Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Wild Bulletin, IN DNR Fish and Wildlife: In September, DNR biologists found two species of salamander, the long-tailed salamander, and the southern two-lined salamander, in Knox County, marking the first time since the 1800s that either has been documented along the lower Wabash River.

While both species are more widespread in other parts of southern Indiana, the small, rocky streams they inhabit are less common along the lower Wabash. Following this discovery, additional surveys conducted in parts of Knox, Posey, and Sullivan counties revealed more populations of southern two-lined salamanders; however, Knox County contains the only known location of a long-tailed salamander population in the region.

Salamanders and other amphibian surveys conducted by DNR biologists are supported by the Nongame Wildlife Fund. Contributions to this fund support a variety of rare and endangered wildlife.

Please visit Nongame and Endangered Wildlife to determine animals that are listed by the Indiana DNR as endangered or special concerns.

Resources:

Help the Hellbender, Purdue College of Agriculture

Question: Which salamander is this?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Is it a Hellbender or a Mudpuppy?, Got Nature? Blog

Amphibians: Frogs, Toads, and Salamanders, Purdue Nature of Teaching

A Moment in the Wild, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Help the Hellbender, Playlist & Website

The Nature of Teaching: Adaptations for Aquatic Amphibians, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Hellbenders Rock!, The Education Store

Help the Hellbender, North America’s Giant Salamander, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Wild Bulletin, IN DNR Fish and Wildlife: Indiana hunters multiplied by all their harvest equals a lot of data. Keep track of DNR’s current harvest data and comparisons to previous seasons with our handy dashboard, which is updated daily throughout deer season. While the green bars indicate the season-to-date comparison to previous seasons, the blue bars illustrate the previous season counts after the current date. The numbers at the top show the harvest season totals.

DNR’s online game check-in system was first offered in 2012 and made the primary system in 2015. The preliminary data reported on this page from this system are updated once per day during deer hunting seasons. To view the data collected, please view the Indiana Deer Harvest data.

Resources:

Indiana Hunting & Trapping Guide, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IN DNR), Fish & Wildlife

Indiana 2022-2023 Hunting & Trapping Season (pdf) list, IN DNR, Fish & Wildlife

Indiana DNR Shares 2022-2023 Hunting Season, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources

Wildlife Habitat Hint: Trail Camera Tips and Tricks, Got Nature? Blog

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 1, Field Dressing, Video, Purdue Extension Youtube channel

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 2, Hanging & Skinning, Video

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 3, Deboning, Video

Handling Harvested Game: Episode 4, Cutting, Grinding & Packaging, Video

How to Score Your White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

White-Tailed Deer Post Harvest Collection, video, The Education Store

Age Determination in White-tailed Deer, video, The Education Store

Managing Your Woods for White-Tailed Deer, The Education Store

Bovine Tuberculosis in Wild White-tailed Deer, The Education Store

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the sixth of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Northern Red Oak or Quercus rubra.

This native species is easily identified by its bark and its acorn. The bark looks like ski tracks or long running ridges that run up and down the sides of the tree, while the fruit is a large rounded acorn featuring a tight shallow cap with tight scales that resembles a beret sitting on top of a head.

Like other members of the red oak group, the leaves are multi-lobed and have bristle tips, including a sharp bristle tip on the terminal lobe. On the northern red oak, the alternately held leaves have veins that are palmate, or run out to the ends of the lobes from a single point in the middle. In the fall, the dark green leaves change to a bright red color.

The cluster of terminal buds at the end of northern red oak stems are smooth, shiny and reddish brown to brown in color. The twigs are somewhat angular in appearance.

Northern red oaks, which grow to 60 to 75 feet tall, are found mostly in upland areas. The natural range of northern red oak is the eastern United States and southern Canada, with the exception of the southern coastal plains. It grows well on moist, but well-drained soils.

