Nanowick at heart of new system to cool 'power electronics'

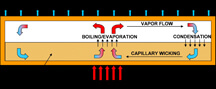

This diagram depicts a cooling device called a heat pipe, used in electronics and computers. Researchers are developing an advanced type of heat pipe for high-power electronics in military and automotive systems. The system is capable of handling roughly 10 times the heat generated by conventional computer chips. The miniature, lightweight device uses tiny copper spheres and carbon nanotubes to passively wick a coolant toward hot electronics. (School of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers have shown that an advanced cooling technology being developed for high-power electronics in military and automotive systems is capable of handling roughly 10 times the heat generated by conventional computer chips.

The miniature, lightweight device uses tiny copper spheres and carbon nanotubes to passively wick a coolant toward hot electronics, said Suresh V. Garimella, the R. Eugene and Susie E. Goodson Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Purdue University.

This wicking technology represents the heart of a new ultrathin "thermal ground plane," a flat, hollow plate containing water.

Similar "heat pipes" have been in use for more than two decades and are found in laptop computers. However, they are limited to cooling about 50 watts per square centimeter, which is good enough for standard computer chips but not for "power electronics" in military weapons systems and hybrid and electric vehicles, Garimella said.

The research team from Purdue, Thermacore Inc. and Georgia Tech Research Institute is led by Raytheon Co., creating the compact cooling technology in work funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA.

The team is working to create heat pipes about one-fifth the thickness of commercial heat pipes and covering a larger area than the conventional devices, allowing them to provide far greater heat dissipation.

New findings indicate the wicking system that makes the technology possible absorbs more than 550 watts per square centimeter, or about 10 times the heat generated by conventional chips. This is more than enough cooling capacity for the power-electronics applications, Garimella said.

The findings are detailed in a research paper appearing online this month in the International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer and will be published in the journal's September issue. The paper was written by mechanical engineering doctoral student Justin Weibel, Garimella and Mark North, an engineer with Thermacore, a producer of commercial heat pipes located in Lancaster, Pa.

"We know the wicking part of the system is working well, so we now need to make sure the rest of the system works," North said.

The new type of cooling system can be used to prevent overheating of devices called insulated gate bipolar transistors, high-power switching transistors used in hybrid and electric vehicles. The chips are required to drive electric motors, switching large amounts of power from the battery pack to electrical coils needed to accelerate a vehicle from zero to 60 mph in 10 seconds or less.

Potential military applications include advanced systems such as radar, lasers and electronics in aircraft and vehicles. The chips used in the automotive and military applications generate 300 watts per square centimeter or more.

