Nurses provide patients’ perspective to engineers

Written by Marti LaChance

When nursing student Nathan Bryan found himself discussing needle exchange programs with Lafayette Mayor Tony Roswarski, it really sank in.

“It was my first experience seeing that I can be a catalyst for change, that I can have a voice in policymaking,” says Bryan, a senior. “You read about it in textbooks, and they tell about it in lectures. But meeting with the mayor, I realized: ‘Wow, this is a lot bigger than me. This is awesome’ — which pretty much sums up my sentiment about this project.”

Supercharging leadership

The project — a joint effort by nursing and biomedical engineering students — stemmed from a curricular innovation devised by nursing professors Diane Hountz and Pam Karagory, who now heads the Purdue School of Nursing.

Hountz, who frequently mentors biomedical engineering students, realized that nursing students, with their patient-centric training, could provide valuable insights into the medical device development process.

“I knew we needed to find a way to merge nursing students with engineering students — to see how together we can provide better outcomes for patients in our health care system,” Hountz says.

In Purdue’s Leadership in Nursing course, nursing seniors are paired with local health care practice partners to learn how to solve systems health care problems. Students apply the quality improvement principles they’ve studied to solve real-world problems. Hountz and Karagory thought: Why not pair our nurses with biomedical engineers working on medical devices?

Purdue biomedical engineering students have a Senior Design course in which they develop a device to solve a real-world medical problem. Nurses and engineers seemed natural collaborators. Hountz and Karagory broached the idea of collaborative projects with Asem Aboelzahab, lab and assessment coordinator for the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering.

Aboelzahab immediately saw value in the proposal: “We thought engineering students could help the nursing students figure out if their ideas about a device were feasible from an engineering standpoint. And the nursing students could help the engineers tailor their product to the market and gather user feedback — to verify if the device had clinical viability.

For the 2018-19 school year, the faculty-staff team came up with two device development projects that would especially benefit from a multidisciplinary approach.

“Our big overarching goal is to improve health care,” Hountz says. “We want to optimize each other’s strengths, improve patient safety and to improve patient outcomes.”

Partners tackle Parkinson’s

One of the projects was a device for Parkinson’s disease patients to track the progression of tremor symptoms, which are notoriously difficult to quantify. At the semester’s outset, the student team brainstormed and determined that a toothbrush was the perfect tool for measuring tremors. People hold the object in their hands and they use it every day. The tremor data could be downloaded and patients could take it to their physician appointments. They dubbed the device TREMM.

While the biomedical engineering students were developing sensors, devising a method for recording the data and configuring a charging station for the device, the nursing students’ task was to interview medical professionals familiar with Parkinson’s patients. Nursing senior Sarah Kincade was part of the team.

“Members of the Nursing faculty gave us feedback about things we should be taking into account. For example, Parkinson’s disease patients have tremors more dominantly in one hand than the other, so users would need to use the same hand consistently when brushing their teeth,” Kincade says. “But faculty also said, on the whole, they thought it sounded like a great idea.”

The project also impressed the judges; in December 2018 at the Weldon School’s Senior Design Projects Presentations and Demonstrations event — they awarded the TREMM team second place for its innovative product for Parkinson’s patients.

Needle exchange challenge

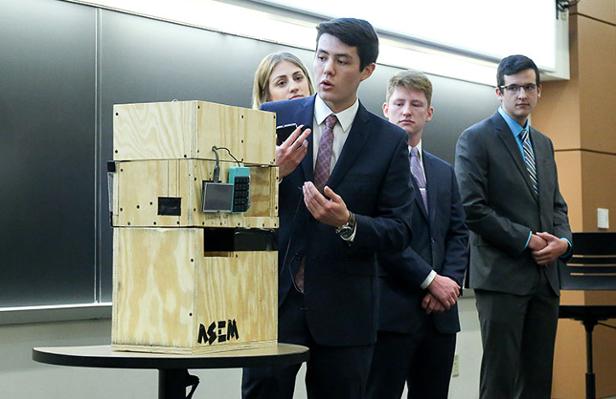

The other project, which BME students have been working on for several semesters, was the Automated Syringe Exchange Machine, or ASEM, a device for automating the needle exchange process. The engineers understood that many needle exchange programs were underfunded and short-staffed, so an automated solution made sense. A hands-free syringe exchange device also would reduce the risk of needle sticks.

