PART ONE: Biology and Management of Plant Diseases – Learning Objectives

From reading and studying this section, you should be able to:

- Describe seven types of plant pathogens.

- Discuss basic plant pathogen management tactics.

- Understand how to use fungicides effectively.

This chapter serves as an introduction to plant pathogens that commonly infect ornamental plants in Indiana, and how to understand plant disease using the disease triangle. Diagnosis of the most common plant disease problems is covered in Chapter Five.

After a problem is identified as a plant disease, the disease triangle provides a framework for understanding, preventing, and managing the plant disease problem. The chapter concludes with an overview of how to effectively use fungicides as part of an integrated program of plant disease management.

WHAT IS PLANT DISEASE?

Plant disease is defined as any problem that damages the appearance or yield in crop. Plant disease is often broken into two categories:

- Abiotic: These are disorders, including, but not limited to misapplication of pesticides, soil issues, or weather-related injury, and

- Biotic: Limited to living organisms (and viruses) that cause disease and are referred to as plant pathogens.

WHAT ARE PLANT PATHOGENS?

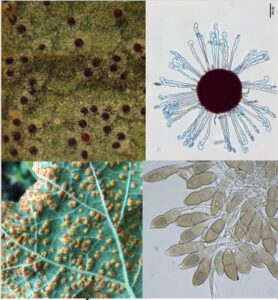

FUNGI

Fungi are the most frequently encountered group of plant pathogens, with most plant pathogenic fungi (plural of fungus) belonging to the division Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota. These are also called “true fungi”. These fungi reproduce by spores that are usually contained in fruiting bodies. Some fungal fruiting bodies are easily visible, like the orange galls of a juniper rust (Fig. 2), or the mushrooms produced by the root rot fungus Armillaria (the spores are on produced by the gills), Other fungi, usually ascomycetes, produce tiny pustules within the infected needle, leaf, branch or root, and often require a hand lens or a microscope to observe. The spores are produced by these pustules, like Rhizosphaera needle cast (Fig. 3).

Regardless of how the spores are produced, they all germinate, and upon germination, enter the host plant through natural openings, wounds, forced (mechanical) entry, or through the use of chemicals (enzymes) that digest the cell wall. After successful infection, the fungus invades the host tissue, causing damage by producing substances chemicals (toxins, enzymes, proteins, hormones) that change or destroy plant tissues. A video of this process can be seen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGwbUzPX4jE

Common fungal diseases include anthracnose, blight, damping- off, leaf spot, powdery mildew, root and crown rots, rust, smut, and vascular wilts.

Figure 3. Black erumpent pustules emerging from the Rhizosphaera infected needle on top. Bands of healthy white stomata are seen below

Figure 4. Powdery mildew pustules include chasmothecia that look like koosh balls (top); Rust pustules on hollyhock (lower left) produce hundreds of thousands of spore per leaf (lower right).

WATER-MOLDS- OOMYCOTA

Historically, this group was included with the Fungi, even though certain characteristics (e.g., zoospores that swim, a cell wall composed of cellulose instead of chitin) indicated that they were, in fact, something quite different. This is a very important point because many of the ‘fungicides’ most effective to control these diseases will not work on the ‘true fungi’. Commonly referred to as Oomycetes, ‘water molds’, pseudofungi, or lower fungi, this group includes some of the most destructive plant pathogens including Phytophthora, Pythium, and the downy mildews. Despite not being closely related to the fungi, the oomycetes have developed very similar infection strategies, including spores that germinate and cause infection. They are some of the most destructive plant pathogens in ornamental and agricultural crops (Fig. 5).

BACTERIA

Bacteria are microscopic, single-celled microorganisms that are very different than plants or animals (Fig 6). This difference is why antibiotics kill bacteria, but don’t (generally) harm animals. Bacteria enter through wounds, stomata or other natural openings where they produce chemicals (toxins, cell-wall degrading enzymes, hormones, or slime that blocks water transporting vessels) that destroy plant tissue or cause abnormal growth.

Figure 6. An image of fire blight bacterium that uses whip-like flagella to propel itself over and in plants. (Image source unknown).

Common bacterial diseases in Indiana include fire blight (Fig. 7), leaf spots, crown gall, and bacterial wilts.

PHYTOPLASMAS

Phytoplasma are similar to bacteria but lack cell walls. This means instead of being a set shape, like a rod, or round, phytoplasmas are like microscopic blobs. This makes growing, studying, and detecting them very difficult! Phytoplasmas are most often transmitted by sap- sucking insects like leaf hoppers and glassy- winged sharpshooters. These phloem-feeding insects introduce the phytoplasma to the phloem where it reproduces. Many plant health problems previously considered to be viruses, namely ‘yellows’ or ‘phloem necrosis’ diseases, are caused by phytoplasmas. Aster yellows, infecting many common perennials, is a common landscape problem caused by phytoplasmas.

Figure 8. Aster yellows symptoms on purple coneflower. Care must be taken to rule out herbicide or broad mites when diagnosing this problem.

VIRUSES

Viruses are submicroscopic particles (meaning you can’t see them even with a microscope!). To infect, a vector must transmit the plant virus to the uninfected plant. Vectors are usually insects (for example aphids, whiteflies, thrips), but other organisms can serve as vectors, as well. Humans, particularly smokers, can vector tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) simply by smoking and later handling plants. Symptoms of virus infection include mosaic, mottling, spotting or chlorosis of foliage; abnormal growth that may be mistaken for herbicide damage; thickened leaves, or deformity. Host range can be specific, as in the case of hosta virus X (HVX) or broad: Impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV), cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), tobacco rattle virus (TRV, Fig. 9) and tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) have been reported to infect hundreds of plant species each.

Figure 9. Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) on hosta.TRV has been reported to infect several hundred species of plants.

Managing viruses is limited to removing and destroying infected plants, or managing the vector, when feasible.

NEMATODES

Nematodes are small, multicellular worm-like (but unrelated) creatures (Fig. 10). Many live freely in the soil, but there are some species that parasitize plant roots or foliage.

Figure 10. Lesion nematode. Arrow points to the stylet that identifies this as a parasitic nematode. Most nematodes are free-living and feed on bacteria.

Plant pathogenic nematodes suck out liquid nutrients and inject damaging materials into plants with their stylet. In the process, they injure plant cells or change normal plant growth processes. Symptoms of root nematodes include swelling of stems or roots, irregular root branching, mid-day wilting with recovery of the plant at night, and galls on roots. Symptoms of foliar nematode can be seen in Fig. 11.

Nematodes can vector viruses and fungi into plants. Other common nematodes of landscape plants include foliar nematode (Aphelenchoides spp.), root knot nematode (Meloidygyne spp.), pine-wilt nematode (Bursephalenchus spp.) and dagger nematode (Pratylenchus spp.).

