More than machines: Computer scientist prepares robots to improve human lives

Robots to help with aphasia, cancer care, geriatric issues and more

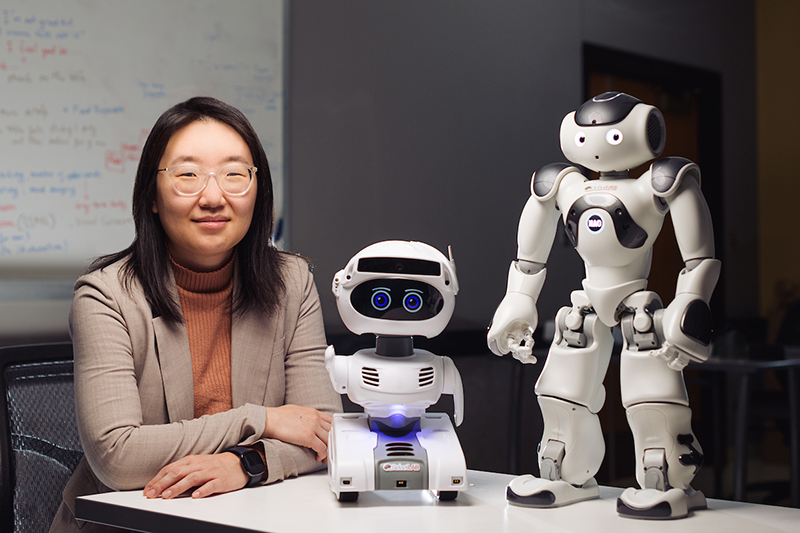

Robot expert Sooyeon Jeong and her lab work to make robots a force for good in human life and society. (Purdue University photo/Becky Robiños)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. —

There is no avoiding robots. With increasing autonomy, satellites span the skies; vacuums vroom underfoot; and bots conduct surgery, deliver packages and explore the solar system.

Robot expert Sooyeon Jeong, an assistant professor of computer science in Purdue University’s College of Science, works in artificial intelligence to ensure that those robots are more friendly helpers to humans and less inscrutable interlopers, more R2-D2 than HAL, more Baymax than Terminator.

“My goal, and the goal of my research group, is to design robots and AI that can have socially and emotionally natural interactions with people,” Jeong said. “I want anything I make or design to have a measurable positive impact on people’s lives.”

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

To that end, she has created social robots for hospitalized children and is working on robots to help stroke patients recover their power of speech, a virtual avatar that empowers Latinas in Greater Lafayette and in Chicago to learn about their cancer diagnoses, and robots whose goal is to improve human health and life. Watch her discuss her goals and research — alongside her robots — in this video.

I, for one, welcome our new robot … health care providers

Robots, or virtual agents, are an excellent choice for jobs that would be dangerous, expensive, difficult or time-consuming for humans.

Take, for example, people who have lost their power of speech after having a stroke or brain injury, a condition called aphasia. To recover their speech, they need hours of intensive speech therapy and practice every day. But they often don’t have that much access to a speech therapist. That’s where a robot can come in.

A robot can focus completely on being present for the person, on repeating words as often as necessary. It never gets bored, never gets impatient and says words the exact same way every single time. If a robot speech therapist can reside in patients’ homes and provide daily support, patients might progress much more quickly when they can get in to see their human speech therapist. Jeong’s lab is collaborating with Purdue’s Aphasia Research Laboratory to explore solutions.

“Robots aren’t a replacement for speech therapists, or for anyone,” Jeong said. “But they can fill the gap between what’s available to patients and what the patients need. That’s what our research is currently addressing: Can social robots provide a similar level of engagement and intervention effects as a human can or could?”

Another project aims to help Latinas with breast cancer in the Greater Lafayette and Chicago areas. Collaborating with Francisco Iacobelli at Northeastern Illinois University, who is a Latino professor of computer science, Jeong is creating a virtual agent that can engage in judgment-free conversations with Latina breast cancer survivors and help them improve their health literacy.

The virtual agent fills the role of a knowledgeable confidant — someone it’s impossible to embarrass, and someone who can patiently and correctly give out medical information, help flag what symptoms could be problematic, and encourage patients when they need to contact their doctors.

“We wanted them to be able to have something more like a peer, a nonjudgmental voice they can have conversations or interactions with to help inform them and reinforce their knowledge,” Jeong said. “To do that, we really have to understand their language and culture to be able to put them at ease and help effectively.”

Computer communication

The first computers were the size of rooms and required humans to communicate with them with hole-punched notecards. From there, machines evolved to communicate via binary code and keyboards, while a new generation of AI agents, computer programs and other robots communicate with a more organic, natural language. Jeong envisions a future where robots incorporate social and emotional cues into their communication, as well as adapting to respond to nonverbal and tonal cues.

