Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

For many people, the autumn season welcomes a pleasurable change in the weather. We notice, even during a warm fall day, the air gets cooler and the brisk breeze forces out the fleece. There are a couple of questions to be asked every year at about this time. Why do leaves change color and drop their leaves when fall weather appears? Much of it has to do with day-length and temperature. The important thing is not that the amount of sunlight has decreased but rather the amount of dark has increased. The plants we’re talking about in this case are the deciduous trees, which are the trees producing the vibrant colors and those that lose their leaves annually. These woody plants “sense” the days are getting shorter during late September as winter slowly creeps in on us. Things like pigment, light, weather conditions; plant species, soil type and location all play important roles in the fall party and colorful confetti trees create for us to enjoy.

For many people, the autumn season welcomes a pleasurable change in the weather. We notice, even during a warm fall day, the air gets cooler and the brisk breeze forces out the fleece. There are a couple of questions to be asked every year at about this time. Why do leaves change color and drop their leaves when fall weather appears? Much of it has to do with day-length and temperature. The important thing is not that the amount of sunlight has decreased but rather the amount of dark has increased. The plants we’re talking about in this case are the deciduous trees, which are the trees producing the vibrant colors and those that lose their leaves annually. These woody plants “sense” the days are getting shorter during late September as winter slowly creeps in on us. Things like pigment, light, weather conditions; plant species, soil type and location all play important roles in the fall party and colorful confetti trees create for us to enjoy.

When daylight hours are less and temperatures are cooler, photosynthesis slows down and there is less chlorophyll production. This reduction reveals yellow or orange pigment called carotenoids and are usually hidden by the abundance of chlorophyll present in leaves during the growing season.

Unlike chlorophyll and carotenoids, which are present in leaf cells throughout the growing season, anthocyanins are produced mainly in the fall. These natural chemicals give color to familiar fruits such as cranberries, red apples, cherries, and plums. These complex compounds in leaf cells react with excess stored plant sugars and exposure to sunlight creating vivid pink, red, and purple leaves. A mixture of red anthocyanin pigment and beta carotene often results in the bright orange color seen in some leaves.

The cool fall temperatures cause the closing of leaf veins and prevent sugars from moving out which prolongs fall color. Thus a succession of warm sunny days and cool crisp nights can create quite a display.

Soil moisture levels have an impact on the ability to produce good fall color. A prolonged drought can delay color change for a few weeks. The ideal conditions for producing the best colors are good summer weather, with timely rainfall, and sunny fall days with the cool night temperatures.

Tree species vary in their ability to provide fall color, as some trees just don’t produce anything noteworthy. Color depends on the nutrient levels of iron, magnesium, phosphorous, or sodium in the tree. Some tree species displaying yellow foliage are ash, birch, beech, elm, hickory, poplar, and aspen. Red leaves are seen most often in dogwood, sweet gum, sumac, and tupelo trees. Some oaks and maples present orange leaves while others range in color from red to yellow, depending on the species.

Even with these facts the timing, location, and intensity of autumn color are not completely predictable. To truly experience the colorful display you must be tuned in to your trees and your weather. Get outside and enjoy the party our woodlands are providing and enjoy nature’s beautiful confetti.

Resources:

It’s Fall, but why are the leaves still green? article and video, WLFI.com

It’s late October and many leaves on trees are still green. What’s up with that?, IndyStar.com

Why Leaves Change Color, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Why Leaves Change Color, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Trees and Storms, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

Ripe persimmon. Photo: Rebekah D. Wallace, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

The American persimmon tree’s scientific name, Diospyros virginiana, is loosely interpreted “divine fruit” or “fruit of the gods” of Virginia. If you have tasted a ripe persimmon on a crisp fall day, you might agree with that assessment. Several persimmon tree species are found in both the new and old world and have been used for food and wood products for centuries. Our American persimmon is native to the southern half of Indiana but can survive in the northern half of the state as well.

