Purdue Nutrition Science researchers identify novel connection between fat accumulation and breast cancer metastasis

Written By: Rebecca Hoffa, rhoffa@purdue.edu

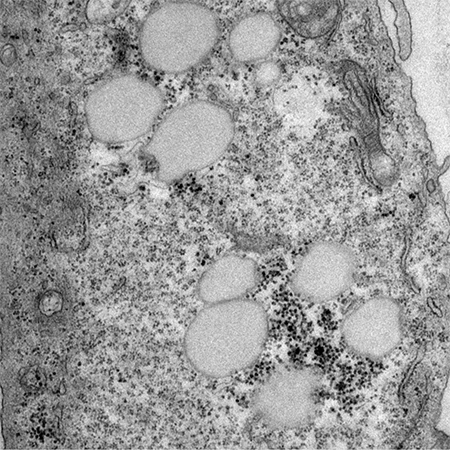

The researchers looked at how non-metastatic versus metastatic cells would take up and synthesize fatty acids in the cell, as well as how much of that fatty acid is stored and how much they oxidize or burn, to determine how these processes are different in metastatic cells.(Photo provided by the Teegarden Lab)

When breast cancer metastasizes, or spreads, to other organs in the body, five-year survival rates dip to 32%, compared to more than 99% when the cancer is diagnosed before it has spread, according to the American Cancer Society. This grave statistic drives researchers like Purdue University Department of Nutrition Science postdoctoral scholar Chaylen Andolino and professor Dorothy Teegarden to look for treatments to improve breast cancer outcomes.

Andolino and Teegarden recently published their study “Fatty Acid Synthase-Derived Lipid Stores Support Breast Cancer Metastasis” in Cancer & Metabolism. The work, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, examined how breast cancer cells use fat to metastasize compared to cells that do not metastasize.

Dorothy Teegarden

“The association between fat accumulation, cancer aggressiveness and poor patient outcomes has been identified for decades in breast and other cancers,” Andolino said. “But how those fats accumulate and what those fats do, especially in promoting cancer to metastatic progression, is still not understood.”

The team of researchers, including collaborators professor Michael Wendt from the University of Iowa and professor Stephen Hursting from the University of North Carolina as well as professor Kimberly Buhman from Purdue’s Department of Nutrition Science, noted the work shows potential for new treatment targets, including dietary interventions.

In order to successfully metastasize, cancer cells undergo various steps and need to adapt to utilize different compounds, such as glucose or fatty acids, for energy to complete these processes.

“There are very few cells that actually make it,” Teegarden explained. “Only a few cells, even single cells, successfully migrate and survive to ultimately colonize and grow into a new lesion in other areas of the body.”

The researchers looked at how the non-metastatic versus metastatic cells would take up and synthesize fatty acids in the cell, as well as how much of that fatty acid is stored and how much they oxidize or burn, to determine how these processes are different in metastatic cells.

Chaylen Andolino

“We focused especially on steps that are required for metastasis to happen, such as migration — the ability of cells to move out of the primary site, which is a critical step in metastasis,” Andolino said. “We also studied how the metastatic cells utilize energy from fat when they are detached from their basement membrane, a step that normal cells don’t survive.”

The results of the study showed metastatic breast cancer cells store and use fats for energy in an abnormal way, ultimately using them to enhance survival to invade other parts of the body.

“The way these metastatic cancer cells manage the fats is really quite different,” Teegarden said. “They make their fats, store them and release them from those stores as needed, but these steps happen at the same time, which is not normal. Because of these altered processes, the metastatic cells develop large fat droplets, and this storage allows their use to aid in adapting to the many steps during metastasis, unlike non-metastatic cells.”

These metastatic cancer cells increase the amount of fat they make, store more of that fat, and then utilize it for energy, which makes them able to adapt to all the harsh conditions they must survive in order to metastasize.

“Metastasis is the number one killer for all cancer patients,” Teegarden said. “More than 90% of cancer mortality is due to metastasis. In theory, if we could characterize how a primary tumor utilizes fat, we may be able to develop specific treatments that would inhibit metastasis.”

Metastatic cancer cells develop and store large lipid droplets (pictured).(Photo provided by the Teegarden Lab)

Ultimately, Andolino and Teegarden are looking to mitigate metastasis potentially through dietary interventions. Teegarden has previously published work looking at vitamin D’s role in breast cancer prevention, so the research team is hoping to investigate further how the vitamin can influence this process to reduce metastasis. In particular, they have shown that the active form of vitamin D reduces the level of the enzyme pyruvate carboxylase, which is involved in supporting enhanced fatty acid synthesis in breast cancer cells. According to a previous publication from the lab, when that enzyme level is reduced in cancer cells, it reduces lung metastasis by 80%, potentially through its effects on fatty acid metabolism.

“The hope is that bridging the knowledge of vitamin D’s role in breast cancer metabolism with the work completed in the current study will help identify safe dietary interventions that may contribute to preventing breast cancer progression to metastatic disease by limiting fatty acid availability in the cells to adapt to the harsh environments encountered during metastasis,” Teegarden said.

This research is a part of Purdue’s presidential One Health initiative that involves research at the intersection of human, animal, and plant health and well-being.

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.