To a layperson, the word “robot” conjures images of a physical creation — something that moves, rolls or otherwise interacts with the physical world. However, computer scientists also work with robots that occupy a more virtual world, including virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Iron Man’s J.A.R.V.I.S. Jeong’s research works with both. She uses whatever mode she thinks will best fit the problem being addressed.

“I’m very interested in people who are left out of current support systems,” Jeong said. She collaborates with other scientists across a range of fields that include audiology, psychology, medicine, public health and gerontology. Her collaborators help identify problems that her robots and virtual assistants could offer solutions to.

“I realized that many of these machines — robots and AI — they are designed in a lab,” she said.“But there are all these differences between the real world and the lab. I wanted to focus on developing robots that can interact with people and help them in real-life settings.”

In fact, one of the first projects Jeong worked on as a doctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was presaged by her interests in robots as a child.

“When I was around 11, I watched ‘AI’ by Steven Spielberg, and I was fascinated by the teddy robot. It wasn’t telling the protagonist what to do; it was a more supportive role. It was acting a little like Jiminy Cricket from ‘Pinocchio,’ nudging the character to make better decisions, being a sort of confidant,” she said. “I saw that, and I just remember thinking, ‘Oh, I would love to have something like that for myself.’ And so I ended up working on something similar, developing a teddy bear robot for very, very sick hospitalized kids in pediatric hospitals.”

Helping robots read the room

Putting people at ease is a huge hurdle for robots. While many humans innately talk to and anthropomorphize inanimate objects, creating a robot that is both trustworthy and helpful is something researchers are still working on.

When a friend asks how you’re doing, there is a vast distance between “Fine,” with a weary tone, slumped shoulders and a sigh, and “Fine!” with a grin and an upbeat tone. To many computers, those two answers would be identical. They contain the exact same letters in the exact same order. But a human with social intelligence can easily discern the difference.

Teaching machines to do the same can help them help humans. After all, sometimes the message of the dejected “fine” is actually much more nuanced. Sometimes it really means, “Not at all fine, but I’m tired and dispirited and don’t want to bother anyone with it, but if you’re really interested, I would be glad to talk.” The latter message would be vital to a robot assigned with helping, for example, a child with emotional turbulence or a senior citizen with medical issues.

Jeong explains that robots don’t just need to listen to what a person is saying; they need to engage in active listening. They need to mirror behavior and tone and understand how to react and respond.

“When you are talking to another person, there is so much communication going on that is not verbal,” Jeong said. “They’re nodding, smiling, encouraging you to continue, signaling that they’re listening. They’re also gauging what appropriate reactions are. I realized the robot I developed during graduate school had these shortcomings, these gaps in the interaction. People who were conversing with this robot were sharing all these thoughts — a whole story — with the robot, and it said, ‘Thanks for sharing!’ and then moved on. That kind of interaction doesn’t help foster a long-term relationship that can potentially benefit the human.”

Jeong envisions a future where robots and virtual agents can work alongside humans, assisting with physical therapy, tutoring, encouraging independence, and supporting people in living happy and healthy lives.

“These robots and AI agents really need social and emotional intelligence to really help people at the right time and in the right way,” she said. “For instance, robots tasked with helping people be productive or safe should be able to gauge when to interrupt otherwise busy people, when to proactively engage them and ask questions. If an undergrad student needs a study buddy, the robot needs to be able to assess their feelings and figure out when they’re stressed and need a break or when they’re distracted and need help turning off YouTube Shorts and getting back on track.”

Not only do robots need to be able to read humans, but they also need to be approachable and have the right morphology for each application context. For example, would older adults find it more helpful and engaging during a speech therapy session if a robot had humanlike facial features or a cartoonlike face with big arm gestures? Jeong and her lab are investigating the impact of a robot’s design on people’s trust and sense of comfort to avoid the eerie “uncanny valley” effect, in which the robot is too human and not human enough all at the same time.

In her previous research, Jeong designed robots to look small and cute, like dogs or toys, so even a sick child in a hospital could approach, and not ones that too closely mimic human body language and facial expressions.

“As robots become more available in people’s daily lives, we need to make sure they’re helping in real ways, long term, in the real world,” Jeong said.

This work is part of Purdue’s One Health initiative, and AI is a foundational component of the Institute for Physical Artificial Intelligence, a Purdue Computes initiative.

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a public research institution demonstrating excellence at scale. Ranked among top 10 public universities and with two colleges in the top four in the United States, Purdue discovers and disseminates knowledge with a quality and at a scale second to none. More than 105,000 students study at Purdue across modalities and locations, including nearly 50,000 in person on the West Lafayette campus. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue’s main campus has frozen tuition 13 years in a row. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap — including its first comprehensive urban campus in Indianapolis, the new Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. School of Business, and Purdue Computes — at https://www.purdue.edu/president/strategic-initiatives.

Writer/Media contact: Brittany Steff, bsteff@purdue.edu

Source: Sooyeon Jeong