Purdue’s I-EaT Research Lab examining swallowing and speech in children with cerebral palsy

Georgia Malandraki

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

Understanding the role head and neck muscles play in eating and talking for children with cerebral palsy (CP) is a research effort led by Georgia Malandraki, professor in the Purdue University Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, and her I-EaT Lab. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine, and the Purdue College of Health and Human Sciences.

“More than 50% of children and adults with cerebral palsy may have speech, feeding and swallowing difficulties,” Malandraki said. “Although there has been a lot of research on the gross motor and hand functions of this population and how to best rehabilitate them, there has been much less work on the underlying mechanisms that cause feeding, swallowing and speech difficulties. This has limited our treatment options for these children and was a gap that we wanted to address.”

Speech difficulties can result in children and adults with CP not being understood; feeling isolated; and having reduced academic, social and employment fulfillment. Swallowing difficulties can also lead to serious consequences, such as being undernourished, dehydrated or in severe cases, developing respiratory infections (pneumonia) from foods and liquids not being safely swallowed. These types of difficulties — swallowing and speech — may also co-occur.

Most of the available treatments for swallowing and speech difficulties in CP are compensatory in nature and mostly address the symptoms, according to Malandraki. For example, simple changes in the child’s head and neck position during meals can aid in swallowing, and specialized, padded eating utensils could be an easy investment for families if a child with CP is having feeding issues. Malandraki added that making meals with softer, easier-to-swallow food, such as a fruit smoothie instead of fruit that needs to be chewed, is another simple strategy when children have difficulty chewing. Speaking slower or using exaggerated mouth movements are some common speech strategies as well.

“To be able to effectively improve the speech and swallowing functions of children and adults with CP, it is first imperative to understand how their muscles and brains work so we can use that information as we develop new treatments that will not just focus on the symptoms,” Malandraki stated.

Understanding underlying mechanisms

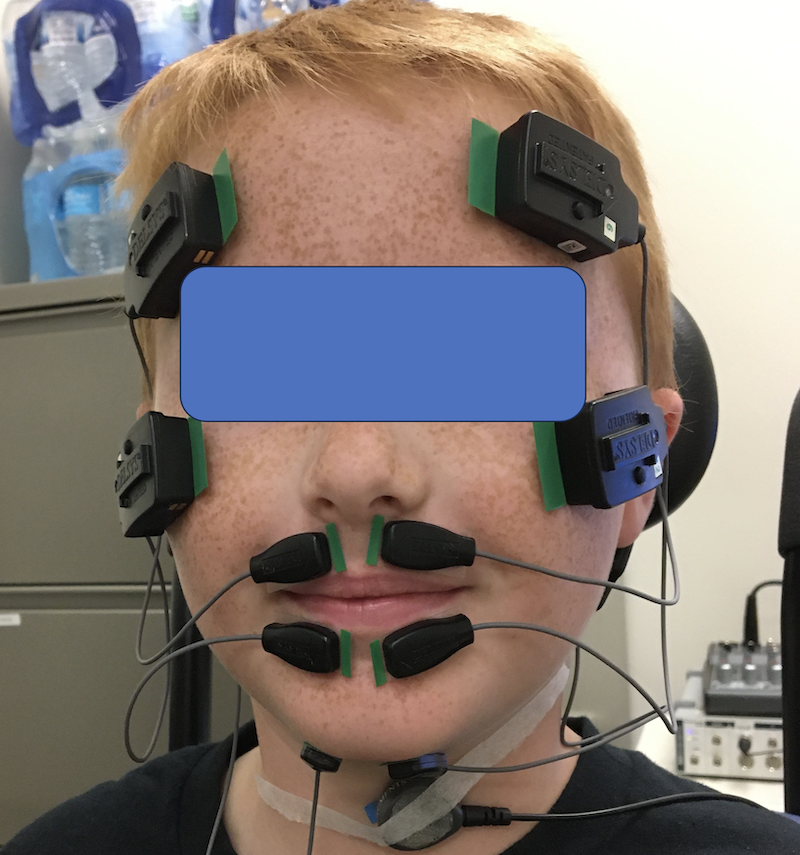

A child wears small muscle activity readers on their face to study how muscles activate during eating and speech tasks.

Through electromyography (small muscle activity readers), Malandraki and her team measured the head and neck muscle activity in 16 children with CP ages 7-12 and 16 children without the condition but the same ages.

The children with CP were tested at two sites, Malandraki’s lab and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. All had unilateral CP, a form of the condition where one side of the body is weaker than the other due to brain lesions affecting primarily one side of the brain. These children are usually more physically functional than children with more severe types of CP, such as quadriplegic CP, where both sides of the body are affected.

The children were able to feed themselves, and they were given a variety of food and liquids to swallow and were also asked to complete simple speech tasks. Through sensors attached around the mouth and under the chin, the researchers first found children with CP use these muscles much more than children without CP for both swallowing and speaking. This over-activation means these children were spending more energy to eat and speak than the typically developing control group.

“They show increased amplitude of muscle activity, indicating a lot of muscle effort,” Malandraki said. “So, they’re expending a lot of energy on both sides — the affected and unaffected — of the head and neck to be able to do simple tasks, such as eat, swallow and speak.”

For swallowing testing, the children were given sips of water to drink and pudding and pretzels to eat. Repetition of simple sounds and words was also requested. While used differently, the same muscles — perilabial (around the lips) and submental (under the chin) — are in play for both tasks.

Along with how much the muscles are fired, the researchers looked at timing — how quickly do the muscles react, and how long are they being contracted during a task? Swallowing and speech both require very delicate muscular coordination and timing. This biomechanic dance is easy for most but for children with CP, the steps can be arduous.

“What we saw was that in addition to using more muscle activity, they also used the muscles with less coordination between left and right sides compared to the typically developing group,” Malandraki said. “Our findings show that there may be a muscle coordination issue in some of these children. They can contract the muscles but have a hard time isolating the specific muscles that they need for a specific task.”

Recently published in the Journal of Neurophysiology, the work can inform evaluation processes and improve treatments for the children as they grow and develop.

“We want to better understand what the underlying mechanisms of the speech, feeding and swallowing difficulties that we see in these children are and also what are the interactions between speech and swallowing,” Malandraki said. “We are interested in finding more about a potential cross-system interaction between these two vital functions that both share many of the same mechanisms and muscles in the head and neck but use these muscles a little bit differently — or they’re supposed to use them a little bit differently for each function.”

Brain analysis results next

The study also collected magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the brains of children with CP and their typically developing peers. Since CP is typically caused by lesions on the brain formed during infancy or even while in the fetal state, this arm of the work is being analyzed now and will reveal neurological understanding of how children with varying levels of CP swallow and speak.

Tackling potentially life-threatening issues for children with CP is a difficult task because no child with the condition is like another. In her work, Malandraki said the severity of CP and of the speech and feeding profiles within the 16 children tested for the recent work ranged widely. Studying data gathered from muscle and brain MRI scans will help understand how some of these children can develop better swallowing and speech skills than others, and give us insights into how children and their families can adapt as the children grow into teenagers and young adults.

“Hopefully we can use these findings to develop treatments that will target these mechanisms,” Malandraki explained. “Most current treatments are not improving their speech and swallowing to the level that hopefully they could if they were based on their underlying mechanisms. Our work is trying to change that.”

Malandraki is currently expanding this work to other neurological populations to guide physiology-based treatment development for debilitating swallowing and speech disorders across the life span.