The ripe fruit is famous for the sweet orange pulp used in puddings, cookies and candies. If you are unlucky enough to eat a persimmon that has not yet ripened, your opinion of its eating quality will be quite different. Unripe persimmons have a high tannin content that makes the fruit very astringent – I describe it as feeling like your head is shrinking while simultaneously trying to expel a glue ball from your mouth! Most dedicated persimmon collectors wait for the fruit to become soft and fall from the tree before collecting to avoid this unpleasant experience. Contrary to popular belief, the fruit does not have to experience a frost to ripen. Persimmon fruit normally ripen in September and October, but some trees hold fruit well into winter.

A warning to those tempted to over-indulge in persimmon fruit: the tannin in the unripened fruit can combine with other stomach contents to form what is called a phytobezoar, a sort of gooey food ball that can become quite hard. One patient had eaten over two pounds of persimmons every day for over 40 years. Surgery is often required to remove bezoars, but a recent study indicated Coca-Cola could be used to chemically shrink or eliminate the diospyrobezoar. There is very little risk to those infrequently eating ripe persimmons.

Persimmon is related to ebony and has extremely hard wood once commonly used for golf clubs when “woods” where actually made of wood. The heartwood of persimmon can be black, like ebony, but significant dark heartwood formation may not occur until the tree is quite old. Persimmon is a medium-sized tree here in Indiana but can be over 100 feet tall in the bottomland forests of the Southern U.S. Where I grew up in Southern Indiana, my family ritual in the fall was to go to Brown County State Park and pick up persimmons, separate the tasty pulp from the skin and seeds and freeze the pulp for use in persimmon pudding and candy over the holidays. We might also collect some black walnuts or hickory nuts to include in the candy. We had to be diligent, as the opossums, raccoons and deer liked persimmon as much as we did.

The embryo in persimmon seed – is it a spoon, knife or fork? Photo: Lenny Farlee, Purdue Extension Forester

In addition to use for food, persimmon has some folk tradition related to winter weather forecasting. It was thought the shape of the embryo in the seed could predict the winter weather: a spoon shape indicated deep snow, a knife would indicate icy cutting winds and a fork meant it would be mild with plenty to eat until spring. I collected a few seeds from trees here on the West Lafayette campus and split them open to see what the tree wants to tell me – looks like a spoon to me, but you can make your own predictions.

The Indiana DNR Division of Forestry Nursery sells American persimmon seedlings. You can also find selections for fruit production being sold commercially, along with several Asian persimmon varieties. Male and female flowers are normally formed on separate trees, so plant several to get good pollination.

The following site has a wealth of information on persimmon, including several recipes and locations to buy pulp and seedlings, as well as natural and cultural history including the annual Persimmon Festival in Mitchell, Indiana:

http://www.persimmonpudding.com/.

Resources:

Persimmons, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Resources and Assistance Available for Planting Hardwood Seedlings, The Education Store

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store

Tree Planting Part 1: Choosing a Tree, video, The Education Store

Lenny D Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Food waste is a major issue in developed countries. This unit is designed to teach students about food waste and ways they can help reduce it. This section contains one unit with three lesson plans that will teach students how to reduce food waste by learning more about proper food storage, best-by dates, and ugly foods. It also contains a stand-alone lesson on food packaging and composting.

Food waste is a major issue in developed countries. This unit is designed to teach students about food waste and ways they can help reduce it. This section contains one unit with three lesson plans that will teach students how to reduce food waste by learning more about proper food storage, best-by dates, and ugly foods. It also contains a stand-alone lesson on food packaging and composting.

To view this free complete unit see: What a Waste of Food! Lesson Plans and PowerPoint, The Education Store, Purdue Extension.

Resources:

Food Preservation Methods, Purdue Extension

Washing Fresh Vegetables to Enhance Food Safety, Purdue Extension

Food Waste Lesson Plans, Nature of Teaching

Rebecca L Busse, Graduate Research Assistant

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Rod N Williams, Engagement Faculty Fellow & Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

If you care about wild animals, let them be wild. Most young wild animals you encounter are not orphaned. What may seem like an abandoned animal is normal behavior for most wildlife, to avoid predators. Picking up a wild animal you think is orphaned or abandoned is unnecessary and can be harmful to the animal or you.

