in this post.

The table here illustrates the months of activity for the larval, nymph, male and female tick life cycle stages which gives you a quick reference for Indiana. This information was gathered from the resources listed in this post.

Indiana ticks can carry several diseases, but the three most common are Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Lyme Disease and Ehrlichiosis. Symptoms of all three diseases range from spreading rashes, headaches, fatigue, fevers and muscle aches. Likelihood of infection is rare; however, instances of each disease are increasing in Indiana.

Be careful and try not to pick up eight-legged hitchhikers. If you suspect that you have been bitten by a tick or develop a rash along with flu symptoms, contact your local health department for a disease screening.

Resources

Ticks, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Ticks, Medical Entomology, Purdue University

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Tularemia, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Lyme Disease, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Ehrlichiosis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Parasites – Babesiosis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Anaplasmosis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

‘Stari’ Borreliosis, Columbia University Medical Center

tickencounter.org, Tick Encounter Resource Center, University of Rhode Island

Shaneka Lawson, Adjunct Assistant Professor

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (INDNR) has just released a new and updated application for iPhone and Android users. A successor to the previous app released in March 2011, this iteration introduces new features, and DNR Director Cameron Clark calls it a “portable field guide.” The free app contains helpful information about any DNR related properties like forests, wildlife areas and state parks and serves as a helpful companion while planning outdoor activities. To download this app, visit iTunes for iPhone users or Google Play Store for Android users.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (INDNR) has just released a new and updated application for iPhone and Android users. A successor to the previous app released in March 2011, this iteration introduces new features, and DNR Director Cameron Clark calls it a “portable field guide.” The free app contains helpful information about any DNR related properties like forests, wildlife areas and state parks and serves as a helpful companion while planning outdoor activities. To download this app, visit iTunes for iPhone users or Google Play Store for Android users.

Resources

Indiana DNR Smartphone Apps, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

DNR Releases New, Improved Mobile Apps, WANE15

Publications and Maps, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Ever been to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula? I had the opportunity to go (first time visiting Michigan, yay!), and to make it even more awesome, I got the chance to touch yearling black bear cubs. Through Purdue’s Student Chapter of The Wildlife Society, some students had the chance to go to Crystal Falls, Michigan, to shadow Mississippi State graduate students with a project they were working on concerning white-tailed deer. So of course I went. What else am I going to do on a random weekend in February?

We arrived in Michigan eight hours later with plenty of snow on the ground and the temperature already near the negatives. We met up with the graduates Sunday, and they explained to us the purpose of their project: looking into the population decline of white-tailed deer. In order to fully analyze the decline, the project needed to look into the role of predators, winter weather, habitat and the condition and reproduction of deer in order to understand the aspects affecting the population.

So what does this entail? Well first, we hiked through the deep snow in the woods to reach bobcat hair snares to collect any fur, feathers or hair found on thin, spiky coils of wire. The sites were baited with a deer rib cage or beaver which attracted a variety of visitors including bobcats, wolves, coyotes, martens, fishers, hawks, owls, chickadees, snowshoe hares and even flying squirrels. By collecting the hair or feathers caught in the snares, the graduates could collect data using the DNA from the samples. It’s amazing how much you can do with just a little bit of fur!

Next we checked deer traps, which are called clover traps. Mainly they wanted to catch pregnant does, so they could radio collar them and track their progress. They also used a temperature measuring device to get data on whether the doe was alive or dead and whether or not she had dropped fawn (the device would fall out upon birth as it was placed in the vagina of the animal). I got the chance to use telemetry to locate a doe and see whether or not she was alive by the frequency of the feedback.

The graduates also wanted us to have the opportunity to see what process they used when they received feedback that a doe was dead. They had a unique case where a radio-collared doe was hunted down by wolves, so we traveled over to the site and saw her remains. We were shown several ways of identifying whether it was a wolf kill or not; this included taking into consideration the space between teeth marks in bite wounds, whether there was hemorrhaging beneath the skin (this only occurs when a deer is alive and bleeding, indicating that it was being hunted) and inspecting the carcass to see if there was blood foam on the nose which indicated a crushed throat where blood from the jugular is mixed with breath. Wolves have a unique way of hunting, as does any predator, and knowing the different marks they leave can help decipher between the different predators.

After seeing the aftermath of a wolf kill, we asked if we could go out at night and try to get one to respond to howls. So with the temperatures just above -30 degrees, we ventured out into the woods and eventually to a frozen lake. We did get a few coyotes to respond, but the wolves were silent, making me wonder if they knew the difference between a recording and a real wolf or if they could smell us nearby. Either way, it was still awesome.

