Aging Without Forgetting: What fuels the brains of resilient Alzheimer’s disease individuals?

Alzheimer’s disease has devastated families for over a century. It was first identified in 1906 by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who examined the brain of a patient suffering from severe memory loss, paranoia, and confusion. He discovered strange buildups of proteins now known as plaques and tangles, which have since become the classic hallmarks of the disease, alongside its devastating symptoms. Yet more than 100 years later, there is still no cure.

Alzheimer’s isn’t just memory loss. It’s a slow deterioration of the brain’s ability to store and form new experiences. It gradually erodes the very essence of who we are, until one day, someone may no longer recognize their own name, their loved ones, or even themselves. It’s heartbreaking. And it’s more common than most people realize. By age 65, about one in twenty people has Alzheimer’s disease. By 75, it’s one in eight and by 85, one in three. Those are chilling numbers, and they show why this research is more urgent than ever.

While much of the current research in this area focuses on why people get Alzheimer’s, our research takes a different approach. Instead of asking why some people get Alzheimer’s, we ask: Why don’t others?

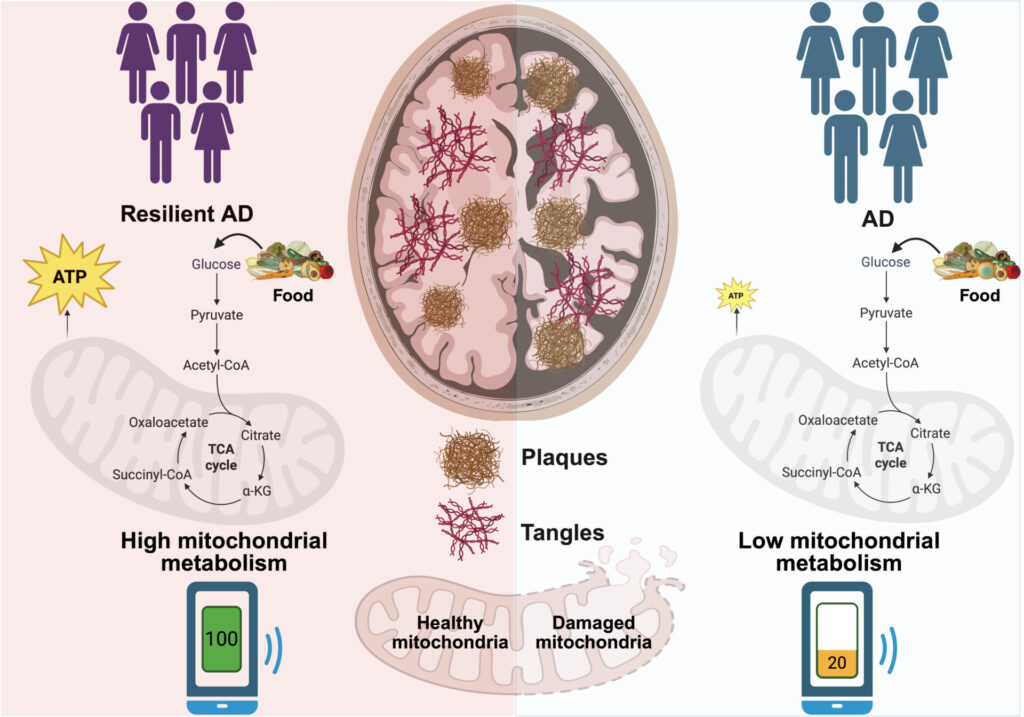

There’s a fascinating group of individuals we call “resilient.” These people lived long lives with no signs of memory loss or cognitive decline. They remained active, sharp, and mentally intact. But when they passed away and donated their brains to science, researchers discovered something shocking: their brains were filled with the same plaques and tangles seen in those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

For decades, traditional research has focused on removing these sticky proteins, spending years and millions of taxpayer dollars in the process. Yet most treatments have failed. In many cases, clearing plaques did not improve memory at all, and often caused severe side effects that led to the drug’s discontinuation. These failures have forced scientists to reconsider the root of the problem.

So, what if we’ve been asking the wrong question? What if the key isn’t getting rid of the bad, but preserving what works? These resilient individuals had the same disease-related changes but no symptoms. That means something in their biology was protecting them.

When we compared their brains to those who developed Alzheimer’s symptoms, we found a striking difference in a place many of us first learned about in high school biology: the mitochondria, often called the “powerhouse of the cell.” Mitochondria take the food we eat, carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, and convert them into energy. Every action our brain performs, from remembering the name of a loved one to solving a crossword puzzle, depends on that energy.

In resilient brains, mitochondrial function was preserved. The complex machinery needed to convert food into energy remained intact. Mitochondria rely on five protein complexes to generate this energy. Think of them like a hydroelectric dam. Complexes I through IV act like pumps, building pressure by moving protons, like how a dam stores water behind its wall. Then comes Complex V, ATP synthase: the turbine. It spins as protons flow back through it, using that mechanical motion to generate the energy our cells need. In resilient brains, this energy-generating system was still working. In Alzheimer’s brains, it had already begun to fail.

This may sound simple, but it’s profound. It means that even when plaques and tangles are present, brain energy systems might hold the line. When mitochondria break down, the brain starts losing power like a phone with a dead battery. Even if the hardware is perfectly fine, if the battery is gone, the phone won’t turn on. The same could be true for our brains.

So, if resilient individuals were able to keep their mitochondria healthy well into old age, can we do the same?

The good news is that mitochondria respond to lifestyle. They are strengthened by exercise, good nutrition, and metabolic balance. The same things doctors recommend for our heart, like movement, sleep, and eating well, also support our brain’s energy engine. So, while there’s no miracle cure for Alzheimer’s yet, we may be getting closer to something just as powerful: prevention or at least delay by learning from those who resisted the disease.

Our research, and that of a few others in this new wave of Alzheimer’s science, is beginning to shift the conversation. Instead of only asking what went wrong, we’re now asking what went right and how can we recreate it? The stories hidden inside resilient brains teach us that aging doesn’t have to mean forgetting. By preserving energy, we may preserve identity, connection, and conserve brain functions that resist forgetting.

About the Author:

Purba Mandal is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the PULSe program at Purdue University, working in Dr. Priyanka Baloni’s lab in the College of Health Sciences with a focus on Integrative Neuroscience. She hold a B.Sc. and M.Sc. in Chemistry from St. Xavier’s College and the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur, India respectively. Prior to joining Purdue, she interned in a neurology clinic, where she gained firsthand experience with patients and developed a strong interest in neuroscience. At Purdue, she is the recipient of the 2023 PIIN Organoid Grant and was awarded first place in oral presentation for her research on resilient Alzheimer’s disease at the 2025 Biomedical Engineering Symposium. She also received a Top 10 Poster Award at the 2025 HSCI Annual Research Retreat.

Want to participate in the competition?