If you find a wild animal that is truly abandoned, sick or injured, here is what you can do:

If you find a wild animal that is truly abandoned, sick or injured, here is what you can do:

- Leave it alone, in its natural environment. Don’t turn wildlife into pets.

- Call a licensed wild animal rehabilitator who is trained in caring for wild animals.

- If the animal is sick or severely injured, call a licensed veterinarian.

Resources:

Mammals of Indiana, J.O. Whitker and R.E. Mumford

Common Indiana Mammals, The Nature of Teaching, The Education Store-Purdue Extension’s resource center

Orphaned and Injured Animals, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

MyDNR Indiana’s Outdoor News, Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Question: This little guy lives around our house. We see him almost daily. Do you know what he is? Salamander? Skink? Lizard?

The animal pictured is both a lizard and a skink – specifically, a Common Five-lined Skink. More than 1,200 species of skinks are distributed worldwide. Most are medium-sized lizards with body lengths typically ranging 4-12 centimeters. Skinks are active and alert lizards covered with smooth overlapping scales on the sides and back.

Common Five-lined Skinks are usually 5-7 centimeters in body length(12-21 cm total length) and have smooth overlapping scales. Their heads are distinct from their necks and ear openings are smaller than the eyes. Physical characteristics of Common Five-lined Skinks vary by sex and age. Juveniles have bright blue tails and shiny black bodies marked with five yellow longitudinal stripes. Adult males are uniformly brown and develop wider heads, with red to orange coloration on the snout and jaws. Very faint stripes also might be visible on some adult males. Adult females have brownish bodies marked with five yellowish to cream longitudinal stripes and sometimes have a hint of bluish tail.

Throughout most of Indiana, Common Five-lined Skinks are a common species of open woodlands and edges where stumps, logs, woody debris, and rock piles are present. Porches and rock cover around homes and driveways offer good habitat for these lizards. Areas like these offer hiding places, areas to bask in the sun, and food. Most activity occurs on or near the ground, although they occasionally will climb trees. Their active season extends from April to October. Five-lined Skinks actively pursue a variety of invertebrates including insects, spiders and millipedes.

Resources:

Snakes and Lizards of Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

How can I tell if a snake is venomous, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Brian MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry & Natural Resources, Purdue University

Teachers, parents and outdoor enthusiasts will want to download this free new Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources publication, The Great Clearcut Controversy. In this inquiry-based teaching unit, students use real scientific data to investigate how a bird community and individual forest animals respond to a clearcut timber harvest. In this investigation, students: use scientific inquiry to gain knowledge and answer questions; apply that knowledge to the engineering design process; and design a viable management solution given the constraints and tradeoffs they discover. All materials used in the three lessons are easily accessible and free.

Teachers, parents and outdoor enthusiasts will want to download this free new Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources publication, The Great Clearcut Controversy. In this inquiry-based teaching unit, students use real scientific data to investigate how a bird community and individual forest animals respond to a clearcut timber harvest. In this investigation, students: use scientific inquiry to gain knowledge and answer questions; apply that knowledge to the engineering design process; and design a viable management solution given the constraints and tradeoffs they discover. All materials used in the three lessons are easily accessible and free.

Resources:

The Nature of Teaching, Purdue Extension

Got Nature? Podcast, Forestry and Natural Resources

Benefits of Connecting with Nature, The Education Store

Skye M Greenler, Graduate Research Assistant

Purdue University. Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Mike Saunders, Associate Professor of Ecology and Natural Resources

Purdue University, Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Have you walked outside recently and heard a loud rattling bugle coming from the sky, and thought to yourself “what in the world is making that noise?” More than likely, you were hearing the calls of sandhill cranes. Often times you can hear the calls of sandhill cranes long before you see them, and sometimes you may never even see them. Sandhill cranes can fly at altitudes exceeding 1-mile high and their calls can be heard from more than 2 miles away.