The Morton Arboretum states that northern red oak has a high tolerance of salt and air pollution, making it a good tree for more exposed areas. This species prefers a well-drained, rich woodland site and it grows best in sandy, loam soil.

As with other oaks, the northern red oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. Galls and mites are common insect problems. This species can develop chlorosis symptoms in high pH soils.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Northern Red Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning, or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Northern Red Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Northern Red Oak

Red Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

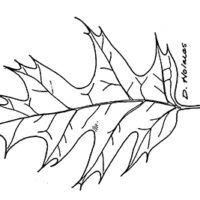

This week, we take a look at the seventh of our featured oak varieties in Indiana, the Black Oak or Quercus velutina.

The leaves of black oak are multi-lobed, typically with seven lobes, with deep sinuses in between, and have bristle tips like all members of the red/black oak family. On the black oak, the alternately held leaves can be extremely variable in shape, but the tops of the leaves are dark and shiny and have a leathery appearance. Leaves change from dark green in summer to yellow or yellow-brown in fall.

One key characteristic of black oak are the terminal buds, which are angular and fuzzy, very large and light tan. Alternately, the cluster of terminal buds at the end of northern red oak stems are smooth, shiny and reddish brown to brown in color.

The bark is very dark in color with narrow, blocky ridges, and lacks the silvery running ridges that are found on northern red oak.

The fruit is a small rounded acorn with striping running up and down the sides and a fuzzy coating along the outside edge. The cap is deeper than northern red oak and the scales on the edge of the cap resemble loose, rough shingles.

Black oaks, which grow to 50 to 60 feet tall, are found mostly in dry, upland areas. The natural range of the black oak is nearly all of the eastern United States, from Nebraska, Iowa and Oklahoma to the west, dipping south into Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and even a bit of the panhandle of Florida, extending along the eastern coastline, and northward into southern Ontario, Canada.

The Morton Arboretum states that black oak has a high tolerance of alkaline soils and dry sites, although it prefers acidic and dry soil. This species cannot withstand severe drought. It can also be difficult to transplant due to a deep taproot.

As with other oaks, the black oak should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt, which can be a potential disease problem. Galls on leaves caused by mites or insects are common, but not harmful.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Black Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Black Oak

ID That Tree: Red Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: Red Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Black Oak

Black Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

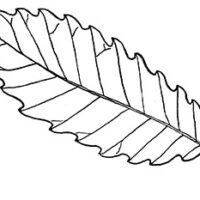

This week, we take a look at the fifth of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Chinkapin Oak or Quercus muehlenbergii.

Also known as the Chinquapin Oak, the leaves of this species feature shallow, evenly lobed margins, but appear to have sharp-pointed teeth at the end resembling red or black oaks. This sharp point, however, is due to a gland at the end of the leaves, and there is no bristle tip as are typically found on red and black oaks. The shape of the leaves can be either broad like chestnut oak, or narrower.

Like other members of the white oak group, the bark of chinkapin oak is light gray and ashy, however it has a flaky appearance.

The fruit of the chinkapin oak is a small acorn that is dark brown or almost black in color. It has a cap that resembles a stocking cap, covering a third or half of the acorn, that features loose knobby scales. Under the cap, the acorn has a large white spot similar to that of a buckeye.

Chinkapin oaks, which grow to 50 to 80 feet tall, are found in both upland and bottomland areas. The natural range of chinkapin oak is the eastern United States, with the exception of the Atlantic coast and the immediate gulf coastal plains.

The Morton Arboretum states that chinkapin oak is best grown in rich, deep soils, but that it is often found in the wild on dry, limestone outcrops in low slopes and wooded hillsides. It notes that this species is one of the best oaks for alkaline soils. As with other oaks, this chinkapin oaks should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. This species also can be affected by anthracnose, oak wilt and two-lined chestnut borers.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Chinkapin Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning, or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Chinkapin Oak

ID That Tree: White Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: White Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Chinkapin Oak

Chinkapin Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Fort Wayne Purdue

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment, Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

With winter upon us this is actually a good time to look for owls on your property. Most owls breed from January to March. You can either listen for calls in the evening, or use owl calls or recorded calls to get responses from owls in the area. We have three common species in Indiana and one rare species. All are non-migratory. However, each has different needs and habits. The following descriptions were written by Barny Dunning, professor of wildlife ecology at Purdue. These accounts were originally published in the Indiana Woodland Steward (www.inwoodlands.org).

