Learning Objectives

From reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the role of critical thinking in plant problem diagnosis

- Describe the basic process of diagnosing plant problems

- Understand how to apply this process to real-world problems

- Recognize when the process needs to be modified to address specific problems, and how to modify the process to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Introduction

The ability to correctly diagnose plant health problems is an important skill for the practicing plant health care practitioner. Diagnosing plant health problems requires an investigative approach, similar to a crime scene investigator working a crime. Like a criminalist, you need to synthesize fragments of information to reconstruct the event(s) that produced the plant damage. Proper plant health diagnosis requires both logic and critical thinking. Critical thinking is an essential component of diagnosing plant damage in that it requires the diagnostician to:

- gather and assesses relevant information

- think open-mindedly and objectively evaluate observations, assumptions and implications about the problem

- formulate crucial questions clearly and precisely

- develop well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, and evaluate them against the information obtained.

Ultimately, the process of diagnosis distills all the information obtained regarding the problem by formulating good questions to glean key pieces of information, necessary to come up with the most likely, or best explanations.

It is important to stress that critical thinking is a skill that is honed over time, not developed immediately. By following a stepwise process you should be able to develop this skill and personalize it into a system that works best for you. The steps of this process include:

- Proper host identification

- Symptoms

- Problem determination

- Signs

- Process of elimination

- Determining the nature of the problem

DEVELOPING A PROCESS

Proper host identification

The first step of every crime story is the identification of the victim. Diagnosing plant damage is no different: Correctly identifying the host plant is essential for successful diagnosis. One of the biggest hurdles to proper plant problem diagnosis is plant identification. Even after “proper” identification, additional problems become apparent, particularly regarding the confusion between common names. One of the best examples of this is “cedar”, as it may refer to true cedar (Cedrus), Eastern red cedar (Juniperus), white-cedar or arborvitae (Thuja), Incense-cedar (Calocedrus decurrens), Port-Orford-cedar (Chaemycyparis) and Japanese-cedar (Cryptomeria). Although all of these plants are regularly referred to as cedar, they are attacked by many different insects and pathogens. Mis-identifying the host in this instance can result in focusing upon an incorrect subset of causing and ultimately, in a misdiagnosis.

One problem with host identification is that it leads to assumptions regarding the nature of the problem. Not every problem on white pine (P. strobus or P. monticola) is white pine blister rust. Proper host identification is only the beginning. Knowing what is normal (or doing the background research to determine what is normal is essential). By comparing the “normal” healthy plant with the plant in question can clarify what is, or is not “normal.”

Figure 1. Different types of “cedar”: (TOP L to R): Deodar cedar (Cedrus), Japanese-cedar (Cryptomeria spp), incense-cedar (Calocedrus decurrens); (BOTTOM LtoR): Port-Orford-Cedar (Chaemycyparis lawsoniana), Eastern-red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), white-cedar (Thuja plicata).

Common names are often common to specific areas: Nyssa sylvatica is called sourwood, tupelo, and blackgum, depending upon which part of the country you are located. Furthermore, some common names are misleading: Climbing gloxinia (Aserina) isn’t a gloxinia (Sinningia speciosa) any more than a flowering maple (Abutilon) is a maple (Acer).

Problem determination

Identifying the host can allow you to quickly recognize nonproblems: Baldcypress (Taxodium) and dawn-redwood (Metasequoia) are two species of deciduous conifers, meaning that the regular, seasonal loss of foliage is normal; Agastache ‘Gold Fortune’ is a naturally yellow plant, and not suffering from nutritional problems, and the ‘Schwedler Maple’ will not remain red all season long like Acer ‘Crimson King’ but will instead “green up” over the summer.

Figure 2. Normal vs abnormal needle drop.

(TOP Left) – Normal. Baldcypress (Taxodium) is a deciduous conifer that loses its needles every year. (TOP Right) – Abnormal. This kind of random needle loss suggests a significant problem. In this case, most of these newly transplanted Arborvitaes did not survive.

Figure 3. Normal fall needle drop. This is a seasonal occurrence. The fact that all these Pine trees are similarly affected is a key clue in the diagnosis of this ‘problem’.

Figure 4. This is abnormal – New leaves are lost. This picture shows how the new leaves have half the needle length of the previous year’s growth, suggesting additional stress.

Many plant health problems aren’t problems at all, at least not to the plant! Other examples: Echinacea‘Double Decker’ which naturally looks as if suffering from aster yellows; the reproductive structures on the underside of fern fronds that are commonly mistaken for rust, or the failure of dwarf selections of trees not reaching the expected height is often attributed to disease. Many variegated plants have foliage that can be mistaken for virus infection. All of these examples demonstrate the importance of knowing what the normal plant looks like prior to “diagnosing” a problem.

Figure 5. The youngest leaves of some rhododendrons are often covered in small hairs, which can be mis-identified as powdery mildew. The plant in the photo above (right) has powdery mildew. The plant on the left does not.

Process of elimination

Certain plants are associated with common problems. Ash trees get attacked by emerald ash borer; elms are prone to Dutch elm disease. By focusing on the host, a majority of potential problems are quickly eliminated because they simply do not attack the host plant in question (Maples do not get emerald ash borer, and elms do not get oak wilt). To use an animal analogy: When hearing hoofbeats in North America, don’t think it is coming from an African zebra! Focus on the most likely explanations. However, another common diagnostic pitfall is to assume just because a plant is a certain species, it automatically has a common problem. Just because a plant is a white pine (P. strobus or P. monticola) doesn’t mean the default diagnosis is white pine blister rust. It may be, but additional diagnostic steps are necessary for confirmation, namely identifying the symptoms and signs of the problem.