Have you walked outside recently and heard a loud rattling bugle coming from the sky, and thought to yourself “what in the world is making that noise?” More than likely, you were hearing the calls of sandhill cranes. Often times you can hear the calls of sandhill cranes long before you see them, and sometimes you may never even see them. Sandhill cranes can fly at altitudes exceeding 1-mile high and their calls can be heard from more than 2 miles away.

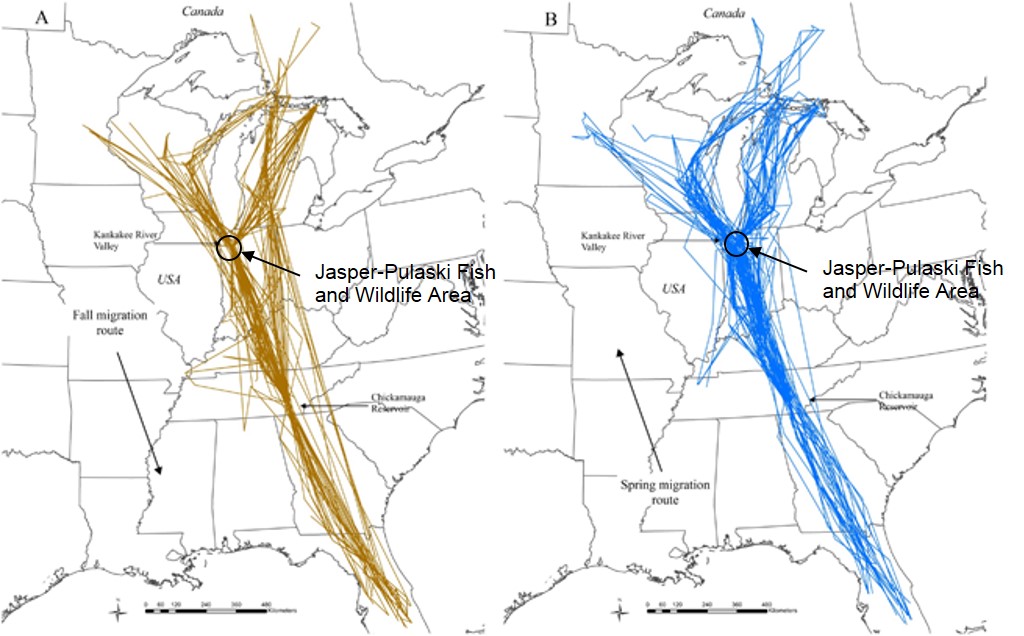

Sandhill crane sightings are a common occurrence in Indiana from October through early-December and from February through March as the cranes migrate between their breeding grounds in Michigan, Minnesota, Ontario, and Wisconsin and their wintering grounds in Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee.

When and where to view sandhill cranes in Indiana

Sandhill Cranes stopped at Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area during fall migration. Photo: Indiana DNR

While sandhill cranes can be viewed throughout the state, Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area in Medaryville, IN is one of the top spots in the eastern U.S. to view sandhill cranes. Jasper-Pulaski lies in the heart of the sandhill’s migratory path, and the birds congregate here in the thousands to tens-of-thousand during the fall and spring migration. Jasper-Pulaski serves as an important staging area for eastern sandhill cranes during migration, and the cranes stop here to rest and replenish their fat reserves to complete the migration.

Fall is the best time of year to view sandhill cranes at Jasper-Pulaski, and more specifically crane numbers are the greatest from mid-November to early-December. The Indiana DNR has a website that provides information about the sandhill crane migration at Jasper-Pulaski. Managers at Jasper-Pulaski even track the number of cranes using the area weekly, throughout the fall migration, and post an estimated count to the website. On Nov. 7th, 4,630 sandhill cranes were counted at Jasper-Pulaski. You can view cranes from the observation deck located just to the west of the Jasper-Pulaski main office.

