Purdue Health Sciences researchers develop bioaerosol sampler for faster, more accurate virus and bacteria detection

By Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Jae Hong ParkJohn Underwood

While development started before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Aerosol Research Lab of Jae Hong Park, assistant professor in the Purdue University School of Health Sciences, has created patented technology that can collect and analyze bioaerosols rapidly and conveniently in the field environment. Bioaerosols are airborne biological particles that include fungal spores, bacteria and coronaviruses causing COVID-19.

To prevent people’s exposure to bioaerosols, measuring their concentration is the first step. Park’s prototype bioaerosol sampler homes in on adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a compound within cells of bioaerosols. The device is compatible with the swab-based ATP bioluminescence monitor. The monitor quantifies microorganisms on the swab by measuring the light produced through ATP’s reaction with luciferin, an organic substance present in luminescent organisms, such as fireflies, that produces light when oxidized.

This sampler can be used in both personal sampling to measure individual exposure and area sampling.

“It can easily measure the concentration of bioaerosols within 15 seconds,” said Park, whose research was recently published in Environmental Research. “Measuring how much is in the air is the key point.”

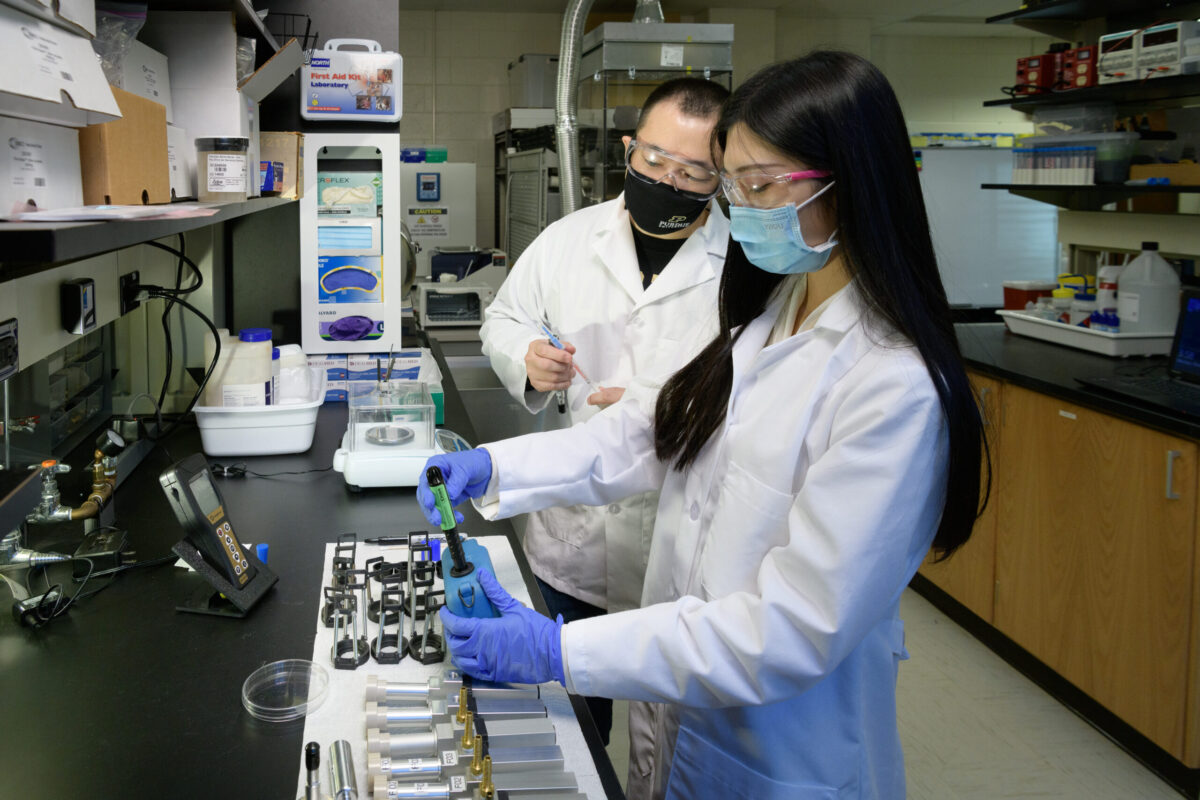

Jae Hong Park, assistant professor of health sciences and left, works with Li Liao, a health sciences PhD student, in creating new bioaerosol detection technology.John Underwood

For personal sampling, the sampler should be located in the breathing zone within 30 centimeters of the nose and mouth. The developed sampler can be attached to the collar or lapel because it is small and light. The sampler utilizes an impactor to collect bioaerosols onto a swab that is originally used for collecting samples from the surfaces or the human. After sampling, bioaerosols collected on the swab can be analyzed by methods such as ATP bioluminescence assay and immunochromatographic assay (ICA). The developed method can show the results in the field, which overcomes the limitation of the conventional methods. The conventional methods are usually time-consuming because they require transportation of samples to a lab, incubation and subsequent analysis.

In further research, the sampler has been combined with lateral flow test kits. Similar to a pregnancy test kit, it is a simple strip kit to confirm the presence of an antigen contained in target pathogens. This study has been funded by NIOSH Pilot Project Research Training Program. In a similar way, the sampler already can be used to detect the coronaviruses in the air, but obtaining the specific lateral test kits and swabs is difficult due to high demand.

Bioaerosols are produced by humans too. With every cough, sneeze and conversation, particles are produced and linger in the air. This has been cemented into the public health conscience for the past year-plus during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has brought more spotlight to Park’s aerosol research.

“By just talking, these droplets are released in the air and may contain a virus,” Park said. “Very tiny droplets can suspend in the air longer and fly longer and then cause infection. We are targeting these tiny aerosols.”

Sampler’s start

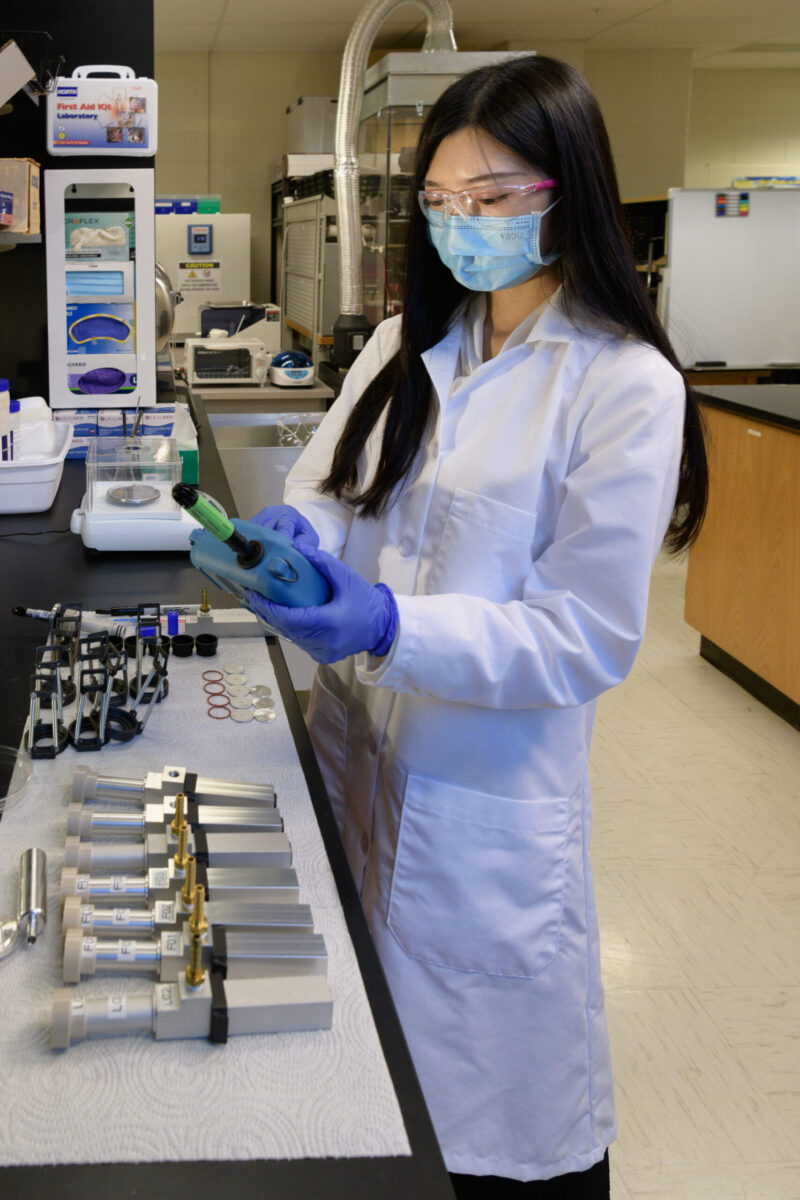

Li Liao, a PhD student in the School of Health Sciences, has been key in the development of a new bioaerosol sampler in the lab of assistant professor Jae Hong Park.John Underwood

Park’s early focus for the sampler was on the detection of bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease, a severe form of pneumonia caused by bacteria in the air from water. He envisioned using the device around bodies of water where workers could be exposed to the disease, from hotel pools to cooling towers.

Soon, the research expanded to other settings where dangerous, invisible inhalants can be found. Li Liao, a PhD student in the occupational and environmental health science program, was key in researching, testing and designing the sampler in Park’s lab. She tested the device in agricultural settings around Indiana, detecting some potentially harmful bioaerosols in animal stock facilities. She tested around the horse stables as well as indoor areas where people live.

“We found very high concentrations of bioaerosols in agricultural settings,” Liao said. “It is generated from the animals and feed and can be inhaled by workers.”

Liao compared her sampler to others, which overloaded in the farm settings. Her sampler was still able to quickly detect what and how much was floating around and getting breathed in.

Targeting the market

By collaborating with healthcare companies, Park aims to mass-market his bioaerosol samplers, with hospitals being the initial target. Before that, he wants to streamline the device by making it lighter, less expensive, and disposable like COVID-19 or pregnancy tests. Prototypes are mostly made of aluminum. He hopes to make the sampler plastic, with the ultimate goal of bettering occupational health.

“Usually, company owners don’t like to spend much money on these kinds of exposure assessments,” Park explained. “I need to make a cheaper way and less complex method.”

While the COVID-19 pandemic finally crawls closer to a possible conclusion, another pandemic could unveil itself in the near future. By then, Park’s sampler could be vital in detecting the next coronavirus or other deadly, invisible airborne pathogens.

“This technique can be used in a variety of industries — and not just protecting humans but animals and products as well,” Park said. “In healthcare facilities, detecting pathogenic bioaerosols could save the lives of patients and the healthcare workers. They’re fighting in the hospital in their own way. I want to protect them in my own way.”

The Purdue Office of Technology Commercialization has received a patent in this technology from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Park and Liao’s bioaerosol sampler is available for partial licensing with the tracking code of 2019-PARK-68422. Contact Abhijit Karve for more information.