Study gives clearer picture of how land-use changes affect U.S. climate

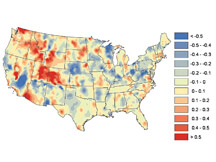

This map shows observation minus reanalysis (OMR) trends in the continental United States from 1979-2003. The trends are associated with land use and land-use changes. Researchers from Purdue and the universities of Colorado and Maryland conducted a study that showed land use can affect surface temperatures locally and regionally. Units are in degrees Celsius per decade. (Image courtesy of Souleymane Fall)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers say regional surface temperatures can be affected by land use, suggesting that local and regional strategies, such as creating green spaces and buffer zones in and around urban areas, could be a tool in addressing climate change.

A study by researchers from Purdue University and the universities of Colorado and Maryland concluded that greener land cover contributes to cooler temperatures, and almost any other change leads to warmer temperatures. The study, published on line and set to appear in the Royal Meteorological Society’s International Journal of Climatology later this year, is further evidence that land use should be better incorporated into computer models projecting future climate conditions, said Purdue doctoral student Souleymane Fall, the article’s lead author.

“What we highlight here is that a significant trend, particularly the warming trend in terms of temperatures, can also be partially explained by land-use change,” said Dev Niyogi, a Purdue earth and atmospheric sciences and agronomy professor, and the Indiana state climatologist. He is the study's corresponding author.

Niyogi and Fall say the idea that land use helps drive climate change has been poorly understood compared to factors such as greenhouse gas emissions. But that is changing.

“People realize that land use cover also is an important force and not only at the local but also at the regional scale,” said Fall, whose doctoral research focuses on the impacts of land surface properties on near-surface temperature trends.

The researchers used higher resolution temperature data than previous studies, meaning the data was more detailed, Niyogi said. They also employed dynamic data on land-use changes from 1992-2001, which was derived from satellite imagery.

Niyogi said having an understanding of land use's affects on climate change could have climatic and other benefits. For instance, creating green spaces and buffer zones in and around urban areas also could be aesthetically attractive, he said.

Among the study's findings:

* In general, the greener the land cover, the cooler is surface temperature.

* Conversion to agriculture results in cooling, while conversion from agriculture generally results in warming.

* Deforestation generally results in warming, with the exception of a shift from forest to agriculture. No clear picture emerged from the impact of planting or seeding new forests.

* Urbanization and conversion to bare soils have the largest warming impacts.

In general, land use conversion often results in more warming than cooling.

The study took an approach called "observation minus reanalysis," or OMR. Through this process, the researchers used temperature data from local ground observations, observation and computer modeling, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and statistical methods. They were able to separate the effects of land use or cover from greenhouse warming and isolate the impact from each land use or cover type. The more detailed data provided a clearer picture of the effects of land surface properties on near-surface temperature trends.

“We showed this quantitatively for the first time,” said University of Maryland atmospheric and oceanic science Professor Eugenia Kalnay, who developed the OMR method with Florida State University Professor Ming Cai. She also is a co-author of the study.

While the effects of greenhouses gases like carbon dioxide are clear, Kalnay said, the study does suggest land use needs to be considered carefully as well.

“I think that greenhouse warming is incredibly important, but land use should not be neglected,” she said. “It contributes to warming, especially in urban and desertic areas.”

Another study co-author, Roger Pielke Sr., said the results indicate that "unless these landscape effects are properly considered, the role of greenhouse warming in increasing surface temperatures will be significantly overstated." Pielke is a senior research scientist in atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Purdue's Gilbert Rochon and Alexander Gluhovsky also participated in the study. Rochon is associate vice president for collaborative research for Information Technology at Purdue (ITaP) and director of ITaP's Purdue Terrestrial Observatory satellite and remote sensing data program. Gluhovsky is a Purdue professor in earth and atmospheric sciences and statistics.

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement program, NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Writer: Greg Kline, 765-494-8167, gkline@purdue.edu

Sources: Souleymane Fall, 765-494-9138, sfall@purdue.edu

Dev Niyogi, 765-494-6574, climate@purdue.edu

ABSTRACT

Impact of land use cover on temperature trends over the continental United States: assessment using the North American Regional Reanalysis

We investigate the sensitivity of surface temperature trends to land use land cover change (LULC) over the conterminous United States (CONUS) using the observation minus reanalysis (OMR) approach. We estimated the OMR trends for the 1979-2003 period from the U.S. Historical Climate Network (USHCN), and the NCEP-NCAR North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR). We used a new mean square differences (MSDs)-based assessment for the comparisons between temperature anomalies from observations and interpolated reanalysis data. Trends of monthly mean temperature anomalies show a strong agreement, especially between adjusted USHCN and NARR (r = 0.9 on average) and demonstrate that NARR captures the climate variability at different time scales. OMR trend results suggest that, unlike findings from studies based on the global reanalysis (NCEP/NCAR reanalysis), NARR often has a larger warming trend than adjusted observations (on average, 0.28 and 0.27 degreesC/decade respectively).

OMR trends were found to be sensitive to land cover types. We analyzed decadal OMR trends as a function of land types using the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) and new National Land Cover Database (NLCD) 1992-2001 Retrofit Land Cover Change. The magnitude of OMR trends obtained from the NLDC is larger than the one derived from the static AVHRR. Moreover, land use conversion often results in more warming than cooling.

Overall, our results confirm the robustness of the OMR method for detecting non-climatic changes at the station level, evaluating the impacts of adjustments performed on raw observations, and most importantly, providing a quantitative estimate of additional warming trends associated with LULC changes at local and regional scales. As most of the warming trends that we identify can be explained on the basis of LULC changes, we suggest that in addition to considering the greenhouse gases-driven radiative forcings, multi-decadal and longer climate models simulations must further include LULC changes.

The article can be accessed at:

https://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122572433/abstract