Other hot spots to view sandhill cranes during migration include Pigeon River Fish and Wildlife Area in northeast Indiana, Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area in southwest Indiana, and Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in southeast Indiana.

Purdue Wildlife Society members assisted U.S. Fish and Wildlife Researchers with sandhill crane capture and banding at Jasper-Pulaski in the fall of 2010. Photo: Purdue Chapter of The Wildlife Society.

GPS collars on sandhill cranes highlight importance of Jasper-Pulaski

Just how important is Jasper-Pulaski to sandhill cranes? Researchers with The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the University of Minnesota attached Global Positioning System (GPS) collars to sandhill cranes to track their fall and spring migratory routes. A majority of the sandhill cranes, regardless of where spent the summer or winter, stopped at Jasper-Pulaski during the migration. Sandhill cranes spent 34% of the fall and spring migratory period at Jasper-Pulaski, which is almost twice as much time as any other single place on their migratory route. The map below shows the migratory paths taken by GPS-collared sandhill cranes during the fall (gold lines) and spring (blue lines).

The gold lines are migratory paths of individual GPS-collared sandhill cranes during the fall migration, whereas the blue lines are migratory paths during spring migration. Photo: Fronczak et al. 2017

Resources:

Sandhill Cranes Fall Migration, Indiana DNR

International Crane Foundation

Jarred Brooke, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Wild animals have a dispersal period where young move on to new ground to establish their own home range. This is nature’s way of mixing the gene pool. It also allows for species to reoccupy small, isolated habitat patches. Late summer and early fall is a common time to see juvenile snakes because of dispersal.

Snake identification questions are one of my most common that I receive from the public. Usually, people want to know if the snake is venomous or not. Most snakes in Indiana are not venomous. In fact, there are only four venomous species in Indiana. Their distributions are generally limited.

The snake pictured here to the right is a Northern Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon). Photo and identification request was submitted to our “Ask an Expert” web submission by Mr. R. Dearing. While only about a foot long here, adults can reach several feet in length. Coloration in them is variable, but they typically have dark bands on a lighter tan or brown background. The bands are complete towards the head and fragment towards the tail. This little snake found its way into Mr. Dearing’s house. Fortunately, he was able to catch it and return it to the creek behind their house—which explains why it was there in the first place.

Resources:

Snakes and Lizards of Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

How can I tell if a snake is venomous, FAQs, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Indiana Amphibian and Reptile ID Package, The Education Store, Purdue Extension

Ask An Expert, Purdue Extension-Forestry and Natural Resources

Brian MacGowan, Extension Wildlife Specialist

Department of Forestry & Natural Resources, Purdue University

Purdue University has teamed up with four zoos to protect hellbenders. This effort is a worldwide collaboration as zoos, government agencies, and other conservation groups, implement much-needed conservation initiatives. This recently published publication titled How Our Zoos Help Hellbenders shares the current zoos in Indiana that are collaborating with Purdue in this conservation effort. Zoos are conservation and research organizations that play critical roles both in protecting wildlife and their habitats and in educating the public. Thus, with hellbenders experiencing declines over the past several decades, teaming up with zoos in order to preserve and protect the hellbender species is ideal. The zoos that are currently partners with Purdue University in this effort are: Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville, Indiana; Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette, Indiana; Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo in Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Nashville Zoo in Nashville, Tennessee.

Purdue University has teamed up with four zoos to protect hellbenders. This effort is a worldwide collaboration as zoos, government agencies, and other conservation groups, implement much-needed conservation initiatives. This recently published publication titled How Our Zoos Help Hellbenders shares the current zoos in Indiana that are collaborating with Purdue in this conservation effort. Zoos are conservation and research organizations that play critical roles both in protecting wildlife and their habitats and in educating the public. Thus, with hellbenders experiencing declines over the past several decades, teaming up with zoos in order to preserve and protect the hellbender species is ideal. The zoos that are currently partners with Purdue University in this effort are: Mesker Park Zoo in Evansville, Indiana; Columbian Park Zoo in Lafayette, Indiana; Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo in Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Nashville Zoo in Nashville, Tennessee.

