Holy guacamole! Purdue Health Sciences researcher’s new study finds traces of toxic metals in avocados

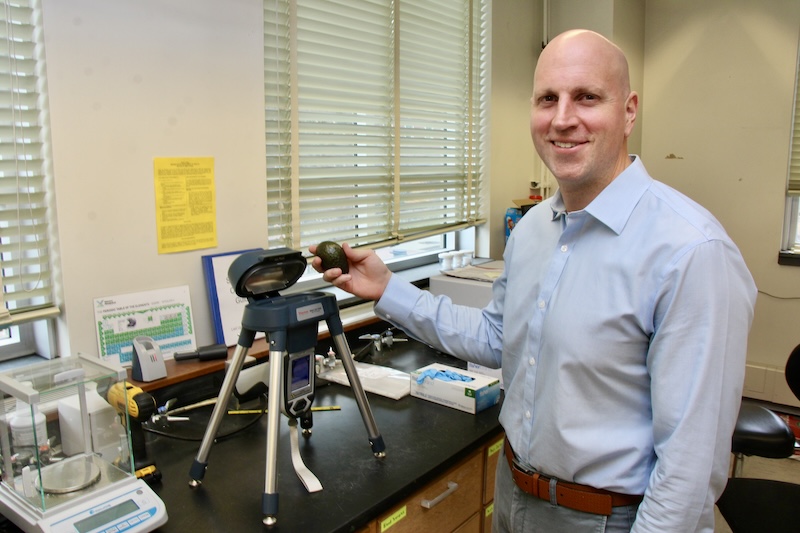

A recent study by Aaron Specht, assistant professor in the Purdue University School of Health Sciences, found traces of toxic metal elements on avocados from Mexico and California. Specht used portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) on 24 avocados, which found elements like mercury on some of the fruit. (Tim Brouk)

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

More than 3 billion pounds of avocados were imported from Mexico to the United States in 2024, according to The Wall Street Journal.

That’s a lot of guacamole for your Purdue University basketball watch parties. It can also be a lot of toxic elements hitchhiking into your system with every dip of the chip.

A recent international study from Aaron Specht, assistant professor in the Purdue School of Health Sciences, and his team of researchers analyzing avocados from Mexico and California for toxic elements — metals like lead, manganese and mercury that can be harmful to humans if consumed in large amounts. The team used two measurement processes on the fruit — inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF). While revealing what elements could be found on the avocados, the scientists wanted to see if pXRF, which can be carried in a small suitcase into the field, would perform compared to larger, lab-based ICP-MS technology.

Both methods scanned 24 commercially sourced, organic and standard Hass avocados — 12 from Mexico and 12 from California — and both found traces of mercury, manganese, cobalt and iron. These elements are not naturally found in Hass avocados, a popular avocado variety originating from California and known for its dark green and bumpy skin.

“This would be a man-made problem, very much so. A lot of the time when you’re using pesticides on farms, they’re containing a lot of these (toxic metals),” said Specht, who led the pXRF portion of the study. “And maybe it’s not pesticides that were used today or this year. It was pesticides that were used in the past, or it’s from industrial processes that happened in the past, or it’s from our use of leaded gasoline. It can come from a variety of sources.”

The findings and the methodology could inform farmers of toxic elements in their soil and pesticides, and with pXRFs scans taking usually just a couple minutes, the farmers could get real-time data on what is on and in their produce.

This research is a part of Purdue’s presidential One Health initiative that involves research at the intersection of human, animal and plant health and well-being.

An avocado is placed in a stand on top of a pXRF scanner in Specht’s lab.(Tim Brouk)

Methodology

While Specht has traveled thousands of miles with his pXRF kit, this work was done in his Purdue lab. Most of the avocados were placed in a pXRF stand. The pXRF gun was fastened into the stand and found readings in minutes. For avocados too large for the stand, he placed the pXRF gun onto the fruit’s mesocarp, the green middle of the avocado, and the exocarp or skin of the avocado. Like his previous work with humans and large birds, the pXRF gun gave Specht accurate measurements when placed against the fruit.

The highest concentrations of toxic metals were found on the exocarp, but there were still elements inside that tough skin. Most of the avocados had traces of mercury inside the fruit. While low in absolute terms, the amount exceeded conservative produce reference thresholds, prompting the researchers to call for further mercury speciation research.

“For some of these toxic metals, it’s possible the effect would be minimal on a given person,” Specht said. “We do know most of them that we were measuring and particularly looking at don’t have a known good impact in the body. They’re only going to do detrimental things in the body. So, any amount is typically thought to be harmful.”

Implications

While the ICP-MS method of ablating the fruit into small particles via a plasma torch then measuring the element mass to charge ratio found more elements than the pXRF method, a single ICP-MS scan can take about one week to complete when compared to pXRF’s usual two- or three-minute range. Farmers may not want to wait a week to see if their avocado farm is using tainted soil or dangerous pesticides. Getting such fast analysis to the avocado fields is a huge advantage for Specht’s pXRF methods.

“You could do real-time measurements in the field to identify if there are problems in the food that you’re producing,” Specht explained. “In this case, we could easily tell if there was a problem going on based off of the profiles that we were seeing.”

For American consumers — who eat an average of nine pounds of avocados a year, according to the United States Department of Agriculture — such analysis before the avocados arrive to the produce section of their grocery store will give them ease of mind when they take their next chip dip into that zesty guac.

“This is beneficial to farmers and consumers if we can try to minimize and figure out the sources for some of these (toxic metals),” Specht said. “Going into the farms and being able to do these measurements is of interest to us and to try to figure out, ‘OK, well, what’s working and what’s not for getting avocados the healthiest they can possibly be?’”

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.