Purdue HHS researchers uncover connections between word learning and retrieval practice to improve outcomes for children with developmental language disorder

Written By: Rebecca Hoffa, rhoffa@purdue.edu

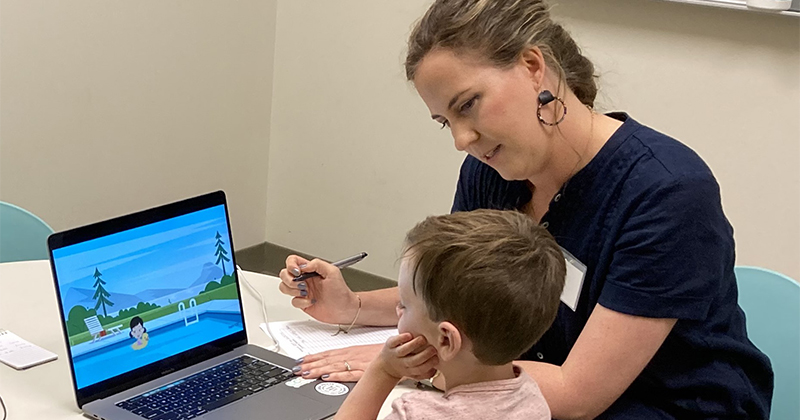

Mariel Schroeder assesses a child as part of the study.(Photo provided)

Children with developmental language disorder (DLD) can be difficult to diagnose, despite the condition being more prevalent than autism spectrum disorder, representing roughly 7.5% of 5-year-olds in the United States, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Laurence Leonard, Rachel E. Stark Distinguished Professor in the Purdue University Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences (SLHS), and Patricia Deevy, SLHS research associate, have been building momentum to understand children with DLD for decades. Recently, alongside College of Health and Human Sciences (HHS) graduate student Mariel Schroeder, the team has made strides in understanding word learning for this group of children through shared book reading.

“We have studied 4-5-year-old kids, but this is a lifelong disorder that affects primarily language ability, although there can be some weaknesses in related areas,” Leonard said. “Language is the most conspicuous difficulty, and that goes on for a long time. Symptoms change with age, and in many instances, these kids have pretty good outcomes, but some level of language weakness remains.”

Leonard’s Child Language Research Lab is entering the 10th year of its R01 grant centered on word learning from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

“Our grant these last 10 years is asking not only if we can help these kids learn words in a better way, but if we include what is called retrieval practice, will that help them further?” Leonard said.

Fellow HHS researchers Sharon Christ, associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Science, and Jeffrey Karpicke, James V. Bradley Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences, have served as important collaborators in parsing the data and understanding retrieval practice as part of this grant.

“It’s only recently where people are applying this well-established idea of retrieval practice to the word learning of children with DLD,” Leonard said. “That’s what our project is really about.”

The researchers have developed novel words to test retrieval practice in both children with DLD and children with typical language development to see its influence on word learning. In several of the studies, the novel words were created to refer to unusual plants and animals that children are unfamiliar with, such as the “nepp.”

The lab creates novel words for unusual plants and animals to test retrieval practice, such as the “nepp.”(Photo provided)

“It turns out that having these retrieval opportunities seems to help the kids who are learning, whether these words are nouns, verbs or adjectives,” Leonard said. “As far as we’ve been able to test, retention of new words is relatively good in these children. If they’ve learned the words in the first place, they’ll remember them one week later with pretty good consistency. So what retrieval practice really seems to help with is the initial stages of learning a word and establishing it in memory.

“Little by little, we’ve been trying to improve our procedure because, in each of our studies, there are a few kids who do not learn the words very well. We want to get everybody’s performance up higher.”

Leonard’s lab also relies on the clinical expertise of graduate students like Schroeder to help identify children as having DLD.

“Thanks to people like Mariel who have the clinical qualifications to evaluate the kids, we can be more confident that these kids really meet the selection criteria of being kids with developmental language disorder,” Leonard said.

Deevy coordinates a variety of aspects of the study, such as the development of the novel words.

“We try to make them easy for a 4-year-old who is already having trouble learning words,” Deevy said. “So we generally stick to one-syllable words, using sounds children are able to produce easily. And there’s a whole literature in psychology about the kinds of things that affect our ability to learn and remember the sound sequences that make up words. So, we try to control for those properties, like how frequently a child would hear a sound or sound combination in English words.”

In creating semantic associations with words, such as associating a new word “nepp” with the meaning “likes birds,” the research team has discovered that children, both with DLD and without, are able to learn the arbitrary meaning — liking birds — surprisingly quickly.

“That also suggests that there are different components of memory where children may be stronger in some areas and weaker in other areas,” Leonard said. “Even if children are below-age level in learning the meanings of words (as in “likes birds”), they are usually better in learning these meanings than in learning the words themselves (as in “nepp”). Remember, the words themselves are these made-up words, and so there are new phonetic sequences that are involved that the children have to remember. That part is their biggest weakness.”

Ultimately, through its gradual progression over the past decade, the team has consistently seen improvement in the children’s word learning using retrieval practice.

“We feel really good about the fact that every study is showing that one effect, at least, as we’re trying to get overall learning higher and higher,” Leonard said.

Currently, the researchers are taking the work one step further by embedding the novel words and retrieval practice in a more naturalistic book reading context.

“Our latest work is trying to have it resemble real world book reading even more,” Leonard said. “What we’re trying to do now is have the characters in the story talk about these funny objects, rather than being mentioned in passing. And like in the real world, where teachers, speech-language pathologists, and parents would actually interject comments themselves about the book, we do the same thing too. We just interject a few spontaneous comments, trying to keep the kids engaged and trying to make it even more realistic. We’re collecting data now on that.”

Although the methodology has only been tested in the lab thus far, the researchers are seeing that retrieval practice has a promising future where clinicians and parents could help children with DLD with their word learning. The eventual idea would be that retrieval practice could be implemented through shared book reading, also called dialogic reading.

“Dialogic reading is a tool that many clinicians use,” Schroeder said. “’Dialogic’ comes from the word ‘dialogue,’ and it portrays the idea that the reading activity becomes more of a shared conversation between the adult and child instead of a child passively listening to a story. It can be hard to translate research into clinical practice, but this study is a first step toward a connection to something a lot of speech-language pathologists and caregivers are already doing with their children.”

Ultimately, the researchers noted that none of their work would be possible without the parents and children in the Greater Lafayette community and surrounding area who participate in the work, whether through the Summer Fun program or by directly signing up for research participation.

“We appreciate our families and the commitment of time and effort they make to come and participate,” Deevy said. “We couldn’t do it without them. This is a great community to do our research in.”

Discover more from News | College of Health and Human Sciences

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.