Reporting from the stars

For the answers to the universal questions, Dan Milisavljevic looks to the sky. Quite literally.

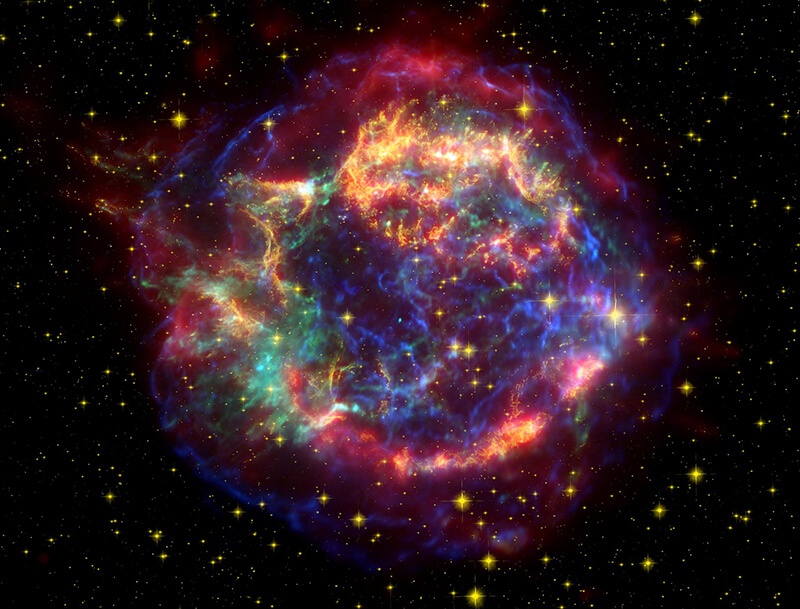

Milisavljevic (pronounced mili-sahv-le-vich), an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University, is one of very few scientists who studies both massive star explosions called supernovae and their debris fields called supernova remnants. These explosions and their remnants often produce space’s most dazzling and colorful images.

Milisavljevic has emerged as an expert on the turbulent events that occur within the dynamic universe and is a leading researcher of how astronomical objects change over time. This burgeoning field of study is called time-domain astronomy.

The concept of a dynamic universe and time-domain astronomy are both 20th-century creations that have been transformed by 21st-century innovations.

The dynamic universe concept views the universe as a volatile system punctuated by violent events — including the explosion of stars, or supernovae. The concept replaced the centuries-old view of the universe as a region of relative tranquility and sparked the growth of time-domain astronomy, which depends on the marriage of multimessenger astronomy — the study of “messenger” signals from extrasolar events — with sophisticated Big Data management.

In order for scientists to analyze as many signals as possible, Milisavljevic is helping create a system that would place the universe under constant, connected surveillance from locations all around the globe. Whether it’s a professional astrophysicist at a cutting-edge observatory in Chile or a farmer and amateur astronomer in New Zealand, astronomers everywhere can observe phenomena and catalog them in a centralized online location in real time, around the clock, every day.

“I consider myself to be a reporter on the universe,” said Milisavljevic, who specializes in understanding supernova explosions. “Sometimes, I’m the first human to have seen something happen trillions of billions of miles away, and there is a real thrill in being able to see that, characterize it and understand what’s going on.

“This is a great time for astronomers, and technology absolutely plays a critical role in that. There’s a lot going on out there — a supernova goes off somewhere in the universe every second — and there is an incredible amount of sky to cover. New technologies have increased our capacity to find things to study, coordinate our efforts and process all the information.”

Backyard explosions

Milisavljevic’s research can generally be divided into two categories: the near-forensic study of supernova remnants in our own Milky Way galaxy, which can now be enhanced by virtual-reality reconstructions; and investigations of supernovae and other “transient” events that take place in the wider universe. The study of these many transients, which are disruptive events that exist for limited periods of time, have been made possible by advances in observational, communications and machine-learning technology.

Milisavljevic has recently done groundbreaking research on two supernova phenomena — Cassiopeia A and SN 2012au.

Milisavljevic co-authored a 2015 report that presented near-infrared observations of Cassiopeia A, a supernova remnant in the Milky Way, and a three-dimensional map of its interior unshocked ejecta. The investigation provided new information on the potential explosive properties, mass loss and long-term fate of core-collapse supernovae.

Then, in 2018, Milisavljevic co-authored a report announcing unique observations of SN 2012au, a distant supernova that exploded in 2012. Unlike most transient events, whose duration normally lasts no more than a few months, SN 2012au was still luminous six years later. Milisavljevic and his team believe this is because the supernova produced a rare pulsar wind nebula, a strongly magnetized and rapidly rotating neutron star that continues to power the supernova.

“A large component of my research is dedicated to looking at those explosions that happened in our own backyard, in our own galaxy. They are resolved — you can actually see where the stellar debris has gone and its characteristics,” said Milisavljevic, who likens supernova reconstruction to a bomb-squad investigation.

“Galactic supernovae like Cassiopeia A are rare but nearby and resolvable. Extragalactic supernovae are numerous but far away and almost always impossible to resolve,” he said. “These events are very diverse, so I need to find out how this particular star exploded and what type of star it was before it exploded. It’s very exciting, and it helps us understand the possible characteristics of unresolved phenomena that are farther away.”

Transformative innovations

At Purdue, Milisavljevic has enhanced his ability to study remnant characteristics by using the cutting-edge VR technology of Purdue’s Envision Center to produce enriched, interactive reconstructions. Previously, he had been limited to building reconstructions of supernovae phenomena on a computer screen.

“What we’re doing here is something that could really transform how we explore complex datasets,” Milisavljevic said.

Technological advances are also part of another Milisavljevic project: The Recommender Engine for Intelligent Transient Tracking (REFITT) network, that could revolutionize the observation capabilities of researchers around the world.

REFITT will be a global, artificial intelligence-directed telescope network that leverages interdisciplinary expertise in research computing, statistics and computer science. The network, strategically centered at Purdue, optimizes advances in both hardware and software to connect academic researchers with amateur astronomers, centralize efforts, process information and analyze results.

“You could say that the goal of REFITT is to crowdsource Earth to watch the universe,” Milisavljevic said. “Technology developed in the last five years has made it much easier for astronomers, including amateurs, to make important contributions. In the not-too-distant future, there will be tens of thousands of transients to potentially follow on any given night. That’s great, but it has also opened up a huge fire hydrant of data — and observatories are already struggling to follow up on these discoveries.

“We’re positioning Purdue to be a central hub that sorts through and simplifies this data, with the goal of making tailored recommendations for people with access to telescopes to make optimal observations. I really do think that is pioneering.”

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a top public research institution developing practical solutions to today’s toughest challenges. Ranked the No. 6 Most Innovative University in the United States by U.S. News & World Report, Purdue delivers world-changing research and out-of-this-world discovery. Committed to hands-on and online, real-world learning, Purdue offers a transformative education to all. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue has frozen tuition and most fees at 2012-13 levels, enabling more students than ever to graduate debt-free. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap at https://purdue.edu/.

Writer: Aaron Martin

Purdue News Service contact: Amy Patterson Neubert, 765-412-0864, apatterson@purdue.edu

Source: Dan Milisavljevic, dmilisav@purdue.edu