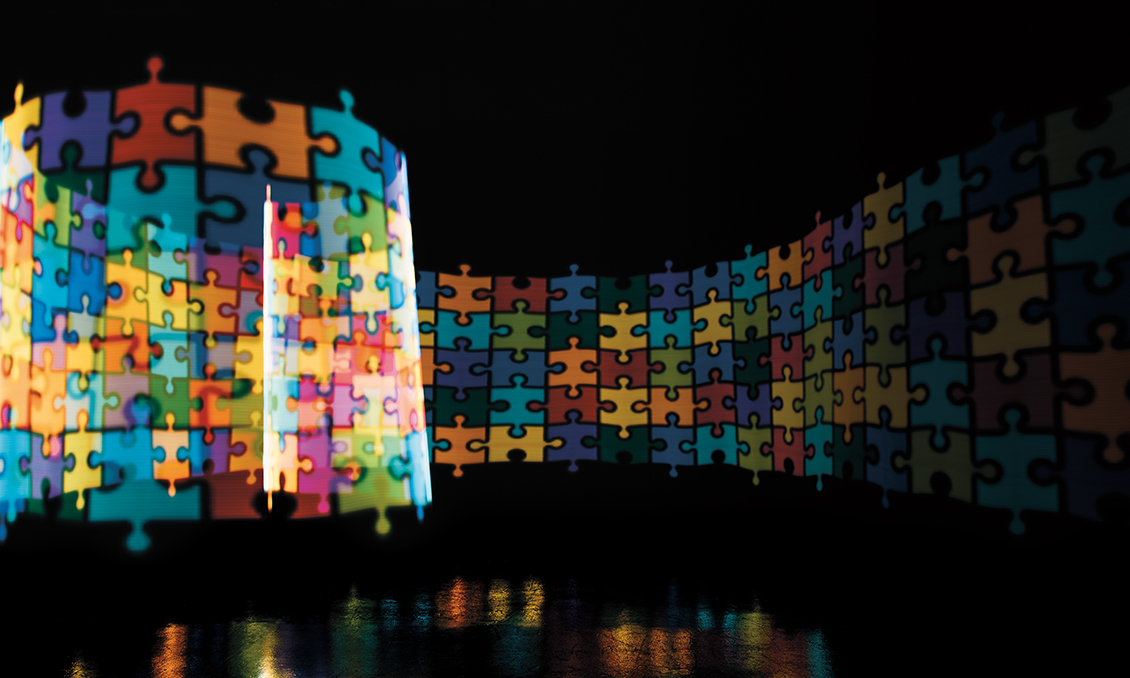

Research Piece by Piece

Pioneering Autism Cluster Breaks Barriers

Story by Amy Raley, photo by Charles Jischke

You remember it well. Before each college semester, you registered for several courses in different disciplines. You learned each discipline separately, by design.

This has long been true for research, too. Today, however, the College of Health and Human Sciences through the multidisciplinary Purdue Autism Cluster is breaking old barriers and forming collaborations unheard of a generation ago. The research cluster is a group of diverse Purdue thinkers who deliberately cross academic boundaries to help people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their families.

The logic behind the cluster is that diverse experts who work together will ask broader and better questions, design superior research projects, and uncover more robust answers than can single-discipline teams.

And the need felt by those in the field to be better and do more about autism is underscored by findings that there are more children with ASD than previously thought. The most recent government numbers say that one in every 45 children ages 3-17 has ASD. That number, which comes from a survey of United States parents, is much higher than its most recent counterpart from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC reported in 2014 that one in 68 children has ASD, but also conceded that the number was too low because it came from medical and school records that didn’t count children who weren’t receiving treatment.

Purposely Upending Research

As chair of the Purdue Autism Cluster, Lisa Goffman keeps a bird’s-eye view of Purdue’s ASD research picture. She continually searches for novel research collaborations and fosters new disciplinary alliances, which enable discoveries for ASD diagnostics and treatment, but also generate hypotheses that may have gone uninvestigated otherwise.

“My role has been facilitating interactivity from very basic to very applied researchers across Purdue,” says Goffman, professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences. “We have mouse models of stereotypic behavior and of perceptual deficit, all the way through human intervention studies.”

In her own research, Goffman studies the coincidence of language and motor deficits in children with an eye toward development-enhancing treatments.

One Sandbox for All

Cluster projects involve researchers from special education programs and the departments of Biological Sciences and Comparative Pathobiology. Also collaborating are faculty in Human Development and Family Studies; Psychological Sciences; Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences; Educational Studies; and Electrical and Computer Engineering.

One Researcher At A Time

We introduce here a few of the Purdue Autism Cluster’s ambitious members and colleagues:

Elizabeth Akey

Purdue graduate students look to Elizabeth Akey, clinical assistant professor of psychological sciences, to show them how. She leads them on their clinical journey toward assessing and working with children with ASD.

As a colleague of the cluster and clinical supervisor for two of the clinics in the Purdue Psychology Treatment and Research Clinics, Akey trains graduate students to assess children and adults when autism or another disorder is suspected, and to use research-proven strategies to help affected families cope and thrive.

Akey says she hopes that increased awareness of autism will lead to greater understanding about the very broad range of behaviors and challenges on the spectrum.

“There are people with an ASD disorder who show what we think of as the classic form — withdrawn, aloof and unable to communicate,” Akey says. “There are also people who go up to everybody they meet and get two inches from their noses and ask, ‘Could I be your best friend? Would you be my dad? Could I go home with you?’”

Akey says parents often don’t realize that some things their child does could indicate autism. She says that whenever parents wonder if they have a child on the spectrum — or their child has persistent worrisome behaviors — they should ask their pediatrician, the teacher or a Purdue specialist, and keep asking until they get the help their child needs.

“Parents must trust their sense of what could be or should be, and ask,” she says. “When they do, they should know that ‘You are showing you care for your child.’ At times during an assessment, parents will feel like they’re betraying their child. They say, ‘Oh yeah, he does that.’ I believe that asking questions is a good and powerful thing, even if it feels awful during the process.”

Laura Claxton

If a toddler isn’t moving in an expected way for her age, her brain might have its own variety of immobility, too — and one inability might cause or contribute to the other. Laura Claxton, associate professor of health and kinesiology, studies whether such relationships could help diagnose ASD and lead to novel development-enhancing therapies.

Her recent work has looked at the different factors that affect how infants and toddlers control their posture.

“Postural control is really important for development,” Claxton says. “If it’s good, it allows infants to sit and stand and walk, which allows them to learn about their environment. Research already has shown that the onset of walking and language development are linked.” Claxton says her research has indicated that young infants have better control over their posture than ever thought possible. Infants she has studied who had just learned to stand were far more stable when they were given a toy to hold or a TV image to focus on. This happened despite expectations that their muscles weren’t mature enough to sustain stable standing for the periods of time observed.

“So there has to be more about balance control than just physiological factors,” she says. “I’m really interested in exploring what those are.”

Claxton asks whether an infant with a goal to achieve — such as focusing on a toy or looking at an image — could hit physical milestones earlier than if the baby had no such goals. And when applying this to special populations, such as infants who may have autism, she asks whether goal-oriented therapy could help prevent them from falling as far behind in their development.

“It would be interesting to see if this could be used as an easy therapy to help them create their stability — especially if it helps overcome muscle delays or other delays,” she says. “Sitting, standing and walking are all really important for a host of other developmental milestones, so maybe this could help.”

Brandon Keehn

Brandon Keehn, assistant professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences and psychological sciences, is working to explain the areas of strength as opposed to weakness associated with ASD. Understanding these strengths, he says, may provide insight into how people with ASD perceive the world.

“Instead of looking at areas where children with ASD have some sort of deficit, we also look at domains in which children with ASD excel relative to their typically developing peers, with the idea that these areas of strength may be more easily traced back to their origin in the brain,” Keehn says.

He is currently collaborating with Ulrike Dydak, associate professor of health sciences, in this work. They will study the brains of children with ASD with a new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine acquired with a $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

In an earlier article in Life 360, Keehn was dubbed the “autism cartographer” because of his brain-mapping work with infants and children with ASD (see article, “Mapping the Spectrum”).

He also is crossing discipline boundaries in current work with Alexander Chubykin, assistant professor of biological sciences. Their project on eye-tracking technology in mice is aimed at understanding learning and attention differences in ASD (see “‘Gifted’ Research”).

Emily Tyson Studebaker

Repeating an often-cited quote, Emily Studebaker says, “One of the most important messages may be that, ‘If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.’” The saying speaks to the myriad ways ASD can look, and the many varied behaviors there are among people on the spectrum.

Studebaker is well-versed in this variability in her role as a clinical assistant professor of speech-language pathology who treats children with ASD and teaches future professionals.

“Every person with autism has a unique set of strengths and challenges,” she says. “I have met people with amazing abilities as well as significant challenges. Focus on abilities and continue to build from there.”

As an expert on ASD and pediatric speech and language disorders, she finds ways for children on the spectrum to communicate effectively. Strategies include sign language and high-tech, speech-generating devices for those with significant difficulties. Studebaker leads the Adult Pragmatic Language Group, which focuses on those who are more verbal. This gives adults with social-communication challenges a place to discuss their experiences and practice everyday social skills.

“I think it’s easy for someone to get this stereotype notion of what ASD is or what it looks like, and we know it can be very different for everyone,” she says. “What is true for everyone is true for those on the autism spectrum. We’re all individuals, so it’s important to get to know each individual.”

Bridgette Tonnsen

You hear it a lot: “Early diagnosis is key.” And it is as true for ASD as it is for many other physical and mental health issues. But early diagnosis is an enormous challenge with ASD. Bridgette Tonnsen, assistant professor of psychological sciences, joined the cluster in 2015 to continue her work examining early indicators of autism and other anomalies, such as attention problems and anxiety.

Because research shows that brain plasticity is greatest in the first three years of life, the younger that infants can be diagnosed and treated, the better the odds that interventions will successfully change brain development with positive, long-term results.

“There is substantial evidence showing optimized behaviors in children who are diagnosed early and receive interventions early,” Tonnsen says.

To that end, Tonnsen studies potential ASD predictors in infants, such as how they respond to new situations and how their attention patterns vary. Tonnsen’s studies have shown that infants who have trouble shifting their attention from one thing to another have higher rates of autism later in life.

“It’s not a one-to-one predictor; it’s just one factor,” she says. “The outcome that everybody hopes for is that we’ll have either a task or a series of tasks that have really strong predictive value. What’s exciting to me is the potential to establish early, strong markers of risk so that children and families can be supported through early intervention.”

Tonnsen says the cluster’s interdisciplinary nature adds to her enthusiasm.

“To address this problem, people can’t operate in isolation,” she says. “We have to collaborate, share ideas and learn from each other. Purdue is providing an excellent model for how autism research needs to be done.”

All of the Pieces

Additional members of the Purdue Austism Cluster include: Edward (Ed) Bartlett, associate professor of biological sciences and biomedical engineering; John (Jay) Burgess, associate professor of nutrition science; Alexander Chubykin, assistant professor of biological sciences; Ulrike Dydak, associate professor of health sciences; Rebecca McNally Keehn, adjunct assistant professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences; Marguerite O’Haire, assistant professor of human-animal interaction; Mandy Rispoli, associate professor of educational studies; Amy (A.J.) Schwichtenberg, assistant professor of human development and family studies; Amanda Seidl, professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences; and Oliver Wendt, assistant professor of educational studies and speech, language, and hearing sciences.

More Life 360 Stories

Research

- Five Tips for Parents of ASD Children

- Happiness Down to a Science

- Research Piece by Piece

- ‘Gifted’ Research