Effect of Social Pressure and Wealth Disparity on Resilience in Post-Disaster Debris and Waste Management

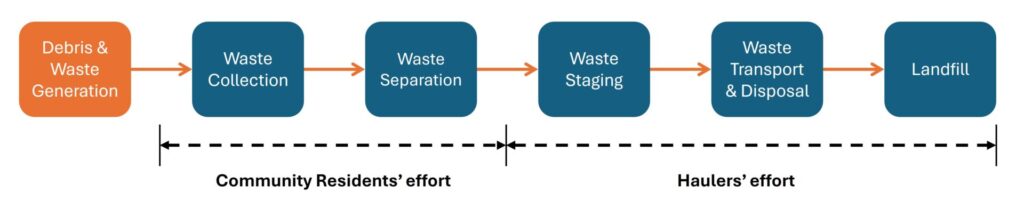

Climate change is intensifying and increasing the frequency of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires. In their wake, communities are left with massive amounts of debris—a mixture of destroyed buildings and various types of waste. This debris can paralyze a city’s functions and poses a major obstacle, preventing residents from resuming their daily lives. Therefore, prompt and efficient management of this waste is a critical part of disaster recovery. Figure 1 shows the conventional disaster waste management process.

My research examines the impact of social pressure and wealth disparity on community resilience in post-disaster waste management. The research question is, “How do unseen social and economic factors influence the debris management process in communities?” My study examines whether variables such as social pressure among residents and economic disparities between wealthier and poorer communities can lead to significant differences in recovery speed. I also investigated why poorer areas often recover more slowly than wealthier ones and whether the strategic placement of waste staging sites can incentivize recovery in these communities without direct financial investment.

To analyze the complex interactions considering various factors, I used a simulation technique called a dynamic model. This model uses mathematical equations to show how a situation evolves over time, allowing me to predict the interactions and outcomes resulting from the behavioral changes of various entities. The model I designed includes the following key variables: (1) Residents’ Participation (Social Pressure): This reflects how an individual’s decision to help with sorting the debris is influenced by their neighbors’ actions. The model captures the real-world phenomenon where, as more people participate, the social pressure for others to join in also grows. (2) Economic Incentives (Wealth Disparity): Wealthier communities can often pay waste removal contractors more, allowing them to secure more trucks or haulers. I simulated how this financial advantage can lead to an unequal pace of recovery between communities. (3) Physical Distance: The distance between an affected area and its temporary waste staging site is a crucial logistical factor. A longer distance means more travel time and higher fuel costs for trucks, making the operation less efficient. This variable was also taken into account in the design of the dynamic model.

I conducted my analysis using two main scenarios in a hypothetical community. The first scenario examined the effect of “social pressure” on disaster recovery participation within a single community. This study examined the impact of social pressure intensity on the speed of recovery among residents. The results were striking! In a scenario with strong social pressure, most residents voluntarily participated in the debris sorting process over time, and all debris was cleared in approximately 90 days. Conversely, in a scenario with weak social pressure, the number of participants became lower, and recovery took around 280 days after the same disaster. This clearly shows how powerful community cooperation and mutual encouragement can be in accelerating disaster recovery, even without direct government intervention.

The second scenario examined the effects of “economic disparities” between wealthier and poorer communities and “the effect of the location of the temporary waste staging site”. Initially, I modeled a situation where the wealthier community paid haulers a higher rate. As a result, haulers, seeking greater profit, directed more of their trucks to the wealthy community, which completed its recovery in 60 days. However, the poorer community suffered from the removal of debris due to a lack of economic incentives, and the process took significantly longer.

However, when temporary waste staging sites were installed near the poorer community, a significant and interesting reversal occurred. Haulers began sending more trucks to the poorer community to reduce travel distances and save on fuel costs. As a result, the poorer community recovered much faster than the wealthier one. This suggests that efficient infrastructure deployment can be just as crucial as economic incentives for increasing equity in recovery.

The conclusions and policy recommendations of this study are as follows. Using a dynamic modeling approach, this study clearly demonstrates that disaster recovery is not simply a matter of financial incentives. Based on the analysis, I propose the following policies. First, to increase the effectiveness of disaster recovery, local governments should actively utilize social/local media to encourage voluntary participation from the community’s residents and thereby build positive social pressure. Second, even if subsidies cannot be provided to economically distressed areas, strategically deploying temporary waste staging sites can mitigate the inequality in recovery speed caused by wealth disparities.

This study has limitations, as it is based on a simplified model of real-world situations. Nevertheless, it conveys an important message: disaster recovery policies should take into account not only financial support, but also community-based factors such as social pressure. Furthermore, the effective deployment of infrastructure can serve as a means to reduce social disparities.

About the Author:

Seungik is a Ph.D. student in the Lyles School of Civil and Construction Engineering at Purdue University. He began his doctoral studies in 2023. Prior to graduate school at Purdue, Seungik completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in civil & environmental engineering at Yonsei University, South Korea. Currently, his research focuses on community resilience and disaster recovery, with a particular emphasis on how social and economic factors impact disaster management. Using dynamic modeling and simulation, he investigates the roles of social pressure, wealth disparities, and infrastructure placement in shaping the speed and equity of recovery. After completing his Ph.D., Seungik hopes to continue advancing research and policy development that promote resilient and equitable communities in the face of climate change.

Want to participate in the competition?