Office of Engagement’s

Protocol

Engagement is the collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity (Carnegie Foundation, 2008). It is a way to dynamically empower communities to address issues, opportunities, or needs through ongoing partnerships with higher education. Engagement also enhances and enriches discovery and learning outcomes by bringing relevance resulting in societal impacts. Societal impacts are changes or benefits beyond academia to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, and the environment or quality of life because of research, teaching, or engagement. In other words, engagement is one of the mechanisms—in addition to discovery and teaching—through which the land grant mission is fulfilled. The land grant mission compels universities to serve their state, region, nation, and world.

The Philosophy

University Engagement activities must follow these principles1

Mutually agreed upon sets of goals, operating principles, and expectations.

Clarity of communication, leadership, power sharing, and decision-making.

Promotion of active and representative participation.

Sustained commitment, collaboration, and willingness to learn and grow together while working toward the long-term sustainability and well-being of the community.

Investment of time and money and/or other needed resources to bring about community capacity building and leadership enhancement.

Active and respectful engagement of communities in learning and understanding community issues and the economic, social, environmental, political, psychological, and other impacts associated with alternative courses of action.

Outcomes

Broader Impacts in Research

Federal agencies and other university funders are expanding research proposal requirements around community engagement and broader impacts, calling for increasingly detailed and meaningful strategies, plans, and metrics. This research, sometimes but not exclusively community-based, results in relevance and involves the documentation, evaluation, and communication of its broader impacts.

Scholarship of Engagement

The scholarship of engagement (SoE) is a reciprocal relationship with communities that yields innovations with disciplinary expertise, documents evidence of impact, can be replicated, and is professionally and/or peer reviewed. In other words, it is a process by which scholars communicate to, and work both for and with, communities. Providing services to communities that fill gaps, e.g. healthcare, education, employment, can be a form of SoE when the process involves teaching, learning, and/or discovery initiatives that lead to capacity building, and other societal impacts.

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

The scholarship of teaching of learning (SoTL) involves instructors, sometimes in partnership with their students, undertaking systematic inquiry into student learning gains. This work yields innovations with disciplinary expertise, documents evidence of impact, can be replicated, and is professionally and/or peer reviewed. Implementing service-learning in the classroom may result in student learning gains, relevance to instruction, jobs, and world readiness, e.g., preparation for engaged citizenship, as well as societal impacts.

Dynamic Empowerment Engagement2

Not all societal impacts are tied exclusively to research or teaching and learning, but still leverage university knowledge, expertise, and resources to empower communities. They also evaluate, document, communicate and disseminate their impact. Examples include increasing awareness of local, regional, or national issues through data collection, analysis, and insights; facilitating community strategic planning; forming/supporting partnerships to address complex issues; regional, community, economic, or workforce development; or empowering communities through capacity-building.

Activities

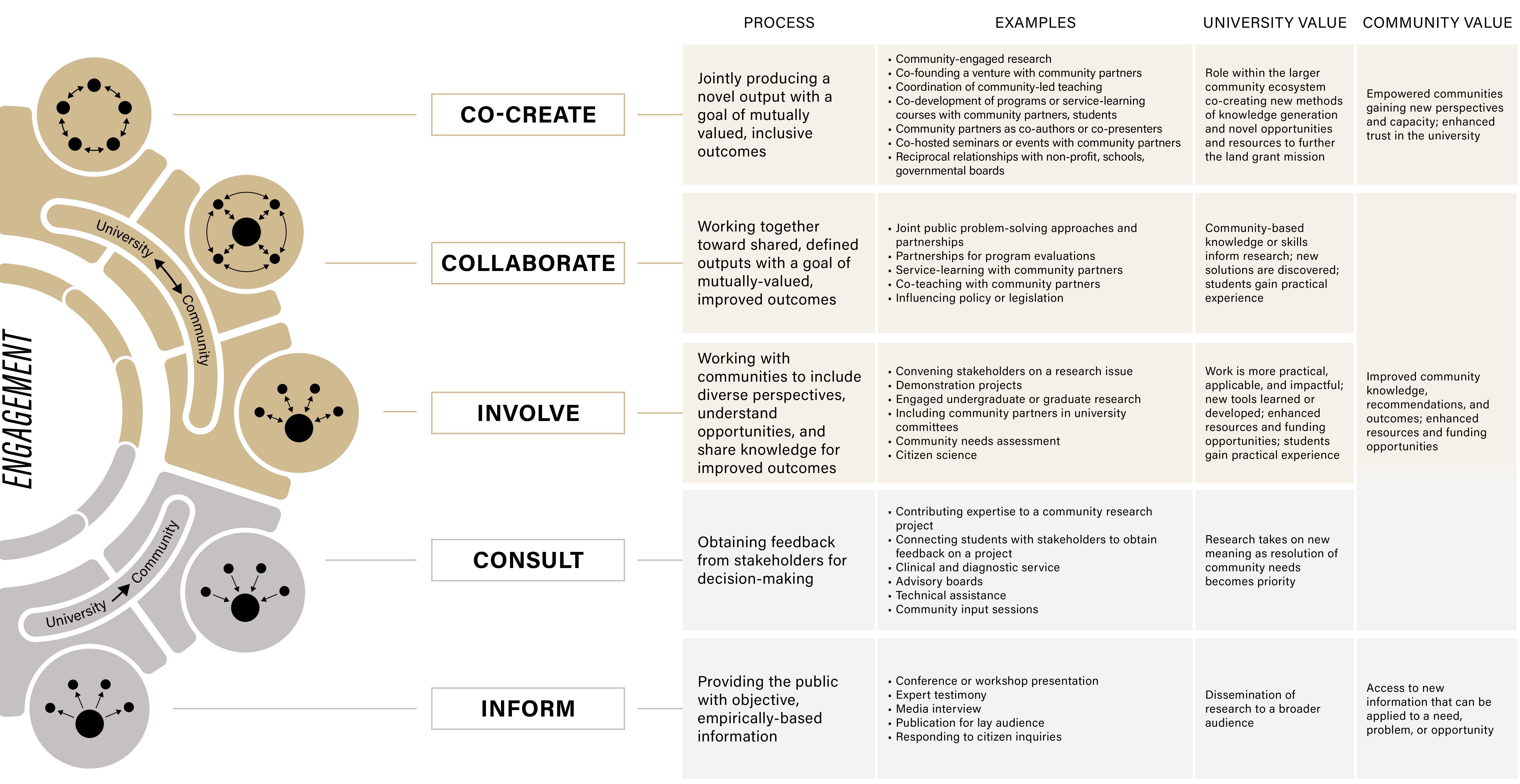

There are many different types of engagement activities.

The examples discussed below are not meant to be comprehensive3, but rather include examples with progressively increasing levels of engagement with external partners and communities: inform, consult, involve, collaborate, co-create. Some activities may contribute to engaged scholarship while others may focus primarily on enhancing research broader impacts, student learning gains, or community empowerment.

Ultimately, all activities should follow the Engagement Principles listed above and result in societal impacts that strengthen trust, build capacity, and increase the university’s relevance among the larger community. Engagement activities not included are industry fundraising and student recruitment, as they do not align with the societal impact focus.

On Ramps

These on-ramps are distinguished for illustration purposes but overlap significantly in practice.

Research With Broader Implications

Including community-based research.

K-12 Outreach

With research, professional development, or capacity-building objectives. (i.e. VetaHumanz)

Experiential Education

Clinical and diagnostic service, Service-Learning, EPICS, etc.

Dynamic Empowerment

Including capacity-building, technical assistance, planning, etc.

Purdue Extension

Including 4-H, agricultural and natural resources, community development, and health and human science

Developing Engaged Partnerships

Like all successful relationships, engaged partnerships take time and energy to truly grow into mutually beneficial, reciprocal partnerships.

Determining what is required to build and sustain successful partnerships is challenging and takes time, because each collaboration requires unique considerations and elements to achieve these results.

It is critical to be honest and transparent with community partners about your interests, intentions, assets, constraints, and expected outcomes. Ask questions; listen hard; be flexible. Recognize there are many kinds of expertise in the world and many kinds of strengths; honor your collaborators’ expertise and leverage their strengths.

It is also critical to assess partnerships at each stage of the partnership; doing so will enhance your understanding of how collaborative efforts evolve and are sustained. Equally important, your findings can be published as models of mutually beneficial, reciprocal engaged partnerships. Both the university and the partner need to see benefit for the partnership to be successful.

Building Relationships and Clarifying Expectations

Share goals and clarify expectations – interests, intentions, assets, constraints, expected outcomes, time commitments, research expectations, student learning goals, governance, etc.

Establish a communication plan, e.g., contact frequency and platform.

Discuss funding, other resources needs, research opportunities, and IRB as needed.

Finalizing Commitments and Implementing

Complete appropriate forms and share with all partners – research contracts, Institutional Review Board (IRB), syllabus, learning contract, etc.

Implement the engaged work respecting plans, milestones, partner needs, etc.

Conduct frequent, scheduled check-ins with partner.

Monitoring, Assessing, and Celebrating Partnerships

Meet with partners to evaluate and adjust the engagement efforts as needed.

Conduct evaluation and assessment of the engaged partnership, including partners, stakeholders, and students, as applicable.

Host partnership debriefs with all partners and continue to steward partner relationships.

Develop and disseminate work.

Celebrate and communicate the accomplishments of the engaged partnership.

Additional Resources

Promotion and Tenure

The pathway to promotion and tenure based on the scholarship of engagement is well documented at Purdue. Resources are available to help junior faculty draft engagement dossiers (identify community partners, their roles, scholarly portfolio, and impact) and to help senior faculty evaluate them. The Guide is a valuable resource for this work.

Professional Development

Engagement can be incorporated into faculty and staff work across any of the other two mission areas. Instructors interested in engaging with communities through teaching and learning can participate in the Service-learning Fellows program. Fellows learn proper service-learning pedagogy, are paired with a community partner, and learn to evaluate the impact of engagement on student learning while meeting community needs. Support for faculty and staff interested in integrating engagement within their research portfolios is available. Please contact the Office of Research if interested. This technical support integrates community engagement with intellectual merit in a fully integrated approach within grant proposals.

Publication Outlets

Engaged scholars may be interested in publishing the impact of their community partnerships within peer-reviewed literature that extends beyond their disciplinary expertise. The OoE has procured a large list of engagement publication outlets scholars can consider disseminating their engaged scholarly contributions.

Awards

Rewards and recognition are important indicators of outstanding achievement for the university’s engaged scholars. Internal awards are one method of faculty recognition for engagement work including scholarship. The OoE coordinates both internal and external/national award recognition for faculty and staff.

Footnotes

1

Bringle et al., 2009; Campus Community Partnerships for Health, 2006; Community Development Society’s Principles of Good Practice; Enos & Morton, 2003

2

Meintjes, Garth (1997). Human Rights Education as Empowerment: Reflections on Pedagogy. In G.J. Andreopoulos & R.P. Claude (eds.), Human Rights Education for the Twenty-First Century. University of Pennsylvania Press.

3

Adapted from the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) and Colorado State University