From Waste to Resource: A Student’s Journey to Recover the Metal Compounds That Power Our Future

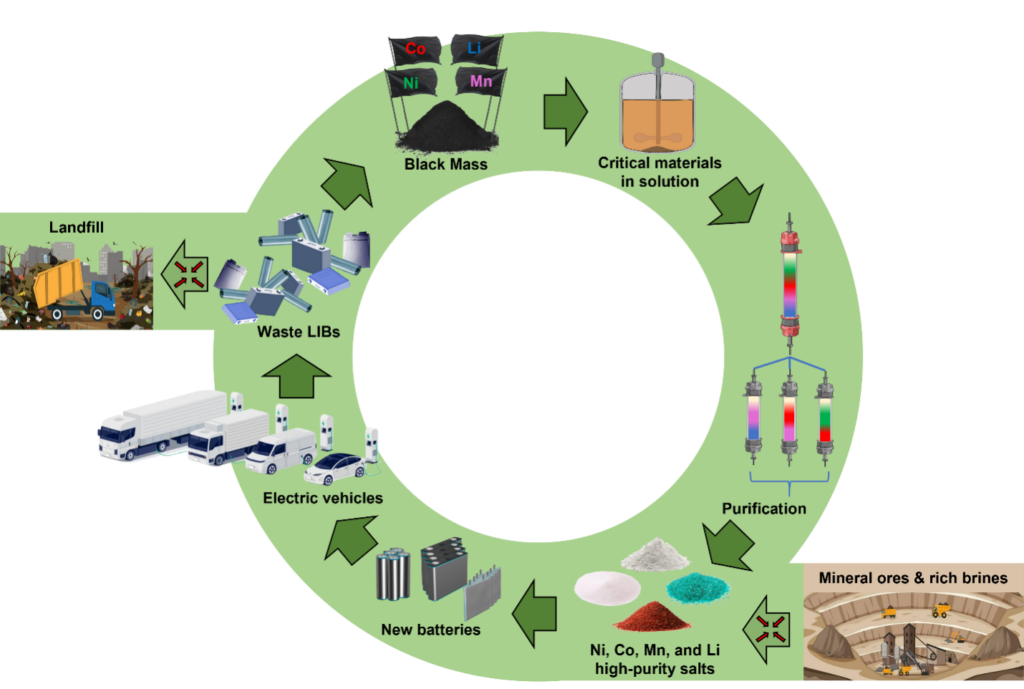

The clean energy revolution has a hidden problem: billions of electric vehicle batteries are on a countdown to die. Each car carries hundreds to thousands of battery cells, and with nearly 20 million EVs already on the road, that adds up to an enormous wave of waste approaching the end of its ten-year lifespan. Without a solution, these batteries will pile up in landfills, turning a symbol of progress into a new environmental crisis.

Picture that mountain of discarded batteries: silent, heavy, and full of wasted potential. Inside lies a treasure of lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese, the elements that make modern energy storage possible. If we fail to recover them, they will not power the next generation of clean technology. Instead, they will sit as toxic pollution, undermining the very promise of electrification.

This looming dilemma became the starting point of my research journey at Purdue University. As a Ph.D. student in chemical engineering, I asked myself a simple question: could a lab technique I had used countless times, chromatography, be reimagined to tackle one of the world’s biggest sustainability challenges? My goal was not just to create a brand-new recycling process. It was to rethink how we handle battery waste before it buries the clean energy transition under its own success.

Chromatography is a separation technique usually confined to the lab bench, separating tiny samples for analysis. But I wondered: what if we scaled it up? Could it recover metal compounds from the messy “black mass” left after electric vehicle batteries are shredded? Black mass is a dark, powdery mix that holds lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and impurities all tangled together. To most people, it looks like waste. To me, it looked like an opportunity.

Working with my team, I designed a process that sends dissolved black mass through a resin column. Much like runners in a race, each element moves at its own pace. Lithium pulls ahead, nickel lags behind, cobalt and manganese drift apart, and what begins as a chaotic mixture emerges as high-purity salts. What was once a problem becomes a resource ready to be fed back into new batteries.

The first time I saw these sharp separation bands form, I knew this method could change the story of recycling. It was not just effective in the lab. It was scalable. Through careful design, simulation, and experimentation, we proved the process could be expanded without losing efficiency, delivering purities above 99.5 percent while keeping yields above 99 percent. That level of performance means the recovered materials are good enough to go straight into battery manufacturing. What began as an experiment has now grown into patents, licensed technology, and pilot-scale trials. Today, a large-scale plant based on this process is under construction in Indiana, setting the stage for industrial adoption.

For me, this work is more than a technical achievement. It is a vision of a circular economy where yesterday’s waste becomes tomorrow’s resource. By recovering lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese from discarded batteries, we can reduce the pressure on mining, cut environmental damage, and keep clean energy technologies truly sustainable. Mining these elements is costly, energy-intensive, and often devastating for local communities. Recycling can change that equation. It means less digging into the earth and more smart use of what we already have.

As I look ahead, I see more than columns and chemical equations. I see a choice. If we do nothing, landfills will grow into toxic monuments to the clean energy transition. If we succeed, those same mountains of waste will transform into renewable sources of the metal compounds that keep our world moving. The clean future we imagined is still possible. But it depends on whether we are willing to see waste not as an ending, but as the beginning of something new.

About the Author:

Gabriel Perez Schuster is a Ph.D. student in the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering at Purdue University. His research focuses on developing chromatography-based methods to recycle critical materials from complex mixtures, advancing the circular economy and sustainable energy solutions. He recently received first place for Best Oral Presentation among the graduating Ph.D. class of chemical engineers at the 34th GSO Symposium at Purdue. Outside the lab, Gabriel contributes to sustainability and safety committees and actively engages with the community through art and service.

Want to participate in the competition?