‘Mr. Science’: Health Sciences alum made noise at Purdue, now makes it for his students

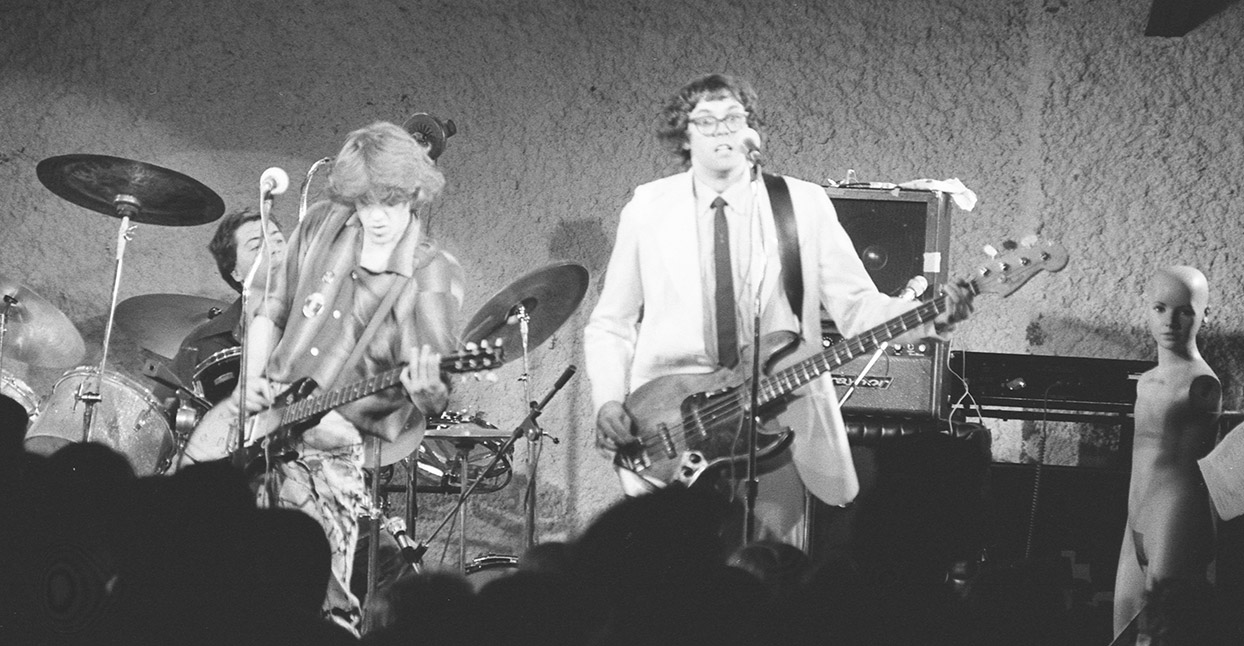

Brad Garton, right, then also known as Mr. Science, plays bass guitar next to his Dow Jones and the Industrials bandmates drummer Tim North, left, and guitarist Greg Horn, middle, 40 years ago.

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Thanks to the power of Google, at least a few of Brad Garton’s students ask him the same question every year.

“Uh, were you Mr. Science?”

Brad Garton today.Photo provided

Garton, a 1979 Purdue University School of Health Sciences alumnus who is now director of the Computer Music Center at Columbia University, was once known by that moniker when he was an undergraduate student conducting research and performing in front of thousands of his fellow Boilermakers as part of the punk rock band Dow Jones and the Industrials. He often wore a lab coat while playing synthesizers and sometimes bass guitar as he sang songs like “Mental Disease” and “Latent Psychosis.”

Forty years ago, Dow Jones was a West Lafayette sensation, packing the Purdue Armory as well as playing shows in Indianapolis and Bloomington. Bassist Chris Clark was elected Purdue Student Government president under such campaign “promises” as changing Purdue’s school colors to fluorescent green and pink, randomized dorm-mates every semester, and to somehow turn Mackey Arena into the world’s largest bowl of corn flakes. Garton’s first shows with the band were in front of hundreds of fans embracing punk, new wave and other strange sounds, which seemed to hit Indiana with (anti)authority in the late 1970s and early ‘80s.

“Let’s be honest: We were in the middle of northern Indiana. It wasn’t the cultural Mecca that some places might be. In order to do the kind of music that we enjoyed, we had to do it ourselves,” said Garton from his New York home. “That’s that work ethic. That made me very proactive about creating and building and doing.”

Balancing rigorous academics with a band that would become one of the pillars in Indiana punk rock history was a challenge at times. Garton was also embracing his interest in audio recording techniques and an odd new thing called digital music.

Experimenting in music, majors and labs

Garton began as a first-year electrical engineering student before switching to biology and then pharmacology studies. After realizing his passion for research, he finished out his undergraduate work in health sciences. He finally found his academic fit by joining research projects that relate to the human response to music and sound.

“I was really interested in how the brain works and basically how you perceive music,” Garton recalled. “I didn’t want to do the externship that pharmacology required. I really wanted to do research.”

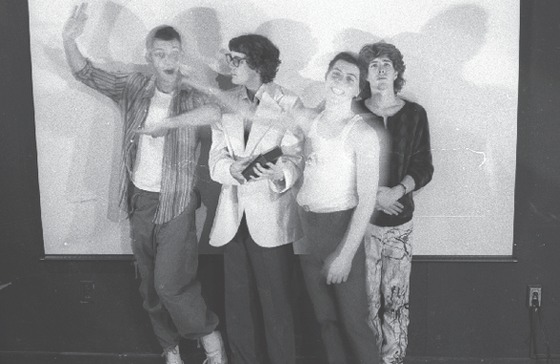

Dow Jones and the Industrials rocked Purdue University from 1979-1981. They were, from left, Chris Clark, Brad “Mr. Science” Garton, Tim North and Greg Horn.Family Vineyard Records

One project looked at how metal ions cross brain cell walls to discharge neurons. Garton also conducted graduate research in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, investigating low-level perceptual mechanisms of the ear.

While teaching students the ins and outs of digital music and audio creation is his main focus today, he is still interested in studying music’s effects on the brain.

“Stuff I’ve learned at Purdue has come back to reinform some of that. We do a lot of work with what we call data sonification,” Garton explained. “We’re working with a Columbia neuroscientist, looking at how we can attach audio to specific molecular reactions that are happening. We can sonify that and turn it into music.”

Then there are graduate students like Nicola Hein that turn up the brain and music relationship to 11.

“He’s building guitar pedals that rely upon neuronal tissue cultures to make particular decisions about how the sound is processed,” said Garton of his student with amazement. “So, we have a stomp box with neurons in it.”

Computer music

After Garton’s years at Purdue, the Columbus, Indiana, native took a gamble that led him to the Garden State. He applied at Princeton University’s then-fledgling computer and digital music program, which was difficult to get into just like the Ivy League school’s more time-honored curricula. He earned his PhD in 1989 before joining the faculty at nearby Columbia, just 61 miles up I-95 from New Jersey.

Garton credited his years at Purdue — and his future wife, Jill Lipoti — for supplying him the confidence to study this then-new form of music developed by machines and programs instead of guitars and drums. From his general education requirements of calculus and computer programming to his research in programs that would become College of Health and Human Sciences departments, Garton said he wouldn’t have been able to succeed at Princeton without his Purdue foundation.

“At the time, I had been working a lot in studios, and I heard about this new stuff called digital audio. Believe me, jumping into learning about digital audio in 1982 was one of the better decisions I ever made,” Garton added. “We were working on a big mainframe with 2K of RAM or something. Very powerful (laughs). It was really quite an exciting time, and then I just rode the wave of technology.”

Those same students that are discovering Mr. Science and Dow Jones and the Industrials are already more adept at digital music than Garton was as a PhD student in the ‘80s, he said. Like in his research days in Purdue Health Sciences, the work is ever-evolving, and with digital music heavily represented in almost every top-40 song, movie and streaming show, Garton’s gamble to pursue music has more than paid off.

“Let me put it this way: I’m glad I’m old now, and I don’t have to compete with my students because they are just over the top, man. It’s just amazing,” Garton said. “I just pinch myself every morning because of the people I work with and the students I have. We do attract some of the best students in the world, and they do incredible projects.”

And his students are still mostly impressed with Mr. Science, even though they were born decades after he last made noise in West Lafayette.

“Oh, I think they think it’s kind of charming,” Garton said. “A lot of them are in bands now. It’s a way of connecting to a previous self. ‘Yeah, I was kind of like you at one point.’”

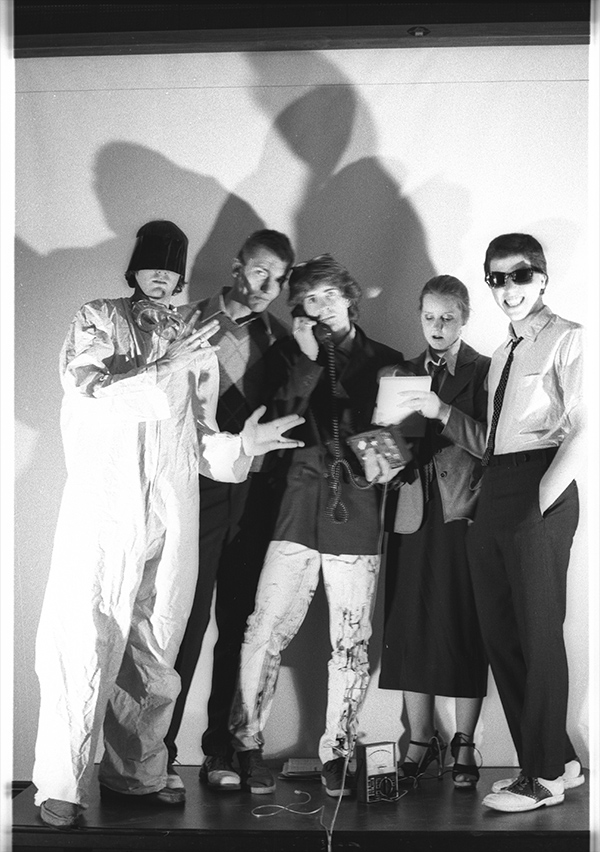

Brad “Mr. Science” Garton, left, and the band were sometimes joined on-stage by their administrative assistant, “Ms. Johnson,” second from the right.Keith Smith