Owls are among the most intriguing animals native to Indiana. They have been celebrated in story from the myths of the early Greeks to the books of Harry Potter. Owls are common across much of the state, but are relatively unknown, probably because of the nocturnal habits of these birds. But since they are efficient predators of mice and rats, among other things, owls are very useful birds to have around. Three species of owls are common year-round residents in Hoosier forests. The largest of these is the great horned owl, one of the dominant predators of our forests. Most people are surprised to learn that the great horned owl is as common as the familiar redtailed hawk even though the owl is much less likely to be seen.

Great horned owls hunt in open areas but nest in large trees, where they take over a nest abandoned by a hawk, crow or heron. They are common where both woods and fields mix. The owls start breeding in January and February, adding new sticks to an old nest and laying a clutch of three eggs. Most species of owls nest very early in the year so that there will be a lot of easily caught prey in the form of young mammals and birds when the owl chicks are learning to hunt on their own. Many nests of the great horned owl are in snags or trees with broken tops, therefore retaining some of these forest features will provide good nesting spots for this dominant bird.

A second species of large owl is found in the larger woodlands of Indiana. The barred owl is most common in the interiors of forests and spends less time along the woodland edge. One major reason for this is the presence of the great horned owls, which will kill and eat a barred owl. Barred owls usually nest in the cavities of deciduous trees, laying their eggs in deep winter. Their dependence on tree cavities means that barred owls are likely to respond well to land management activities that retain large trees on a property and increase the number of snags with cavities. They also do well when there are forest patches of a variety of ages on a property, in addition to the older trees that provide nest sites.

Eastern screech-owls are the smallest resident owl in the state. They nest in small tree cavities and readily make use of nest boxes made especially for them. More than the other two species, screech-owls are found in suburban backyards, urban parks and on college campuses – anywhere there is a variety of trees and shrubs. Screech-owls feed on small prey such as insects, songbirds and mice. They breed later than do the big owls and have active nests in March and April. In addition to nest boxes, these owls will use old cavities excavated by northern flickers, tree holes created by storm damage, and hollow trunks of snags. Their ready use of a wide variety of cavity types makes our screech-owls a prime beneficiary of snag retention and other habitat improvement activities. Indiana’s smallest owl does not breed here, but its numbers during the fall migration can be in the thousands statewide. The northern saw-whet owl breeds from the most northern states on into Canada and migrates from there when food becomes scarce. “Swets” are an irruptive species, meaning their populations rise and fall dramatically from one year to the next on a roughly four-year cycle. A group of volunteer researchers in Yellowwood State Forest began studying the movements of these owls in 2002 as part of the larger Project Owlnet (www.projectowlnet.org). Their first year produced 71 owls on just one ridge in Yellowwood. Since then, the annual numbers have averaged around 70, but nearly 200 owls were captured and banded on that same ridge in 2007. The low point in the cycle was in 2009 when only nine owls were captured. There are now eight such banding stations scattered around Indiana. Brookeville Reservoir had the largest number of captures in 2009 with 32; while an Indianapolis station tallied only six. Some northern saw-whet owls winter in Indiana where forests with an open understory provide good foraging opportunities throughout the winter months.

