Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Purdue University - Extension - Forestry and Natural Resources

Got Nature? Blog

Question: Often ginkgo trees will drop all of their leaves on a single day after a cold night. I thought that was going to be Monday at Purdue (left: leaves falling). But no, we’re at Wednesday now (right) and this one changed its mind. Anyone know how common that is?

Answer: It was a very peculiar fall. The overall leaf drop was one to two weeks later than normal at least. An October with weather more like September has likely had some impact on this. Individual trees will vary some on their leaf drop timing, probably due to their geographic origin (for planted trees) and individual genetic variation. The severity and timing of frost/freeze also influences strongly. As you can see, lots of variables!

Leaf drop is not solely dependent on temperatures. There is a process of dormancy the tree follows to properly acclimate in preparation for winter. One of these is leaf drop, but it must go through the process of developing an abscission layer between the petiole base and branch. Most likely, the tree didn’t drop leaves yet because this separation layer of chemicals hasn’t fully responded yet. We often see frozen leaves on a tree and later they fall, but this is the result of sudden extreme cold ahead of proper dormancy routines.

Resources:

Fall Color Pigments, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Why Leaves Change Color – The Physiological Basis,

Oak Wilt in Indiana, Purdue Landscape Report

Dog Days of Summer Barking Early This Year, Purdue Landscape Report

Tulip Poplar Summer Leaf Drop, Purdue Landscape Report

Be on the Lookout for Defoliated Viburnums and Viburnum Leaf Beetle, Purdue Landscape Report

Will my Trees Recover After Losing Their Leaves?, Purdue Landscape Report

What Do Trees Do in the Winter?, Purdue Landscape Report

Why Fall Color is Sometimes a Dud, Purdue Landscape Report

Alternatives to Burning Bush For Fall Color, Purdue Landscape Report

Start Preparing Trees for Winter and Next Year, Purdue Landscape Report

ID That Tree Winter Edition: Opposite Leaf Arrangement – Ohio buckeye, Red Maple, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

ID That Tree Winter Edition: Alternate Leaf Arrangement – Black Walnut, Eastern Cottonwood, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

ID That Tree Winter Edition: Alternate Leaf Arrangement – Honey Locust, Burr Oak, Purdue Extension YouTube Channel

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lindsey Purcell, Urban Forestry Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Meet overcup oak, a species found on swampy ground and soils in southwestern Indiana. It is identifiable by its deeply sinused alternately arranged leaves as well as its acorns, which have a cap which encases nearly the entire acorn and typically don’t let go easily.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Overcup Oak, Native Trees of Indiana Riverwalk Purdue Fort Wayne

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

In this edition of ID That Tree, Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee introduces you to a native Indiana tree that provided a substitute for coffee in its past. Meet the Kentucky coffee tree, which is known by its large pods, doubly-compound leaves and beautifully textured bark. Learn more inside.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

River Birch-Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue University Fort Wayne

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

In this edition of ID That Tree, meet River Birch. As its name implies, it is often found near waterways and in moist soil areas across the state of Indiana. It can be multi-stemmed, often in landscaping, or single stemmed, often in woodlands and bottomlands. Simple triangular-shaped leaves with doubly-serrated margins and flaking/peeling bark are key identifiers. In younger trees, the bark peels more and can range from chalky white to reddish brown. Bark on older trees is darker gray/brown and peeling is less prominent.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources YouTube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR YouTube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

River Birch-Native Trees of Indiana River Walk, Purdue University Fort Wayne

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

In this edition of ID That Tree, learn how to tell Red Hickory apart from its cousins shellbark, shagbark and pignut hickory. Located typically in upland dry sites, red hickory stands out with compound leaves with seven leaflets, long running interlacing gray bark, buds and twigs free of hairs, and lastly nuts with a husk that separates all the way down the sides of the nut.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources Youtube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR Youtube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

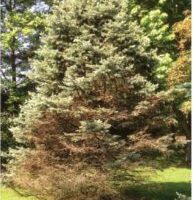

Purdue Landscape Report – Tip Blights of Juniper: Junipers have to be my favorite group of evergreens, behind a select few pine species. They have a fantastic fragrance, are evergreen, many can tolerate drought, are an ingredient in gin (definitely a bonus), and work well in a variety of landscape uses, including as a barrier plant. They look great year round, except when they have tip blight.

Tip blight is a common disease in nurseries and landscapes that cause branch tips to die back fairly quickly starting in the spring. Infected branches become chlorotic, progressing from light green to yellow, before turning brown as the season continues. Black fungal structures will develop in the transition zone between affected foliage and green, healthy tissue. Some of the infected scales may turn gray in color, surrounding these structures.

Two fungi cause tip blight, Kabatina and Phomopsis, and knowing which one you have is important to determine your management strategies. Both fungi produce similar symptoms and similar fungal structures,

so the presence of tiny black dots cannot help separate these diseases. Both fungi also infect a range of hosts, including arborvitae, cypress, Douglas fir, true firs, yew, Cryptomeria, and Chamaecyparis, but these are not as susceptible as juniper species.

Kabatina infects young, new growth during the growing season, but infected twigs remain green until winter and the following spring . . .

Resources:

Borers of Pines and Other Needle Bearing Evergreens in Landscapes, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Ask an Expert Question: Blue Spruce dying, what can I do?, Got Nature? Blog, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources

Why Spruce Trees Lose Their Needles, Purdue Extension

Diseases Common in Blue Spruce, Purdue Extension

Purdue University Invasive Species

John Bonkowski, Plant Disease Diagnostician

Purdue Botany and Plant Pathology

This native tree comes with its own defense system in very large thorns on the stems and trunk. Meet the honey locust. Purdue Extension forester Lenny Farlee explains that large, long yellow seed pods that resemble bean pods, the option of single or doubly compound leaves on the same tree and smooth gray bark also help identify this species.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources Youtube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR Youtube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

This native Indiana tree species is found in three southwestern counties near the lower Wabash River. It is often found in wet or ponded locations where there is standing water or high water tables. Meet water locust. It has large multi-pronged thorns and compound leaves like its cousin the honey locust, but can be differentiated by its location, its much smaller seed pods and its flattened thorns along the branches.

If you have any questions regarding wildlife, trees, forest management, wood products, natural resource planning or other natural resource topics, feel free to contact us by using our Ask an Expert web page.

Resources:

ID That Tree, Playlist, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources Youtube Channel

A Woodland Management Moment, Playlist, Purdue Extension – FNR Youtube Channel

Shrubs and Woody Vines of Indiana and the Midwest, The Education Store, Purdue Extension Resource Center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

If you have ever noticed acorns so numerous that you could not take a step without crushing several, you may be asking the question, “why are there so many acorns?” Some answers to this question can be found in the physiology and ecology of trees and their relationship to wildlife. Oaks and several other tree species occasionally produce enormous crops of seed. This is called “masting” or “mast events”. These events are periodic. In the case of many oak species, a large mast event may happen every two to five years, depending on the species of oak and several other factors. Masting events may be preceded and followed by small or moderate acorn crops, or complete crop failures in some cases. Why does this irregular seed production happen? These events may be tied to several aspects of the life of oaks.

First, the production of a huge volume of a large seed like an acorn requires a lot of resources from the tree. This level of production may not be possible for the tree every year. Trees allocate energy to several different functions, so committing large amounts of energy to one area could mean deficits in others. This may mean there are advantages for the tree to produce occasional, rather than annual, mastings.

Second, weather does not always cooperate to provide the conditions for a bumper acorn crop. Unfavorable weather during pollination and seed development periods can result in reduced production of acorns. Late spring freezes, extremely high temperatures, summer droughts and other weather stresses can reduce acorn pollination and production.

Third, predation by seed-eaters like squirrels, deer, turkey and even weevil larvae can greatly reduce the number of viable acorns. It may take a very large acorn crop to have many acorns escape from the numerous species that depend on acorns for food.

This irregular cycle of large crops can be beneficial for the oaks by overwhelming the seed eaters. Populations of wildlife that depend on acorns may eat most of the seed during normal seed crops, but may not be able to utilize all the seed produced during a masting. This surplus seed is available produce the next generation of oak seedlings.

However, some species will produce copious amounts of the mast if the developmental age of the tree is favorable, regardless of conditions.

Acorn production can vary by species and individual trees across the oak family, but masting is a way this important group of trees can continue to be a part or our Midwestern landscape.

Resources:

Woodland Management Moment: Direct Seeding, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Ask an Expert: Tree Selection and Planting, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) YouTube Channel

Forest Improvement Handbook, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Native Trees of the Midwest, The Education Store

Investing in Indiana Woodlands, The Education Store

Tree Pruning Essentials, The Education Store

Lenny Farlee, Sustaining Hardwood Extension Specialist

Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources

Lindsey Purcell, Chapter Executive Director and Certificate Liaison

Indiana Arborist Association

Purdue Landscape Report: Colorado blue spruce is not native to Indiana (no spruce is!), and it often suffers from environmental stresses such as drought, excessive heat, humidity, and compacted or heavy clay soils—making it an already poor choice for our landscape. If that weren’t enough, it also suffers from needle cast diseases. Needle cast is a generic term that refers to foliar diseases of coniferous plants that result in the defoliation (“casting off”) of needles. Needle casts vary by host, and severity is dependent upon the age of infected needles. Of all the foliar diseases affecting woody landscape plants and shrubs, needle casts are the most serious for the simple reason that coniferous plants do not have the ability to refoliate, or produce a second flush of needles from defoliated stems. Rhizosphaera needle cast is a fungal disease, caused by Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii that attacks the needles of Colorado blue spruce in the spring, as new needles emerge. However, infected needles often don’t show symptoms right away, and may take one to three years to develop. Infected needles later turn purple to brown and fall from the tree prematurely (Fig. 1), leaving the inner portion of the branch bare.

As the disease progresses, severely infected branches die, leaving the tree with a hollow or thin appearance (Fig. 2). The disease usually starts near the base of the tree where humidity levels are the highest but continues to spread upward. As the disease continues, trees become unsightly and lose their value as a visual screen or privacy fence.

The Rhizosphaera pathogen sporulates in the spring (Fig. 3), which is the best time to control this disease. The fungal fruiting structures emerge on these needles and are usually large enough to be visible to the eye, with the fruiting structures appearing as rows of small dots running lengthwise along the white bands of the needles. In severe infections, trees may only have the current year’s needles remaining rather than the 5- to 7-year complement of needles a healthy spruce maintains. Destructive epidemics of needle casts or rusts are not uncommon and develop under periods of extended leaf wetness. The after-affect of these epidemics can persist for several years. In the urban setting, needle casts are more of an endemic, as most conifers are ill-suited to the Midwest urban environment. Most conifers retain their needles for two to seven years. The length of time that a needle is retained depends on the species of coniferous plant and if the plant has been subjected to stress such as drought, flooding, salt damage, disease, or insect pest. Trees that lack the full complement of needles are stressed or undergoing pest attack. When attempting to determine the cause of needle drop, examine the branch carefully to determine if the problem is normal needle drop, the yearly occurrence on normal needle shedding. The newest needles should not be affected and problems should not appear within the last two to three years of growth.

Managing Rhizosphaera: there are conifers that are more resistant to Rhizosphaera, and include white spruce (P. glauca) and its variant Black Hills spruce, both of which are intermediate in resistance. Norway spruce (P. abies) is highly resistant to this disease. Some Colorado blue spruce cultivars, like ‘Hoopsii,’ and ‘Fat Albert’ are reportedly more resistant to the disease.

Spectro-90, or copper-based fungicide, can protect new growth and prevent new infections; Concert II, Heritage, Pageant, and Trinity are labeled for use in commercial and residential landscapes, and nurseries, but data regarding their efficacy is lacking for this disease. Daconil Weatherstik is not labeled for blue spruce in the landscape but is still available for use in the nursery and for other landscape diseases.