On the final day in Michigan, we had the best opportunity of all: getting up close and helping take measurements on wild black bears. The mother and two cubs were sedated and pulled from their den while we had the chance to touch them and help collect data. It was an incredible experience seeing the cub up close; she was licking her nose (a typical habit of sedated bears) and shivering. We did our best to keep her warm, and the work up took about an hour to complete.

It is projects like these that really give you a glimpse into a day in the field as a wildlife biologist and what can be achieved by completing this research. The data provided by this project will be used for years to come in determining whether predator control is necessary and what the real factors causing deer decline are. It gives people a glimpse into the multiple mechanisms at play when it comes to nature. There is never a simple answer.

Resources

Purdue Student Chapter of The Wildlife Society, Purdue FNR

FNR Majors & Minors, Purdue FNR

Student Life, Purdue FNR

Morgan Sussman, Freshman

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The Purdue Center for Global Soundscapes has been recognized by PBS. NOVA, a PBS documentary series focused on science, interviewed Bryan Pijanowski, Professor of Human-Environment Modeling and Analysis Laboratory, and Matt Harris, Graduate Research Assistant, to learn more on the subject and to share this story on the NOVA website in video format. Soundscape ecology is the study of how the environment changes by studying the sounds within that environment.

The Purdue Center for Global Soundscapes has been recognized by PBS. NOVA, a PBS documentary series focused on science, interviewed Bryan Pijanowski, Professor of Human-Environment Modeling and Analysis Laboratory, and Matt Harris, Graduate Research Assistant, to learn more on the subject and to share this story on the NOVA website in video format. Soundscape ecology is the study of how the environment changes by studying the sounds within that environment.

Anyone can be a citizen scientist and download their “sounds of earth” to the soundscape ecology database. There is no cost, and it is easy to do. Just visit the website, Record the Earth, for instructions.

Resources

Soundscape Ecology Research Projects, Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue Boiler Bytes Highlights Discovery Park Global Soundscape Research Center Led by FNR’s Dr. Bryan Pijanowski, Got Nature?

Bryan Pijanowski, Professor of Human-Environment Modeling and Analysis Laboratory

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Remove perches from wildlife nest boxes like the bluebird box pictured here. Perches allow undesirable birds to harass native cavity nesters and take over a nest box.

Even though we have had some rough weather lately, this winter didn’t seem so bad to me. Now that the weather forecast is looking positive and the days are getting longer (this month, we gain about 75 minutes – I am embarrassed to admit that I check this frequently during the winter because it helps me get through the winter doldrums), it is a good time to think about wildlife habitat projects.

Many species of native birds and mammals will utilize nest boxes. When we put out a nest box, all we are doing is replicating what nature already provides with cavities in both live and dead trees. Woodpeckers are primary cavity users because they create their own. Other birds and mammals are secondary cavity users because they use what is already there – either those that occur in older, dying trees or those that are created by woodpeckers. Installing nest boxes in areas where cavities are likely scarce such as urban environments or young woods may be particularly beneficial.

Tips

- Use quality materials that are weather resistant. Exterior grade plywood and lumber are good choices. Cedar and other rot-resistant woods are best. Avoid using treated lumber and metal.

- Avoid painting or staining inside nest boxes. Painting the outside can prolong its life and may be attractive for some species (white for purple martins, for example).

- The roof should be sloped to allow water runoff and should hang over the sides.

- Drill at least four 3/8-inch drainage holes on the floor.

- The roof or one side should open to allow easy access for cleaning.

- Avoid perches. Natural cavities don’t have them and neither should your nest box. Perches also allow European starlings and English house sparrows, non-native invasive species, to harass native cavity nesters and take over a nest box.

- Near the top of each side, leave gaps or drill 5/8-inch holes (at least two per side).

More tips on design, such as nest box specifics by species (dimensions, hole size and placement, box placement and location), maintenance and problem species, can be found in our Nest Boxes for Wildlife publication.

Other resources available:

Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Yard, The Education Store

Birds of Benton County, Indiana, The Education Store

Brian MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University

“When it snows…

“When it snows…

and temperatures drop,

That’s when you’ll hear

The Snap, Crackle and Pop.”

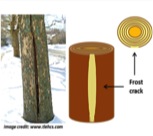

Few things can compare to the peacefulness of walking in a forest filled with snow covered trees until you hear a snap, crackle or an explosive “POP” echoing through the woods. What on earth was that? If the noise is followed by a “whoosh,” it may be a limb that just broke and crashed to the ground. If it sounded like a gunshot but nobody is there, you may be listening to the sound of a frost crack forming on a tree.

What are frost cracks?

Nobody knows for sure. You may hear one happen, typically on a cold late winter morning after a warm spell. They sound like muffled to loud rifle shots. Typically, these cracks occur on the south side of the trunk between two and five feet up the tree (when measuring from the ground). With leaves on, water is pulled upwards from tree roots through the xylem vessels by the differences in water potential from the air to the soil and escapes through the leaves (the soil-plant-air continuum).