The rarest owl in Indiana is, paradoxically, the species with the largest geographic range. Barn owls are found across the globe, but in the Midwestern United States their populations have declined dramatically. The species is considered endangered in Indiana. Barn owls originally nested in tree cavities, but when early settlers built barns and other farm buildings, the owls were quick to adapt. They are not limited to barns however, as recent Hoosier nests have been found in old churches, silos, and within the walls of abandoned buildings. To be suitable, human structures must have openings that allow the owls to fly in and out and an interior area that is undisturbed and big enough for the nest. The biggest factor in their decline has been changing agricultural practices. Barn owls hunt in open areas such as pastures, but do not use row crop fields. As Hoosier farmers converted pastures to corn and soybean, the barn owl lost its hunting grounds. Farmers in the southern part of the state that still retain some open grassy fields on their land can contact the state Department of Natural Resources to have a barn owl nest box added to their outbuildings if they don’t have appropriate nest sites.

Resources

Learn how forests are used by birds new videos, Got Nature? Blog

Managing Woodlands for Birds, The Education Store-Purdue Extension resource center

National Audubon Society

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Brian MacGowan, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue University, Forestry and Natural Resources

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced it is awarding $197 million for 41 locally led conservation projects through the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). RCPP is a partner-driven program that leverages partner resources to advance innovative projects that address climate change, enhance water quality, and address other critical challenges on agricultural land.

“Our partners are experts in their fields and understand the challenges in their own backyards,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said. “Through RCPP we can tap into that knowledge, in partnership with producers and USDA, to come up with lasting solutions to the challenges that farmers, ranchers, and landowners face. We’re looking forward to seeing the results of public-private partnership at its best, made possible through these RCPP investments.”

The “Farmers Helping Hellbenders” project, led by Dr. Rod Williams and Purdue Extension wildlife specialist/Help the Hellbender project coordinator Nick Burgmeier, is among the projects set to receive funding through the RCCP Classic fund, which uses NRCS contracts and easements with producers, landowners and communities in collaboration with project partners.

Fourteen contributing partners will assist in the project:

- Mesker Park Zoo and Botanic Gardens

- Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo

- Indianapolis Zoo

- Indiana Department of Environmental Management

- Crawford County Soil and Water Conservation District

- Floyd County Soil and Water Conservation District

- Harrison County Soil and Water Conservation District

- Washington County Soil and Water Conservation District

- Crawford County Cattleman’s Association

- Harrison County Cattleman’s Association

- Washington County Cattleman’s Association

- Cryptobranchid Interest Group

- The Nature Conservancy

- Wallace Center at Winrock International

With help from nearly $2.7 million in RCCP funding, the project aims to improve hellbender habitat in a four-county region in south central Indiana, the only remaining habitat for hellbenders in the state, by expanding the use of agricultural conservation practices that lead to decreased sedimentation in local rivers systems.

Sedimentation is a major cause of hellbender decline and reduced sedimentation will increase available habitat for hellbenders, mussels, and aquatic macroinvertebrates. This project also will address soil and nutrient loss, which are concerns for agricultural producers, as the targeted conservation practices and systems have been shown to have long-term benefits for agricultural systems and operations.

“Through this initiative, focused on Crawford, Floyd, Harrison, and Washington counties, we expect to improve water quality and aquatic wildlife habitat,” Burgmeier said. “Simultaneously, we hope to improve soil retention and nutrient availability to crops by helping farmers implement practices such as cover crops, riparian buffers, grassed waterways, etc. Additional benefits will include increases in riparian and pollinator habitat and increased protection for karst habitat through the selected targeting of sinkholes.”

“Through this initiative, focused on Crawford, Floyd, Harrison, and Washington counties, we expect to improve water quality and aquatic wildlife habitat,” Burgmeier said. “Simultaneously, we hope to improve soil retention and nutrient availability to crops by helping farmers implement practices such as cover crops, riparian buffers, grassed waterways, etc. Additional benefits will include increases in riparian and pollinator habitat and increased protection for karst habitat through the selected targeting of sinkholes.”

As part of each project, partners offer value-added contributions to amplify the impact of RCPP funding in an amount equal to or greater than the NRCS investment. Private landowners can apply to participate in an RCPP project in their region through awarded partners or at their local USDA service center.

