CALC Outstanding Professor Award

|

Dr. David Waters, PhD, DVM, is the recipient of this year’s CALC Outstanding Professor Award. Dr. Waters is Director of the Center for Exceptional Longevity Studies at the Gerald P. Murphy Cancer Foundation, a not-for-profit research institute located in West Lafayette, Indiana. From 2000-2014, he served as Professor of Comparative Oncology and Associate Director of the Center on Aging and the Life Course at Purdue University. He received his DVM from Cornell University (1984) and his PhD from University of Minnesota (1992).

Since 2008, he has led the research team conducting the first systematic study of exceptional longevity in pet dogs. The research hinges on the idea that pet dogs with extreme longevity - equivalent to humans who live to be 100 years old - offer a valuable scientific opportunity to uncover important clues to understanding what it takes for pets and people to age more successfully and avoid cancer. His expertise as a One Health-minded translational researcher is evidenced by publication of more than 100 peer-reviewed scientific papers in high-impact journals, including Aging Cell, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Journal of Gerontology, Carcinogenesis, Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention, and Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

Dr. Waters is also an expert on the comparative aspects of prostate cancer in men and dogs, selected as one of the 100 scientists who formulated the scientific direction of the prostate cancer research agenda of the United States in 1997. In 1999, under the mentorship of Dr. Ken Ferraro, he received a prestigious Brookdale National Fellowship for Leadership in Gerontology and Geriatrics. He is the only veterinarian – one of 130 scientists worldwide – to be recognized as a Fellow in the Biology of Aging by the Gerontology Society of America and served as a member of The National Academies of Sciences – Keck Futures Initiative Scientific Panel on Extending Human Healthspan. In 2017, his paradigm-shifting research on the cancer-fighting trace mineral selenium was recognized by an invitation to speak about U-Shaped Thinking at the Celebration of the 200th Anniversary of the Discovery of Selenium convened at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden.

Dr. Waters is an award-winning teacher and since 2011 has served as faculty for the NIH’s National Cancer Institute Summer Curriculum on Cancer Prevention providing instruction on principles of cancer prevention to more than 500 scientists-in-training from 35 countries. In 2017, as part of a creativity project with collaborators in Australia, Dr. Waters published a manuscript exploring how cultivating an attitude of language precision can catalyze creative excellence in scientific discovery and education. His 2013 TEDx talk, “The Oldest Dogs as Our Greatest Teachers: Get the Words Out of Your Eyes”, highlights the innovation of studying the oldest living pet dogs, and underscores how our use of language limits scientific discovery and influences how we respond to new information.

Dr. Waters currently teaches the CALC-required course Biology of Aging. We caught up with Dr. Waters and interviewed him about his teaching philosophy and methods.

Why do you consider the Biology of Aging to be of fundamental importance to graduate education?

There are many barriers to effective interdisciplinary training. One such obstacle to graduate-level training in gerontology is the challenge of making the biology of aging accessible to non-biologists. The “Biology of Aging” course offered to CALC students attempts to hurdle this barrier by offering a contemporary perspective on the kinds of ideas biogerontologists wonder about. Students are exposed to individual lines of inquiry that are leading to discoveries about the aging process. The biological underpinnings of healthy longevity are not provided as a laundry list of facts and theories, but instead as a moving target – a field in flux, underscoring critical gaps in our understanding. The ability to identify key linkages, a willingness to blur disciplinary boundaries, and the construction of conceptual frameworks derived from multiple disciplines are encouraged. At the very least, students are drawn into a genuine dialogue about the biology of aging. And by placing emphasis on cultivating an attitude of precision with language, students are provided a powerful tool – a rich, cross-disciplinary vocabulary that bolsters their confidence in becoming productive members of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teams.

What do you find to be the most fulfilling aspect of teaching gerontology graduate students?

It is a great privilege to create challenging learning opportunities for the exceptional scholars-in-training who are the students of CALC. Each student brings to the table a wildly different set of academic experiences and aspirations – the kinesiologist pursuing a molecular biology PhD sits next to the sociology PhD candidate with no biology since high school. On the surface, this might sound like a recipe for disaster. In my experience, however, this heterogeneity creates an unprecedented happy opportunity. I attribute this good luck in large part to the fact that students at Purdue pursuing the Dual-title PhD in Gerontology have exceptional expectations. Biologists and non-biologists alike are looking for a vehicle to move them beyond their area of specialized training to take a more integrated view of the aging process. It is gratifying to watch a student starting out as a specialist-in-training dive headlong into experiences intended to balance, broaden, and eventually transcend her specialized ways of seeing. The challenge for me is to further fuel their fever for such “out-of-silo” classroom encounters. In some cases, graduates who become faculty share that they incorporate aspects of their “Biology of Aging” experience into the courses they design and teach to their own students. That is really nice.

What is your educational philosophy?

An overarching goal of mine established pretty early in my career was to become a discoverer, then teach discovering. A goal of this nature led me to embrace certain principles, such as Cowell’s teaching of adjustability rather than adjustment, which dovetailed so nicely with Emerson’s notion of education as provocation, rather than indoctrination. This kind of thinking led me to accent the value of an awareness of limits – the limits of perception, thought, and language. The primacy of introducing these limits to students placed a premium on providing learning opportunities whose value to the student traveled well beyond the subject matter. Increasingly, I moved toward crafting learning opportunities that placed a high priority on developing an attitude of precision with language. I could immediately see the payoffs from using this approach. Students begin to realize that we see the world through our categories, then begin directing their energies toward becoming more skilled category-makers. And looking to deepen their relations with language, students were discovering the rich prospect of making new words – the process of neologism – as a vital act of scholarship that could address some of the obstacles to their scientific advance. As Gadamer wrote, “Whoever has language 'has' the world.”

So how does this educational philosophy manifest itself as action in your classroom?

A fly-on-the-wall look inside the classroom of the “Biology of Aging” would find students finding themselves engaged in a process of personal growth and meaning-making. Initial lectures provide vocabulary, enabling students to enter the subject matter. Then, a collection of scientific papers are read by each student prior to group discussion. Students read these papers and form their own abstractions – take-aways that each student sees as subjective and idiosyncratic. Students create understandings from these starting points, which are their own products, not facts handed to them. Discussions enable students to see the processes of fellow students and the instructor as they share their own thoughtful attempts to order and interpret new information. Students acquire new attitudes during this process because they experience firsthand how attitudes (such as tolerance to opposing results) advantageously modify their method. Understanding is advanced individually through this process of iterative, collective meaning-making and personal preparedness.

Students see that using language skillfully can disconnect oneself from preconceived notions, no longer blinded by old stories, readied for the next provocation. Eventually, students begin to realize that standing in between them and the scientific problems they are so passionately trying to unriddle are the words used to describe or categorize those problems. For most students, this real-life circumstance of in-betweeness has never occurred to them before. Together, we celebrate moving one step closer to becoming discoverers, developing a readiness for a lifetime of seeing and reporting. And as the semester closes, student progress is evaluated using an oral final examination format that compels each student to reflect upon and express the extent to which the past 13 weeks have heightened their own readiness.

Could you share some of the key academic sources that have shaped your own personal growth as an educator?

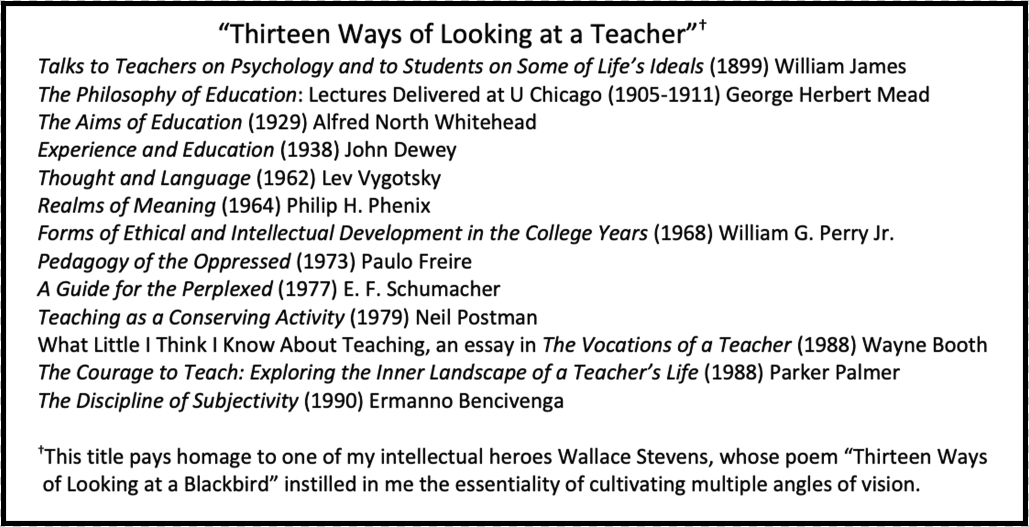

I can think of thirteen seasoned books – each written at least 30 years ago and representing a 90-year sampling of intellectual fare – that have broadened and sharpened my perspective of the teaching-learning space. Although unlikely that these volumes are lighting up many of today’s hallway exchanges, these “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Teacher” contain the kinds of provocations that can provide the fine timber that unfinished teachers and teachers-in-becoming could use to construct their own luminous library of ideas.

|

Selected Manuscripts by Dr. Waters

Waters DJ and LS Waters. On the self-renewal of teachers. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 2011; 38: 235-41.

Waters DJ. The paradox of tethering: Key to unleashing creative excellence in the research-education space. Informing Science 2012; 15: 229-245.

Waters DJ. On cultivating an attitude of precision with language: An uncommon prescription for conditioning creative excellence in scientific discovery and education. TEXT 2017; Special Issue 40: Making it New: Finding Contemporary Meanings for Creativity.

Waters DJ. As if blackbirds could shape scientists: Wallace Stevens takes a seat in the classroom of interdisciplinary science. The Wallace Stevens Journal 2017; 41: 259-69.

Waters DJ. Devising a new dialogue for nutrition science: How life course perspective, U-shaped thinking, whole organism thinking, and language precision contribute to our understanding of biological heterogeneity and forge a fresh advance toward precision medicine. Journal of Animal Science 2020; 98(3): skaa051.