HHS Parkinson disease research extends to patients and their families

Written by: Tim Brouk

Parkinson disease affects millions of Americans, yet there is still much mystery behind the debilitating and incurable disease.

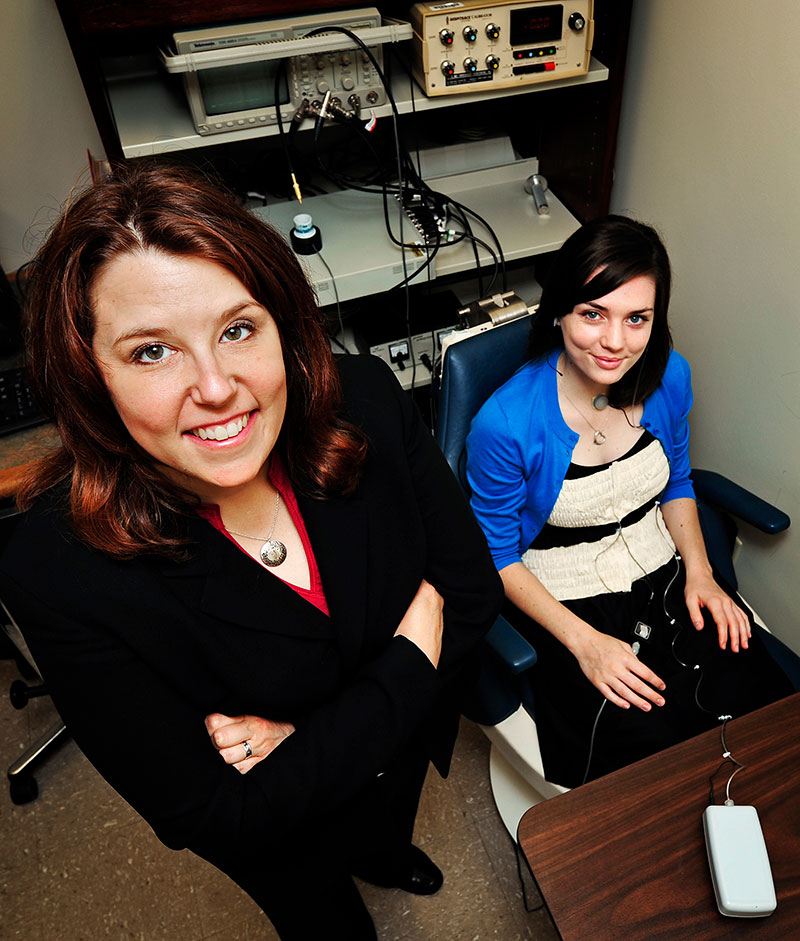

Symptoms and progression of the disease are highly variable from person to person. While we often talk of curing Parkinson disease, it is critical to consider how to improve quality of life for people living with the disease. Purdue University College of Health and Human Sciences researchers like Jessica Huber, professor of speech, language and hearing sciences, and Jiayun Xu, assistant professor of nursing, have found key focus areas for better treatments, which will help patients live more fulfilling lives.

Communication-focused

The focus of Huber’s research is two acts most of us take for granted — breathing and speaking.

While not a visible symptom like trembling limbs, the speech of a person with Parkinson disease can be a serious issue. People with Parkinson disease tend to have weak, quiet voices; fast rates of speech; and slurred articulation. Difficulty being understood leads people with Parkinson disease to withdraw from social activities, resulting in isolation. Difficulty making their needs known also can lead to dangerous situations.

Individuals with Parkinson disease also have difficulties with breathing.

“One of the symptoms in Parkinson disease is rigidity, which results in muscles that are stiffer, harder to move,” Huber said. “This is true in the respiratory system, where it can be hard for people with Parkinson disease to inhale and take deep breaths.”

These issues then make speaking more difficult.

“The respiratory system is critical in speech,” Huber said. “It’s the gas in the system. It’s the power and pressure for speech. If you don’t have good pressure from the respiratory system, your voice is weaker; utterances are shorter. Speaking becomes much more effortful.”