Water in the plant is under a negative water potential, or in common terms, under tension. In the winter, when deciduous trees have no leaves, the water pressure in the sap becomes positive. A flow occurs where water moves up in the xylem and cycles down in the phloem (food conducting cells). The mechanism of this winter flow in temperate trees is not well understood physiologically. The sap increases in simple soluble sugars as the cold weather begins and increases until midwinter to work like antifreeze, depressing the freezing point of water. This is why maple syrup can be tapped in late winter.

Scientists are challenged to study the phenomena of frost cracks. They involve thousands of xylem vessels in a very narrow vertical line bursting all at once – as if a line of sap is too low in sugar concentration – and then freezes hard explosively bursting the vessels. After several growing seasons, most trees will heal over the crack, but callus growth makes them appear wider. Valuable timber logs can still be profitably harvested with frost cracks as millers can cut through them to minimize the defect.

Scientists are challenged to study the phenomena of frost cracks. They involve thousands of xylem vessels in a very narrow vertical line bursting all at once – as if a line of sap is too low in sugar concentration – and then freezes hard explosively bursting the vessels. After several growing seasons, most trees will heal over the crack, but callus growth makes them appear wider. Valuable timber logs can still be profitably harvested with frost cracks as millers can cut through them to minimize the defect.

Species with darker colored bark and thinner bark can be affected by frost cracks. Some genotype effects have been found in black walnuts at Purdue. Field conditions and topography that effect cold air movement can affect frost cracks. Most form on the southwestern section of the trunk, the area most affected by warming from sunlight during winter afternoons. Somehow, this conditioning sets up the tree when temperatures plummet to single digits (in Fahrenheit) or lower, especially after a warmer period.

So if you wander through the woods this winter, stop but don’t “drop” when you listen to the sounds of the trees.

“When the snow twinkles

and the skies are bare…

Temperatures drop

and a chill fills the air.

If you listen real close

and adjust your cap,

You just might hear

a tree go ‘Snap!’”

Resources

Bark Splitting on Trees, Cornell University

Video: How Do Trees Survive Winter? MinuteEarth

Winterize Your Trees, The Education Store

Shaneka Lawson, Adjunct Assistant Professor

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

James McKenna, Operational Tree Breeder

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University is partnering with three Indiana zoos and the state in a conservation program that will involve raising year-old hellbender salamanders and then returning them a few years later to their southern Indiana habitat to be tracked.

Purdue University is partnering with three Indiana zoos and the state in a conservation program that will involve raising year-old hellbender salamanders and then returning them a few years later to their southern Indiana habitat to be tracked.

Rod Williams, associate professor of wildlife science and leader of the university’s hellbender effort, approached officials at Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo and Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville about joining the program, which also includes the Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

North America’s largest salamander is in decline nationally and is most vulnerable to predators when young. “Mortality can be as high as 99 percent in the wild,” Williams said. “By rearing them in captivity for three to four years, they will have a much better survival rate.” Read the full article from Purdue Agriculture News.

Resources

Help the Hellbender, Purdue University

Aquaculture Research Lab, Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The Nature of Teaching, The Education Store, Purdue Extension (Search “Nature of Teaching” for a list of all available lessons)

Rod Williams, Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Department of Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR), Purdue University

Recent Posts

- Woodsy Owl Edition for Educational Learning, USDA – U.S. Forest Service

Posted: January 21, 2026 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Unexpected Plants and Animals of Indiana: Nine-Banded Armadillo

Posted: October 27, 2025 in Got Nature for Kids, Wildlife - Question: Should You Feed Birds in Summer? Understanding the Impact on Migration

Posted: May 13, 2025 in Ask the Expert, Got Nature for Kids, Wildlife - Purdue Alumnus Magazine Highlights FNR Graduate and Nature of Teaching Program

Posted: September 13, 2024 in Got Nature for Kids, Nature of Teaching, Wildlife - Magnificent Trees of Indiana Webinar

Posted: May 12, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Woodlands - “Fifty Trees of Indiana” Now Has New Name and New Additional Trees

Posted: January 13, 2022 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Introduction to Nature of Teaching Sneak Peek Videos

Posted: November 2, 2020 in Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Land Use, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Nature of Teaching Program Receives Environmental Education Award

Posted: October 30, 2020 in Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Disease, Drought, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Invasive Animal Species, Invasive Insects, Land Use, Natural Resource Planning, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Safety, Wildlife - New Publication – The Nature of Teaching: Disease Ecology

Posted: May 20, 2020 in Disease, Forestry, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Publication, Wildlife - Join us on Facebook LIVE – Hellbender Virtual Tour

Posted: April 20, 2020 in Forestry, Got Nature for Kids, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands