Challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder increased significantly for households facing income and food insecurity during COVID-19 pandemic

By Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Routine and structure are often essential in the lives of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, those key elements were upended in most parts of their lives. From schools shifting online to the temporary unavailability of favorite foods, many families experienced significant challenges.

Anita Panjwani, postdoctoral research fellow

A Purdue University study surveyed hundreds of families across the U.S. that have children with ASD to see how the pandemic affected behaviors at home, especially when food insecurity was a concern. Authored by Anita Panjwani, postdoctoral research fellow in the Purdue Autism Research Center and the Department of Nutrition Science; Bridgette Kelleher, associate professor of psychological sciences; and Regan Bailey, professor of nutrition science, the study was recently published in Research in Developmental Disabilities.

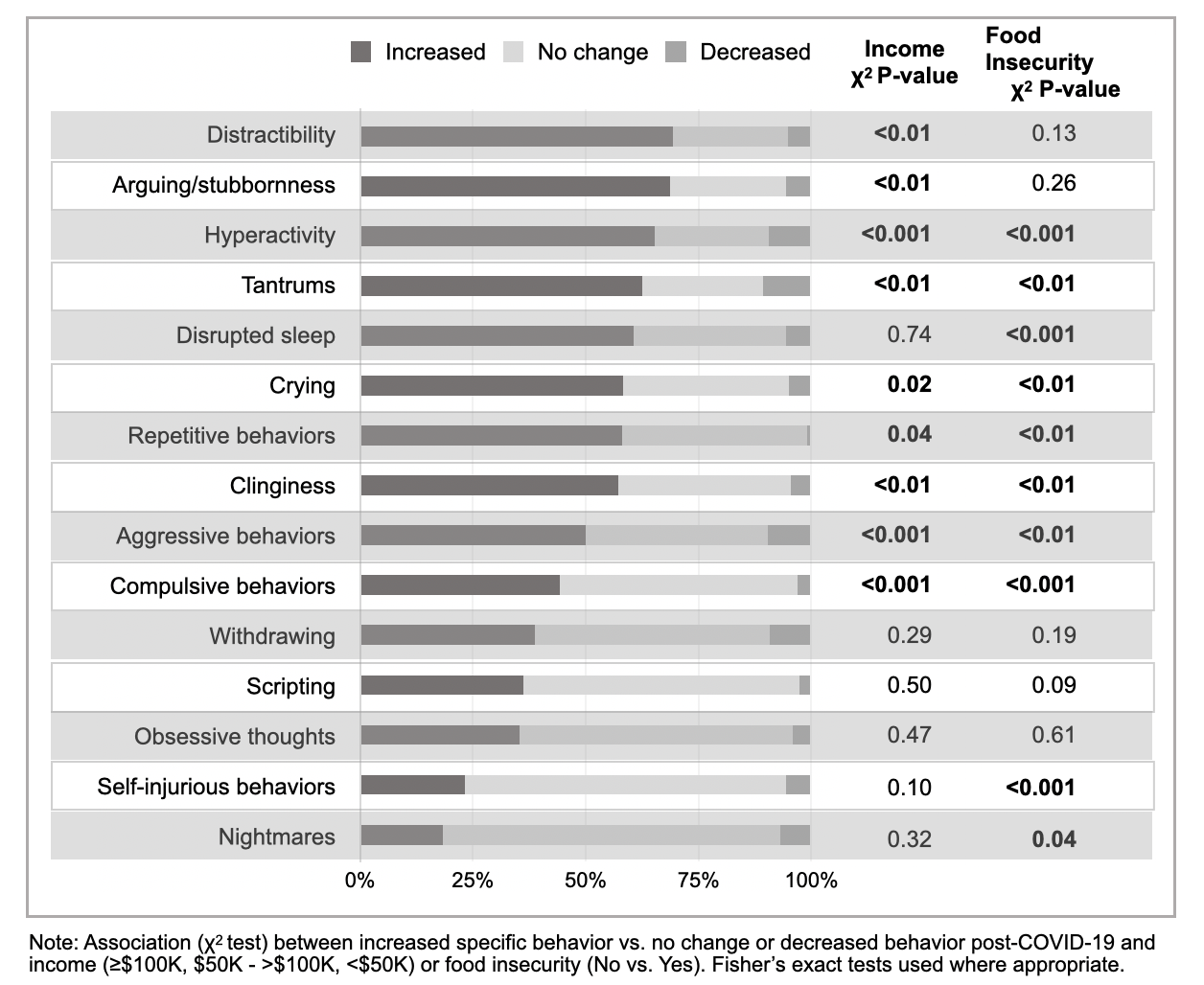

Recruited through social media in May and June 2020, one caretaker or parent from 200 households completed online surveys pertaining to increasing, decreasing or steadiness of 15 behavioral traits commonly found in children with ASD — hyperactivity, tantrums and clinginess, for example. Demographics were measured, too, with major focus on household income. Panjwani divided pre-pandemic household incomes into three groups: less than $50,000, $50,000 to less than $100,000, and $100,000 or greater.

Using the Unites States Department of Agriculture’s definition of food insecurity as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food,” Panjwani found many households were affected post-pandemic by lack of access to foods usually in their diets, which in turn affected their children with ASD.

“There were a lot of struggles. A lot of these families depended on schools, churches, food banks and food pantries, neighbors, and other families for support,” said Panjwani, who brought statistical analysis expertise along with her nutrition research experience to the College of Health and Human Sciences. “Not only do children and individuals with ASD have more regimented lifestyles and meal structures, but they’re also inclined to have higher sensitivities to taste, texture and smells. That goes hand in hand with what kinds of foods they choose to eat. That’s even harder, presumably, for them during the pandemic.”

A majority of respondents reported a moderate-to-large influence on the child’s overall behavior (74%) during the pandemic. However, behaviors such as aggression and compulsiveness were more prevalent in households experiencing food insecurity. Overall, 10 of the 15 specific behaviors, including aggression, hyperactivity, and sleep problems, significantly increased in the food-insecure households compared to food-secure households, according to survey results.

This table developed by post-doctoral fellow Anita Panjwani shows the increase levels of 15 behaviors associated with autism spectrum disorder found in 200 U.S. children in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The right columns separate low income and food insecure families. The bolded numbers represent behaviors that saw significant increase a year ago.

“Food insecurity was still significant,” said Panjwani, whose work was funded by Purdue’s Discovery Park Big Idea Challenge Grant and the National Institute of Mental Health. “Even after accounting for other sociodemographic factors, including sex, age and race of the child as well as shelter regulations, loss of employment and food assistance.”

Additionally, Panjwani found more families with lower incomes before the pandemic experienced job loss or pay reduction during those first few months of COVID-19, perpetuating existing disparities. Such household disruption could present negative effects to the children in the study, who ranged from age 2 to 17.

Questions on caregiver stress, eating habits and nutrition were asked for later publication.

Panjwani said data from this study may be useful to tailor public health policy and interventions to mitigate the effects of the pandemic among vulnerable population subgroups within the autism community. It could also better prepare families for if and when another pandemic disrupts daily life.

“We hope to compile a best-practices list that can be shared with the wider autism community and others with different needs,” Panjwani said.