“RCPP puts local partners in the driver’s seat to accomplish environmental goals that are most meaningful to their community. Joining together public and private resources also harnesses innovation that neither sector could implement alone,” Indiana NRCS State Conservationist Jerry Raynor said. “We have seen record enrollment of privately owned lands in NRCS’ conservation programs and RCPP will be instrumental in building on those numbers and demonstrating that government and private entities can work together for greater impacts on Indiana’s communities.”

For much of the last 16 years, Williams and his team have been researching eastern hellbenders, spearheading regional conservation efforts and advancing hellbender captive propagation, or the rearing of this ancient animal in captivity and their eventual return to the wild.

Additional Resources

Improving Water Quality by Protecting Sinkholes on Your Property video

Improving Water Quality Around Your Farm video

Adaptations for Aquatic Amphibians

Hellbenders Rock! Nature of Teaching Lesson Plan

Nature of Teaching – Hellbenders Rock Sneak Peek video

Nature of Teaching – Hellbenders Rock webinar video

Learn about hellbenders and take a tour of Purdue’s hellbender rearing facility video

Learn about the hellbender work at Mesker Park Zoo video

Learn about hellbender work at The Wilds video

Dr. Rod Williams’ 2017 TEDx Talk Help the Hellbenders video

A Moment in the Wild – Hellbender Hides video

A Moment in the Wild – Hellbender Release video

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Rod Williams, Assistant Provost for Engagement/Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

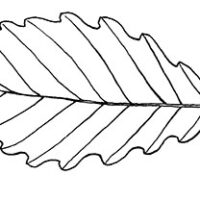

This week, we take a look at the third of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Swamp White Oak or Quercus bicolor.

The swamp white oak has leaves with wavy, uneven lobed margins with blunt teeth, which are wider toward the tip than at the base. The alternately-held leaves are typically dark green on top with a silvery-white underside, which turn orange, gold and yellow in the fall.

The bark on swamp white oak is similar to that of white oak and often peels back especially on younger trees. Mature bark is dark gray-brown with flaky/shreddy bark or blocky ridges that are consistent up and down the tree.

The fruit of the swamp white oak is an acorn held on a long stalk, typically an inch or inch and a half long, called a peduncle.

Swamp white oaks, which grow to 50 to 60 feet tall, are named for the fact that they often grow in wet places, such as line drawing of swamp white oak acorns and peduncle. upland swamps and lowlands. This species also can tolerate well-drained upland sites, making it a good option for landscape plantings. The natural range of swamp white oak is the northern half of the eastern United States, reaching as far south as Missouri, southern Illinois and Kentucky, and north into Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The Morton Arboretum warns to plant swamp white oak in full sun and shares that the species is one of the easiest oaks to transplant and is more tolerant of poor drainage than other oaks. It also notes that oaks should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. Swamp white oak can be affected by pests such as anthracnose, powdery mildew, chlorosis in high pH soils, insect galls and oak wilt.

In general, lumber from the white oak group is among the heaviest next to hickory, weighing in at 47 pounds per cubic foot. It is very resistant to decay and is one of the best woods for steam bending.

White oak lumber has been used for a variety of purposes including log cabins, ships, wagon wheels and furniture. It also is preferred for indoor decorative applications ranging from furniture, especially in churches, to cabinets, interior trim, millwork and hardwood flooring and veneers. It also may be used for barrel making.

Its density and durability make white oak a favorite for industrial applications such as railroad ties, mine timbers, sill plates, fence posts and boards, pallets, and blocking, as well as industrial, agricultural and truck flooring.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Swamp White Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Swamp White Oak

ID That Tree: White Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: White Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Swamp White Oak

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The classic and trusted book “Fifty Common Trees of Indiana” by T.E. Shaw was published in 1956 as a user-friendly guide to local species. Nearly 70 years later, the publication has been updated through a joint effort by the Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Indiana 4-H, and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and reintroduced as “An Introduction to Trees of Indiana.”

