Research with babies and their families fuels early ASD detection research for HHS faculty

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

A.J. Schwichtenberg, associate professor of human development and family studies

Sleep health is key for optimal development in children but especially for children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

According to research by A.J. Schwichtenberg, an associate professor in Purdue University’s Department of Human Development and Family Studies, sleep problems for children with ASD are more than just a parent concern. Sleep problems may inform our understanding of the complex developmental pathways of many children who develop ASD.

“For individuals with autism, up to 80% have comorbid sleep problems, which is actually more common than any other diagnostic feature,” Schwichtenberg said. “My work not only looks at the rates of sleep problems for children with autism and their families, but it also looks at sleep problems as a potential mechanistic pathway to autism.”

The glymphatic system in the brain is a target area for Schwichtenberg’s research. This newly discovered system is in charge of circulating cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) in the brain, which is most active during sleep. In a partnership with Yunjie Tong, an assistant professor in Purdue’s School of Biomedical Engineering, Schwichtenberg assesses glymphatic system functions while participants are awake and asleep to index change within the system. Schwichtenberg’s long-term goal is to apply this work to the study of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease.

In A.J. Schwichtenberg’s lab, students learn to use actigraphy, a small wrist worn device that measure activity which can be converted into rough estimates of sleep and wakefulness. Here a student is wearing an actigraph and is plugging another one in to download the data.

“Sleep is an inherently neurological process,” Schwichtenberg said. “Similarly, autism is a neurologically based process. My work is at the intersection of understanding how normative processes like sleep can relate to developmental pathology in disorders like autism.”

For most, sleep is a routine function. Schwichtenberg studies other routine behaviors between caregivers and children with ASD. For the past four summers, she partnered with Purdue’s Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences to offer eight-week clinics in a study titled “Family Routines Intervention for Children with Social Communication Difficulties.” Schwichtenberg is currently analyzing data from the 2020 cohort.

Through everyday activities like changing diapers and reading storybooks, Schwichtenberg investigated how the children vocalized and held attention during these communicative moments. Interventions that best fit the families are then implemented: home-based strategies the caregivers implement themselves, in-clinic visits to the Speech-Language Clinic at Purdue, or private teleheath sessions with a licensed speech-language pathologist and graduate clinicians.

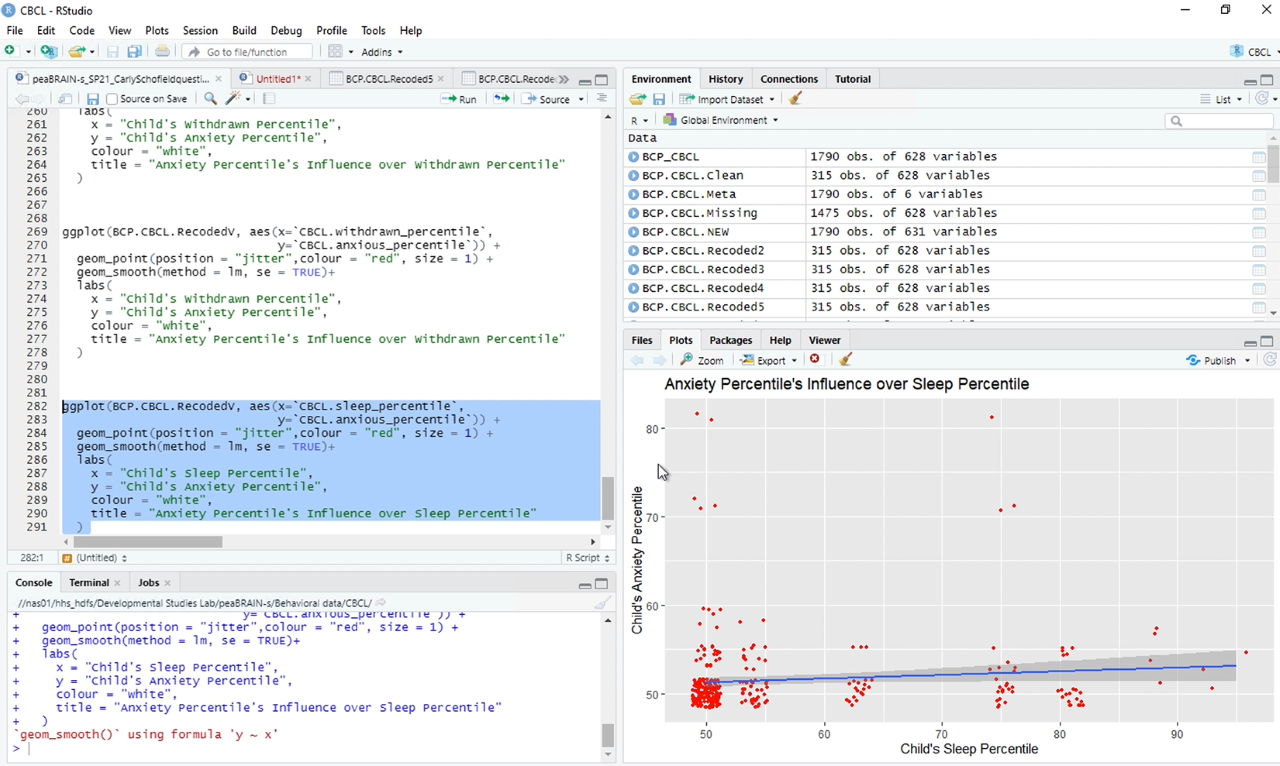

Students learn R, a statistical analysis package, in A.J. Schwichtenberg’s lab. This is a screen shot of their work.

This work was inspired by the lack of interventions available in Indiana for very young children with ASD. In her work, Schwichtenberg found developmental markers of ASD in children as young as 18 months — a few even younger. This arm of her work is dedicated to filling this gap to help families with young children showing early signs of ASD.

“It was gut-wrenching,” she recalled. “We have to have something to offer these families. It’s unethical to say we have concerns but no support to offer.”

At the end of each study, families receive detailed reports that they take home with them. Working with these families has been a fulfilling way to bring her research to real people who need help.

“This is our feel-good project,” Schwichtenberg said. “Through this project, we felt like we could give back to families.”

A passion for inclusivity

Carolyn McCormick, assistant professor in the of human development and family studies

Some high-tech equipment goes into ASD research in the College of Health and Human Sciences. EEG, MRI, high-powered microscopes, data-crunching computers and Velcro. Yes, Velcro, that magical material that helped keep your shoes on when you were a toddler.

An extension to a previous visual processing research project that measured the attention, cognition and learning in young adolescents with ASD, Carolyn McCormick, assistant professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, found the GoPro cameras and headbands too clunky for her new subjects, who were infants and toddlers. She fashioned better-fitting, comfortable headbands that hold a smaller camera on a young child’s head. The caregiver fits the equipment around the head of the child with simple Velcro fastening.

McCormick has already studied the visual sensory behaviors in children with ASD by monitoring eye-tracking while the subject watches videos or still images. To get a grasp at how they perceive their 3D environments, the camera is strapped to the child’s head for hours, collecting where and how long they look at people and objects.

Carolyn McCormick’s son Weston models the small video camera she uses on her young subjects in her autism spectrum disorder research.

“We’re looking at how primary faces serve infant and toddler development,” McCormick said. “Early in infancy, faces are so important. They’re everything until children start to move around and engage with the world.”

When reviewing the hours of video, McCormick pays close attention to a young subject’s shift in attention during word-learning opportunities. How the child behaves in these situations can give developmental clues to if the child will develop ASD.

McCormick is seeking patterns in where the child looks when the caregiver is speaking to her or him. This could inform target goals for ASD intervention.

The visual work will help understand how young children engage with their environment, but what about families with older children with ASD? McCormick was approached by a Purdue Health and Human Sciences Extension educator for advice on how to support youth with ASD participating in Indiana 4-H, the youth organization dedicated to positive development and mentorship. There are about 130,000 4-Hers in Indiana alone.

“It’s about finding accommodations allowing students with ASD to participate without taking away opportunities from them,” she said.

McCormick contacted all levels of leadership at the Indiana 4-H offices and interviewed officials, volunteers, families and youth with ASD to get an idea of what is offered; what the needs are; and how children with ASD could better participate in events, competitions and volunteer projects. She is currently developing training materials to help the adult volunteers better plan events with children with ASD in mind. Of those events, the cherished county fairs of Indiana are at the top of the list. Educators and parents reported difficulties around accommodations during those events, which influence youth being able to enjoy the traditional summer fun that goes along with 4-H county fairs.

“They can be overwhelming — sensory overload,” McCormick said. “There is a need for better communication and options for students with autism during that fair time … It’s about having accommodations without taking out all of the fun of the fair … I heard of one student that dropped off his project and then left before anything even started. That student also missed out on the opportunity of getting that public-speaking part of presenting their project.”

McCormick’s career goal is to make positive impacts in the lives of people with ASD across Indiana.

“So much more of my work now is directly informed by stakeholders in the community — parents, youth with autism themselves, adults with autism. They help me develop research questions, implement research projects,” she said. “I have several projects now where I’m using qualitative methods to do interviews and focus groups so that we make sure anything that we design or implement will have input from the community.”

The path from sounds to words

Amanda Seidl, professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences

Bridgette Kelleher, associate professor of psychological sciences

There’s much more to infant vocalizations than just nonsensical sounds, according to research by Bridgette Kelleher, associate professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences, and Amanda Seidl, professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences.

Analyzing the utterances of at-risk infants as young as six months could reveal clues to ASD outcomes. Kelleher and Seidl, along with graduate student Lisa Hamrick, comb through day-long recordings to measure the quantity and quality of infants’ vocalizations while interacting with their caregivers.

These recordings have the benefit of capturing “natural” behaviors because they are made in the child’s home environment while they are interacting with familiar people. The infants, whose neurogenetic markers have shown signs of ASD risk, wear vests equipped with tiny recorders. Seidl and Kelleher and teams of skilled graduate and undergraduate annotators use both automated and human tagging systems to examine vocal maturity in these recordings. For example, they tag whether infants are producing canonical babble — distinct syllables that are a combination of a consonant and vowel like “ba” or “ga”.

Amanda Seidl and Bridgette Kelleher utilize small vests with recorders installed inside of them to record baby communications for their research on autism spectrum disorder development.

Through automated systems such as the Language Environment Analysis (LENA) technology, the researchers also monitor the quantity of speech sounds that infants produce. However, infants-speech analysis needs some human interpretation of the quality of that speech which can be costly when conducted solely in the lab. Thus, Seidl, Kelleher, collaborators, their students and citizen scientists on the Zooniverse platform have generated work showing that citizen scientists are quite skilled at separating “ba’s” and “ga’s” from cries, laughs and other non-speech sounds, which helps them to consider how children’s speech is progressing quite quickly and with reduced cost.

“This data and finding efficient and economical ways to annotate this data will help us figure out which babies are more likely to go on to develop ASD versus which ones won’t so that interventions can begin earlier and can be better targeted,” Seidl explained.

Seidl and Kelleher’s work on this project started before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, very little momentum was lost because the research began remotely and has continued as such. This project had to take place in the families’ homes, as an observer’s presence could alter the behavior of the family. Also, the remote nature expands the scope of the work to families nationwide. The equipment is shipped out and the researchers interact with the families over telehealth platforms.

“Using these kinds of recording devices is advantageous in capturing natural behaviors because people forget they are there, especially after 16 hours,” Seidl said. “There’s no strange person in your home reminding you that the recorder is on”.

For this project and other pediatric speech research, families with affected children are essential. Working together with the families makes research breakthroughs most rewarding.

“Our families are always amazingly responsive to research opportunities. Many are eager to share their experiences to build a better future for their child and for other families touched by similar diagnoses,” Kelleher said. “As a clinically focused researcher, it is important to me that the work I do is of value to the communities I am to support. Otherwise, what is the point?”

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.