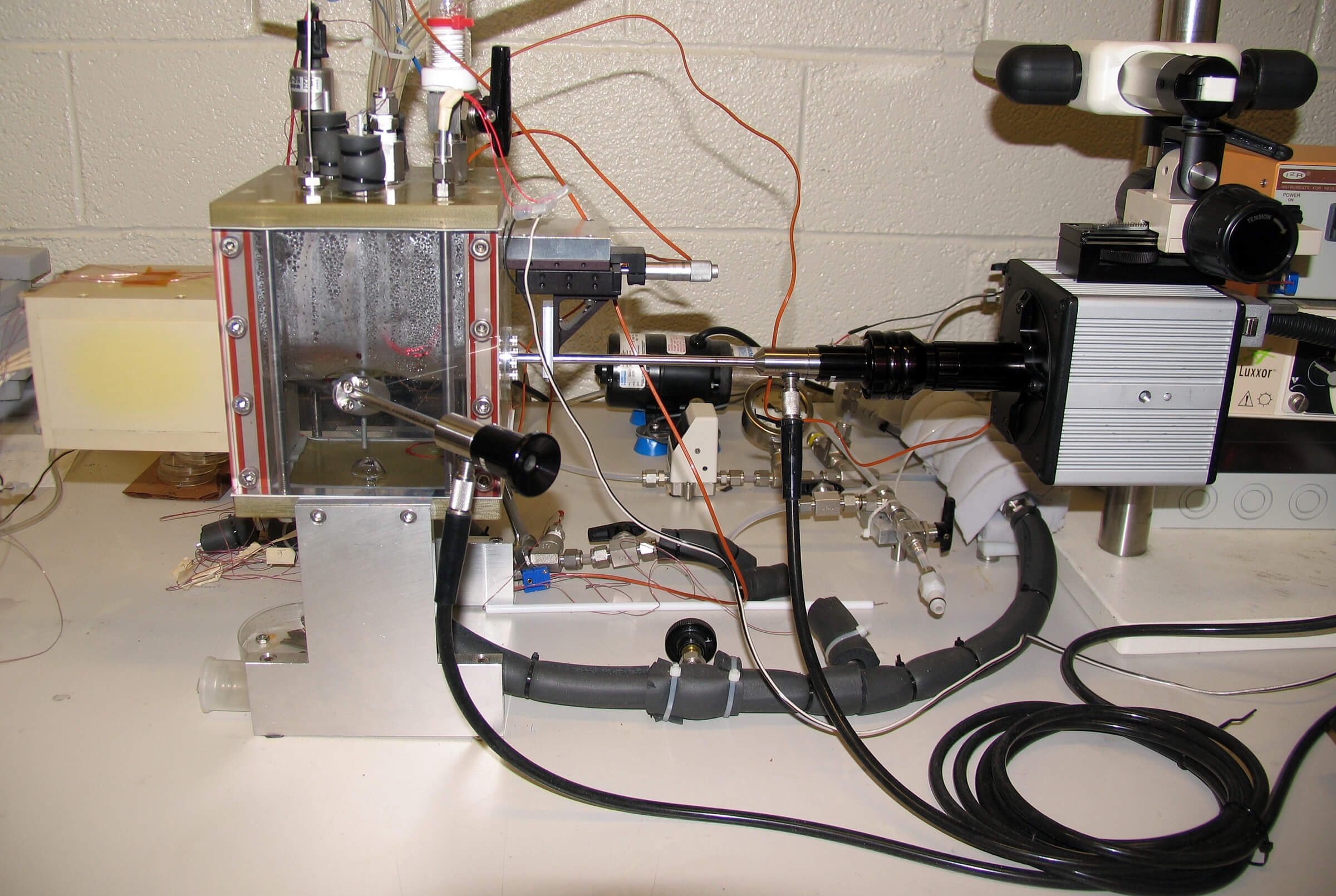

Researchers are studying the cooling system using a novel test facility developed by Weibel that mimics conditions inside a real heat pipe.

"The wick needs to be a good transporter of liquid but also a very good conductor of heat," Weibel said. "So the research focuses largely on determining how the thickness of the wick and size of copper particles affect the conduction of heat."

Computational models for the project were created by Garimella in collaboration with Jayathi Y. Murthy, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering, and doctoral student Ram Ranjan. The carbon nanotubes were produced and studied at the university's Birck Nanotechnology Center in work led by mechanical engineering professor Timothy Fisher.

"We have validated the models against experiments, and we are conducting further experiments to more fully explore the results of simulations," Garimella said.

Inside the cooling system, water circulates as it is heated, boils and turns into a vapor in a component called the evaporator. The water then turns back to a liquid in another part of the heat pipe called the condenser.

The wick eliminates the need for a pump because it draws away fluid from the condenser side and transports it to the evaporator side of the flat device, Garimella said.

Allowing a liquid to boil dramatically increases how much heat can be removed compared to simply heating a liquid to temperatures below its boiling point. Understanding precisely how fluid boils in tiny pores and channels is helping the engineers improve such cooling systems.

The wicking part of the heat pipe is created by sintering, or fusing together tiny copper spheres with heat. Liquid is drawn sponge-like through spaces, or pores, between the copper particles by a phenomenon called capillary wicking. The smaller the pores, the greater the drawing power of the material, Garimella said.

Such sintered materials are used in commercial heat pipes, but the researchers are improving them by creating smaller pores and also by adding the carbon nanotubes.

"For high drawing power, you need small pores," Garimella said. "The problem is that if you make the pores very fine and densely spaced, the liquid faces a lot of frictional resistance and doesn't want to flow. So the permeability of the wick is also important."

The researchers are creating smaller pores by "nanostructuring" the material with carbon nanotubes, which have a diameter of about 50 nanometers, or billionths of a meter. However, carbon nanotubes are naturally hydrophobic, hindering their wicking ability, so they were coated with copper using a device called an electron beam evaporator.

"We have made great progress in understanding and designing the wick structures for this application and measuring their performance," said Garimella. He said that once ongoing efforts at packaging the new wicks into heat pipe systems that serve as the thermal ground plane are complete, devices based on the research could be in commercial use within a few years.

Writer: Emil Venere, (765) 494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: Suresh Garimella, (765) 494-5621, sureshg@purdue.edu

Justin Weibel, jaweibel@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: An electronic copy of the research paper is available from Emil Venere, 765-494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

ABSTRACT

Characterization of Evaporation and Boiling from Sintered Powder Wicks Fed by Capillary Action

Justin A. Weibel a, Suresh V. Garimella a*, Mark T. North b

a

b Thermacore, Inc.,

The thermal resistance to heat transfer into the evaporator section of heat pipes and vapor chambers plays a dominant role in governing their overall performance. It is therefore critical to quantify this resistance for commonly used sintered copper powder wick surfaces, both under evaporation and boiling conditions. The objective of the current study is to measure the dependence of thermal resistance on the thickness and particle size of such surfaces. A novel test facility is developed which feeds the test fluid, water, to the wick by capillary action. This simulates the feeding mechanism within an actual heat pipe, referred to as wicked evaporation or boiling. Experiments with multiple samples, with thicknesses ranging from 600 to 1200 lm and particle sizes from 45 to 355 lm, demonstrate that for a given wick thickness, an optimum particle size exists which maximizes the boiling heat transfer coefficient. The tests also show that monoporous sintered wicks are able to support local heat fluxes of greater than 500Wcm 2 without the occurrence of dryout. Additionally, in situ visualization of the wick surfaces during evaporation and boiling allows the thermal performance to be correlated with the observed regimes. It is seen that nucleate boiling from the wick substrate leads to substantially increased performance as compared to evaporation from the liquid free surface at the top of the wick layer. The sharp reduction in overall thermal resistance upon transition to a boiling regime is primarily attributable to the conductive resistance through the saturated wick material being bypassed.