The full publication is available for download for $7 in the Purdue Extension Education Store. The field guide helps identify common Indiana woodlot trees.

Each week, the Intro to Trees of Indiana web series will offer a sneak peek at one species from the book, paired with an ID That Tree video from Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee to help visualize each species as it stands in the woods. Threats to species health as well as also insight into the wood provided by the species, will be provided through additional resources as well as the Hardwoods of the Central Midwest exhibit of the Purdue Arboretum, if available.

This week, we take a look at the fourth of our oak varieties in Indiana, the Chestnut Oak or Quercus montana.

The leaves of the chestnut oak have small, evenly lobed rounded margins. The upper leaf surface is leathery in appearance and is dark green in color, while the lower surface is a duller green. In the fall, the leaves can range from red and orange to yellow and brown.

The bark may be its tell-tale characteristic. Unlike other members of the white oak group, the bark of Chestnut oak bark chestnut oak is dark and deeply ridged.

The fruit of the chestnut oak is a relatively-large dark brown acorn with a smooth edge on the outer margin of the cap.

Chestnut oaks, which grow to 60 to 70 feet tall, are often found on high, dry sites in Indiana. The natural range of chestnut oak is across the northeastern United States, extending south to the northern parts of Alabama and Georgia and west to the southern tip of Illinois.

The Morton Arboretum warns that chestnut oak is a difficult to transplant due to a deep taproot, but that it can tolerate most soils except those that drain poorly. It also notes that oaks should be pruned in the dormant season to avoid attracting beetles that may carry oak wilt. Chestnut oak can be affected by pests such as scale insects and two-lined chestnut borer. Chestnut oak acorns

In general, lumber from the white oak group is among the heaviest next to hickory, weighing in at 47 pounds per cubic foot. It is very resistant to decay and is one of the best woods for steam bending. Chestnut oak, however, is considered a poor lumber species.

White oak lumber has been used for a variety of purposes including log cabins, ships, wagon wheels and furniture. It also is preferred for indoor decorative applications ranging from furniture, especially in churches, to cabinets, interior trim, millwork and hardwood flooring and veneers. It also may be used for barrel making.

Its density and durability make white oak a favorite for industrial applications such as railroad ties, mine timbers, sill plates, fence posts and boards, pallets, and blocking, as well as industrial, agricultural and truck flooring.

For full article with additional photos view: Intro to Trees of Indiana: Chestnut Oak, Forestry and Natural Resources’ News.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Other Resources:

ID That Tree: Chestnut Oak

ID That Tree: White Oak Group

Hardwood Lumber and Veneer Series: White Oak Group

Morton Arboretum: Chestnut Oak

Fifty Common Trees of Indiana

An Introduction to Trees of Indiana

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

ID That Tree, Purdue Extension-Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube playlist

Woodland Management Moment , Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube playlist

Chestnut Oak, Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue-Fort Wayne

Wendy Mayer, FNR Communications Coordinator

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- ID That Tree: Sugarberry

Posted: December 12, 2025 in Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Powering Rural Futures: Purdue’s Agrivoltaics Initiative for Sustainable Growth

Posted: December 9, 2025 in Community Development, Wildlife - Learn How to Control Reed Canarygrass

Posted: December 8, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Benefits of a Real Christmas Tree, Hoosier Ag Today Podcast

Posted: December 5, 2025 in Christmas Trees, Forestry, Woodlands - Succession Planning Resource: Secure your Future

Posted: December 2, 2025 in Community Development, Land Use, Woodlands - A Woodland Management Moment: Butternut Disease and Breeding

Posted: December 1, 2025 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Woodland Management Moment, Woodlands - Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

Posted: in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Red in Winter – What Are Those Red Fruits I See?

Posted: in Forestry, Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Managing Common and Cut Leaved Teasel

Posted: November 24, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Extension Team Wins Family Forests Comprehensive Education Award

Posted: November 21, 2025 in Forestry, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands