Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

You’ve heard about all the traditional careers. But what about being an outdoor scientist? Introducing the world to The Familiar Faces Project which shares careers in fisheries, aquatic sciences, forestry, wildlife and sustainable biomaterials. This video will show by example what it’s like to be an outdoor scientist, walking you through a typical work day of Megan Gunn. For more information about The Familiar Faces Project, contact thefamiliarfacesproject@gmail.com.

Resources:

Aquatic Ecology Research Lab, Forestry and Natural Resources

Megan Gunn, Aquatic Ecology Research Scientist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Question from Josh L Lady: Which salamander is this?

Question from Josh L Lady: Which salamander is this?

Answer:

The picture posted is one of our mole salamanders (family Ambystomatidae). This common family name comes from their habit of staying underground and in burrows of other creatures, except when breeding. Species in this family can be difficult to tell apart at times. Adding to the confusion, there is a species called the Mole salamander (Ambystoma talpoideum) which in Indiana is only found in the extreme southwestern part of the state.

The species below is likely a Small-mouthed Salamander (Ambystoma texanum). It can be found throughout Indiana except the extreme northwestern and southeastern portions of the state. The Small-mouthed Salamander is a moderate sized salamander characterized by its slender head and small mouth. Most individuals are dark gray to grayish brown with light gray speckles (often resembling lichen-like markings), particularly on the lower sides of the body. Adults usually reach 11-19 cm in length and have an average of 15 costal grooves (i.e., the “wrinkles” on the sides of the body; range 13-15).

I say it is likely a Small-mouthed Salamander because they are nearly identical to in appearance to the Streamside Salamander (Ambystoma barbouri). There are minor differences in the teeth and premaxillary bones between the two species; however, these structures are not readily observable in the field. Geographic location and habitat type are the best ways to distinguish these two species. Streamside Salamanders are restricted to extreme southeastern Indiana, occupy hilly areas, and breed in streams. Small-mouthed Salamanders exist nearly statewide, occur in wooded floodplains, and breed in ephemeral wetlands.

Resources:

Salamanders of Indiana, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center.

Appreciating Reptiles and Amphibians, The Education Store

Forest Management for Reptiles and Amphibians: A Technical Guide for the Midwest, The Education Store

Ranavirus: Emerging Threat to Amphibians, The Education Store

Brian MacGowan, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources

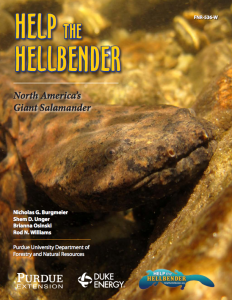

The eastern hellbender is a large, fully aquatic salamander that requires cool, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Because they require high-quality water and habitat, they are thought to be indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. While individuals may live up to 29 years, possibly longer, many populations of this unique salamander are in decline across their geographic range. It is the largest salamander in North America, found in and around rivers and streams in 17 states from New York to Missouri. Many hellbender populations are in decline within their geographic range. This publication provides information on identifying and preserving this important aquatic animal. You can find Help the Hellbender, FNR-536-W, as well as other great resources that can be found at The Purdue Education Store.

The eastern hellbender is a large, fully aquatic salamander that requires cool, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Because they require high-quality water and habitat, they are thought to be indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. While individuals may live up to 29 years, possibly longer, many populations of this unique salamander are in decline across their geographic range. It is the largest salamander in North America, found in and around rivers and streams in 17 states from New York to Missouri. Many hellbender populations are in decline within their geographic range. This publication provides information on identifying and preserving this important aquatic animal. You can find Help the Hellbender, FNR-536-W, as well as other great resources that can be found at The Purdue Education Store.

Resources:

How Anglers and Paddlers Can Help the Hellbender, The Education Store

Hellbender ID, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality by Protecting Sinkholes on Your Property, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality at Your Livestock Operation, The Education Store

Healthy Water, Happy Home – Lesson Plan, The Education Store

Nick Burgmeier, Research Biologist and Extension Wildlife Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dr. Rod Williams, Associate Head of Extension and Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) has released its latest video – Indiana’s Working Forests.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) has released its latest video – Indiana’s Working Forests.

This video explores the origins of Indiana’s state forest system that developed after pioneer settlers cleared the original forests and left behind a nearly barren landscape.

State forests were established to demonstrate how to use science to grow and sustain healthy forest systems. Beginning with just 2,000 acres at Clark State Forest in 1903, the DNR Division of Forestry has expanded to cover more than 156,000 acres at 15 sites.

In the video, IDNR Forestry professionals discuss how management practices contribute to forest health by mimicking natural disturbances. Those practices promote regeneration of oaks and hickories that are valuable food sources for many forest wildlife species. They explain that although timber harvests have increased in recent years, the selective approach they use removes less than 1 percent of the available trees in any given year.

FNR graduate wildlife student Patrick Ruhl, Purdue adviser Dr. J. Barny Dunning, Jr., shares how the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment provides him the opportunity to study the effects of forest management and the changes that are taking place among migratory songbirds. This project is a collaborative effort with the following sponsors: Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry; Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Diversity Section; Purdue University; Indiana Chapter of the Ruffed Grouse Society; National Geographic Society; and The Wildlife Management Institute. To view more partners view the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment website: heeforestudy.org.

Resources:

A Landowner’s Guide to Sustainable Forestry: Part 1: Sustainable Forestry – What does it mean for Indiana?, The Education Store

Indiana Forest Issues and Recommendations, The Education Store

The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment: Indiana Forestry and Wildlife, The Education Store

Forest Ecosystem Management in Indiana, The Education Store

Forest Ecosystem Management in the Central Hardwood Region, The Education Store

Phil Bloom, Director

Indiana Department of Natural Resources

The Eastern hellbenders are the largest salamander in North America and have survived unchanged for nearly 2 million years. Hellbender populations are declining across their range, from Missouri to New York. This decline is likely caused by human influences such as habitat degradation and destruction. Many states are developing conservation programs to help the hellbender. To find out what you can do visit helpthehellbender.org.

Resources:

How Anglers and Paddlers Can Help the Hellbender, The Education Store

Hellbender ID, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality by Protecting Sinkholes on Your Property, The Education Store

Improving Water Quality at Your Livestock Operation, The Education Store

Healthy Water, Happy Home – Lesson Plan, The Education Store

Nick Burgmeier, Project Coordinator, Research Biologist & Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Dr. Rod Williams, Associate Head of Extension and Associate Professor of Wildlife Science

Purdue Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Every hunter knows the importance of acorns for game and non-game species alike. When acorns are plentiful it can alter the movements and patterns of game species and when acorns are absent wildlife must rely on alternative food sources to meet their nutritional needs during the fall, winter, and early spring. Knowing the importance of acorns to many wildlife species, it is beneficial to identify which trees are the most reliable and best producing in the woods.

Intro to oaks

White oak acorns are clustered at the end of the branch – this year’s growth, like on this swamp white oak on the left. Whereas, red oak acorns are farther down the branch at the end of last year’s growth, like the northern red oak acorns on the right. (Photo by Brian MacGowan)

Oak trees in Indiana fall into 1 of 2 groups, white oak (e.g., white, swamp white, and chinkapin) or red oak (e.g., northern red, black, and pin). White oaks produce acorns in 1 growing season (acorns falling in 2016 are from flowers that were pollinated in the spring of 2016) and red oaks produce acorns in 2 growing seasons (acorns falling in 2016 are from flowers that were pollinated in the spring of 2015). This means a late frost in the spring may result in poor acorn production in white oaks in the fall of the same year, but will not influence red oak acorn production the same fall. However, a late frost in back-to-back years may result in a mast failure from both groups.

White oak acorns tend to be selected by wildlife more than red oak acorns because they contain less tannins resulting in a less bitter and more digestible acorn. Check out the Native Trees of the Midwest to learn more about oaks, their value for wildlife, and help you learn to identify different species.

Oak trees can be split into production groups based on their relative acorn production capabilities. Some individual oak trees are inherently poor producers and rarely produce acorns even in a bumper crop. Whereas other individuals are excellent producers and may produce acorns even in the poorest year. Research from the University of Tennessee reported poor mast producing trees represented 50% of white oaks in a stand and produced only 15% of the white oak acorn crop in a given year, whereas excellent producing trees represented 13% of white oaks, but produced 40% of the total white oak acorn production. When you included excellent and good producing white oaks together (31% of trees), they accounted for 67% of the total white oak acorn crop in a stand. This means a minority of the white oaks in a stand may produce a majority of the acorns!

Scouting oak trees

Understanding that some individual oak trees are poor producers, some are excellent, and some fall between poor and excellent, surveying oak trees can help identify important mast producing individuals. The late summer and early fall, just prior to or at the beginning of acorn drop, are perfect times to identify the best and worst producing oaks in your stand of timber. Scouting can be as formal as conducting a mast survey, National Deer Association, or as informal as taking mental notes of oak trees with heavy crops of acorns on the ground while you are walking to and from your tree stands in the fall. Either way, scouting oaks for acorn production capability can provide more information when determining where to hunt in the fall or which trees to retain and which trees to remove during a timber harvest. If wildlife management is an objective on your property, trees that you identify as the best acorn producers in the woods can be retained during a timber harvest, while poor producing trees can be removed with little detriment to overall acorn production. It is important to remember to retain a balance of oaks from both the red and white oak group, favoring red oak, to help safeguard against complete mast failures.

Forest management is insurance for mast failure

The top photo is of a mature forest with very few canopy gaps resulting in very little cover or food for wildlife. The bottom picture is of a forest stand where undesirable trees have been girdled (tree on the right-hand side of picture) to increase light to the forest floor and where multiple prescribed fire have been conducted to increase forage production and cover.

Annual acorn production in a stand of oaks is highly variably and can be dependent on environmental conditions. For example, late frosts, poor pollination, and insect infestations all can be culprits for poor mast production across a stand of oaks. Because of these factors, white oaks tend to only produce reliably 2 out of every 5 years, meaning 3 out of 5 years (60%) there is poor mast production or a failed mast crop in white oaks. Red oaks may produce a good crop as frequently as 2 to 5 years, but only produce a bumper crop an average every 5 to 7 years.

The extreme variability in acorn production underscores the importance in considering alternative food sources for fall, winter, and early spring for wildlife. In most mature forests with few canopy gaps there could be as little as 50-100 lbs of deer selected forage per acre in the understory. However, with some management, like thinning and prescribed fire the amount of deer selected forage can be increased to almost 1000 lbs/ac! Additionally, forest management also increases the amount cover throughout the year for species like white-tailed deer, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, woodcock, and many forest songbirds. Contrary to popular belief, cover can be more of a limiting factor for many wildlife species compared to food availability. Forest management could include girdling undesirable trees to expand growing space for mast producing trees or conducting a timber harvest removing undesirable trees and poor producing oak trees while retaining good producing trees. For more information on conducting a timber harvest for wildlife on your property contact a professional wildlife biologist or professional forester in your area.

When spending time in the woods this fall, take the time to look up and down to see which oaks in your woods are the best producers.

Resources:

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension’s resource center

Masting Characteristics of White Oaks: Implications for Management, University of Tennessee

Wildlife Biologists, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Find a Forester, Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)

Enrichment Planting of Oaks, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment: Indiana Forestry and Wildlife, The Education Store

Jarred Brooke, Wildlife Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Genetically Modified Organisms, or GMOs, is a topic that continues to be in the news and yet many of us know relatively little about this topic. We want to know what we’re eating, and we want to know how this topic is impacting the environment. Knowing more equips us to make the best decisions for ourselves and generations to come. That’s why The Science of GMOs website was created, to help break down the information and address some of the most important questions and concerns that many have. You can always count on this site to address this complicated and evolving issue with neutral, scientifically sound information.

Genetically Modified Organisms, or GMOs, is a topic that continues to be in the news and yet many of us know relatively little about this topic. We want to know what we’re eating, and we want to know how this topic is impacting the environment. Knowing more equips us to make the best decisions for ourselves and generations to come. That’s why The Science of GMOs website was created, to help break down the information and address some of the most important questions and concerns that many have. You can always count on this site to address this complicated and evolving issue with neutral, scientifically sound information.

Submit a question by visiting The Science of GMOs website: https://ag.purdue.edu/GMOs.

Resources:

GMO Issues Facing Indiana Farmers in 2001, The Education Store

Grain Quality Issues Related to Genetically Modified Crops, The Education Store

Field Crops: Corn Insect Control Recommendations – 2015, The Education Store

Indiana Vegetable Planting Calendar, The Education Store

Choosing and planting a tree should be a well-informed and planned decision. Proper selection and planting can provide years of enjoyment for you and future generations as well as increased property value, improved environmental quality, and economic benefits. On the other hand, an inappropriate tree for your site or location can be a continual challenge and maintenance problem, or even a potential hazard, especially when there are utilities or other infrastructure nearby. This informative video will describe everything needed to know about choosing the right tree.

Resources:

Financial and Tax Aspect of Tree Planting, The Education Store

Tree Risk Management, The Education Store

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife, The Education Store

Importance of Hardwood Tree Planting, The Education Store

Planning the Tree Planting Operation, The Education Store

Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Recent Posts

- ID That Tree: Sugarberry

Posted: December 12, 2025 in Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Powering Rural Futures: Purdue’s Agrivoltaics Initiative for Sustainable Growth

Posted: December 9, 2025 in Community Development, Wildlife - Learn How to Control Reed Canarygrass

Posted: December 8, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Benefits of a Real Christmas Tree, Hoosier Ag Today Podcast

Posted: December 5, 2025 in Christmas Trees, Forestry, Woodlands - Succession Planning Resource: Secure your Future

Posted: December 2, 2025 in Community Development, Land Use, Woodlands - A Woodland Management Moment: Butternut Disease and Breeding

Posted: December 1, 2025 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Woodland Management Moment, Woodlands - Controlling Introduced Cool-Season Grasses

Posted: in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Red in Winter – What Are Those Red Fruits I See?

Posted: in Forestry, Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - Managing Common and Cut Leaved Teasel

Posted: November 24, 2025 in Forestry, Invasive Plant Species, Wildlife - Extension Team Wins Family Forests Comprehensive Education Award

Posted: November 21, 2025 in Forestry, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands