March 22, 2016

Fungus that threatens chocolate forgoes sexual reproduction for cloning

|

|

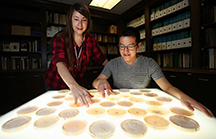

Purdue mycologists Catherine Aime and Jorge Díaz-Valderrama examine cultures of Moniliophthora roreri, the fungus that causes frosty pod rot. (Purdue Agricultural Communication/Tom Campbell) |

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - A fungal disease that poses a serious threat to cacao plants - the source of chocolate - reproduces clonally, Purdue University researchers find.

The fungus Moniliophthora roreri causes frosty pod rot, a disease that has decimated cacao plantations through much of the Americas. Because M. roreri belongs to a group of fungi that produces mushrooms - the fruit of fungal sex - many researchers and cacao breeders believed the fungus reproduced sexually.

But a study by Purdue mycologists Catherine Aime and Jorge Díaz-Valderrama shows that M. roreri generates billions of cocoa pod-destroying spores by cloning, even though it has two mating types - the fungal equivalent of sexes - and seemingly functional mating genes.

The findings could help improve cacao breeding programs and shed light on the fungal mechanisms that produce mushrooms.

"This fungus is phenomenally unusual - it has mating types but doesn't undergo sexual reproduction," said Díaz-Valderrama, doctoral student in mycology. "This knowledge is biologically and economically valuable as we seek better insights into how mushrooms come about and how we can reduce this disease's damage to the cocoa industry."

Cocoa is one of the few major crops produced almost entirely by small farms, and the instability of cocoa prices often makes fungicides a risky investment for growers. Instead, many growers opt to regularly monitor their crop for symptoms of frosty pod rot, burying pods that display the telltale dark lesions or white dusting to prevent further dispersal of fungal spores.

|

|

A healthy pod on a cacao tree at the Garfield Park Conservatory in Indianapolis. (Jorge Díaz-Valderrama) |

Over the last 60 years, the disease has spread - likely through unwitting transportation of infected pods - through much of South America, all of Central America and into Mexico. Frosty pod rot has dropped cocoa yields in some areas by up to 100 percent, forcing many growers to abandon their plantations altogether. Brazil is the only cocoa-producing country in the continental Americas untouched by frosty pod rot, whose pernicious effects have spurred the majority of global cacao production to relocate to West Africa. These regions remain highly vulnerable to the disease, Díaz-Valderrama said.

Understanding the fundamental biology of the fungus could help disease control efforts, but researchers have long been stumped by M. roreri's reproductive habits, which seem to deviate from those of sister species.

Fungal reproduction is complicated. Instead of male and female sexes, fungi can have a vast number of different mating types, leading to a wide and varied range of potential mates - up to 20,000 in some species. But many fungi also reproduce clonally under favorable conditions, simply copying their genome and producing billions of offspring.

Digging into the genomics and population genetics of M. roreri, Aime and Díaz-Valderrama found indications that the fungus might be able to sexually reproduce: It has two seemingly compatible mating types and what appear to be functional sex pheromone receptors. But they couldn't find any evidence that the mating types were recombining in the field or lab, and no records of M. roreri mushrooms exist - signs that the fungus has ditched sexual reproduction in favor of cloning.

"Fungi usually start reproducing via cloning when they're very well suited for their environment," said Aime, associate professor of mycology. "In terms of resources, sex is expensive while cloning is a cheap and easy way to produce a lot of offspring."

The researchers found both mating types in South America and only one type in Central America. This supports the hypothesis that the disease originated in South America and was more recently introduced into Central America where it rapidly spread through clonal reproduction.

The study also shows that what some researchers believed to be different varieties of the fungus are actually genetic variations in the two mating types. The findings open the door for breeding programs to investigate which mating type is more virulent and possibly develop resistant cacao cultivars.

In the meantime, chocolate lovers should stay calm, Díaz-Valderrama said.

"We're working on identifying biochemical components that could be useful for controlling frosty pod rot and protecting vulnerable cacao-growing regions."

The study was published in Heredity and is available to journal subscribers and on-campus readers at http://www.nature.com/hdy/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/hdy20165a.html.

The research was funded by the Purdue Department of Botany and Plant Pathology.

Writer: Natalie van Hoose, 765-496-2050, nvanhoos@purdue.edu

Sources: Jorge Díaz-Valderrama, 765-494-7791, jdiazval@purdue.edu

M. Catherine Aime, 765-496-7853, maime@purdue.edu

ABSTRACT

The cacao pathogen Moniliophthora roreri (Marasmiaceae) possesses biallelic A and B mating loci but reproduces clonally

J.R. Díaz-Valderrama 1; M.C. Aime 1

1 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA

E-mail: jdiazval@purdue.edu

The cacao pathogen Moniliophthora roreri belongs to the mushroom-forming family Marasmiaceae, but it has never been observed to produce a fruiting body, which calls to question its capacity for sexual reproduction. In this study, we identified potential A (HD1 and HD2) and B (pheromone precursors and pheromone receptors) mating genes in M. roreri. A PCR-based method was subsequently devised to determine the mating type for a set of 47 isolates from across the geographic range of the fungus. We developed and generated an 11-marker microsatellite set and conducted association and linkage disequilibrium (standardized index of association IAS) analyses. We also performed an ancestral reconstruction analysis to show that the ancestor of M. roreri is predicted to be heterothallic and tetrapolar, which together with sliding window analyses support that the A and B mating loci are likely unlinked and follow a tetrapolar organization within the genome. The A locus is composed of a pair of HD1 and HD2 genes, whereas the B locus consists of a paired pheromone precursor, Mr_Ph4, and receptor, STE3_Mr4. Two A and B alleles but only two mating types were identified. Association analyses divided isolates into two well-defined genetically distinct groups that correlate with their mating type: IAS values show high linkage disequilibrium as is expected in clonal reproduction. Interestingly, both mating types were found in South American isolates but only one mating type was found in Central American isolates, supporting a prior hypothesis of clonal dissemination throughout Central America after a single or very few introductions of the fungus from South America.

Agricultural Communications: (765) 494-2722;

Keith Robinson, robins89@purdue.edu

Agriculture News Page