Saving more lives: International collaboration with Purdue Life Science MRI Facility aims to increase ‘life’ of kidneys for transplant

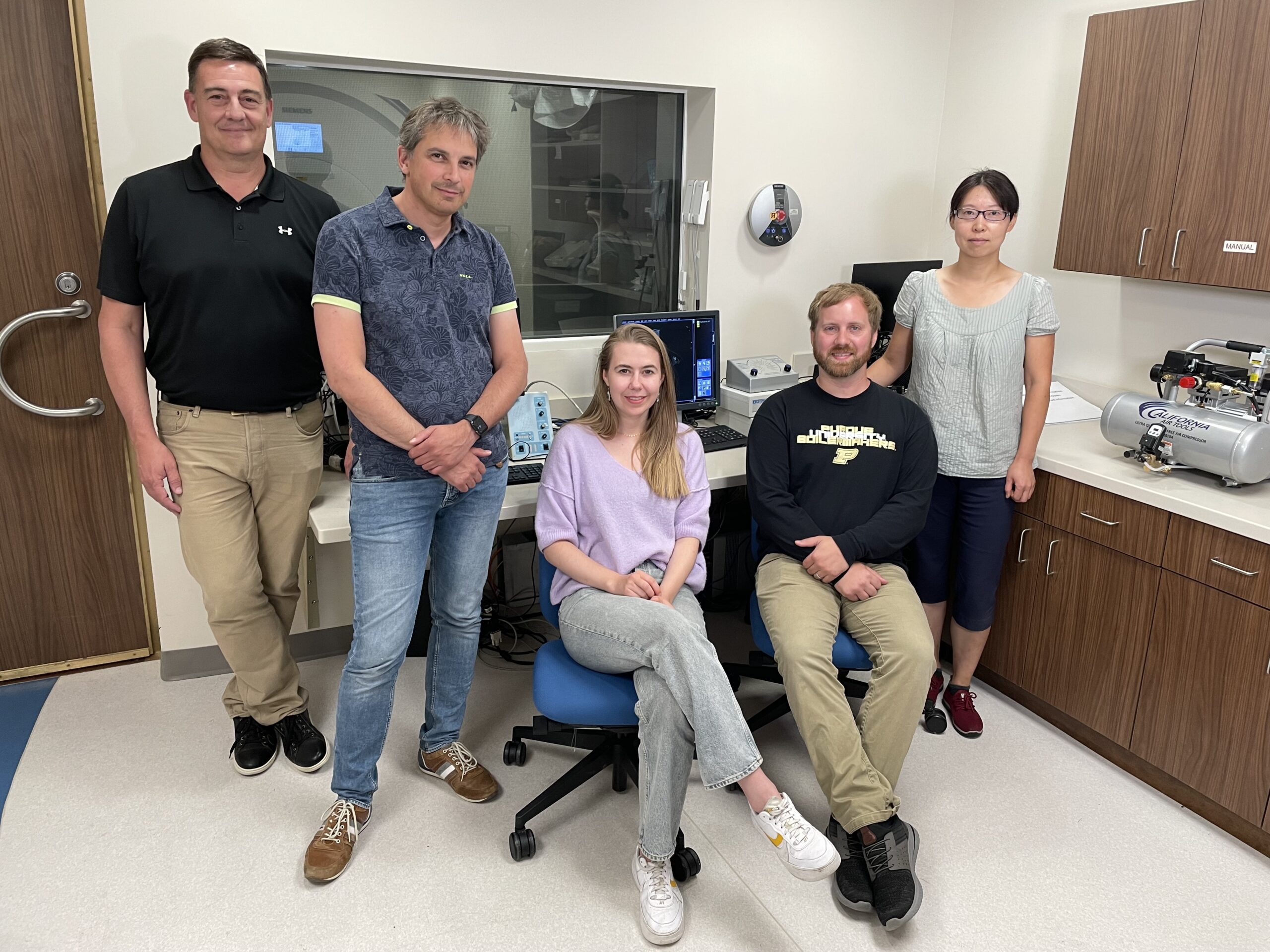

Members of a research collaboration between Purdue health sciences, 34 Lives and University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands included, from left, Chris Jaynes, CEO of 34 Lives; Dr. Cyril Moers, transplant surgeon and assistant professor in the University Medical Center Groningen; Veerle Lantinga; one of Moers’ students; Nathan Ooms, MRI technologist and Xiaopeng Zhou, operations manager of the MRI Life Science Facility.Tim Brouk

Written by: Tim Brouk, tbrouk@purdue.edu

When someone needs a kidney, every second counts. But each year, thousands of donated kidneys never make it to their destination in time. Last year, nearly a third of the 20,000 kidneys recovered for transplant in the United States were discarded due to transportation difficulties or other delays, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Those organs could have potentially saved 6,000 lives. That’s why an international team of researchers, including staff and faculty from the Purdue University School of Health Sciences, is working to find a solution.

The problem: most doctors won’t work with a kidney that has spent more than 20 hours outside of its donor. But a 2020 study found 493 out of 1,103 (47%) discarded kidneys were, in fact, still healthy enough for transplant. So how can you tell If an organ is healthy enough to last longer outside of its donor? That’s where the collaboration between the Purdue Life Science MRI Facility and 34 Lives, a company dedicated to rescuing discarded kidneys with a lab in West Lafayette, came in.

Dr. Cyril Moers, a transplant surgeon and assistant professor in the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, along with six of his students are trying to solve the problem, but they needed more kidneys to study.

“We would get one kidney every three months or so. We needed to do at least 25 (for the research), and it would have taken us years,” said Moers.

They found greater access in the U.S. But if they traveled here, they would also need access to an MRI scanner like the one they use in their own lab more than 3,600 miles away. The goal: to check for biomarkers that reveal the viability of the organs in order to eventually redirect discarded — but still healthy — kidneys to patients. A simple Google search linked them to the Purdue Life Science MRI Facility and 34 Lives.

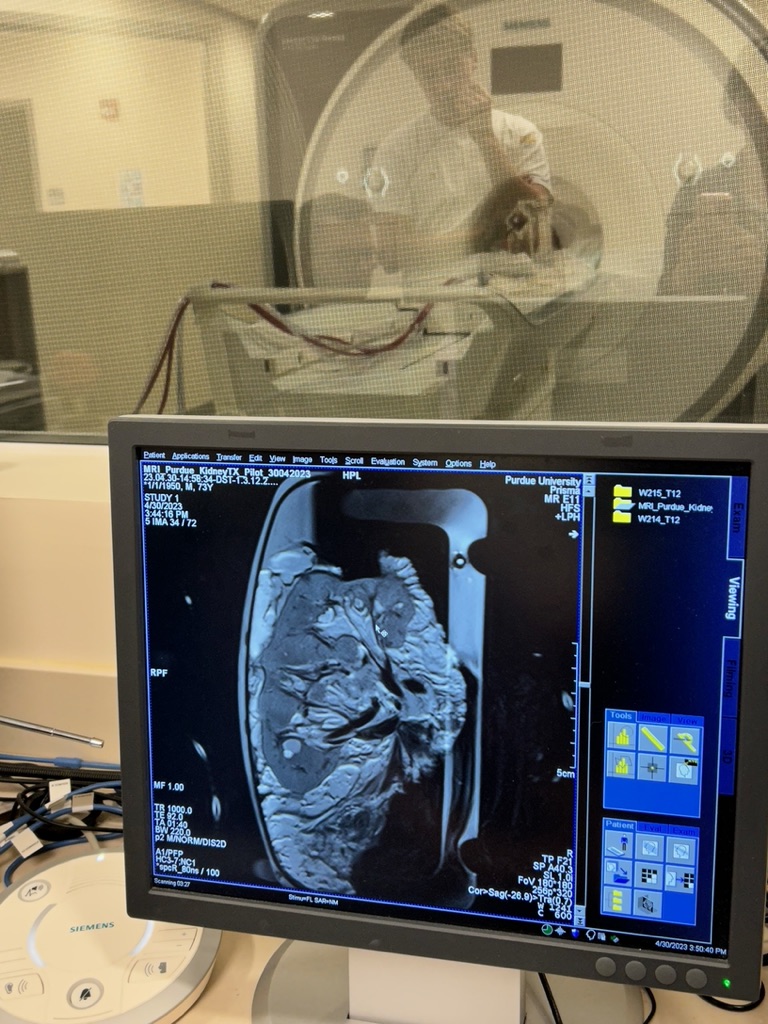

An MRI scan of a human kidney is displayed in the control room of the MRI Life Science Facility.

The European researchers arrived in early May and just finished scanning their 30th kidney in mid-July. Through the MRI images, the team was able to check the kidneys’ oxygen, sodium and potassium content while watching out for fibrosis, or thickening of the tissue. The data is now being analyzed back in Groningen.

Chris Jaynes, CEO of 34 Lives, was instrumental in supplying the kidneys for research. The work will be a game-changer for his continued goal to reduce the number of discarded kidneys in the U.S. which means thousands of organs can be saved and, in turn, save the lives of the patients.

“The collaboration has been amazing. I think it’s really helped us move the needle faster with the experience these guys bring from the Netherlands. It’s been a great partnership,” Jaynes said. “We look forward to a long and continuing collaboration with the Groningen researchers and the Purdue MRI Facility.

“The overall goal is to save lives. That’s what we’re all here for. That’s why this partnership has worked so well — we’re all aligned on the same mission.”

This work was funded by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. The kidneys were made available by 34 Lives and six Midwest organ procurement organizations.

How it works

Nathan Ooms, a graduate student in the School of Health Sciences and a technologist at the Purdue MRI Facility, said the various scanning techniques digitally dissect each kidney as the researchers look for biomarkers that hint at the organs’ viability. Yellows and greens highlight the health of each organ.

“Most of the techniques we’re trying here are noninvasive, which is the biggest benefit to MRI,” Ooms explained. “We can view a lot of these biomarkers non-invasively. We won’t need a biopsy.”

Another reason to scan kidneys is to protect against biopsy damage. In the U.S., kidneys must receive biopsies to ensure their health. However, sometimes the biopsy removes too much tissue and therefore kills up to a third of the organ’s viability.

“Doing this (checking biomarkers) in the MRI is great because the kidney can keep its native function,” Jaynes said. “You can look inside it without actually poking it. It gives you a lot of really interesting information that we couldn’t have normally gotten. We wouldn’t have been able to replicate this, probably, anywhere else in the country in terms of access and other support mechanisms in place.”

Time is of the essence

Jaynes opened his business in West Lafayette because of its proximity to Purdue’s research collaborations and its airport. Even today, many kidneys are put on ice in an Igloo cooler and flown to the destination. Due to the complications of the transplant and difficulty in finding matches, most surgeries in the U.S. involve kidneys transported across state lines. In the U.S., only about 10% of kidney surgeries have a live donor in the same hospital as the recipient, according to Jaynes.

Once the viable kidneys are found, the organs are hooked up to machines to keep them alive with the goal of eventual transplant.

“We’re trying to mimic the in vivo situation outside the body. By doing that, the kidney starts to work again, produces urine, and we can assess the kidney,” said Veerle Lantinga, one of Moers’ students who spent hundreds of hours scanning kidneys this summer.

Going Dutch

As the researchers from the Netherlands departed for home to continue their work, they leave with new collaboration partners in West Lafayette. The experience of working with their American counterparts who are equally dedicated to kidney and human health research was mutually beneficial.

“They were very welcoming, and before we knew it, we had a joint project,” Moers said. “I’m still fascinated by the fact that we could actually do this. I love collaborations. … It’s provided me with a lot of energy and new ideas.

“We were lucky to have found these partners. Without them, I couldn’t have done this project. It was only realistic here with these people.”

Ulrike Dydak, professor of health sciences and director of the Purdue Life Science MRI Facility, called the collaboration a “perfect symbiosis” between Purdue, 34 Lives and the Dutch researchers. The project also showed the versatility of the Life Science MRI scanner.

“At our facility, it was a first, definitely,” Dydak said. “We had scanned dead organs before, but having a viable organ in the scanner to not only get anatomical images but to measure its function was the special thing about it. It’s being perfused and being kept as if it was in a human body with all this technology, and we were still able to scan it.

“This is very special.”

U.S. kidney transplants by the numbers, according to the National Kidney Foundation

- 786,000 — estimated number of patients living with kidney failure, 2021

- 88,607 — patients on the national kidney transplant waiting list, 2023

- 25,498 — kidney transplants, a new national record, 2022

- 12 — people that die each day waiting for a kidney transplant, 2022

- 10 — donated kidneys discarded daily due to not reaching patient, 2022