PARASITIC PLANTS

A parasitic plant is one that derives some or all of its sustenance from another plant. Parasitic plants have a modified root, the haustorium, which penetrates the host plant and connects to the vascular tissue. Common parasitic plants encountered in the Indiana landscape include dodder (Fig. 12). The wildflower, Indian-paintbrush (Castilleja spp.) is hemi-parasitic on roots of grasses and forbs. Leafy mistletoe (Phoradendron spp.) is slowly working its way in from Kentucky and may become established in southern Indiana.

Figure 12. Dodder, a parasitic plant, infecting a mum. Unlike other plant pathogens, dodder is best managed using pre-emergent herbicides.

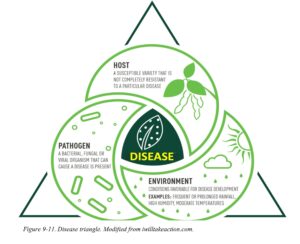

THE DISEASE TRIANGLE

The pathogens listed above are only one part in what is referred to as the disease triangle (Fig. 13). Three major factors contribute to the development of a plant disease: a susceptible host, a virulent pathogen, and a favorable environment. A plant disease results when these three factors come together. If one or more of these factors do not occur (or can be stopped!), then the disease does not occur.

Just as our genetic makeup determines if we will be tall or short, brown eyed or blue eyed, the genetic makeup of the plant determines whether it is susceptible to disease. Some plants are more resistant to certain pathogens (see Resistance) whereas others are extremely susceptible. The plant’s developmental stage also may influence disease development: older plants are often less susceptible to damping-off or foliar pathogens, but are more susceptible to opportunistic pathogens, and powdery mildews. In addition to host resistance and susceptibility, pathogens differ in their ability to infect (pathogenicity), how aggressively they infect (virulence). Some pathogens are simply more aggressive than others. Finally, the environment affects both host and pathogen: Drought stressed plant are often more susceptible to disease, however, drought often reduces the spread of many pathogens. Conversely, cool, moist conditions encourage the growth of both plants and many plant pathogens.

THE DISEASE CYCLE

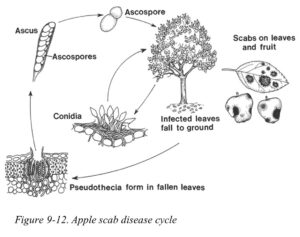

The interaction between host, pathogen, and environment that defines the disease triangle determines the development of disease. Understanding this chain of events allows the practitioner to identify the weakest link and develop the best management options to break the disease cycle (Fig. 14)

Some diseases are characterized by a single cycle during the year (e.g., the juniper rusts), whereas other diseases continually produce new inoculum, repeating the cycle numerous times over a single growing season (e.g., apple scab, powdery mildews, hollyhock rust, fire blight, Phytophthora, etc.). This means some disease may be managed by one or two well-timed applications of fungicides, whereas others may need fungicide application all season long to look their best!

DISEASE MANAGEMENT

The basic principles of plant disease management are:

- Prevention

- Exclusion

- Eradication

- Protection

PREVENTION

To state that ‘preventing plant diseases is the best management practice’ may be an expression of the obvious, but it bears repeating. Healthy plants are better able to resist diseases; choosing the right plant for the site avoids future disease problems. This is discussed in Chapter 1.

Hardiness

Before buying any plant, determine if it is truly zone hardy. Many perennials are only borderline hardy for the extremes of their hardiness range—Evaluate the claims of several different nurseries before investing in plants that are unreliably perennials, or worse yet, annual in your climate! This is especially true when trying new species—many popular new releases undergo a shrinking of zone hardiness several years after release. Consider the type of plant being installed: the impact of a losing three coreopsis may be worth the risk; the loss of three trees 15 years after installation is probably not.

Site Characteristics

Instead of picking plants, and then deciding where to plant them, objectively evaluate your site, and then compare them to the list of plant requirements. Yes, even plants have requirements, and not meeting them (at least part way) is the surest way to predispose them to disease. Plant requirements concern light, drainage, and fertility. Then, match your plants to your site. No one would plant a cactus in a rain garden! Then why plant Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium sp.) in dry sand—unless you are prepared to irrigate.

Light

To photosynthesize, plants require light. Light intensity and duration are important for both flowering, aesthetics, and ornamental plant health health. For example, hosta are very tough, disease resistant plants, unless put in full sun, where they become bleached, scorched, and predisposed to leaf spots and other diseases. When evaluating light requirements, remember:

- Sun: 6 hours or more of full sunlight

- Part shade: 1/2 day of sun (either morning or afternoon). This also refers to lightly filtered sun through tree branches like honey-locust, mimosa, or

- Shade: woodlands; areas with minimal direct sun; exposure north-facing beds shaded by structures; areas receiving less than 4 hours of sunlight per

Improper light levels can cause plant stress: low light levels cause plants to grow leggy (etiolate), reduces flowering, and can result in poor fruit set and quality for sun-loving plants. For shade-loving plants, high light can scorch or burn leaves, providing an infection court for opportunistic pathogens.

Checking Planting Depth

Follow the planting depth recommended for each species– Planting plants too deeply predisposes them to stem girdling roots, root girdling roots, and crown rot. Improper planting can result in a failure to flower. Planting too shallowly can cause plants perish during winter.

Adequately Spacing Plants

Crowded plants prevent good air movement, which promotes foliar diseases. Close spacing also causes plants to compete against each other for sunlight and nutrients. Many hedges and windbreaks, upon reaching optimal spacing, often develop disease.

Proper Mulching

Mulch is much touted, as it minimizes weeds, maintains soil moisture, and moderates soil temperature. However, there is too much of a good thing, and excessive mulch can prevent good root establishment and development, serve as a site for rodents, and contribute to crown rot.

Appropriate Watering

Most perennials require approximately one inch of water per week depending on soil type. Sandy soil can tolerate a good soaking, whereas one inch of rain per week should be divided into half inch increments on heavy clay. Water is for the roots–avoid overhead irrigation, and when watering, water plants in the morning so foliage can dry before nighttime.

Adequately Fertilizing

Fertilizer should only be applied when nutrient deficiencies are noted, such as yellowing (chlorosis), abnormal red coloration, or stunting. Too much fertilizer predisposes plants to disease and prevents many flowering plants from flowering. Once a year in the spring is sufficient for most perennials; most annuals are heavy feeders that require multiple applications of fertilizer per season.

Winter Protection

Winter protection can protect plants from heaving during freeze-thaw cycles and are applied after the ground has frozen. This type of mulch should be removed in the spring to prevent new growth from rotting.

