Consumer Science alumna advocates for Black mothers through Maternal Action Project

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Bianca Pryor, a Purdue Consumer Science alumna, is the “tester of all the things” at BET network and co-founder of Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project.Photo provided

Black mothers often experience barriers, biases and disparate practices throughout their pregnancies and postpartum experience, according to Bianca Pryor, a Purdue University Consumer Science alumna and co-founder of Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project (MAP).

The foundation strives for equitable, quality care for Black birthing people. It is named after Shalon Irving, a fellow Purdue alumna, mother and former epidemiologist for the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Irving died Jan. 28, 2017, just three weeks after giving birth to her daughter, Soleil. Pryor and Irving’s family believe her death could have been prevented by better care from nurses and doctors after the birth.

“Shalon knew her body so well — you would have thought you were talking to an MD,” Pryor remembered. “But her defenses just eroded. She just became so tired advocating for herself. … When she kept trying to bring it up, nobody heard her. It was completely preventable. Completely.”

Friends of 15 years, Pryor and Wanda Irving, Shalon’s mother, established Dr. Shalon’s MAP with the goal of preventing deaths like Shalon’s. Pryor and Shalon Irving met when they were both graduate students at Purdue and continued their tight bond as the young women earned degrees, established careers and eventually both becoming pregnant in 2016.

Both Pryor and Irving were lucky to have “villages” of support through friends, family, texts, phone calls and Facebook messages. Not every Black birthing person has the luxury of such support, especially throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the idea of most aspects of life being pushed into the digital realm, Pryor established a “village” in her new app, Believe Her. It features anonymous peer support with the mission “to increase awareness of the Black maternal health crisis” while developing strategies to improve health outcomes for Black birthing people and their families. While some mothers have in-person support from their families, others do not. Believe Her puts users in touch with others going through pregnancy as well as dealing with the weeks or months of postpartum mental and physical healing.

The app also features 20 chatrooms, a robust resource section and recommendation chatbots that help tailor the support to the user.

“We’re creating a conversational space and virtual village to have Black birthing people come into it and say, ‘Hey, this happened to me,’” Pryor said. “They can just have a soundboard, or they can give advice as well. It’s a give-and-take relationship in our village. Shalon could have used that additional support in her own situation. We really do believe it’s about strengthening that line of defense and pushing against institutions, power figures that make you feel unheard and not believed.”

Disproportionate maternal health risk

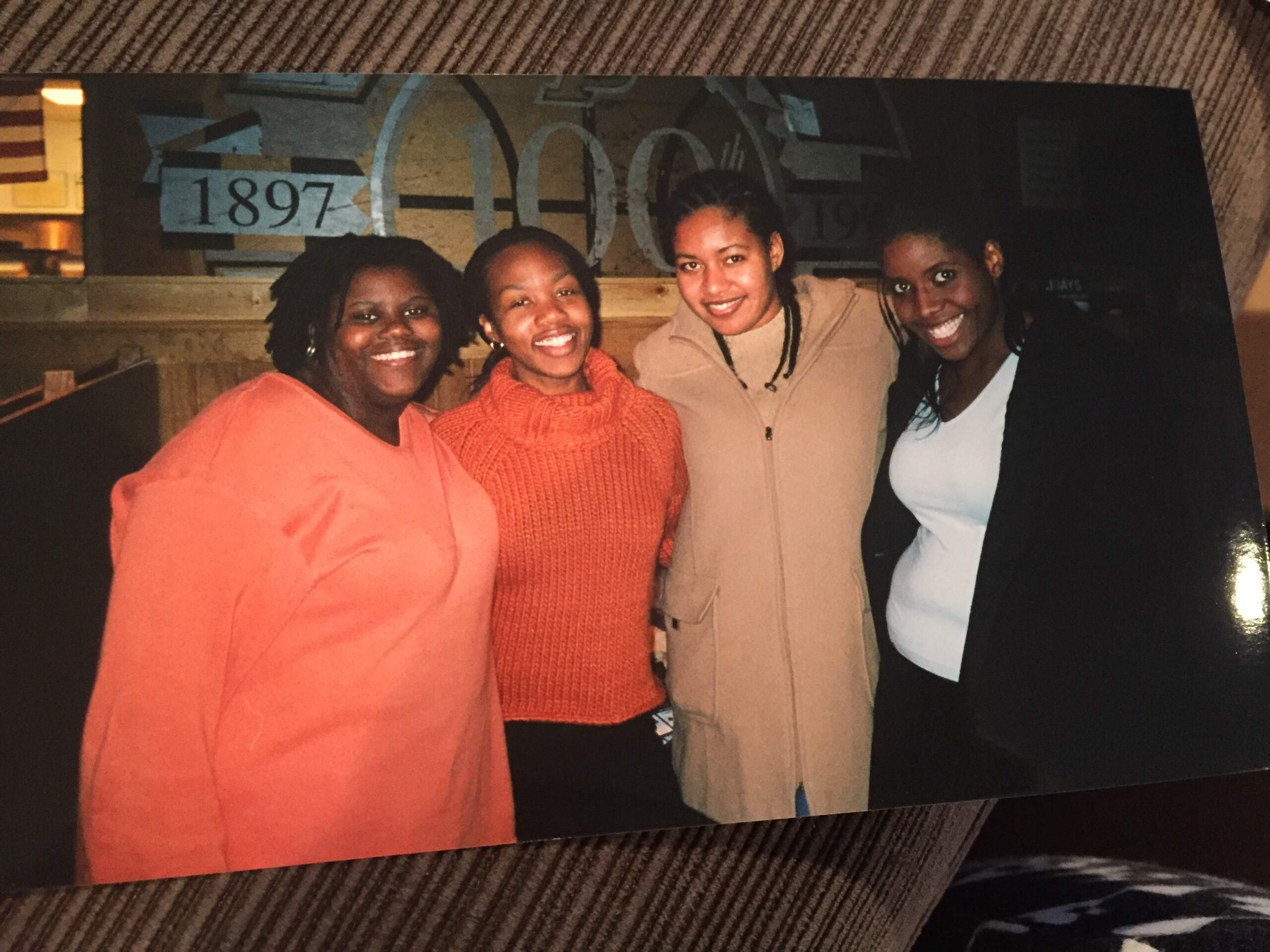

Shalon Irving, left, and Pryor were both pregnant in 2016.Photo provided

According to the CDC, Black mothers are three to four times more at-risk for maternal health complications than white mothers. Both Pryor and Irving’s pregnancies would be classified as difficult. Pryor’s son, Everton, was born 16 weeks premature and had to spend three months in the neonatal intensive care unit. Irving had to deliver Soleil via caesarian. The incision caused major bleeding and initial recovery was difficult. As soon as the incision finally began to heal properly, Irving’s blood pressure became erratic. Only 36, she experienced hypertension and swelling in her limbs.

Pryor said Irving’s death could have been prevented if nurses and doctors listened to her more. According to Wanda Irving, many of her daughter’s concerns were dismissed, and Pryor believes these dismissals led to her friend’s death, which occurred at home shortly after putting three-week-old Soleil to bed.

Shalon was always one to advocate for herself and others, but after constant complaints gone unheard, she became mentally and physically exhausted.

“Weathering is a term that comes to mind, which was actually coined by Geronimus in 1992,” Pryor said. “Black women feel the weight of the world coupled with socioeconomic disadvantages that wear on the physical body — that is weathering.”

There are many reasons why Black birthing people are more at-risk than their white counterparts. Many are stresses they have to endure early, such as wealth disparity and systemic racism. According to research by National Public Radio and ProPublica, “Black women are more likely to be uninsured outside of pregnancy … and thus more likely to start prenatal care later and to lose coverage in the postpartum period.” There is also the feeling of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers. “If they experience discrimination or disrespect during pregnancy or childbirth, they are more likely to skip postpartum visits to check on their own health.”

“We’re trying to help change that narrative, really open the eyes around us,” Pryor said. “Learning how to advocate for yourself is so important but also navigating the medical-industrial complex is so important and knowing what resources you have access to. There is a lot out there. How do you know what is best for you? How do you know what is a valid resource?”

Meeting Dr. Shalon

Pryor still remembers the first time she saw her friend almost 20 years ago.

“It was a BGA event, Black Graduate Student Association,” Pryor recalled. “They had all of the Black grad students together, and I remember Shalon sitting on a piano bench. There was a piano in this room for whatever reason, and I went up to her and introduced myself.”

The students hit it off immediately, initially bonding over their undergraduate experience at historically Black colleges and universities only about an hour away from each other in Virginia.

This photo shows Pryor, middle right, and Irving, middle left, during their time as Purdue graduate students.Photo provided

While Irving thrived in the public health and social science realms, Pryor established an expertise in the consumer behavior and marketing fields. She gained experience as a senior vice president and co-head of communications for System 1 Research before landing at BET, a ViacomCBS company. Pryor is vice president of consumer insights, content optimization and marketing strategy – more simply put, “the tester of all the things” — series, pilots, talent, promos, trailers and movies.

With career success came unexpected pregnancies for both Pryor and Irving. Both leaned on each other throughout their pregnancies. The first months were emotional, and the friends inspired each other from afar as Pryor had moved to New York while Irving was at the CDC’s Atlanta headquarters.

“Our friendship grew, and we experienced a lot of life things together that kept us close,” Pryor recalled.

While Pryor had her son months before the due date, Irving carried Soleil to full term, but caesarian procedures were required. Still, the birth went mostly well, and the baby was healthy.

But then tragedy struck. Pryor and many of Irving’s “village” were stunned. How could this happen? How could a successful, accomplished, young mother like Irving die soon after giving birth?

“It’s still hard. We miss her tremendously. Shalon was a force,” Pryor said. “Shalon had a PhD, a couple master’s degrees, MPH (master of public health) from Johns Hopkins (University). She was brilliant, so smart, but none of that mattered. None of that protected her in the end. It goes back to all of this was preventable. She did advocate for herself. She just wasn’t believed; she wasn’t heard. That’s the unfortunate part because if you think about someone like Shalon, imagine the other vulnerable populations out there who don’t know how to speak up for themselves, don’t know what routes to take, don’t know how to push back on the system. This really is about pushing back on a system that has not truly benefited Black birthing people historically.”

‘Fierce Black feminist’

Pryor credits her years at Purdue for her passion and drive, whether developing an app for Dr. Shalon’s MAP or climbing to her crucial role at BET. Purdue helped ratchet up her critical thinking, exposed her to fierce Black feminists like Maya Angelou and bell hooks, and gave her space to question systems of oppression.

While she never thought she would be among those responsible for putting hit programming like “The Ms. Pat Show” on the air, the R-1 research skills and consumer behavior analytics Pryor learned in her consumer science classes and projects have helped her succeed.

“My experience at Purdue, it was transformative,” Pryor said. “It was a space and a place for me to question everything I was taught, whether that was at home or in undergrad where I studied marketing and Spanish. I think for me, being at Purdue, it upended a lot for me but in a very positive way. It taught me to be a scholar and really take research seriously and understand the full research process.

“I just started to really soak up all of that amazing content and thinking and learning how to be a fierce Black feminist. It’s standing up for yourself and understanding the struggle and finding solutions to the struggle.”

While she ensures quality programming on BET, Pryor and Dr. Shalon’s MAP could ensure pregnant people of color better health outcomes nationwide. The organization is an official endorser of the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, which would aid mothers in finding child care, food security, transportation and housing while extending postpartum eligibility for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children to two years. The bill is currently in the House of Representatives.

“If this can get passed, there’s so much in that bill package that will support not just Black birthing people but all birthing people who have been historically oppressed and who need the support,” Pryor said.

Irving’s daughter, Soleil, right, meets Pryor’s son, Everton. The children’s mothers were best friends until Irving’s 2017 death.Photo provided