It is important to protect new growth as it emerges no matter which fungicide you apply; fungicides should be applied when the new needles are half elongated (late April or early May) and again three to four weeks later, possibly with a third application if wet weather or growth persists. Rhizosphaera needle cast may be controlled in one year if fungicides are applied correctly. However, severely infected trees usually require two or more years of fungicide applications. Even though fungicide application will effectively control this disease, reinfection may occur in subsequent years. Application to large trees requires special equipment to ensure adequate coverage. Read fungicide labels carefully and apply only as directed.

When planting new trees, consider planting Norway or white spruce, which are more resistant to Rhizosphaera. Other spruce, like Serbian, simply haven’t had widespread evaluation in the Midwest, so buyer beware! Properly spacing spruce trees will help reduce disease incidence. Spruce trees grow best in moderately moist, well-drained soils but can be planted in other soils if adequate moisture is available. Avoid heavy clay, as trees planted on these sites often suffer iron, magnesium, and manganese deficiency. Water newly planted trees, and water during drought periods to help maintain tree vigor and minimize stress. Stressed trees should also be mulched and fertilized as needed. Properly prune dead or severely infected branches during dry weather. If trees are severely infected, the lower whorl of branches may also be removed to help increase air circulation.

Article originally published by the Indian Nursery & Landscape Association Magazine, March/April 2018. www.inla1.org

Resources:

Needlecast in Colorado Blue Spruce, Purdue Landscape Report

Blue Spruce Update, Purdue Landscape Report

Why Spruce Trees Lose Their Needles, Purdue Extension

Blue Spruce Decline, Purdue Extension

Ask an Expert Question: Blue Spruce dying, what can I do?, Purdue Extension – Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) Got Nature? Blog

Tree Installation: Process and Practices, The Education Store, Purdue Extension resource center

Tree Planting and Urban Forestry Videos, Subscribe to our Purdue Extension-FNR YouTube Channel

Janna Beckerman, professor

Purdue Botany and Plant Pathology

Recent Posts

- ID That Tree: Fragrant Sumac

Posted: February 4, 2026 in Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - Tree Silvics and Succession Webinar: A Biological Basis for Management

Posted: January 30, 2026 in Forests and Street Trees, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Southwest Damage, Scalding or Frost Cracking

Posted: in Forestry, Urban Forestry - A Woodland Management Moment: Wide Spacing for Nut Production

Posted: January 29, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Woodland Management Moment, Woodlands - Woodsy Owl Edition for Educational Learning, USDA – U.S. Forest Service

Posted: January 21, 2026 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Got Nature for Kids, Urban Forestry, Wildlife - ID That Tree: Trumpet Creeper

Posted: January 20, 2026 in Forests and Street Trees, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Indiana Woodland Steward Newsletter, The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment

Posted: January 7, 2026 in Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - FNR Extension Offering Forest Management for the Private Woodland Owner Course in Spring 2026

Posted: January 5, 2026 in Forestry, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands - A Woodland Management Moment: Black Walnut in Pine Plantation

Posted: December 19, 2025 in Forestry, Forests and Street Trees, Urban Forestry, Woodlands - Red in Winter – What Are Those Red Fruits I See?

Posted: December 1, 2025 in Forestry, Plants, Urban Forestry, Wildlife, Woodlands

Archives

Categories

- Alert

- Aquaculture/Fish

- Aquatic/Aquaculture Resources

- Ask the Expert

- Christmas Trees

- Community Development

- Disease

- Drought

- Forestry

- Forests and Street Trees

- Gardening

- Got Nature for Kids

- Great Lakes

- How To

- Invasive Animal Species

- Invasive Insects

- Invasive Plant Species

- Land Use

- Natural Resource Planning

- Nature of Teaching

- Plants

- Podcasts

- Ponds

- Publication

- Safety

- Spiders

- Timber Marketing

- Uncategorized

- Urban Forestry

- Webinar

- Wildlife

- Wood Products/Manufacturing

- Woodland Management Moment

- Woodlands