Early involvement in research pays dividends for HHS undergrads

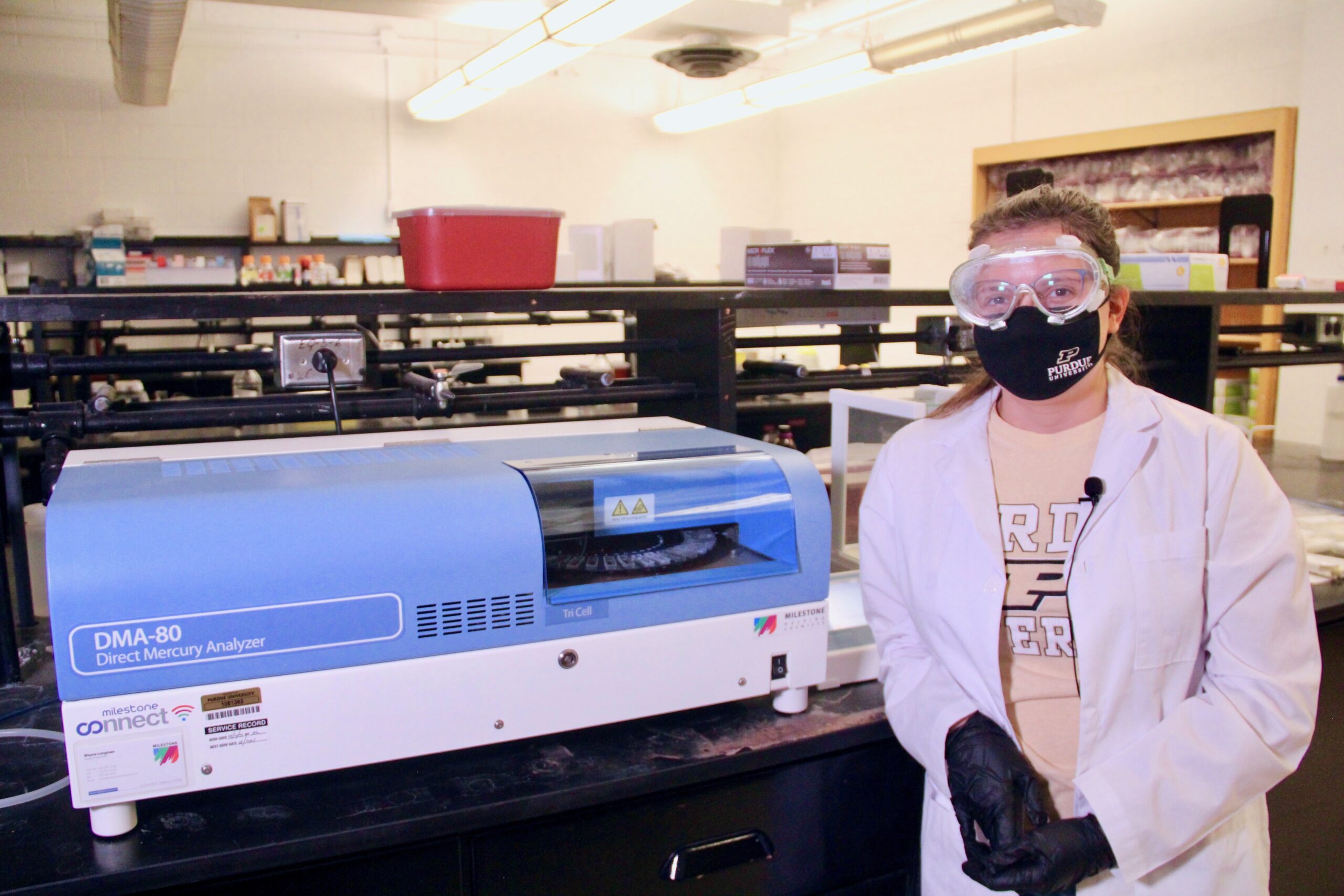

Kiara Smith, a senior in the School of Health Sciences, takes a break from analyzing levels of methylmercury for a research project in Professor Aaron Bowman’s lab.Tim Brouk

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Getting involved in undergraduate research early can pay off after and during students’ years in the Purdue University College of Health and Human Sciences, according to Aaron Bowman, professor and department head of the School of Health Sciences.

Bowman’s research efforts cover multiple projects relating to the human brain. His projects usually involve cells of the human brain grown from pluripotent stem cells cultivated in his labs. Some current work includes studying the chronic and persistent effects of manganese, mercury and pesticide exposures to brain cells.

Bowman, who has pursued better understanding of toxic exposures and neurodegenerative diseases throughout his career, has nine undergraduate researchers in his lab spaces — more than quadrupling the amount since 2018, his first year in the School of Health Sciences.

The students assist graduate students and postdocs, but they also have opportunities to co-author research journal articles and receive collaborative opportunities beyond West Lafayette. Adam Barmash Rubinchik, a junior in Bowman’s labs, spent last summer at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center learning new techniques and soaking up more hands-on lab experience. His early jump into research earned him the opportunity.

“He already knew how to work with human stem cells, and not a lot of undergraduates can say that,” Bowman said. “It was skills he learned as a part-time undergraduate researcher that allowed him to be competitive for a full-time summer experience in a different lab because he had gained that knowledge.”

Working in lab spaces spanning Purdue’s Lilly Hall of Life Sciences and Discovery Learning Research Center, Bowman’s students foster and enhance their learning and opportunities in their futures outside of the lab as well.

“It is clearly a great experience for an undergraduate student to really get a grasp of the underlying research that informs our understanding of human health,” Bowman said. “I want to provide as much opportunity for that as I can.”

‘Nice and healthy’ cells

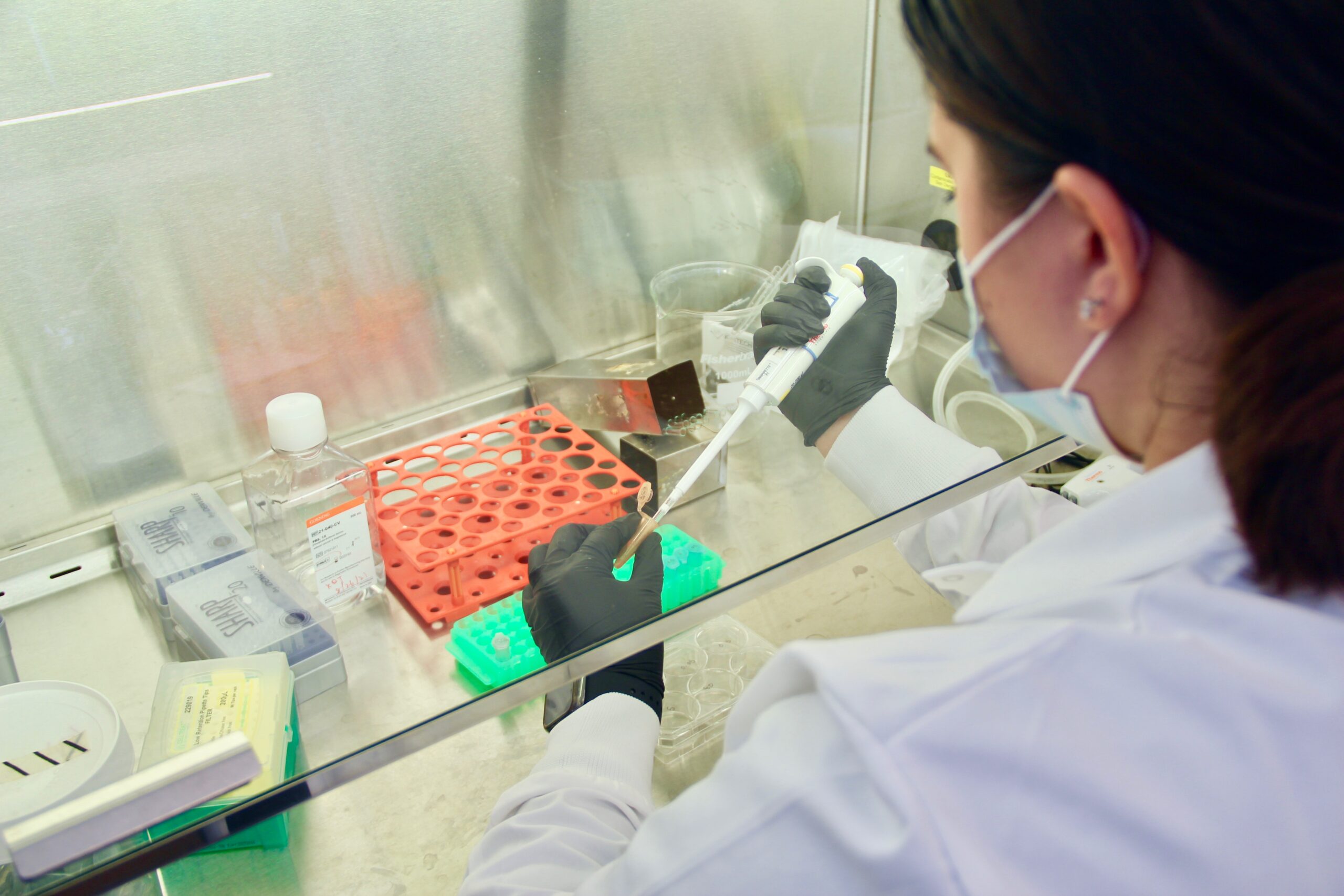

Like a beloved pet, cells must be fed and nurtured in Bowman’s labs. Rubinchik has been busy cultivating cells for his experiment, in collaboration with Health Sciences Associate Professor Jason Cannon’s laboratory, on what effects the Chlorpyrifos pesticide has on human cortical cells, specifically measuring the cells’ glutamate release. Glutamate is a neurotransmitter found in the brain’s nerve cells.

Before exposing them to the pesticide, Rubinchik keeps tabs on the cells every time he logs work in Bowman’s Discovery Learning Center labs. The cells are kept in 24-well plates stacked inside incubators at 37 degrees Celsius with about 5% carbon dioxide. Keeping the cells healthy is crucial to get “baseline” measurements during his experiments.

“I cannot proceed with the experiment if the cells are dying out or they’re feeling disturbed in any way,” Rubinchik said.

The cells are nourished in media comprised of amino acids, proteins and other nutrients to maintain the cells’ health. But to get precise cell functional measurements, the media is replaced temporarily with a more basic saline solution to measure release of glutamate from the cells while still maintaining cell health.

“As the cells communicate and go on about their daily lives, they release glutamate between themselves, which is like their way of having conversation with each other,” Rubinchik said.

The glutamate, an essential communication component to the nervous system, is measured after a timed incubation. Then, the student compares how much glutamate is produced after the cells’ exposure to varying concentrations of pesticide.

“Seeing disruptions or something irregular will tell us a lot about the effect of this pesticide on the human body,” Rubinchik said. “This affects people in big cities, small cities and rural areas because pesticides can make their way down to our drinking water pipelines. Also, these products could get to your average supermarket. Produce might not be fully cleaned and could still have traces of pesticides. You can never tell if it’s going to be enough of an exposure to have negative effects, but it’s always good to look at various concentrations to be safe as possible.”

‘Sparked my interest’

Lily Rosati Yoos works at a hood in Professor Aaron Bowman’s lab. Her project explores the effects of Huntington’s disease on the human brain.Tim Brouk

Huntington’s disease is a genetic disorder that results in progressive cognitive, psychiatric and movement ailments. The disease affects thousands of Americans each year. Lily Rosati Yoos, a junior majoring in health sciences, is investigating if manganese exposure speeds up Huntington’s development in humans. While some manganese is welcome in the body through food, too much manganese breathed in could affect cognition.

Yoos is analyzing the reactions of neurons from a mouse cell line when manganese is introduced. One part of the research includes measuring the cells’ protein levels. To do this, she uses western blot methodology. Cells are filtered into electrophoresis chambers about the size of a lunch box. This technique separates proteins by molecular weight, and Yoos can measure the proteins when they appear as tiny bands after being transferred onto a blotting membrane.

Yoos is marking almost two years in Bowman’s labs. Bowman spoke at one of her classes during her first year about research opportunities and she leapt at the opportunity.

“His project was very relevant to what I’m interested in, particularly neurodegenerative diseases,” Yoos said. “That just sparked my interest and I knew Dr. Bowman seemed like someone I wanted to work with.”

‘Found a passion’

Madeleine Strom, a sophomore studying health sciences, examines a well of microelectrodes.Tim Brouk

Madeleine Strom’s first months in Bowman’s labs were from home. Still, the COVID-19 pandemic did not stop the then first-year student’s early passion for research. She studied journal articles and familiarized herself with Bowman’s ongoing projects.

The preparation was successful as Strom easily transitioned to in-person lab work for her sophomore year, soaking up experiment processes and seeing research at work first-hand. The prep work helped her dig into her current project involving microelectrode arrays (MEA), plates containing 16 tiny microelectrodes in each well. These tiny electronics record neural activity in brain cells.

Strom is utilizing the microelectrodes to study the cells’ reactions to toxins. Once the microelectrode arrays are placed inside an Axion MEA recorder, the data is broadcast to a computer screen, illustrated as wavy lines: The more spikes on the screen, the more neural activity within the cells. Then, with a click of a mouse, Strom can see exactly which cells are most active. Blue fields flash bright, allowing the young researcher to view her cells’ actions in real time.

This work has the goal of understanding how human brains react to various toxins, which falls within Strom’s career aspirations.

“I found it very interesting because its related to what I want to do in the future, which is toxicology. I also found a passion for neurotoxicology specifically after joining this lab,” she said.

Early research exposure

Before she even set foot on campus, Kiara Smith chose health sciences as the start of her journey to become a medical doctor. She knew research would be part of her pre-med quest. When an email promoting undergraduate research opportunities in the School of Health Sciences hit her inbox, she sprang into action, quickly landing in Bowman’s labs.

Now a biomedical health sciences senior, Smith is often stationed in a Lilly Hall lab space shared by Bowman and Carlos Pérez-Torres, assistant professor of health sciences. Since her first year, Smith has studied the neurological effects of manganese and methylmercury exposures through the analysis of human neurons harvested in Bowman’s labs. Both metals can cause cognitive problems in humans if inhaled or ingested.

“Hopefully we can figure out how that can be reversed or prevented in environmental exposures to these metals,” Smith said.

Like Rubinichik, Smith takes great care of feeding her cells with nutrient-rich media but sometimes she adds a little methylmercury into the microscopic meal. This is to measure cells’ reactions to the toxin, which mirrors what might happen when a human eats seafood that contains mercury.

Smith’s analysis of mercury’s effects on the neurons is aided by a DMA-80 Direct Mercury Analyzer machine, which spins up to 40 small quartz boats of the material, about the size of a disposable razor cartridge. This helps her see how much methylmercury is interacting with the neurons — down to the nanogram.

Smith is now the go-to researcher for mercury analysis in Bowman’s labs. She will be training younger students on the DMA-80 technology before her May graduation.

Over the years, Smith has met numerous fellow Health and Human Sciences students who have benefited from research in labs as well as out in the community. The work enhances their experience as Boilermakers while preparing them for careers, graduate school or medical school.

“Whatever your passion is, you can usually find some kind of outlet for that through undergraduate research,” Smith said.

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.