'Microring' device could aid in future optical technologies

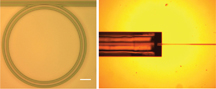

Researchers have created a tiny "microring resonator," at left, small enough to fit on a computer chip. The device converts continuous laser light into numerous ultrashort pulses, a technology that might have applications in more advanced sensors, communications systems and laboratory instruments. At right is a grooved structure that holds an optical fiber leading into the device. (Birck Nanotechnology Center, Purdue University)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers at Purdue University and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have created a device small enough to fit on a computer chip that converts continuous laser light into numerous ultrashort pulses, a technology that might have applications in more advanced sensors, communications systems and laboratory instruments.

"These pulses repeat at very high rates, corresponding to hundreds of billions of pulses per second," said Andrew Weiner, the Scifres Family Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The tiny "microring resonator" is about 80 micrometers, or the width of a human hair, and is fabricated from silicon nitride, which is compatible with silicon material widely used for electronics. Infrared light from a laser enters the chip through a single optical fiber and is directed by a structure called a waveguide into the microring.

The pulses have many segments corresponding to different frequencies, which are called "comb lines" because they resemble teeth on a comb when represented on a graph.

By precisely controlling the frequency combs, researchers hope to create advanced optical sensors that detect and measure hazardous materials or pollutants, ultrasensitive spectroscopy for laboratory research, and optics-based communications systems that transmit greater volumes of information with better quality while increasing bandwidth. The comb technology also has potential for a generation of high-bandwidth electrical signals with possible applications in wireless communications and radar.

The light originates from a continuous-wave laser, also called a single-frequency laser.

"This is a very common type of laser," Weiner said. "The intensity of this type of laser is constant, not pulsed. But in the microring the light is converted into a comb consisting of many frequencies with very nice equal spacing. The microring comb generator may serve as a competing technology to a special type of laser called a mode-locked laser, which generates many frequencies and short pulses. One advantage of the microrings is that they can be very small."

The laser light undergoes "nonlinear interaction" while inside the microring, generating a comb of new frequencies that is emitted out of the device through another optical fiber.

"The nonlinearity is critical to the generation of the comb," said doctoral student Fahmida Ferdous. "With the nonlinearity we obtain a comb of many frequencies, including the original one, and the rest are new ones generated in the microring."

Findings are detailed in a research paper appearing online this month in the journal Nature Photonics. The paper is scheduled for publication in the Dec. 11 issue.

Although other researchers previously have demonstrated the comb-generation technique, the team is the first to process the frequencies using "optical arbitrary waveform technology," pioneered by Purdue researchers led by Weiner. The researchers were able to control the amplitude and phase of each spectral line, learning that there are two types of combs - "highly coherent" and "partially coherent" - opening up new avenues to study the physics of the process.

"In future investigations, the ability to extract the phase of individual comb lines may furnish clues into the physics of the comb-generation process," Ferdous said. "Future work will include efforts to create devices that have the proper frequency for commercial applications."

The silicon-nitride device was fabricated by a team led by Houxun Miao, a researcher at NIST's Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology and the Maryland Nanocenter at the University of Maryland. Some of the work was performed at the Birck Nanotechnology Center in Purdue's Discovery Park, and experiments demonstrating short-pulse generation were performed in Purdue's School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The effort at Purdue is funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the Naval Postgraduate School.

Writer: Emil Venere, 765-494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: Andrew Weiner, 765-494-5574, amw@purdue.edu

Houxun Miao, 301-975-8499, hmiao@nist.gov

Note to Journalists: An electronic copy of the research paper is available by contacting Nature at press@nature.com

Related websites:

Ultrafast Optics and Optical Fiber Communications Laboratory

ABSTRACT

Spectral Line-by-Line Pulse Shaping of an On-Chip

Microresonator Frequency Comb

Fahmida Ferdous, 1Houxun Miao, 2,3* Daniel E. Leaird,1 Kartik Srinivasan,2 Jian Wang,1,4 Lei Chen,2 Leo Tom Varghese,1,4 and Andrew M. Weiner 1,4*

1School of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Purdue University

2 Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology,

National Institute of Standards and Technology

3 Maryland Nanocenter, University of Maryland

4 Birck Nanotechnology Center, Purdue University

Recently, on-chip comb generation methods based on nonlinear optical modulation in ultrahigh quality factor monolithic microresonators have been demonstrated, where two pump photons are transformed into sideband photons in a four wave mixing process mediated by the Kerr nonlinearity. Here we investigate line-by-line pulse shaping of such combs generated in silicon nitride ring resonators. We observe two distinct paths to comb formation which exhibit strikingly different time domain behaviors. For combs formed as a cascade of sidebands spaced by a single free spectral range (FSR) that spread from the pump, we are able to stably compress to nearly bandwidth-limited pulses. This indicates high coherence across the spectra and provides new data on the high passive stability of the spectral phase. For combs where the initial sidebands are spaced by multiple FSRs which then fill in to give combs with single FSR spacing, the time domain data reveal partially coherent behavior.