Purdue researcher focuses on early detection for, strengths within individuals with autism

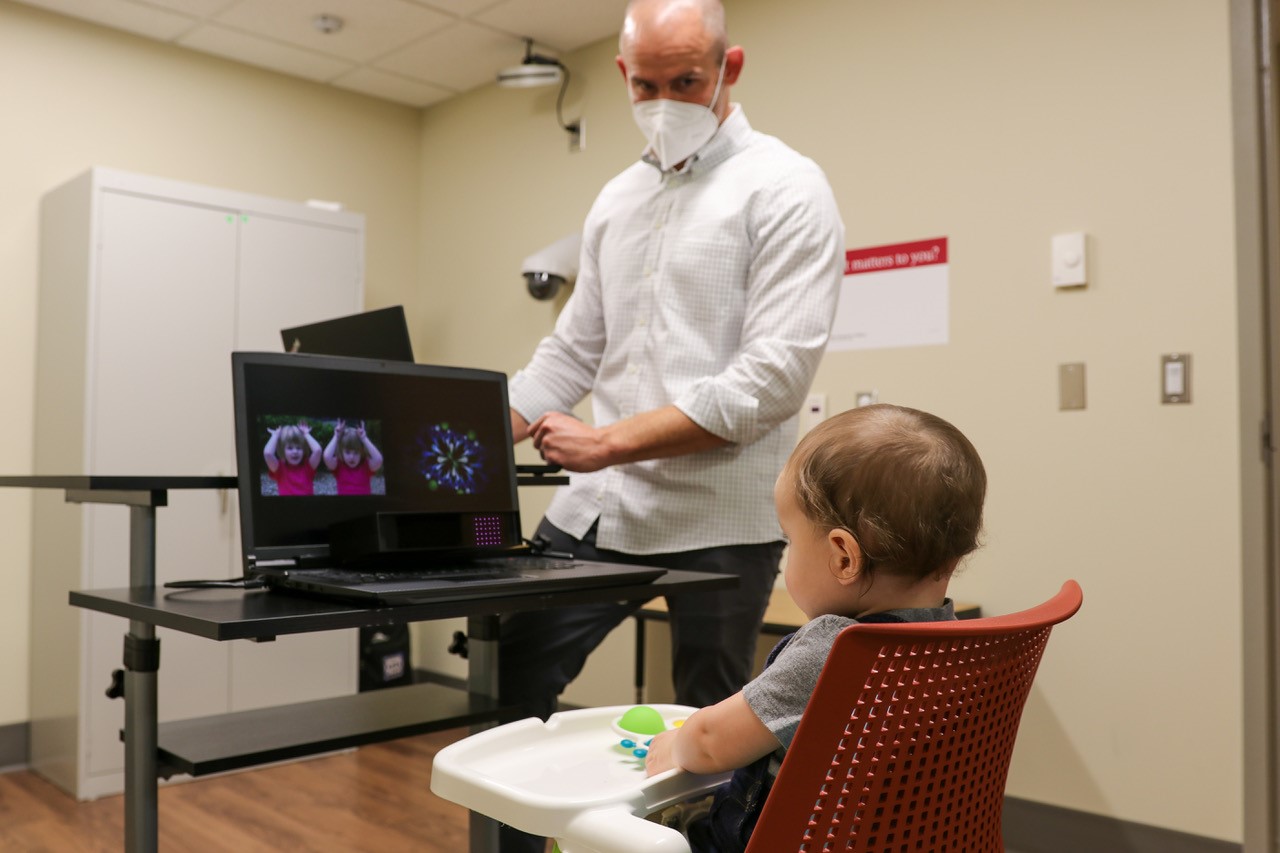

Brandon Keehn, associate professor in the departments of speech, language and hearing sciences and psychological sciences, utilizes eye-tracking technology with a young participant during a recent study.

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Within his Attention and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Lab, Purdue University College of Health and Human Sciences researcher Brandon Keehn, associate professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and Department of Psychological Sciences, utilizes eye-tracking technology for early assessment of toddlers and young children at risk for autism as well as for learning about the strengths of older individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

A focus of his research is translating the methods he uses in the lab toward solving real-world problems. A goal of a current National Institutes of Health-funded research initiative with his wife, Rebecca McNally, clinical psychologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine, is to understand if eye-tracking technology can improve the accuracy of autism diagnoses made by primary care providers (PCP) across the state.

This research has been conducted within Indiana’s Early Autism Evaluation Hub system, a statewide network of community PCPs trained to provide streamlined diagnostic evaluations for children ages 14-48 months at risk for ASD. The goal of this system is to reduce the wait time for early autism evaluation, lowering the age of diagnosis and allowing children streamlined access to interventions that can improve child and family outcomes. This is critical because, today, one in 36 U.S. children are identified as individuals with autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There were, and honestly still are, long waitlists for a diagnostic assessment,” said Keehn, who is also the associate director of the Purdue Autism Research Center. “It may take nine to 12 months to see someone for a diagnosis and then subsequent waitlists for interventions. Ultimately, you could have a child where there were concerns before the age of 2 that may not get access to services until they’re about 4 years of age.”

Additionally, McNally and Keehn found these hubs have about 80% accuracy in diagnoses. Implementing Keehn’s eye-tracking methodology in primary care offices may improve accuracy by giving PCPs another tool to use in their diagnostic decision-making.

This work is also funded by Riley Children’s Foundation.

The eyes have it

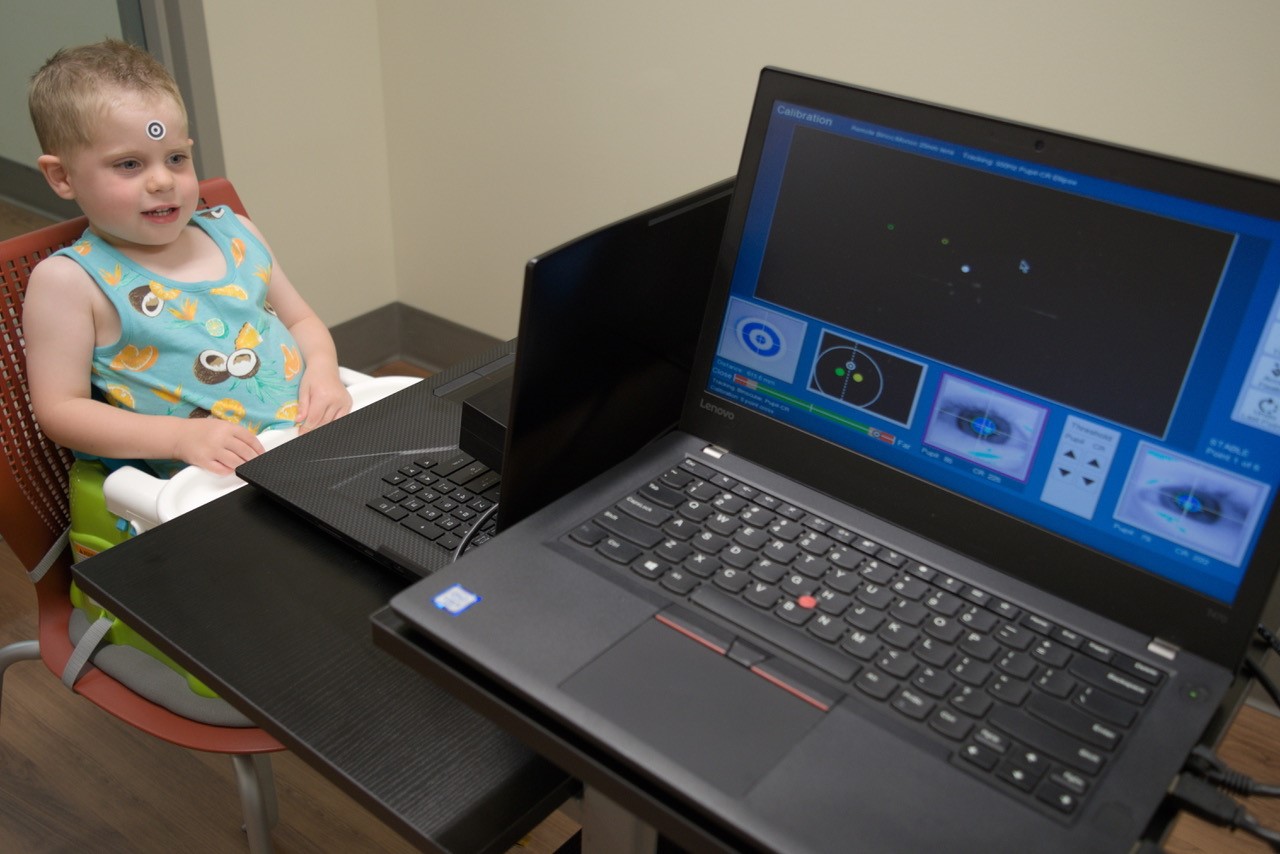

A toddler dons a bullseye sticker on his forehead. This helps the eye-tracking camera monitor the young participant’s “attentional disengagement” or how long it takes the child to move his gaze from one object or scene to another on-screen.

Keehn’s current eye-tracking setup consists of two laptop computers and small cameras set to track the locations of children’s gaze and the size of their pupils as they look at images. For one task, Keehn times how long it takes for the children to move their gaze from one object or scene to another, otherwise known as “attentional disengagement.”

“Some individuals with autism tend have ‘sticky attention.’ That is, they may be more likely to get stuck on something, and then have a hard time shifting their attention from that thing to something else in their environment,” Keehn explained. “With eye tracking, we can measure that.”

While this set-up fits into a backpack for easy transport, it’s still expensive. Another project goal aims at scaling the eye-tracking to just one tablet for easier, more cost-efficient use in a pediatrician’s office.

“If we can train pediatricians in Muncie how to make an autism diagnosis, then families don’t have to travel to Indy. Our work is trying to give those pediatricians one extra tool in their toolbelt to make more accurate diagnoses,” Keehn said. “In the end, it will help reduce disparities that exist in terms of family travel, taking time off from work, and having access to care.”

The work will also improve the content of the eye-tracking work. With help from the Purdue Department of Computer Graphics Technology, traditional experimental stimuli that may become boring to a 2-year-old will be swapped for “gaze contingent” animated videos in the style of popular preschool programming, such as “Cocomelon” or “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood.”

Helping Boilermakers with autism

Another research collaboration, this time with Rose Mason, associate professor in the Purdue special education program, observes Purdue undergraduates with autism as they navigate their classes. The study aims to combat a nationwide higher education trend where students with autism tend not to complete their postsecondary studies at a higher rate than their students with other disabilities and neurotypical students.

“It’s not because these students don’t have the cognitive abilities to complete. In fact, in many cases, they may have greater cognitive abilities than their non-autistic peers,” Keehn said. “We are focusing on their strengths to try to understand how and why students might underperform in the classroom.”

Recognizing problems early in a student’s undergraduate experience could set them up for a better — and therefore longer — postsecondary career.

In Keehn’s lab, participants were given visual search tasks with sounds that recreate “active learning” scenarios, or group projects where discussion and interaction between the students are encouraged. Again using eye-tracking, students with autism performed poorly when they had to complete visual exercises while hearing background voices. They performed better in the traditional, “passive learning” format where the instructor is speaking, and the background noise is null.

“We found that, in a quiet condition, students with autism are much faster than their neurotypical peers, but as soon as you create the noisy conditions, you take away their advantage,” Keehn said. “The difficulty of filtering irrelevant information really comes at a cost for students with autism.”

This work, which is funded by a Launch the Future grant from the Purdue College of Education, can alert programs to accommodations for students with autism in rigorous STEM programs like those at Purdue.

“How can we change the environment, or how can we give students with autism the skills necessary to filter out these irrelevant details?” Keehn said. “We hear first-person perspectives about how differences in how a classroom is structured or how a course is designed can engage students or result in students having a difficult time.

“It’s enlightening to hear about the things we study in the lab can have real-world implications in how individuals perform in the classroom.”

Accentuating the positives

Individuals with autism see the world in a different way than their neurotypical peers. While some may view this as a negative, Keehn and other researchers promote positives within the minds of those with ASD. One example is people with autism can notice minute differences in work situations, especially in STEM fields.

Microsoft made huge initiatives in hiring neurodiverse job candidates for their perspectives and abilities. This push helps with the technology corporation’s diversity practices while utilizing individuals with autism to spot errors in code, for example.

Neurodivergent people have been known to excel in life sciences too. A study by the National Institutes of Health revealed pillars of early scientific discovery — Isaac Newton, Henry Cavendish and even Albert Einstein — most likely worked and excelled while living with various forms of ASD. Newton is believed to be the first documented person with a form of ASD, the paper hypothesized.

Whether it’s job performance at a tech firm or finding the differences in two images in Keehn’s lab, focusing on the strengths of individuals with autism is a research area that can benefit the participants as well as their colleagues.

“One way to reconceptualize or rethink about autism is rather than pathologize some of the differences, highlight and celebrate how those differences can bring about really important contributions,” Keehn said. “Autistic individuals may see the world or see a problem in very different ways and therefore offer very unique solutions.”