Defining the symptoms of the problem

Symptoms define the changes in a plant’s appearance, growth, or development in response to a problem. They reveal a disruption in the normal plant function that causes a loss of structure, appearance, or economic value. Disease or insect damage occurs when an organism damages the plant or prevents it from achieving its genetic potential. The plant responds to different stresses in remarkably similar fashion: chlorosis (turning yellow), necrosis (dying), scorching, cankering, distorting, rotting, etc. Because plants often respond the same way to different problems, basing a diagnosis on only one or two symptoms can result in an incorrect diagnosis.

Figure 6. The lavender shows foliar dieback which was easily explained when the roots were examined.

Before undertaking the subsequent steps, it is important to emphasize that, with few exceptions, only half the plant is visible. However, root problems, particularly in the urban landscape, nursery or greenhouse, are commonly under- or misdiagnosed. Whenever possible, examine the roots of any affected plants to correctly gather and assess all the relevant information! Foliage dieback symptoms can occur due to root damage. When examining foliar problems, examine the plant (leaves, stems, twigs, branches, main stem) down toward the roots to determine the location of the primary damage. The lavender (Figure 6) shows foliar dieback which was easily explained when the roots were examined.

Identifying Signs

Signs are evidence of the biologic agents of plant disease. The presence of signs is necessary to make an accurate diagnosis. The actual insect, its exoskeleton, frass, or fungal mycelia, fruiting bodies, and bacterial ooze are all signs. However, not all signs are visible to the unaided eye (macroscopic). In fact, many aren’t. Viruses, for example, are only visible through an electron microscope. Disorders caused by abiotic stresses do not have associated signs.

Figure 7. Signs are the physical presence of the organism. Top: (Left) Cluster cup rust; (Center) Spider mite eggs: (Right) Hemlock wooly adelgid Middle: (Left) Aphids, adults and young; (Center) Ganoderma conk; (Right) Swallowtail butterfly caterpillar Bottom: (Left) Black knot gall; (Center) Insect feces; (Right) Slime mold

From the IAH Glossary: To be certain of your understanding, here are definitions…..

- Abiotic Disease – an abnormal condition of a plant that is caused by a non-infectious agent. i.e.; environment, people, etc. Often referred to as “People-Pressure Diseases.”

- Biotic Disease – an abnormal condition of a plant caused by a living micro-organism

Distinguishing Between Abiotic and Biotic Agents

Both damage pattern distribution and the period of time for damage development are important clues in determining between abiotic disorders or biotic damage. However, additional clues are often needed to make a conclusive diagnosis—but not always…

Figure 8. The problem here has nothing to do with any micro-organism. Clearly, this would be considered as an abiotic disorder..

Examine patterns

In the urban landscape, patterns may not be as obvious as in a nursery or greenhouse, however, nearby plants should be examined to see how problems spread. Problems that spread between unrelated plants in a single location suggest an abiotic disorder. Damage caused by an herbicide will affect leaves of a specific age, or facing a specific direction. Damage caused by potato leaf hopper on maple affect the newest growth on some varieties of maple in late spring and early summer. Black spot of rose will only infect the susceptible roses and not nearby clematis. Abiotic factors such as frost damage occurs over larger areas (from frost pockets to entire geographic regions), and affect portions of the plant at a certain age (all the flowers that were open during the frost event) or exposure (e.g., leaves on one side of the plant).

Figure 9. Abiotic disorders often, but not always, present symptoms with a pattern, like this lawn mower injury.

Figure 10. (TOP Left): Daylilies are more resistant to salt toxicity than yews. (Right): The fact that only one side of this tree shows damage is indicative of an abiotic problem. Biotic problems rarely have distinct lines of demarcation. (BOTTOM Left): Late blooming crabapple flowers (called rat-tail blooms) escaped the freeze that damaged the young leaves.

Examine the development of the problem

Abiotic disorders often (but not always) develop symptoms rapidly, as in the case of chemical damage. Misapplication of herbicide results in symptom development or death over the course of several days. Even the most virulent of plant pathogens, like Dutch elm disease, takes weeks if not months to kill a tree. Emerald ash borer has an incubation of several years. The herbicide Roundup (Glyphosate), when applied to an herbaceous plant will cause plant death in as quickly as three days. However, 2,4-D herbicides may take several weeks to completely kill.

Abiotic factors, such as chemical application or mechanical injury, often result in immediate (acute) damage to the plant and do not spread to other plants with time. Other abiotic factors can cause a slow debilitation over time (chronic), such as iron chlorosis, which doesn’t kill the plant outright, but will result in plant death eventually.

In general, abiotic disorders aren’t progressive, but chronic or long-term problems (drought, regular seasonal salt damage, iron chlorosis) can give the appearance of a progressing problem. The key here is to distinguish between the problem getting progressively worse with one plant, or spreading between closely related plant species.

Abiotic disorders can present in a variety of ways: Sudden and extreme environmental events, like wildfires, tornadoes and hurricanes are fairly obvious.

Other extreme events, like drought, flood or salt damage after a hurricane, may take many years before symptoms manifest themselves.

Figure 11. (Left): Deer browse on Hosta. This damage literally showed up “over night.” (Right): Iron chlorosis in Pin Oak. Newest leaves are showing more severe symptoms than older leaves, and example of a chronic abiotic problem producing progressive symptoms. However, the fact that only the pin oak is affected in this landscape indicates an abiotic disorder.

Figure 12. Trees in the aftermath of hurricane Irene (Photo by National Geographic.) This is another abiotic

Figure 13. A Christmas tree farm will take years to recover postflood, if it ever will. (Photo by Bob White.)

Determining the nature of the problem

If the damage seems progressive, and abiotic disorders have been ruled out, closer examination of symptoms and signs is necessary to diagnose the problem. Unlike an agricultural field composed of large areas of a single crop, nurseries, greenhouses and landscapes are often fractured. As a result, broad patterns of problems may not be immediately evident to the untrained observer. This makes the process of identifying the nature of the problem that much more difficult. Over 70% of all plant health problems are abiotic, and caused by non-living factors such as drought, flooding, temperature extremes, issues of nutrition or toxicity, mechanical damage or chemical damage. The remainders of plant health problems are biotic, meaning that living organisms, such as vertebrate pests, invertebrate pests, and pathogens, cause them. If we suspect that the problem is biotic in nature, we use symptoms and more conclusively, signs, to distinguish between pathogens and insects and identify the causal organism. Remember: Just because the organism is present doesn’t mean that it is the root of the problem. Most insects and fungi do not cause plant health problems!

Living organisms generally multiply with time, produce an increasing spread of the damage over a plant or planting with time, and are progressive.

Living organisms are specific, i.e. damage may be greatest on or limited to one species of plant. Because living organisms grow and multiply over time, the damage they inflict is progressive as well. Damage caused by biotic organisms spreads from the initial point of attack to other areas of the plant. This is a key diagnostic point that distinguishes abiotic from biotic problems. Notice how rust on Hypericum (Figure 14) and Septoria on Rudbeckia (Figure 15) show how disease radiates from a single point and spreads through adjacent plants, but leaves adjacent, unrelated plants unaffected.

Biotic problems are fairly host specific, meaning that the organism causing Verticillium wilt on a Japanese maple is not causing the wilt on the adjacent Japanese pine because pine cannot become infected with Verticillium. Something capable of infecting both Japanese pine and Japanese maple should suggest to the diagnostician something abiotic—extreme weather conditions, root damage, chemical damage. In the absence of signs, or if the evidence points to a problem that is abiotic in nature, additional questions or observations are needed to identify the source of the problem.

Distinguishing Between Foliar Problems

No part of the plant is more obvious than foliage, where most problems are observed. Fortunately, few foliar problems regularly result in the death of the plant. However, many root and stem problems are first visible as foliar damage. Thus, care must be taken in evaluating foliar problems to adequately identify the underlying cause.

Figure 16. This type of damage is referred to as spiral damage. Not all trees are as obvious as the one on the right regarding spiral growth. The blue spruce (Left) actually suffered from root damage, but the spiral stem resulted in symptomatic branches with brown needles spiraling up the main stem. Many foliar problems go misdiagnosed due to failure to examine anything other than leaves

Entire or major portion of top dying

If all, or major portions of a tree or shrub dies, one should suspect a problem with the roots. Trees do not always grow “straight up or down” and spiral growth, or other disruption of the cambial tissue, as shown in Figure 17, can result in unusual patterns in a tree’s canopy.

Figure 17. Frost cracks (RIGHT) (also referred to as southwest winter injury or sun scald), or other physical damage to the trunk or stem of a plant can severely impact vascular system integrity

Consider, too, that the vascular system, which transports nutrients, moisture and oxygen from the roots to the foliage can be disrupted, sometimes fatally, by other abiotic disorders. Stem girdling on a tree can be caused by failure to remove rope or twine (especially synthetic types) from around the trunk at time of planting B&B trees. Likewise, the same problem can occur due to bark and cambium damage from careless lawn mowing or weed-eater use, or from rodent damage.

Frost cracks (also referred to as southwest winter injury or sun scald), or other physical damage to the trunk or stem of a plant can severely impact vascular system integrity (Figure 17, Right).

Sudden decline

Sudden decline is usually the result of abiotic disorders, singularly or in combination. Plants may recover, or may continue to decline until death. The Pines pictured in Figure 18 display Sudden Decline disorder.

Figure 18. The symptoms pictured here developed in August (Top) and the tree was dead by December (Bottom).

Physiological Disorders

Physiological Disorders affect certain plants that regularly drop leaves in response to summer drought. Both birch and tulip-poplar regularly defoliate in late July or August. The abscission of the trees oldest leaves is a protective mechanism that reduces the tree’s water loss and protects it from further stress.

Figure 19. Tulip-poplar and Birch are two species of trees known to undergo foliar reallocation, the regular loss of the oldest leaves in summer to prevent water loss.

Multiple branch death

Root or vascular problems should be suspected when a tree develops multiple branch deaths. One exception to this rule is fire blight.

Other disease, like fire blight, can almost appear abiotic due to the rapidity with which they develop. This ‘Gala’ apple, a highly susceptible variety, also suffered severe hail injury (Figure 21). The apple trees in the background are a different (and less susceptible) variety.

Figure 20. Verticillium wilt on maple (Left) and characteristic symptoms on symptomatic branches (Right) displaying “streaking” when cross-sectioned. Diseases like verticillium will show a gradient of symptoms as they develop over time.

Figure 21. This ‘Gala’ apple, a highly susceptible variety, also suffered severe hail injury. The apple trees in the background are a

different (and less susceptible) variety.

Remember, too, that the degree of resistance to a disease can change over time. This includes the resistance of a pathogen to a pesticide (See IAH Chapter 9) as well as the genetic resistance of a particular plant species or cultivar to a specific disease. For example, ‘Adams’ Flowering Crabapple was once listed as ‘highly resistant’ to Apple Scab. However, in recent years, ‘Adams’ has displayed increasing susceptibility to scab. Many pathologists believe this is a result of changes within the pathogen itself. Thus, it may be more realistic to consider a plant’s tolerance of a disease rather than it’s resistance to it.

Single branch dying

The death of a single branch (called a flag) is commonly due to mechanical damage, or early infection by canker pathogens. The damage to the Redbud in this photo was caused by Botryosphaeria canker, a problem frequently encountered on Redbuds (Figure 22).

Figure 22. The damage to the Redbud in this photo was caused by Botryosphaeria canker, a problem frequently encountered on Redbuds.

Foliar chemical injury pattern on leaf

Spots are uniformly distributed across the leaf surface; Lesion color and size are often uniform (Figure 23). The margin between affected and healthy tissue is usually distinct and lacking any chlorotic (yellow) margins. The pattern of injury does not spread or increase with time. Usually, multiple species of plant are affected.

Foliar injury due to root uptake that results in distortion

Weed and feed products are composed of fertilizer and 2,4-D based herbicides. Certain plants (redbud, grape, hardy kiwi, elder, smoketree) are especially susceptible to this chemical. Leaves will curl as a result of exposure, even application in nearby yards (Figure 24).

Sublethal, fall application of Round-up can also result in the appearance of foliar problems the following spring, as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25. Sublethal, fall application of Round-up can also result in the appearance of foliar problems the following spring,

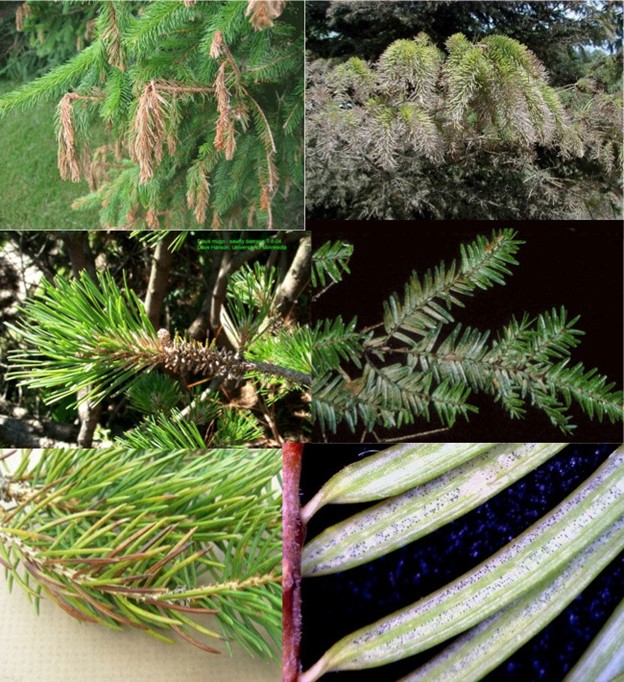

Diagnosing foliar problems in conifers

Conifer needle death can result from a variety of factors. One of the most common, and least fatal is normal fall needle drop, when the oldest needles on the tree are shed (Figure 26 Left). When needle death is limited to the tip of the needle and appears in a uniform pattern across the plant (Figure 26 Right), abiotic problems such as air pollution, freeze damage, drought, or nutrient toxicities should be suspected. As with abiotic disorders in other plants, only leaves or needles of a specific growth period are affected with sharp margins between damaged and healthy tissue.

Figure 26. Photo to left is characteristic needle loss affecting older needles. The photo on the right shows scorch, that is affecting the tips of the newest needles.

When organisms like fungi, insects, and other invertebrates damage needles, injury occurs in a random pattern. Careful inspection of needles with a hand lens may reveal fungal fruiting bodies, insects, or spider mites still present on needles.

Foliar Damage in Conifers

Figure 27. (TOP): Drought stress (Left) or freeze damage can result in wilty tips, affecting new growth throughout the plant. This is contrasted to Trimec damage on spruce (Right), which affects both new and old growth. (MIDDLE): Pine sawfly damage results in needles being half-eaten (Left). This type of insect feeding is distinctly different than the stippling caused by spider mites (Right). (BOTTOM): Foliar diseases on conifers, which results in scattered dead and dying needles throughout the branches on the tree (Left), but are often more severe on older needles, and needles held closer to the stem of the tree. Signs like the pycnidia of Phaeocryptopus (Right) aren’t always so obvious!

Foliar symptoms that indicate problems of the root or vascular systems

Drought stress, root rot, vascular wilts and root uptake of herbicides can result in symptoms of scorching, as shown below (Figure 28).

Improper pH of the potting medium is another common culprit, as seen on this fuchsia leaf (Figure 29).

Foliar symptoms that indicate problems of the root or vascular systems

Drought stress (Figure 30) , root rot, vascular wilts and root uptake of herbicides can result in symptoms of scorching.

Figure 30. Bacterial leaf scorch in oak (Left, photo by Ann Gould) and foliar symptoms in maple. The cause of this problem is a vascular disease. However, symptoms are first apparent in the foliage of the infected tree or shrub (Right).

Distinguishing between pathogens and insects that cause foliar damage

Remember: Symptoms are the plants response to damage. This damage modifies the plant’s appearance. Signs are presence of the actual organism or evidence directly related to it; visual observation of the insect on the leaf, presence of fungal mycelium, spores, insect egg masses, insect frass, mite webbing, etc. Signs can be used as clues in identifying the specific living organism that produced the plant damage. A combination of clues from both symptoms and signs are required for preliminary distinction between pathogen and insect-mite damage. Symptoms of common plant and insect problems are included, with “look-alikes” placed closely together whenever possible.

Figure 31. (TOP): Thrips damage on osteospermum (Left); Rose sawfly on unopened rose flower (Right). (BOTTOM): Southern blight on bulb sheath (Left); Tomato spotted wilt virus on bee balm (Right).

Symptoms And Signs Of Foliar Problems

Insects, invertebrates, and pathogens cause a variety of obvious foliar problems in plants. The symptoms may be obvious, but the causes may be less so. Begin by trying to evaluate the type of damage (damage from chewing or from sucking mouth parts, pathogen problems) and the location of the damage. Damage may be on:

- parts of the leaf

- leaves only

- leaves and petioles

- damage progressing from leaves into the twigs and branches

Symptoms that are found on all the leaves are probably the result of another problem (abiotic disorder or root failure). It is important for plant diagnosticians to always examine the affected plant in its entirety before arriving at any diagnosis!

The location of the feeding damage on the plant caused by the insect’s feeding, and the type of damage (damage from chewing or from sucking mouth parts) are the most important clues in determining that the plant damage is insect-caused and in identifying the responsible insect.

Diseases are often more challenging to the new diagnostician because many of the causes of disease are microscopic. Diseases cause symptoms of yellowing, distortion or even plant death. Common diseases include powdery mildew; rust; scab and spot; blotch, blight, or anthracnose; blister or curl; needle cast; sooty mold; and galls. Signs of fungal disease include thread-like fungal growth, or fungal fruiting bodies, which can be large mushrooms or shelf fungi to microscopic structures that cannot be easily observed.

Entire Leaf Blade Consumed

Entire leaf blade consumed by various caterpillars, and larval stages of wasps (known as sawflies), and adult beetles.

Figure 32. (TOP): (Left): Dogwood sawfly and damage. Bottom: (Left): European Pine sawfly. Compare to Japanese beetle skeletonization of leaves (RIGHT – Top & Bottom)!

Distinct Portions of Leaf Missing

Figure 34. (TOP): Circular holes cut from leaf and flower margin (leaf cutter bee adult): (MIDDLE): indistinct holes cut from margin of leaf by black vine weevils (Left) and rose sawfly (Right). (BOTTOM): Long holes cut between Hosta leaf margins (Left), probably caused by slugs, and small randomly scattered holes (Right) in leaf, possibly caused by earwigs.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery Mildew describes a type of fungal disease that coats leaf (and even stem, flower and fruit) surfaces in a characteristic white, powdery substance (Figure 35). There are hundreds of different powdery mildew species; however, most species are fairly host specific — the powdery mildew on lilacs only infects lilacs, the powdery mildew on roses only infects roses, and so on — of course, like most things, there are exceptions, like this infection on Physocarpus (Figure 36).

Leaf Scab and Leaf Spot

These diseases are characterized by discrete lesions that discolor and die (or, become necrotic). With some of these diseases, the dead tissue is contained and removed from the leaf, resulting in a “shot hole” appearance. Common “shot hole” diseases are often observed on cherry and ornamental cherry trees.

Figure 37. ABOVE): (Left): Apple scab on Malus (Right): Septoria leaf spot on Cornus stolonifera (BELOW): Tar spot on maple.

Rust

These diseases form yellow or orange pustules on the stems and leaves of infected plants (Figure 38). Some rusts only attack leaves, but others can attack stems, resulting in galls or cankers (See stem cankers). Insect eggs can be mistaken for rust pustules, and vice versa.

Leaf Surfaces Damaged

Figure 39. (TOP): “Skeletonization” of leaf surface by Japanese beetles. (BOTTOM): (Left): Pear slug sawfly on Cotoneaster; (Right). Privet thrips

Spotting or Stippling

Spotting or Stippling result from localized destruction of the chlorophyll within individual cells by the injected enzymes where sucking insects feed.

Figure 40. (TOP Left): Spider mites on Spruce and (TOP Right): 4-Line Plant Bug damage. (Bottom Left): Spider mite damage on Burning Bush; (Bottom Right): Lacebug damage on Sycamore.

Anthracnose

These diseases begin as spots, but spread down the leaf veins, into the leaf’s stalk (or, “petiole”), and into the plant’s woody tissue.

Figure 41. (TOP Left): Horse-chestnut blotch; (TOP Right): Ivy anthracnose on Hedera helix; (Bottom): Sycamore anthracnose (Left); Dogwood anthracnose (Right)

Leaves “rolled”

Leaves that are tied together with silken threads or rolled into a tube often harbor leafrollers or leaftiers, i.e. omnivorous leaftier. (Figure 42)

Leaf Blister or Curl

Symptoms of leaf blister or curl are regularly found on ornamental peaches, plums, alders, and oaks. As the name suggests, symptoms include blistering and curling of the leaves. However, many insects can cause similar problems, so inspect leaves carefully and be sure to rule out insects before diagnosing these diseases.

Leaf Miners

Leaf Miners Feed Between the Upper and Lower Leaf Surfaces (Figure 44). If the leaf is held up to the light, one can see either the insect or frass in the damaged area (discolored or swollen leaf tissue area), i.e. boxwood, holly, birch, elm leaf miners.

Leaf and Stem “distortion”

Leaf and Stem “distortion” associated with off-color foliage generally indicates an infestation of aphids (distortion often confused with growth regulator injury)(Figure 45). There are many species of aphids, often associated with specific hosts such as rose aphid, black cherry aphid, leaf curl plum aphid, green apple aphid, etc. When aphids are curling the leaves, their remains are likely to be found within curled leaves for several weeks.

Figure 45. Leaf and Stem “distortion” associated with off-color foliage generally indicates an infestation of aphids

Needle Casts

Needle casts are simply foliar diseases in conifers. The needles may develop spots, blotches, or turn brown and die. Upon death, conifers shed or cast off the needles. Needle casts usually begin at the base of the tree and slowly spread up the tree, resulting in lower branch defoliation (Figure 46). The presence of fruiting bodies, like these pycnidia, is key diagnostic sign of needle cast disease (Figure 47).

Sooty Mold

Sooty mold, as the name suggests, appears as a fine coating of soot on the leaf surface, and is a commonly observed problem on the foliage of landscape plants. However, it is not a disease, but a group of fungi that live of the exudates (honeydew) produced by feeding aphids. (Figure 48 and Figure 49)

Leaf Galls

Many tree leaves commonly develop galls or growths on their upper or lower surfaces. Insects, not plant pathogens, cause most of these problems. Some leaf gall-causing diseases include azalea leaf gall, camellia leaf gall, and even some rust pathogens. Leaf galls on most other plants in Indiana are due to insects. To diagnose what type of gall you have, carefully crosssection the gall and examine it internally for the presence of any insect parts or frass (excrement). Common insect gall makers include aphids and their relatives, wasps, flies, rust mites, and beetles. Adult stages of insects must leave the swelling to create new galls. Many have complicated life cycles requiring alternate host.

Figure 50. Insect galls take many distinctive shapes and forms as shown: (TOP Left): Hedghog gall on red oak (cynipid wasp); (TOP Right): Wool sower gall on Oak (cynipid wasp); (MIDDLE Left): Poplar petiole gall (aphid) and (Right): Ash flower gall (rust mite); (BOTTOM Left): Cooley spruce gall adelgid damage on Douglas fir leaf; (BOTTOM Right): Cooley spruce gall adelgid gall formation on Spruce.

Bacterial Leaf Spots

Bacterial leaf spots are often initially confined between leaf veins resulting in discrete, angular spots. Chlorotic or red halos are frequently observed surrounding the lesion. As lesions coalesce, the damage may appear more like a blight as opposed to a discrete spot. (Figure 51)

Bacterial Leaf Scorch

Bacterial Leaf Scorch occurs when bacteria produce polysaccharides (sugars) that block the vascular water conducting tissue and cause yellowing, wilting, browning and dieback of leaves, stems and roots. Symptoms first appear on the leaves, despite the fact that it is the vascular tissue of the plant that is infected. (Figure 52)

Ringspots, Mottles and Mosaic

Foliar symptoms of virus disease can include green and yellow mottling, mosaic, or ringspots. Foliage may be mottled green and yellow without clear distinction. This is different than a mosaic, a discrete tiling of green and yellow areas over surface of leaf. Ringspot consists of target-like discolorations on the leaf.

Vein clearing

Vein clearing describes the translucent or transparent appearance of plant’s veins (Figure 54). This symptom can be mistaken for damage from herbicide, or can be confused with other nutrient deficiencies where leaf veins remain a darker green with surrounding chlorotic tissue.

Rugosity

Rugosity describe the puckering or quilting of leaves, and the rosettes that sometimes occur can be the result of virus infection, herbicide damage, or a normal horticultural selection, as in the case of this Poinsettia (Figure 55).

Leaf curling or Puckering

More severe toxemias such as tissue malformations develop when toxic saliva causes the leaf to curl and pucker around the insect. Severe aphid infestations may cause this type of damage. “Leaf cupping” on Boxwood is caused by Boxwood Psyllids

Systemic Toxemia

In some cases the toxic effects from toxicogenic insect feeding spread throughout the plant resulting in reduced growth and chlorosis. Psyllid yellows of potatoes and tomatoes and scale and mealy bug infestations may cause systemic toxemia.

Distortions

Distortions of leaves and flowers can result from herbicide damage, virus or phytoplasma (a type of wall-less bacterium) infection (see Chapter 9).

Carefully examine infected plants to see if the damage affects plants of a single age (abiotic), or to determine if the symptoms are spreading (biotic). If biotic causes are suspected, a laboratory diagnosis will most likely be needed to conclusively identify the causal agent as neither phytoplasma nor viruses produce visible signs

Necrotic areas or lesions

Being obligate parasites, viruses require the survival of their host plant for their own procreation. Hence, viruses rarely cause death. Necrosis that does occur is usually confined to discrete areas of the plant; necrosis rarely occurs to such an extent that the entire plant is killed. (Figure 57)

Note about viral diseases of plants

Many symptoms of viral infection can be readily confused with symptoms caused by nutritional disorders, spray injury, feeding damage by mites or insects, or “unusual” selections of horticultural plants, like Poinsettia ‘Avant Garde’ in Figure 58.

Foliar nematodes

Foliar nematodes feed inside leaves between major veins and usually aren’t recognized until tissue turns yellow and rapidly dies within veins. This pattern is netlike in the case of dicots (Figure 59 Left), but follows the veins in the case of monocots like hosta (Figure 59 Right), or daylily.

Figure 59. Foliar nematodes feeding pattern is netlike in the case of dicots (Figure 59 Left), but follows the veins in the case of monocots like hosta (Figure 59 Right), or daylily.

Stem Diseases

Wilt

Wilt symptoms result from many causes: Drought, flooding, damage to the plant stem, colonization of the vascular system, or may be a slow and subtle dieback and decline from root problems. Keep in mind that wilt describes the inability a plant to transport water and photosynthates, and can be due to a variety of causes. Furthermore, wilt disease exacerbates the symptoms of drought as the plant’s roots are compromised. Common wilt diseases include Dutch elm disease, oak wilt, fusarium wilt, verticillium wilt, and pine wilt.

Figure 60. Wilt due to (TOP Left): daisies require a lot of water; (TOP Right): a distal canker on the hydrangea stem. Wilt due to (BOTTOM Left) Ralstonia solanacearum of annual geranium; (BOTTOM Right): an insect borer of sunflower.

Damaged Twigs (Twig Splitting)

Damage resembling a split made by some sharp instrument is due to egg laying (oviposition) by sucking insects such as tree hoppers and cicadas. Splitting of the branch is often enough to kill the end of the branch, i.e. cicada.

Petiole and Leaf Stalk Borers

Petiole and Leaf Stalk Borers burrow into the petiole near the blade or near the base of the leaf. Tissues are weakened and leaf falls in early summer. Sectioning petiole reveals insect-larva of small moth or sawfly larva, i.e. maple petiole borer (Figure 61 Top).

The canes of Roses and Raspberries are prone to attack by cane borers, which can enter via pruning cuts and consume the pithy center of the cane (Figure 61 Bottom).

Cankers

Canker is a term that describes a lesion that results in the death of a localized area. Cankers can appear on the branches, twigs, or trunk of broadleaved plants. Cankers can result from mechanical damage (cars, weed whips, and lawn mowers), environmental conditions (frost cracks, sunscald, etc.), insects, or pathogens (fungi and bacteria). Many opportunistic canker pathogens require mechanical damage or injury to infect and invade the plant. These wounds provide an entry to pathogens, predisposing them to disease.

Figure 62. (TOP Left): Cankers often infect via pruning injury. (TOP Right): Annual canker on rhododendron. (BOTTOM Left): Diffuse canker that will eventually kill this plant; (BOTTOM Right); Scattered cytospora cankers on blue spruce – a commonly encountered spruce problem in Indiana.

Twig Girdlers and Pruners

Figure 63. Twig girdlers chew around twigs (TOP Left), while twig pruners feed as larvae from the inside working outward (BOTTOM Left). Black vine weevil larvae (Right) chew on stems of plants at the soil line and feed on leaves as adults.

Borers

Borers feed under the bark in the cambium tissue or in the solid wood or xylem tissue. The first symptoms of damage are often recognized by a general decline of the plant or a specific branch.

Figure 64. Close examination will often reveal the presence of holes in the bark (TOP Left), accumulation of frass or sawdust-like material or pitch (TOP Right). Excavation of the area around the exit would often reveals galleries, like those found due to emerald ash borer (BOTTOM Left) or smaller European elm bark beetle galleries (BOTTOM Right).

Shoot Feeders

Adults of these insects can lay eggs in twigs. Larvae will tunnel into the shoot and cause curling. The white pine weevil, usually found in “leader growth,” is a pest of white pine that falls neatly into this category. (Figure 65 and Figure 66)

Figure 66. Shoot feeders can sometimes enter from the ground up as with these fungus gnats on this heavily infested poinsettia.

Oviposition Injury

Oviposition injury on twigs is distinct from shoot feeders in that the damage is caused when the eggs are laid into the twig (Figure 66). Periodical cicadas lay eggs into the twigs and stems which may ultimately kill those twigs and stems (Figure 67).

Figure 67. Periodical cicadas lay eggs into the twigs and stems which may ultimately kill those twigs and stems.

Gall

Crown gall, caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Figure 68), often infects at the base of the plant where the roots meet the stem, but can spread systemically throughout the plant. Other bacterial galls produce smaller galls, commonly in honeylocust in the Midwest.

Note: Bacterial disease problems are often difficult to distinguish from fungal pathogens. Although some symptoms are distinctive, care must be taken not to diagnose the problem on symptoms alone.

Fungal galls generally appear on the stems and canopy of the affected woody plant. Black knot is a common gall of ornamental cherry and plum (Figure 69). Most other fungal galls are caused by rust pathogens. Rust galls result when rust fungi infect susceptible host plants. Infection can result in round to cylindrical galls. Cedar-apple rust is perhaps the most common, but western pine gall rust also regularly infects Scot’s pine. It is important to note that most foliar galls are caused by insects, with a few exceptions.

Figure 69. (TOP Left): Black Knot on ornamental Plum; (TOP Right): Juniper rust (BOTTOM Left): Rust on Ash; (BOTTOM Right): Eastern gall rust on Pine.

Blight

Blight refers to a specific symptom affecting a plant in response to infection by a pathogenic fungus or bacterium. Often included with anthracnose, and canker pathogens, the symptom of blight describes the rapid and complete yellowing, browning, and then death of plant tissues. Blight symptoms may first appear on leaves, twigs, branches, or even flowers. Symptoms of blight often appear first on leaves or needles; these lesions continue to grow and rapidly engulf surrounding tissue, or work through the petiole or fascicle, into the branch of the affected woody plant. Cankers may or may not develop.

Figure 70. Fire blight is a devastating bacterial disease of rosaceous plants, capable of killing young apple and pear trees.

Figure 72. Botrytis blight has a broad host range, and can infect both woody and herbaceous plants, as evidenced by these infected annual geranium flowers.

Diagnosing Root Problems

Insects are rarely the cause of root system failure in the Midwest. A primary biotic cause of poor plant health in ornamental plants is root system diseases; these problems are also the most frequently underdiagnosed. This lack of diagnosis is most often due to the slow development of disease symptoms, coupled with the vagueness of the condition: Slow(er) growth, nitrogen or other nutrient deficiency, decline in crown, smaller leaves that may or may not be chlorotic, heavier seed crops (in landscape plants), and the simple fact the roots are not readily observable. Symptoms often resemble, or mimic wilt. Often, secondary insects and opportunistic fungi attack these plants, and are blamed for the overall poor health. Many soil-borne pathogens are anaerobic and prosper in poorly-drained soils.

Excavation of the root and crown of these plants may reveal dead feeder roots and dark streaks up stem wood. Other root rots, or severe root rot may result and the root cortex may easily slough off. Most root rots require laboratory diagnosis to conclusively identify the pathogen.

ROOT FEEDERS

Root Feeders: larval stages of weevils, beetles and moths cause general decline of plant, chewed areas of roots, i.e. sod webworm, Japanese beetle, root weevils.

ROOT, STEM, BRANCH FEEDERS

General Decline of Entire Plant or Section of a Plant as indicated by poor color, reduced growth, dieback. Scales, mealybugs, pine needle scale.

NEMATODES

Nematodes are microscopic roundworms (unrelated to earthworms) that damage plant tissues when feeding on them. There are many different types of nematodes that infect the root. Symptoms often appear as moisture and/or nutrient stress symptoms. Reduced growth, stunting and a failure to thrive are common symptoms. The most common landscape nematodes include:

Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.)

Cause galls to develop as a result of their feeding. Oval to elongate galls ranging from 1/8” to 1” in diameter. These galls, or knots can cause dieback or death infected plants. Early infections often cause wilting in the infected plant, with the plant recovering at night. May be confused with Rhizobium nodules (nitrogen fixing) on roots.

Lesion and Dagger Nematodes

The root lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.) and dagger nematode (Xiphenema spp) travel from plant to plant, feeding and killing root tissues. In addition to the damage caused by the nematodes, the infection courts they create predispose plants to infection from soilborne pathogens like Verticillium, Fusarium, and other root rots. Some of these nematodes can also vector viruses that cause plant disease. Feeding results in small dark lesions on fibrous roots resulting in stunting. Moves through root tissues.

Stubby Root Nematode (Trichodurus spp.)

Feeding damage results in stubby roots as feeding on root tips and young root causes a reduction in the length of the small fibrous roots. This nematode also vectors tobacco rattle virus, a common landscape virus with a host range of several hundred plants (See Figure 53).

Figure 74. (LEFT): Root knot nematode damage results in large galls (Photo by TAMU). (RIGHT): Lesion nematode damage results in a reduction of root growth (Photo by OrSU)

DECLINES

Decline Complexes: for Sudden decline, usually an abiotic disorder, (See Sudden Decline above in Determining the nature of the problem section)

Gradual decline

Gradual decline of entire plant can be a result of poor site, Improper planting depth, injury, or infection by any number of root rot pathogens. This often requires teasing apart underlying abiotic issues, like poor site, coupled with biotic problems, like insects and disease. These are some of the most difficult diseases to diagnose, and often, by the time the problem has been identified, it is too late too manage, too. Therefore, it is important to stay on top of problems as they develop, through a regular scouting program.

A Final Word

The Purdue Plant Doctor (https://purdueplantdoctor.com/index.html) will assist you in diagnosing the most common problems you encounter in Indiana. Our series of short videos on YouTube can provide tips on using the site to manage common pests. If you have identified the host, and narrowed down the probable cause through a systematic approach that evaluates the impact of biotic and abiotic problems, and still aren’t sure of what the problem is, you may need assistance to conclusively identify the specific responsible organism or abiotic factor. Laboratory analyses and examination may be required to further narrow the range of probable causes. Don’t fret! We rely on the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab at http://www.ppdl.purdue.edu/ppdl/index.html as well, for their excellent efforts in diagnosing difficult plant health problems.