RESISTANCE

The implementation of plant disease resistance is considered one of the most efficient and effective methods to control plant diseases and has served as a cornerstone of agriculture (Fig. 15). However, its use in the ornamental industry is only beginning to be realized (Rose ‘Knock Out’, Phlox ‘David’ are two examples). Consumers and producers have been slow to adopt host resistance as a strategy for IPM in commercial production unless disease severity reaches a critical threshold, and other management tools are ineffective. Part of this lack of adoption may be due to the term ‘resistance’ as it is sometimes used interchangeably with “immunity,” or “tolerance.” All of these terms describe a plant’s ability to minimize disease, and in some instances, even abiotic disorders! Immunity describes the inability of a plant to ever become infected by a given pathogen (i.e., oaks cannot be infected with Dutch elm disease or fire blight). Unfortunately, resistant cultivars can still become diseased in many instances, but rarely as much as other cultivars or species. Tolerance is term more often used in agronomic crops and describes a plant that supports some disease, but isn’t overly debilitated by the level tolerated.

One problem with resistance is that it can fail, or “break down” over time. This is an unfortunate term, as the resistance hasn’t changed—however, the insect or pathogen population has adapted and is now able to infect a once-resistant host. Notable resistance breakdowns in ornamental plants include the crabapple ‘Adams,’ Rose ‘Hansa’, and the infection of the Dutch elm disease resistant elm ‘Cathedral’ or ‘Princeton’ as it ages, and under high disease pressures.

EXCLUSION

Another principle to prevent plant disease is exclusion, a fancy way of saying “Keep it out!”. This prevents the introduction of a pathogen into a planting and includes quarantines, inspections, and certification. Furthermore, natural barrierlike mountains, deserts, and oceans prevent the natural spread of pathogens between discrete geographic areas.

Other forms of exclusion include:

- The use of culture indexed stock (specially propagated, virus-free plants) or pathogen free seed prevents the potential introduction of diseased plants.

- The cleaning and/or sterilization of equipment used for pruning or digging between sites to prevent the introduction of pathogens.

ERADICATION

As a tactic, eradication focuses on eliminating a pathogen after it is introduced into an area prior to its establishment and dissemination. Eradication can focus on a single planting plant, such as the removal of a fire blight infected limb, a large planting bed, to large geographical areas, as is the ongoing situation with the Ramorum blight pathogen Phytophthora ramorum, in the Pacific Northwest.

Other methods of eradication include:

- Rotation, which is commonly done in agricultural fields but can be done with beds of annuals and perennials. Changing beds from host plants to non-host plants over the course of several years can reduce inoculum. Examples of effective use for this strategy includes not planting Fusarium susceptible snapdragons for several years, and instead, planting Hollyhocks that are not susceptible to this form of wilt.

- Sanitation consists of removing infected plants promptly to minimize disease. After the first frost, cut plants back completely and dispose of infected tissue. Regular removal of fading flowers (deadheading), or infected leaves during the growing season minimizes the buildup and spread of disease-causing organisms. If foliar disease like powdery mildew, or leaf spot occurs early in the season after a plant has flowered, cut the infected plant severely–It will produce a new flush of foliage, and possibly another crop of blooms. Flail mowing of leaf material results in more decomposable leaves. Faster rates of decomposition prevent the development of fruit body formation, preventing disease development. Finally, remove and destroy debris and soil that can harbor pathogens. Some pathogens, like Verticillium, can persist in plant debris, or even weeds. Removing debris and weeds is essential in eradication of this pathogen.

- Heat treatment is used on high-value plants (fruit plants, roses, perennials) to eradicate viruses and other pathogens from culture-indexed plants. This is done in the greenhouse and nursery, not in the landscape.

These petunias (Fig. 17), showing symptoms of iron chlorosis, are actually infected with Phytophthora. Notice how the dusty miller is not affected. Replanting petunias in this location will likely result in the same outcome.

Figure 17. Rotation is a cornerstone of landscape disease management, particularly when dealing with root rots.

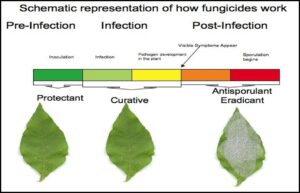

Historically, some fungicides were described as ‘eradicants’. These chemicals provide “kick back” and eradicate pathogens from infected plants. Over-use of these chemicals has rendered them less effective for this purpose, and few of these actually work that way today.

PROTECTION

The other principles (prevention, exclusion, and eradication) describe tactics used to prevent, reduce, suppress, or eliminate plant disease. Protection describes the successful implementation of all these tactics to maintain plant health. Ultimately, protection involves ‘shielding’ the susceptible plant from inevitable infection by the pathogen. Even resistant plants can and do get disease and may require protection from severe outbreaks of the diseases they are resistant to, or to other diseases. Most often, a chemical barrier (pesticide) is applied to the susceptible plant, but physical barriers, and biological control can be employed, too. It does not include the cultural characteristics involved (see Prevention). Plant protection includes specific acts to prevent imminent disease and that infection and disease will occur without the intervention of protective measures. This is distinct from prevention, which seeks to avoid subjecting the plant to stress, or possible infection by improving plant health, minimizing the likelihood of disease by creating pathogen unfavorable situations, or avoids problems by changing planting dates or depths.

Protection, like prevention, does require a certain degree of proactiveness in that both tactics require the practitioner to manage a healthy plant before problems develop. Furthermore, chemical protection works best when applied prior to the development of the inevitable plant damage. Few pesticides eradicate the already established pathogen, and none can repair or “heal” plant damage once it has occurred.

Chemical protection is one of the most widely used means of control. Fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides are the primary chemical protectants (pesticides) used to manage plants. A fungicide is a type of pesticide that inhibits or kills the fungus causing the disease. Proper timing, coverage, and selection of fungicides are also needed, meaning it is necessary to know the biology and disease cycle of the pathogen. Fungicides can be very specific to certain types of fungi (Basidiomycetes, Ascomycetes, or Oomycetes); thus, proper disease diagnosis and understanding is essential to developing a successful plant health strategy. There are no silver bullets in managing plant disease because there are so many different types of pathogens.

Physical protection of plants involves the use of non-chemical barriers (Fig 18.). Bagging fruit, covering plants in floating row cover, the incorporation of reflective ground covers all work to protect plants from attack by pathogens, or by the insects that vector them. In the landscape, the use of these measures is limited.

Figure 18. Protecting spruce from winter injury may look ridiculous, but is effective when weather is extremely cold, sunny and dry (or frozen).

PROTECTION FOR HIGH VALUE PLANTS

On high value plants, the therapeutic use of chemicals or other treatments is an option of increasing importance in the landscape. Therapeutic application of fungicides to cure the already infected plants is an approach mostly limited to high value trees and has been successfully employed to treat Dutch elm disease, oak wilt (Fig. 19), sudden oak death and emerald ash borer. In all cases, certain limitations apply, and only early infections/infestations can be managed or prevented.

Historically, many systemic fungicides (oxathiins, benzimidazoles, and sterol-inhibitors) have enabled growers to treat many plants after an infection has begun. These chemicals are absorbed by the plant and translocated throughout the plant, restricting the development of pathogens. However, the increased frequency of resistance has resulted in a loss of these fungicides. Therefore, the use of these fungicides therapeutically is not recommended, as it increases the risk of fungicide resistance.

PART TWO: Effective Fungicide Use – Learning Objectives

From reading and studying this section, you should be able to:

- Describe what fungicides are and what they do

- Explain the process to effectively using fungicides

- Discuss the different formulations of fungicides and how formulation can impact delivery

- List and explain different modes of fungicide action

- Identify the key components needed for successful fungicide rotations

- Give specific examples how to rotate fungicides to properly manage diseases

- Be familiar with the fungicides and the terminology related to fungicide use

| Video | Link |

| Fungicides 1. What are Fungicides and How do They Work? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNiqROUtpgo |

| Fungicide No. 2: How Do Fungi Attack Plants? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGwbUzPX4jE |

| Fungicide 3: Why Use Fungicides? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVas6juNnfc |

| Fungicide No. 4: Why Didn’t My Fungicide Work? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M8-1xfo243Y |

Introduction

Many people assume that if a chemical is used to control a disease-causing agent, it will cure the plant, no matter when and how they use it. Unfortunately, most fungicides prevent infection from occurring, and very few actually “cure” diseases. Furthermore, fungicides are only effective when the problem is fungal. Many other organisms (insects, bacteria, viruses, nematode, etc.) and abiotic (heat, cold, pH, etc.) factors can negatively impact plants. Fungicides work best by preventing fungal disease from becoming established in the first place. In this way, they act more like a vaccine, than an antibiotic or other drug. Unfortunately, most people (understandably) approach plant health problems like human or pet health problems and expect a set treatment to “cure” the disease after the problem has occurred. This doesn’t mean that fungicides don’t work—far from it. A properly chosen, and properly applied fungicide is an important component of any disease management program. To use them most effectively, fungicide use should be integrated with the proper cultural practices, an understanding of pathogen, and disease biology.

Most fungicides, particularly natural or organic fungicides, protect plants by covering their surface and preventing infection from occurring so long as that protective coating isn’t washed off or outgrown. Other fungicides are systemic, and are active within the plant, preventing disease from becoming established. Using a fungicide effectively requires a solid strategy of integrated plant management. Of course, the backbone of integrated plant management includes carefully matching the plant to the soil type, sunlight levels and watering conditions; proper sanitation; appropriate fertilization and pruning, when necessary. These strategies work together to prevent disease problems from developing in the first place. By using an integrated approach, fungicide use is minimized, as is the risk of fungicide resistance development. Simply stated: The less frequently fungicides are needed to be used, the less frequently resistance can develop.

Proper fungicide use relies upon the correct diagnosis.

Perhaps the most important, and most often overlooked aspect of plant health management is proper diagnosis. Too often, practitioners think they know what the problem is, and did not actually make a formal diagnosis. Prior to applying any chemical, make certain of your diagnosis. Fungicides are only effective when the disease-causing agent is fungal! If you are certain of your diagnosis, proceed to the next step of identifying which pesticide is best for the problem you wish to manage. The most effective fungicides are fairly specific in their use– fungicides to control Phytophthora or Pythium root rot aren’t going to work for Rhizoctonia, and vice versa. Some fungicides may only control Phytophthora and downy mildews, and not work on Pythium, another oomycete pathogen. Throughout this chapter, we’ll use Phytophthora as an example.

Figure 20. You have identified and diagnosed two distinct problems, Phytophthora root rot and Phytophthora aerial blight. Which fungicide, which formulation, and what rotation, if any, is needed?

Selecting the appropriate chemical and formulation.

This means reading the label. Even after a fungicide has been recommended by a reputable source, you should ALWAYS read the label. This isn’t just a good idea, but it is the law.

Although many chemicals, particularly the strobilurins, have activity against a wide range of pathogens, most do not. Often the best control can be obtained with a specific fungicide, instead of a fungicide with a broad range of activity. This may require some research (label reading, reputable industry sources, extension websites) on your part to identify which fungicide works best. An excellent website to consult is the Turf and Ornamental BlueBook Website at: https://www.cdms.net/LabelsMsds/LMDefault.aspx .

Remember to determine if the plant you wish to treat is labeled and that no contraindications exist. Certain plants develop phytotoxic reactions to some fungicides, and these reactions are almost always noted on the fungicide label. Make sure you can follow the recommended instructions as to the number of applications, or the addition of any adjuvants. Spending a few hours of your time is not going to change the outcome of your disease problem. However, not spending that time can cost you your entire crop!

After identifying the fungicide that you wish to use for disease management, consider which formulation that best serves your purpose. Fungicides are formulated in different ways, to increase efficacy and safety. Some of the most common formulations are:

- G(R)-Granular

- DF-Dry Flowable

- WG-Wettable Granule

- WP-Wettable Powder

- EC-Emulsifiable Concentrate

One fungicide labeled for the control of Phytophthora is Subdue Maxx. Subdue Maxx comes in two formulations.

- Subdue GR is a granular formulation, can be applied to the surface or incorporated into the growing medium. This would be very useful for the root rot when used to prevent disease, but not particularly so for the aerial blight, as it will take some time for the xylem-mobile Subdue to make it to the stem canker, and the Subdue would be taken up by the entire plant, not just the blighted lesions, essentially diluting the impact of your application. Applying granules to the leaf surface will result on them ending up on top of the soil, This has the lowest amount of active ingredient of all three formulations.

- Subdue Maxx recently updated its 12-page label, and specifies different rates for different crops, and whether they are grown in a greenhouse, nursery or landscape. The label clarifies that crops like azalea, which are very susceptible to Phytophthora root rot may receive a higher rate than other ornamentals. The label also states that it can be applied as a soil drench (controlling the root rot) or as a foliar application. This is the one fungicide and formulation that serves both needs, protecting foliar blight and root rot.

Applying the chemical at the right time.

By the time the symptoms are severe, it is too late to begin spraying. For our example, dead and symptomatic plants should be removed and destroyed. The goal is to treat plants that are showing symptoms to protect them from infection.

Remember: Fungicides, in general, protect new growth. No fungicide in the world is going to “cure” or “heal” any already present lesions, although the DMI fungicides (containing the active ingredients of triademefon, myclobutanil, tebuconazole and propiconazole) can “burn out” existing infection. Ideally, the first fungicide application should be made at a time just before the pathogen contacts the plant surface. Unfortunately, this requires an understanding of the pathogen life cycle (Fig. 14 is an example for apple scab. Phytophthora in the Landscape, available at https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/BP/BP-215-W.pdf has a lifecycle and more specific recommendations), and the environmental conditions that trigger the release and spread of the pathogen. Fungicides protect new growth, and stop the spread of the disease—nothing more, nothing less. When applying a fungicide, recognize temperature limitations (rain, windy, too hot, or too cold) and apply during acceptable weather conditions. When applying any chemical, be sure to protect yourself appropriately.

Figure 21. Incorrect timing of fungicides is a leading cause of disease control failure. If you wait to apply fungicides until the symptom are severe it will be too late!

Applying the appropriate amount.

Make sure to follow the labeled rate. Many people believe if a little is good, a lot is better! Nothing could be further from the truth, or more toxic to your plant. Most fungicides have gone through numerous trials to identify optimal amounts. Excessive amounts can result in phytotoxicity (plant damage). This is no different than an “overdose” in a human: Two aspirin can control a headache; 50 aspirin can kill you. Making up the right amount in the beginning is helpful as you don’t feel you are wasting fungicide—or money.

Overdosing isn’t the only problem with fungicides. A much larger problem lies in under-dosing or cutting labeled rates. Less than labeled amounts usually fail to control the disease problem and can create additional problems in the form of fungicide-resistant pathogens. Remember that the label is the law, and to follow it to ensure that a treatment has the greatest likelihood of being effective.

Adequately covering the plant.

Fungicides applied to the foliage act as a chemical barrier on the plant surface, preventing the pathogen from infecting the treated plant. To be effective, coverage must be complete. The effectiveness of the barrier depends upon how well the plant surface was covered, and how well the spray adheres to the plant. Some plants, particularly those with very hairy or waxy foliage, are difficult to cover properly. To improve coverage, and adherence, many fungicides have adjuvants, or spreader-stickers. Usually, the label alerts the user to these problems. Some fungicides, like Daconil (Fig. 22), leave a residue that makes observing coverage simpler. Many find the residue aesthetically displeasing. In deciding a spray program, it is often difficult to combine good coverage and no residue.

Ultimately, it is your decision—black spots or white residue.

Applying the chemical at the appropriate frequency

Your work isn’t done after applying the fungicide. The first fungicide application establishes a barrier on the plant surfaces. Continued application of fungicides in rotation is needed to keep the barrier active and effective against the disease-causing agent. The fungicide label usually states the frequency of reapplication (usually 7-14 days, although our Subdue example (above) is 2-4 months). A key difference between synthetic and natural fungicides become apparent here: Organic fungicides require more frequent application as they quickly are washed off, or break down, usually within several days to one week. Synthetic fungicides usually have greater than 10-day re-application (assuming plants have not received more than 1” of rain that is capable of washing off the fungicide). These fungicides also oxidize and break down when exposed to sunlight. Regardless of which fungicide you chose, re-application or rotation with another fungicide is needed to keep the fungicide barrier active.

Figure 23. By the time you see spots, it is often too late for a fungicide to effectively manage the problem. The leaf above may me producing over 100,000 spores!

Applying chemicals after you see spots (Fig. 23) is often not effective in managing most diseases. Remember that fungicides protect new growth from infection, so it will take time before you see any effect from the fungicide. This means multiple applications will be required, too!

Two other factors impact application frequency: Plant growth and rainfall. The rate of plant growth affects barrier completeness. As the plant continues to grow, new leaves and shoots appear. This tissue is unprotected, and vulnerable to infection. Repeated application of fungicides protects new growth. Rainfall also impacts the frequency of reapplication. Repeated or frequent, heavy rainfall (or overhead watering) can remove the barrier. If excessive rainfall, or rapid growth of the plant occurs, the shorter interval between sprays should be used. This protects any new growth, and any growth that has had the previous application of fungicide washed off. If plant growth is slower, or less watering has occurred, the longer suggested interval should be used as a guideline.

Fungicide Rotation

Rotating your fungicides is the simple act of switching from a fungicide with one FRAC Code, to another fungicide with a different FRAC Code (Table 2). This is done to reduce the risk of fungicide resistance from evolving (Fig. 24).

Figure 24. Over time, and with repeated application, the fungicide-resistant isolate becomes the only survivor, allowing it to reproduce and evolve. Eventually, Fungicide X will be completely ineffective against the pathogen.

Every time certain fungicides are used, there is a chance that the target organism may develop resistance. Many of the most effective fungicides are no longer effective because of fungicide resistance. With newer synthetic fungicides, which kill in a very specialized fashion, the risk of resistance is much, much higher. For this reason, it is important to develop and implement a strategy to prevent the resistance from developing.

Over time, the resistant strain replaces all other strains and the disease becomes increasingly difficult to control (Fig. 24). To prevent this from occurring, many fungicide labels provide information to assist you in developing good rotations. By rotating, or rotating and tank mixing your fungicides, you reduce the risk of fungicide-resistant fungal pathogens evolving and extend the useful life of “favorite fungicides.” In returning to our example a final time, several rotation partners exist. By using a phosphorous acid fungicide (e.g., AgriFos, Aliette, Vital, Alude) we have switched to a different mode of action, or a different way that the fungicide kills the fungus. This group of fungicides has the unique ability to be applied to the foliage and protect the roots; it can also be used as a drench and protect the foliage in addition to the roots. Rotating this group of fungicides with Subdue Maxx should provide adequate control of not only your root rot problems, but also your aerial blight, assuming that resistance is not an issue. Other fungicides that can be used in rotation include Stature, Orvego, or Adorn), depending upon the location (nursery, greenhouse, landscape, interiorscape, etc.).

To prevent fungicide resistance from occurring, a comprehensive management strategy should be implemented before resistance develops. Some key tactics to include in your management strategy include:

- Implement good plant health practices. The incorporation of disease-resistant cultivars, proper planting and fertilization, and sanitation reduces the reliance on fungicides, thereby reducing the risk of their over-use and Scout regularly to prevent disease establishment.

- Use the recommended dose as stated on the label. Many fungicides have been extensively tested to identify the optimal rate. Cutting the rate results in a sublethal dose that is not only ineffective for disease management but increases the risk of

- Minimize the number of fungicide treatments used per season. Excessive use of a site-specific fungicide increases the likelihood of resistance. By reducing the number of applications of site-specific fungicides to only when needed, the likelihood of resistance developing is reduced.

- Avoid consecutive applications of site-specific fungicides. When choosing a fungicide, do not rely solely on a one fungicide with a site-specific mode of action. Maintain a diversity of fungicides with different modes of action that provide broad-spectrum disease control by differing modes of action. There is no one, best fungicide– There are, however, multiple fungicides with different efficacies for different diseases (Table 2). Many single- site fungicides are highly effective by themselves, but to reduce the risk of resistance use them as part of a tank-mix with another fungicide of a different family or used in a rotation or alternation of multiple fungicide Avoid consecutive applications of any site-specific fungicides.

| Group Code1 | Fungicide Family2 or Class | Common Name | Example Trade Name | Risk of Resistance3 |

| 1 | benzimidazole or MBC | thiophanate-methyl | 3336®, Cleary’s 3336® | high |

| 2 | dicarboximide | iprodione | Chipco 26GT®, Iprodione Pro 2SE® | medium to high |

| 3 | demethylation inhibitor (DMI) | bayleton | Bayleton®, Strike® | medium |

| metconazole | Tourney® | |||

| myclobutanil | Eagle®, Systhane® | |||

| propiconazole | Banner Maxx®, Propiconazole® Mix partner of Concert II | |||

| tebuconazole | Torque® | |||

| triflumizole | Procure®, Terraguard® | |||

| triforine | Funginex®, Saprol® | |||

| triticonazole | Trinity® | |||

| 4 | phenylamide (PA) | mefenoxam | Subdue Maxx® | high for downy mildew and Pythium; low for Phytophthora |

| 5 | amines, morpholines | piperalin | Pipron® | low to medium |

| 7 |

succinate dyhydrogenase inhibitors (SDHI)

|

benzovindiflupyr | Mix partner of Mural® | medium |

| boscalid | Mix partner of Pageant® | |||

| fluopyram | Mix partner of Broadform® | |||

| flutalonil | Prostar® | |||

| fluxopyroxad | Mix partner of Orkestra® | |||

| 9 | anilopyrimadine (AP) | cyprodinil | Mix partner of Palladium® | medium |

| 11 |

quinone outside inhibitor (QoI).

|

azoxystrobin | Heritage® | high |

| fenamidone | Fenstop® | |||

| fluoxastrobin | Fame SC®, Disarm® | |||

| pyraclostrobin | Mix partner of Orkestra®, Pageant® | |||

| trifloxystrobin | Compass® | |||

| 12 | phenylpyrrole (PP) | fludioxonil | Medallion® | low to medium |

| 14 | aromatic hydrocarbons | dicloran | Botran 70® | low |

| etridiazole | Terrazole®, Truban® | |||

| 17 | hydroxyanilide | fenhexamid | Decree® | low to medium |

| 18 | antibiotic streptomyces | streptomycin | Agri-Mycin®, Agri-Step® | low to medium |

| 19 | polyoxin | polyoxin D | Endorse® | medium |

| 21 | cyano-imidazole | cyazofamid | Segway® | unknown |

| 21(P)4 | host plant defense inducers, systemic acquired resistance (SAR) | acibenzolar-S-methyl | Actigard® | low |

| harpin | Messenger® | unknown | ||

| 28 | carbamate | propamocarb | Banol® | low to medium |

| 40 | cinnamic acid | dimethomorph, mandipropamid | Stature SC® Micora | low to medium |

| 43 | benzamides | fluopicolide | Adom® | unknown |

| 45 | quinone inhibitor | ametoctradin | Orvego® | unknown |

| 49 | piperidinyl | oxathiapiprolin | Segovis® | unknown |

| M | multi-site activity chloroalkythios | captan | Captan® | low |

| multi-site activity chloronitrile | chlorothalonil, chlorothalonil + propiconazole | Bravo®, Daconil Ultrex, Daconil Weatherstik® Mix partner of Concert II® | low | |

| multi-site activity dithiocarbamate | mancozeb, maneb, dimethyldithio-carbamate | Mancozeb®, Dithane®, Protect DF, Thiram® | low | |

| multi-site activity inorganics | copper | Champ®, Kocide 3000®, others | low | |

| sulfur | Microthiol Disperss®, sulfur | unknown | ||

| M(33) | multi-site phosphonate | fosetyl-aluminum | Aliette® | low to medium |

| phosphorous acid | Alude®, BioPhos® | low to medium | ||

| U(15) | piperidinyl | oxathiapiprolin | Segovis® | unknown |

1 FRAC code is listed in parentheses under the EPA Group code when the codes differ. Neither system includes biofungicides.

2 For the sake of consistency, group codes, fungicide classes, fungicide names, and abbreviations are those used by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) and by the EPA Office of Pesticide Programs.

3 Resistance risk is considered high when resistance has already been reported; medium risk is associated with less frequent resistance development, or when more than one gene is involved, and the risk is considered low when the fungicide has multi-site activity.

4 Although similarly described, the modes of action are different.

Developing a tank-mix or fungicide rotation

There are two tactics that can be implemented to reduce the risk of resistance developing in fungicides with a single-site mode of action: Tank-mixing and fungicide rotation. Tank-mixing consists of mixing a fungicide with a high risk of resistance with a fungicide with a lower or negligible risk of resistance (Table 2). Fungicide rotation is a strategy where fungicides from different families are used in alternation with one another to prevent the back-to-back treatment with any one site-specific fungicide. Both techniques are effective at reducing the selection pressure of an at-risk fungicide by reducing the time of exposure, and by potentially suppressing any newly developed, resistant strains.

The proper choice of a tank mix, or rotation partner in a fungicide resistance management program is critical. To develop an effective tank mix or rotation:

- Be sure that you use fungicides with different Group Codes (Table 2), which denote different fungicide families. Keep in mind that fungicides with different trade names can belong to the same chemical family!

- Tank-mix or rotate with a partner fungicide that is a multi-site inhibitor (Group Code M).

- Carefully read the label to determine if any mixing incompatibilities may prevent a fungicide from use in a rotation or tank mix.

Fungicide rotations can be simple or complex, depending upon the problem, and the pathogen causing that problem. For example, a Septoria, Myrothecium, or Alternaria leaf spot may be readily controlled by rotating a fludioxonil-based fungicide (Group Code 12) with a chlorothalonil containing fungicide (Group code M), thereby minimizing the risk of resistance in the Group Code 12 fungicide. Other diseases that are more difficult to control may require a more elaborate rotation. For example, downy mildew on snapdragon or lamium may require a rotation of:

- a dimethomorph based fungicide (Group Code 40), followed by

- mancozeb or copper (both Group M);

- this application would then be followed with a phosphorous acid based- fungicide [Group Code M(33)], later followed with

- mancozeb or copper again (Group M).

This rotation could only be repeated twice with the Group 40 fungicide, as its use is limited to two applications unless it is tank-mixed. If the Group 40 fungicide was applied in a tank mix with mancozeb or chlorothalonil, then it may be used up to four applications per season. Remember, tank-mixing or rotating fungicides between different classes reduces the possibility of resistance development. This is important as most labels on the newer, site-specific fungicides have strict use recommendations to minimize the risk of fungicide resistance and protect the long-term efficacy of the product. By carefully following these recommendations, and using fungicides with different group codes, diseases and fungicide resistance can be carefully and effectively managed.

FUNGICIDE RESISTANCE MANAGEMENT

Fungicides are important tools for managing ornamental plant diseases. There are many different fungicides and numerous methods of classifying them. To prevent fungi from developing resistance to these products, it is important to understand how they are classified, and how to use them to prevent resistance from occurring.

Fungicide Class

One way to classify fungicides is by their chemical structures or modes of action — the specific ways the fungicides affect a fungus. Fungicides that share a common mode of action belong to the same fungicide class (sometimes referred to as a fungicide family) (Table 2). Unfortunately, if a fungus is resistant to a specific fungicide, it is usually resistant to all the fungicides within that fungicide class. Most classes of fungicides have what are referred to as Fungicide Resistance Action Committee Codes or FRAC Codes (Fig. 25). This is a simple numbering system that allows you to manage the pesticides quickly determine what fungicide you can use for rotation or tank mix.

Target Site

Fungicides are also characterized by their specificity. Site-specific fungicides react with one very specific, very important biochemical process, called the target site. For example, a fungicide target site could be the specific proteins involved in cell wall biosynthesis, RNA biosynthesis, or cell division. Site- specific fungicides target these specific processes, which prevents the fungus from growing and ultimately causes its death. They are more prone to resistance.

Multi-site fungicides have multiple modes of action, so they affect multiple target sites, and simultaneously interfere with numerous metabolic processes of the fungus. These are older fungicides like chlorothalonil, mancozeb, sulfur and copper.

Fungicide resistance means a once useful fungicide will no longer work against a disease that it was once able to manage. This is very common in single, site-specific fungicides. If a single fungicide continues to be used, the fungicide-sensitive portion of the population is suppressed over time, and only the fungicide-resistant portion of the population remains, which goes on to reproduce and make up the majority of the population. Eventually, the fungicide is ineffective because this majority of the fungal population is no longer susceptible to it.

In conclusion….

When deciding on which fungicides to use, consider how and when the disease strikes, which fungicides are most effective, and other problematic diseases that you may be able to manage. Like the self-help book “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People,” effective fungicide use requires that you be proactive and responsible for your plants’ health. By beginning with a goal of healthy plants, and, to quote Covey “Putting first things first” (diagnosis, research, identifying the best products and their rotation partners) you can proactively manage your plants, nursery, greenhouse, or landscape along with your fungicides.

A final note: The role of the state Extension specialist is to assist the grower or landscape manager in managing plant health problems. Please feel free to reach out if you have a question.

Janna L. Beckerman

Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist

Department of Botany and Plant Pathology–Purdue University

915 West State Street

West Lafayette, IN 47907-2054

765.494.4628

Ornamental Fungicides Overview

Adorn® – provides control of Pythium and Phytophthora and downy mildew in ornamental plants. MRR FRAC 43.

Avelyo® – is a next-generation DMI without plant growth regulator effects, or residue. MRR FRAC 3.

Agri-Fos® – Registered for use on ornamentals, bedding plants, greenhouses, and landscapes. Compatible with most commonly used fungicides, but do not apply to plants that are heat or moisture stressed. Do not apply to plants that are in a state of dormancy. LRR FRAC Code 33.

Aliette® – Registered for use on ornamentals, bedding plants, greenhouses, and landscaping situations. Do not combine or use within 7 days of copper based fungicides. Do not tank with flowable Daconil, fertilizers, spreader-stickers, or wetting agent. LRR FRAC Code 33.

Alude® – For control of various plant diseases including black spot or scab in apple, downy mildew, Phytophthora & Pythium in ornamentals & bedding plants, Phytophthora in conifers, Phytophthora and Pythium diseases associated with stem and canker blight. LRR FRAC Code 33.

Banner MAXX® – Banner Maxx is a systemic fungicide labeled for use on ornamentals and field nurseries, but not greenhouses. Do not use on African Violets, Begonias, Boston fern, or Geraniums. HRR FRAC Code 3.

Banol® — a carbamate fungicide used for the systemic control of Pythium on ornamentals. Unknown, multi-site mechanism of activity provides low to moderate risk of resistance. Also labeled as Previcur®. LRR/MRR FRAC Code M(28).

Banrot® – is a pre-mixed, broad-spectrum fungicide for the control of soil borne diseases in ornamentals and nursery crops. Phytotoxic if rate is exceeded; May result in toxicity to sensitive plants. LRR FRAC Code 1+14.

Bayleton® – Systemic fungicide controls many major diseases on bedding plants, foliage plants, shrubs, and shade trees in nurseries, garden centeres, and greenhouses. Absorbed quickly and works systemically, keep rain fast for 30 minutes. Is compatible with many insecticides and fungicides. Also marketed under the trade name Strike®. HRR FRAC Code 3.

Chipco 26019® – Chipco is a broad-spectrum broadly labeled for many ornamental flowering and foliage plants. Chipco is compatible with most commonly used fungicides. Do not use as a soil drench on impatiens, or pothos. HRR FRAC Code 2.

Cleary’s 3336® – is a broad-spectrum systemic fungicide, compatible with many commonly used pesticides. Do not mix with copper compounds. Also packaged as Transom® 50WSP, and OHP 6672®. HRR FRAC Code 1.

Compass® – is a strobilurin fungicide with protective and curative activity, effective against a broad range of pathogens (fungal leaf spots, powdery mildews). Do not use on Poinsettia bracts, Violets, New Guinea impatiens, or Petunias. HRR FRAC Code 11.

Contrast® – A systemic fungicide effective against basidiomycetes (e.g., rusts, rhizoctonia, Sclerotium rolfsii) for use in the greenhouse, shade houses, and field grown nursery stock. Continuous agitation required throughout application. HRR FRAC Code 7.

Daconil Ultrex ® – Listed for use on ornamentals and trees to control Leaf Spots, Rust, Blights, Stem and Crown Rots, Mildews, Scab, Molds and other listed plant diseases. For Use On: Flowers, Shrubs, Shade Trees. LRR FRAC Code M.

Decree® – Listed for botrytis control on ornamental plants, ornamental crops, forestry conifers and non-bearing fruit trees and vines. Compatible with most commonly pesticides. Rotate chemicals to avoid resistance. HRR FRAC Code 17.

Eagle® – is a systemic fungicide labeled for use on landscape, greenhouse and nursery ornamentals. The addition of a spreading agent will improve coverage. Exceeding recommended labeled rates can result in thickened leaves, shortened internodes, and foliar greening. HRR FRAC Code 3.

Empress Intrinsic® – is a strobilurin fungicide for root and crown pathogens for greenhouse and nursery growers. The active ingredient, Pyraclostrobin, is a strobiliurin. HRR FRAC Code11.

Fenstop® – A broad-spectrum foliar fungicide fungicide used for the prevention of disease in greenhouse ornamentals. Although not a strobilurin, its mode of action is the same. HRR FRAC Code 11

Fore 80WP® — is a broad spectrum protectant fungicide for outdoor or greenhouse grown plants. The addition of a surfactant will improve performance by providing more uniform spraying. Compatible with boron and oils. LRR FRAC Code M.

FungoFlo® – Broad-spectrum systemic fungicide for field, greenhouse, interior, and plantscapes. Do not mix with copper based materials, or highly alkaline pesticides. LRR FRAC Code M.

Heritage® – Heritage is a systemic, broad-spectrum, strobilurin fungicide with preventative and curative properties for use on ornamentals, and landscapes. Care must be taken with use near apples, and on ornamental crabapple. HRR FRAC Code 11.

Kocide 3000® — a copper hydroxide based fungicide labeled for the control of both bacterial and fungal diseases in the greenhouse or shadehouse, or on conifers. Do not mix with Aliette, or any compound that results in a solution with a pH less than 6.5. LRR FRAC Code M.

Medallion® – is a protectant fungicide for control of certain foliar, stem, and root diseases in ornamentals grown in interiorscapes, field, forest, and container nurseries, residential and commercial landscapes, greenhouses, lath and shade houses, or other enclosed structures. Some phytotoxicity reported on Geranium, Impatiens or New Guinea impatiens. HRR FRAC Code 12.

Mural® – is a broad spectrum 7-11 fungicide that is xylem mobile, translaminar, and controls a broad range of plant pathogens. MRR FRAC Code 11+7.

Orkestra Intrinsic® – is the next generation 7-11 fungicide. It controls both true fungi and some oomycetes. MRR FRAC Code 11+7.

Pageant® – is a broad-spectrum combination of Boscalid and Pyraclostrobin. Moves systemically and also moves translaminarly through the leaf to untreated top or underside of the leaf. MRR FRAC Code 11+7.

Phyton 27® – is a surface disinfectant that can be used as a bactericide and fungicide. Do not tank mix with the adjuvant B-9, use within 7 days of B-9 application, or apply with acidic compounds like Aliette. LRR FRAC Code M.

Pipron® – a fungicide to control powdery mildew in the greenhouse, and other structures with an impermeable roof. Do not use with Pentac® Aquaflow and Mavrik® Aquaflow. LRR FRAC Code 14.

Previcur® – a carbamate fungicide used for the systemic control of Pythium on ornamentals. Unknown, multi-site mechanism of activity provides low to moderate risk of resistance. Also labeled as Banrot. LRR/MRR FRAC Code M(28)

Segovis – is one of the newest fungicides for the control of Phytophthora. It has strong activity and systemic properties provide long-lasting control when applied as a drench or foliar spray at low use rates. MRR FRAC Code U15.

Segway O® – is a protectant fungicide controls Pythium, Phytophthora, and downy mildew diseases on ornamental plants grown in commercial greenhouses and nurseries. MRR FRAC Code 21.

Spectro 90WDG® – A combination fungicide with broad-spectrum control of diseases for ornamentals. Do not mix with copper based materials, highly alkaline pesticides, pesticides, surfactants, or fertilizers. Requires agitation. Do not apply to: Swedish Ivy, Boston Fern, Or Easter Cactus. LRR FRAC Code M+1.

Strike® – Systemic fungicide controls many major diseases on bedding plants, foliage plants, shrubs, and shade trees in nurseries, garden centers, and greenhouses. Absorbed quickly and works systemically, keep rain fast for 30 minutes. Is compatible with many insecticides and fungicides. HRR FRAC Code 3.

Stature DM® – offers protective, curative and antisporulant activities against several pathogens, including downy mildews, Phytophthora root, crown and stem diseases, but not Pythium. HRR FRAC Code 15.

Subdue MAXX® – A systemic fungicide for use in nurseries and ornamentals for control of oomycetes (Pythium, Phytophthora). Do not use more than once every 6-12 weeks depending on crop type. FRAC Code FRAC Code 4.

Terraguard 50WP® – Terraguard provides excellent protectant activity against Botryis, Alternaria, powdery mildew, rusts, Thielaviopsis, and the fungi that cause damping-off fungi. It systemic. It is labeled for use in greenhouses, shadehouses, nurseries (including Christmas tree/conifer plantations) and interiorscapes. HRR FRAC Code 3.

Terrazol 35 WP® – is a soil fungicide effective for prevention and control of damping off, root rot, and stem diseases caused by Pythium and Phytophthora in ornamentals and nursery

crops. MRR FRAC Code 14.

Truban 30WP® – is a soil fungicide effective for prevention and control of damping off, root rot, and stem diseases caused by Pythium and Phytophthora in ornamentals and nursery

crops. MRR FRAC Code 14.

ZeroTol® – A broad-spectrum contact disinfectant, algaecide/fungicide used as a preventative treatment for ornamentals and turf. Stops disease and algae on contact. Has a zero REI. Some phytotoxicity reported in conifers. LRR FRAC Code M.

Zyban® – A broad-spectrum premix of a systemic and contact fungicide for use in turf, landscapes, ornamental, and nurseries. Do not use on French Marigolds, or New Guineas. LRR FRAC Code1+M.

Resistance Risk Key:

- LRR—Low Risk of Resistance

- MRR—Medium Risk of Resistance

- HRR-High Risk of Resistance.

FRAC Code-group codes provided by chemical companies. When developing effective fungicide rotations to prevent the development of resistance, choose chemicals of different group codes to use in alternation, or as mixes. See Table 2.

This list is in no way comprehensive. Inclusion does not imply endorsement and exclusion does not imply discrimination.

- Plant disease consists of _____________problems:

- Biotic

- Abiotic

- Organismal

- A and B

- B and C

- (True or False): Water-molds are a type of bacteria.

- Vectors:

- Transmit plant pathogens

- Are epidemiological units

- Toxins that cause plant disease

- All of the above

- The disease triangle is composed of

- Host, insect, people

- Environment, pathogen, people

- Time, vectors, disease

- Pathogen, host, environment.

- Time, space, humidity

- A disease cycle describes

- How insects feed

- How a pathogen infects a plant

- How the environment impacts disease

- All of the above

- (True or False): Plant disease resistance is one of the most efficient and effective methods to control plant diseases.

- (True or False): A quarantine is one way to exclude plant pathogens.

- When spraying a plant, appropriate frequency means .

- Applying a fungicide once

- Applying a fungicide as per label recommendations

- Applying a fungicide every week

- Applying fungicides as needed.

- (True or False): A fungicide rotation is the simple act of switching from a fungicide with one FRAC Code, to another fungicide with a different FRAC Code.

- Plant disease management consists of:

- Diagnosis

- Research

- Identifying appropriate pesticides

- all of the above

- none of the above

Answers to Review and Study Questions

- D

- False

- A

- D

- B

- True

- True

- B

- True

- D