Superconductor 'flaws' could be key to its abilities

August 22, 2012

|

|

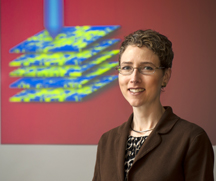

Purdue physicist Erica Carlson stands in front of an illustration of the fractal clusters present in copper-oxygen based superconducting material. (Purdue University photo/Mark Simons) |

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Many researchers studying superconductivity strive to create a clean, pure, perfect sample, but a team of physicists found that some flaws might hold the key to a material's unique abilities.

Erica Carlson, a Purdue University associate professor of physics, led a team that mapped seemingly random, four-atom-wide dark lines of electrons seen on the surface of copper-oxygen based superconducting crystals. The team uncovered a pattern in these flawed lines, which are separate from the expected structure of the material, and discovered that they exist throughout the crystal. The findings suggest the lines could play a role in the material's superconductivity at much higher temperatures than others.

"This material is ceramic, like your dinner plates, and it has no business conducting electricity, but under the right conditions it conducts electricity perfectly with zero energy loss," Carlson said. "A better understanding of how and why this superconductor works could help us design better ones. If we can create a superconductor that works at high enough temperatures, it could transform how we use and generate energy."

For instance, room temperature superconductive wires could lead to power lines that do not leak electricity in transit, saving tremendous amounts of energy and money. Superconductors also have special magnetic properties that could allow for levitated, frictionless trains and stronger, more durable permanent magnets like those used in wind turbines, she said.

The electrons confined to these mysterious lines behave radically different than those that freely move throughout the crystal, and it had been suggested that they could play a role in superconductivity. However, whether the lines were merely surface effects or extended into the material was unknown because the scanning tunneling microscopy that reveals them can only be used on the material's surface, she said.

Carlson collaborated with Karin Dahmen from the University of Illinois and Purdue graduate student Benjamin Phillabaum on a study to examine the tiny, ladderlike lines that point vertically or horizontally across the surface of the crystal. By treating sets of neighboring parallel lines as part of a single "cluster," the team discovered that the patterns formed by the clusters are fractal in nature, meaning they fall between two dimensions of space, Carlson said.

"When thinking of a fractal, imagine a crumpled piece of paper," she said. "It is more than the two-dimensional flat piece of paper and it enters three dimensions, but it does not quite fill that space. It is not a true and solid ball. Fractals can occupy fractions of a dimension. They also have a pattern that is maintained even as you view smaller and smaller pieces of it."

Fractal patterns are mathematically understood, and the patterns present on the surface of the copper-oxygen based high-temperature superconductors could be compared to known models of how that pattern can arise. Using this information, the team was able to determine that these patterns originate from deep inside the material. A paper detailing the NSF and Research Corporation for Science Advancement-funded research was published in Nature Communications.

The fractal patterns also offer information about the space they occupy, and through this work the team developed a new analysis method to help understand the materials and the interactions going on inside of them, Carlson said.

"If you see pattern formation, then you can try to identify the fundamental physics causing its formation," she said. "It can apply to a lot of systems and materials beyond superconductors."

Carlson said the method could be used to identify the dominant class of disorder present in a material, which helps in understanding its unique characteristics.

"We want to move beyond trying to get rid of disorder, striving for unattainable purity in the materials we examine, and instead take the disorder into account and use it to our advantage," Carlson said. "These little patches of imperfection where things aren't lined up in a perfect crystal lattice are important, and old methods that overlooked them fail to capture important physics. The flaws in the lines are like a fingerprint. They reveal the identity deeper inside."

The team next plans to look at pattern formation in other superconductive materials.

Writer: Elizabeth K. Gardner, 765-494-2081, ekgardner@purdue.edu

Source: Erica Carlson, 765-494-3041, ewcarlson@purdue.edu

Related website:

Carlson research group

ABSTRACT

Spatial Complexity Due to Bulk Electronic Nematicity in a Superconducting Underdoped Cuprate

B. Phillabaum, E.W. Carlson and K.A. Dahmen

Surface probes such as scanning tunneling microscopy have detected complex electronic patterns at the nanoscale in many high-temperature superconductors. In cuprates, the pattern formation is associated with the pseudogap phase, a precursor to the high-temperature superconducting state. Rotational symmetry breaking of the host crystal in the form of electronic nematicity has recently been proposed as a unifying theme of the pseudogap phase. However, the fundamental physics governing the nanoscale pattern formation has not yet been identified. Here we introduce a new set of methods for analyzing strongly correlated electronic systems, including the effects of both disorder and broken symmetry. We use universal cluster properties extracted from scanning tunneling microscopy studies of cuprate superconductors to identify the fundamental physics controlling the complex pattern formation. Because of a delicate balance between disorder, interactions and material anisotropy, we find that the electron nematic is fractal in nature, and that it extends throughout the bulk of the material.