November 13, 2018

If at first your diet fails, try again. Your heart will thank you

Diet fluctuations lead to a rollercoaster of risk for heart disease and diabetes

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — During the holiday season, it can be difficult for even the most determined of us to stick to a healthy diet. A piece of Halloween candy here, a pumpkin spice latte there, and suddenly we’re left feeling like we forgot what vegetables taste like.

Our weight isn’t the only aspect of our health that can fluctuate during times like these. According to a new article in the journal Nutrients, risk factors for cardiovascular disease closely track with changes in eating patterns, even only after a month or so.

Research led by Wayne Campbell shows risk factors for cardiovascular disease closely track changes in eating patterns. (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

Download image

Research led by Wayne Campbell shows risk factors for cardiovascular disease closely track changes in eating patterns. (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

Download image

“If you’re inconsistent about what kinds of foods you eat, your risk factors for developing these diseases are going to fluctuate,” said Wayne Campbell, a professor of nutrition science at Purdue University. “Even in the short term, your food choices influence whether you’re going to have a successful or unsuccessful visit with your doctor.”

Diet failure isn’t an anomaly, it’s the norm, and there are a variety of reasons for that. This can lead to repetitive attempts of adopting, but not maintaining, healthy eating patterns.

To assess how these diet fluctuations affect risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, such as blood pressure and cholesterol, Campbell’s team looked to two previous studies (also led by Campbell at Purdue). The research study participants adopted either a DASH-style eating pattern (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) or a Mediterranean-style eating pattern.

“Our DASH-style eating pattern focused on controlling sodium intake, while our Mediterranean-style focused on increasing healthy fats,” said Lauren O’Connor, the lead author of the paper. “Both eating patterns were rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains.”

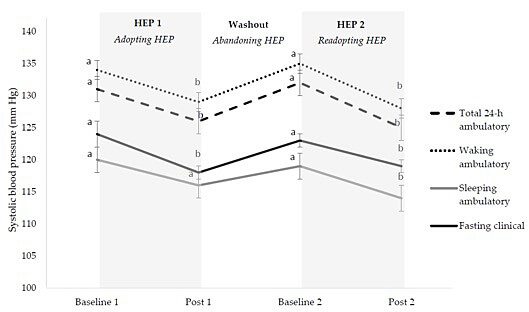

Blood pressure falls and rises as study participants adopt and abandon healthy eating patterns.

Blood pressure falls and rises as study participants adopt and abandon healthy eating patterns.

Participants adopted a healthy eating pattern for five or six weeks and then had their risk factors measured. The study participants then returned to their normal eating patterns for four weeks and came back for a checkup. After adopting a healthy eating pattern again for another five or six weeks, participants had their risk factors assessed one last time.

The results look almost exactly as you’d expect: like a cardiovascular rollercoaster. How fast the participants’ health started to improve after adopting a healthier diet is impressive, though. It only takes a few weeks of healthy eating to generate lower blood pressure and cholesterol.

“These findings should encourage people to try again if they fail at their first attempt to adopt a healthy eating pattern,” Campbell said. “It seems that your body isn’t going to become resistant to the health-promoting effects of this diet pattern just because you tried it and weren’t successful the first time. The best option is to keep the healthy pattern going, but if you slip up, try again.”

The long-term effects of adopting and abandoning healthy eating patterns on cardiovascular disease are unknown. Research on weight cycling suggests that when people who are overweight repeatedly attempt to lose weight, quit, and try again, that may be more damaging to their long-term health than if they maintained a steady weight. To know if long-term health effects of cycling between eating patterns raise similar concerns, further studies are needed.

The work aligns with Purdue's Giant Leaps celebration, acknowledging the university’s global advancements made in health, longevity and quality of life as part of Purdue’s 150th anniversary. This is one of the four themes of the yearlong celebration’s Ideas Festival, designed to showcase Purdue as an intellectual center solving real-world issues.

Researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of Colorado contributed to this work. The studies were funded by the Pork Checkoff, the Beef Checkoff, with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Clinical Research Center.

Writer: Kayla Zacharias, 765-494-9318, kzachar@purdue.edu

Sources: Wayne Campbell, 765-494-8236, campbellw@purdue.edu

Lauren O’Connor, leoconno@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: For a copy of the paper, please contact Kayla Zacharias, Purdue News Service, kzachar@purdue.edu.

ABSTRACT

Short-term effects of healthy eating pattern cycling on cardiovascular disease risk factors: pooled results from two randomized controlled trials

Lauren E. O’Connor, Jia Li, R. Drew Sayer, Jane E. Hennessy, Wayne W. Campbell

Adherence to healthy eating patterns (HEPs) is often short-lived and can lead to repetitive attempts of adopting—but not maintaining—HEPs. We assessed effects of adopting, abandoning, and readopting HEPs (HEP cycling) on cardiovascular disease risk factors (CVD-RF). We hypothesized that HEP cycling would improve, worsen, and again improve CVD-RF. Data were retrospectively pooled for secondary analyses from two randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trials (n = 60, 51 ± 2 years, 30.6 ± 0.6 kg/m2) which included two 5–6 week HEP interventions (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension-style or Mediterranean-style) separated by a four-week unrestricted eating period. Ambulatory and fasting blood pressures (BP), fasting serum lipids, lipoproteins, glucose, and insulin were measured before and during the last week of the HEP interventions. Fasting systolic BP and total cholesterol decreased (−6 ± 1 mm Hg and −19 ± 3 mg/dL, respectively, p < 0.05), returned to baseline, then decreased (−5 ± 1 mm Hg and −13 ± 3 mg/dL, respectively, p < 0.05) when adopting, abandoning, and readopting HEP; magnitude of changes did not differ. Ambulatory and fasting diastolic BP and HDL followed similar patterns; glucose and insulin remained unchanged. LDL decreased with initial adoption but not readoption (−13 ± 3 and −6 ± 3, respectively, interaction p = 0.020). Healthcare professionals should encourage individuals to consistently consume a HEP for cardiovascular health but also encourage them to try again if a first attempt is unsuccessful or short-lived.