Three videos have been released showing how the zoos are working with Purdue University to help protect hellbenders. You can check them out below!

Resources:

Conservation Efforts, Mesker Park Zoo

Hellbender Research Participation Spotlight, Columbian Park Zoo

Conservation, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo

Hellbender Conservation, Nashville Zoo

Purdue Partners with Indiana Zoos for Hellbender Conservation – Purdue Newsroom

Help the Hellbender, Purdue Extension-FNR

Nature of Teaching, Purdue Extension-FNR

I found this in my barn. Is it a Hellbender? – Purdue FNR Extension, Got Nature

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Students in Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) continue to volunteer for Hands of the Future, Inc., a non-profit program whose mission is to help educate children about the outdoors and natural resources. As this program continues to grow, one of their dreams has been to find woods to create a children’s forest. To have a natural site that has been embellished upon with children’s needs in mind and to encourage outdoor play and adventures.

The students plan on transforming 18.8 acres of idle woods into Zonda’s Children’s Forest. The children’s forest will be composed of six main areas:

- A children’s garden, equipped with a greenhouse and kitchen, th

at’ll allow children to learn how to properly grow and cook food.

at’ll allow children to learn how to properly grow and cook food. - An enclosed area dedicated to allowing children having fun and safe adventures.

- A viewing area for butterflies, birds and other organisms of the wild, allowing children to easily enjoy the life of the forest.

- A maze designed by sunflowers, where children can have fun and do problem-solving, while close to nature.

- A walk dedicated to viewing the owls and other organisms composing the forest.

- Another enclosed area of the woods for adventures; However, it’ll also contain tree houses, bridges and other fun additions for the children.

Donations:

Donations to help make Zonda’s Children’s Forest a reality can be made here. They have six months to raise $235,000 in order to purchase the woods.

Volunteers & Interns:

Older students and adults can apply to be a volunteer. Volunteers are always appreciated, no past experience necessary. If you love nature and kids you will enjoy this program. Internships are available for college students, contact Zonda Bryant.

Resources:

Hands of the Future, Inc.

Junior Nature Club

Zonda Bryant, Director

765.366.9126

director@hands-future.org

Recent Posts

- Magnificent Trees of Indiana Webinar

Posted: May 12, 2023 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Webinar, Woodlands - “Fifty Trees of Indiana” Now Has New Name and New Additional Trees

Posted: January 13, 2022 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Multidisciplinary Cicada Outreach Team Honored by PUCESA

Posted: January 7, 2022 in Ask the Expert, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Introduction to Nature of Teaching Sneak Peek Videos

Posted: November 2, 2020 in Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Land Use, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Nature of Teaching Program Receives Environmental Education Award

Posted: October 30, 2020 in Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Disease, Drought, Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Gardening, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Invasive Animal Species, Invasive Insects, Land Use, Natural Resource Planning, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Safety, Wildlife - New Publication – The Nature of Teaching: Disease Ecology

Posted: May 20, 2020 in Disease, Forestry, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Nature of Teaching, Plants, Ponds, Publication, Wildlife - Join us on Facebook LIVE – Hellbender Virtual Tour

Posted: April 20, 2020 in Forestry, Got Nature for Kids, Wildlife, Woodlands - The Nature of Teaching: Adaptations for Aquatic Amphibians

Posted: May 14, 2019 in Alert, Aquaculture/Fish, Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources, Got Nature for Kids, How To, Nature of Teaching, Ponds, Publication, Safety, Wildlife - Can Groundhogs Predict the Weather?

Posted: January 31, 2019 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Publication and Lesson Plans for Food Waste and Natural Resources

Posted: December 12, 2018 in Got Nature for Kids, Natural Resource Planning, Nature of Teaching, Publication

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands