Purdue researchers help bridge brain tumor cesium-131 radiotherapy from humans to canines

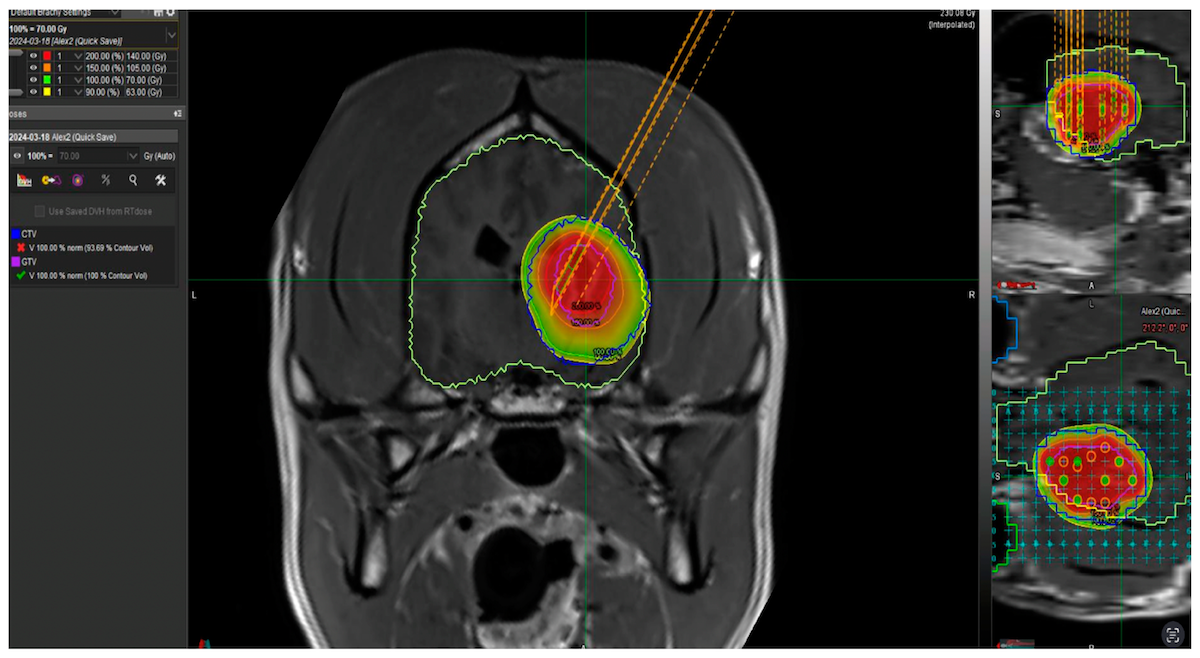

This MRI scan of a dog’s brain shows where the cesium-131 “seeds” will be placed for brachytherapy. The dog had a brain tumor removed and the cesium-131 will serve as an inner radiotherapy to deter tumor regrowth.(Image provided)

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

The use of cesium-131 “seeds” to combat the reemergence of cancerous tumors has been used in humans for more than 20 years, but a team consisting of current and former Purdue University researchers has modified the form of radiotherapy to also be successful in dogs, according to a recently published study in Radiation.

Matt Scarpelli, assistant professor in the Purdue School of Health Sciences; Joshuah B. Klutzke, neurosurgery resident in the Purdue Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences; former Purdue Veterinary Medicine faculty members led by Isabelle F. Vanhaezebrouck and Tim Bentley; and others comprised an international all-star team of scientists that orchestrated a successful surgery and recovery of a 10-year-old male Australian shepherd that had brain tumors removed. This research is a part of Purdue’s presidential One Health initiative that involves research at the intersection of human, animal and plant health and well-being.

The dog had 20 cesium-131 seeds implanted into its brain. Representing a form of radiotherapy called brachytherapy where radioactive materials are placed inside or near a tumor, the seeds are radioactive isotopes and act like internal radiation therapy. While cesium-131 is radioactive and requires safety requirements, such as lead aprons when in use, its half-life is short (less than 10 days), and its 30.4 kiloelectron volts photon emission is considered low. Its radiation disappears totally after 97 days. The authors stated, “Due to its fast decay and low energy activity, cesium-131 is considered a safe treatment choice compared to other radionuclides.”

Matt Scarpelli stands in his lab inside the Hansen Life Sciences Research Building.(Tim Brouk)

The dog was monitored for six months after the 2024 surgery at the Purdue University Veterinary Hospital. Immediate recovery required anti-seizure and anti-inflammatory steroid medications, but these were reduced after about six weeks when the dog began walking regularly. The dog was running in the park 10 weeks after surgery and enjoying life again.

“This is the first time it’s ever been done,” Scarpelli said. “The last follow-up six months later was tumor-free. That’s a long time. Whether it’s a human or a dog, six months without a brain tumor in a recurrent case is a long time.”

This new brachytherapy method could be a new alternative to extending the life of man’s best friend.

Planting seeds

Before the dog went under surgery, an MRI scan of the dog’s brain was conducted. MRI is the “gold standard” in detecting and monitoring brain tumors because they show up better on MRI than X-ray or CT (computed tomography) scans.

After imaging revealed the location of a tumor, it was removed, and the cesium-131 were arranged in two parallel rows inside the dog’s brain near the area where the tumor was. Scarpelli said it’s common practice in human patients to use cesium-131 in an area after a tumor is surgically removed.

“They’ll just put the seeds right in there to get any residual tumor that was missed,” Scarpelli explained. “And the same thing in the dog.”

In humans and dogs, using radiotherapy on brain tumors usually involves external beams fed into the targeted area, which requires a linear accelerator. However, the researchers for this dog surgery mainly relied on those 20 implanted seeds due to the canine’s much smaller size to an adult human. Eliminating the need for expensive linear accelerator machines adds to the benefits of the cesium-131 treatment.

“With external beam radiation, the tumor always recurs, and that’s where they get more creative,” Scarpelli said. “That’s when they’ll do another surgery to take out the recurrence, and then they’ll do more experimental things like brachytherapy. … Usually, their survival is not very good, and you’re extending life by a few months.”

But for dogs, brachytherapy, including cesium-131, could have better results — the smaller the animal, the smaller the tumor and the smaller the cancerous area of brain tissue.

“In the veterinary case, you don’t need to have this big fancy equipment to generate the radiation beam. You just need to order the seeds,” Scarpelli said. “So, in a veterinary space, it’s a little more accessible, we think.”

Humans too

The work in the study could inform human brain tumor treatments. While an approved form of brachytherapy since 2003, the cesium-131 seeds combined with external beam radiotherapy could be a more prominent method in the removal of cancerous brain tumors because “canine patients could serve as preclinical models for research on combination therapy,” the paper read.

Scarpelli added, “Having veterinary collaborators is really important to moving whatever you’re developing in the lab into humans. It’s a great segue to humans, and it provides a stepping stone to test something that is experimental, but going into dogs is a little bit easier.”

With only external beam radiotherapy, he explained, a patient usually has a few-weeks gap between tumor removal surgery and the beginning of external beam radiation therapy. In that time, a tumor has a chance to regrow. In brachytherapy, a tumor could be removed, and cesium-131 could be implanted right after the tumor removal, essentially stopping recurrence before it starts.

Post-surgery recovery at Purdue

About two months after the surgery, the dog was brought back to Purdue for initial observation and analysis. Aside from occasional vomiting, the researchers were pleased with the dog’s recovery. The dog performed well during daily walks and had its medications lessened. The dog did lean to the right a little and had some balance issues, so anti-inflammatory steroids were administered during its Purdue stay.

Six months after surgery, the dog came back to West Lafayette and underwent an MRI screening that Scarpelli was part of. The images showed improvement and no cancerous regrowth.

One Health focus

Scarpelli enjoyed working with his Purdue Veterinary Medicine colleagues. Vanhaezebrouck and Bentley’s veterinary expertise blended well with Scarpelli’s for the project. While those researchers moved on to Texas and Liverpool, England, respectively, the study showed strong collaboration from the team that could impact veterinary medicine abroad.

While most of Scarpelli’s career has worked with human patients or participants, his work with veterinary researchers and clinicians was rewarding. Besides, who wouldn’t want to help someone’s beloved pet live longer and happier?

“Usually, dogs aren’t covered by health insurance. So, they’re not getting any treatment unless we can provide these clinical studies for them,” Scarpelli said. “So that’s another important aspect to it is we get to treat dogs that would otherwise not get anything. That’s another rewarding aspect to the job, and I hope to continue the collaborations like that, whether it’s at Purdue or elsewhere.”

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.