The idea was for health departments to deploy the device for reducing needle-borne illnesses like HIV and hepatitis C. The box, outfitted with artificial intelligence and sensors, detects the presence of a syringe, or syringes, and dispenses the same number of clean ones.

Upon joining the needle exchange project, the nursing students immediately questioned the project scope. They wondered, for instance, how such a device would affect its target patients, IV drug users.

“Right away we brought a more humanitarian perspective to the project,” says nursing student Tianna Stieglitz, who, like many other people in the U.S., has been personally affected by the opioid epidemic. “It is not just about reducing disease transmission; we also want to potentially help these people.”

Steiglitz says she was surprised at the engineers' lack of understanding of the prospective patient. “They knew a lot about the technical side and had done quite a bit of research on public policy, but they didn’t really understand the ramifications of needle exchange,” she says. “We had a big-picture approach they didn’t have. That’s what we brought to the table.”

Researching the feasibility of the syringe-dispensing device, the nursing students learned plenty. For one thing, because heroin is illegal, they couldn’t interview drug users. Nevertheless, the students sought input from local community stakeholders and from the Tippecanoe County Health Department, which had recently implemented a syringe services program (SSP), in August 2017.

From health care professionals who interact with drug users, the nursing students learned that human interactions are vital for needle exchange programs. It is during these personal dealings with addicts that health care workers can offer medical help and resources for drug-treatment programs.

“I think we definitely helped the engineers realize that the problem is much larger than just disease transmission,” Bryan says. “There’s the mental health aspect to it. There’s a whole law enforcement aspect to it. The list of people affected just goes on and on.

“So, one of the barriers with this machine is that it would take away that face-to-face interaction,” Bryan adds. “Due to the various roadblocks, we decided that this machine would best serve as a gateway for setting up a syringe service program.”

Ultimately, the students’ research led all the way to city hall — and the City of Lafayette mayor’s office. The nurses and engineers met with Mayor Tony Roswarski and presented a policy brief detailing the reality of the local illicit IV drug crisis and the challenges that exist in Tippecanoe County.

Roswarski was open to the students’ ideas and provided vital feedback for the engineers designing the device. Although his current stance is against needle exchange programs, the mayor and the students had a constructive conversation. In December 2018, Tippecanoe County commissioners voted to allow the syringe exchange program to operate for another year.

Groundwork for nursing careers

Stieglitz says the experience working on the syringe exchange device prepared her for the realities of her career.

“It made me really rethink how I approach addiction in clinical practice,” Stieglitz says. “I am thankful that I had the opportunity to study it before actually being in clinical practice.”

For Bryan, working with engineers and getting involved with community policymaking expanded his view of the nursing profession.

“It was a great way to work as a member on an interdisciplinary team,” he says. “Interacting with people with different majors, different disciplines — it forced me to communicate in ways I haven’t before, forced me out of my comfort zone.”

The syringe dispensing device is still under development and about 70 percent complete. Although the nursing students’ portion of the project is formally over, Bryan hopes to stay abreast with the project until he graduates.

Improved curriculum, improved health care

For Purdue’s nursing and engineering faculty, it was clear that the collaborations were valuable for all concerned. The faculty team is planning for another set of team projects in spring and fall 2019.

Lab coordinator Aboelzahab reports that from the engineering perspective, the collaboration helped students get key feedback from clinical students and faculty.

“In the past, one of the biggest struggles for our students has been getting the right feedback from stakeholders,” he says. “By collaborating with nurses, engineering students will be able to really hone the scope of their senior design projects.”

For nurses, the joint projects are one more way to improve health care.

“We want our students to ask: ‘How are we helping the patient? How are we helping the health care system by providing this device?’” Hountz says. “It was such an eye-opening experience for both sets of students. We all need to work together as a team to provide better solutions to health care challenges encountered by our patients and move our health care system forward.”