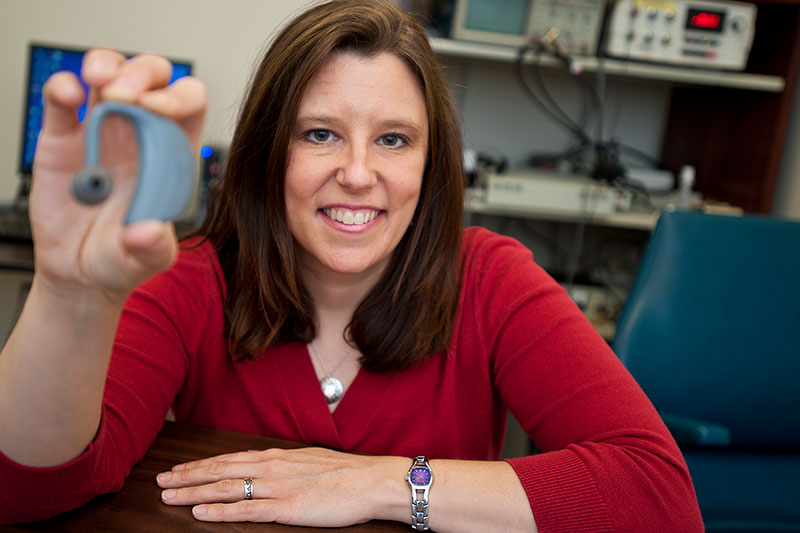

Huber developed a device to assist patients with Parkinson disease with communication. SpeechVive is a device worn around the ear that transmits multi-talker babble noise — a noise which sounds like many people talking at once — to the patient while they are speaking. The noise triggers the Lombard effect, a reflex that causes us to speak louder, clearer and slower in the presence of background noise. This alleviates three main concerns for communication in Parkinson disease.

Huber has completed several clinical trials of the SpeechVive device and found that it improves communication in most patients who use it. Further, after using the device for eight weeks, people with Parkinson disease use their respiratory systems more like healthy older adults, potentially reducing the work of speaking.

Huber’s laboratory is collaborating with Michelle Troche at Teachers College, Columbia University to study a second device: the Expiratory Muscle Strength Trainer 150. When breathing through the device, patients have to overcome a resistance from a spring-loaded valve.

“As you breathe out, it’s like doing bicep curls for your respiratory system,” Huber explained. “This device helps patients strengthen their cough — another function most people take for granted.”

Huber said people with Parkinson disease who have a weak cough are at risk for choking and suffocation. With Troche, Huber and her laboratory are investigating if this device could also improve communication through its effect on the respiratory system.

Family-focused

There is no blueprint for talking to a loved one suffering from Parkinson disease about critical medical issues, especially at the end of life.

This summer, Jiayun Xu, assistant professor of nursing, will be working with Indiana’s Parkinson disease community to create an end-of-life resource for family members to use in helping mitigate those difficult conversations as well as remind them about important topics to discuss with doctors. Once developed, the resource will be available to patients and family members.

“It’s always been my goal to help families be better prepared to make difficult medical decisions and communicate better about end-of-life topics,” Xu said. “We want to figure out what would be helpful for people to have better conversations and when it would be appropriate to give them this type of resource.”

Another research project for Xu concentrates on nurses who also care for their older family members with various illnesses such as Parkinson disease. She studies how being a “double duty caregiver” affects job performance and well-being.

Being a “double duty caregiver” as a nurse or other healthcare worker may have well-being and work consequences, Xu said, not only for their mental health but also career trajectory.

“We are looking at how nurses’ individual well-being is impacted as well as their work performance,” Xu said. “Everyone goes to the nurse in the family when something happens that’s medically related. The family asks for help and expects nurses to be caregivers. When nurses cannot help or do not meet family expectations, that’s when problems can happen. There is an interesting dynamic between what nurses can do professionally and how their knowledge can/cannot be applied to a family situation. Family caregiving affects nurses personally and professionally. It can take a mental and physical toll.”

‘We are circular’

As College of Health and Human Sciences associate dean for research, Huber sees her colleagues investigating Parkinson disease from numerous angles. Cell science to animal models to human models to intervention to risk factors to counseling — all of these areas work together to test data and create the next hypotheses. With a disease as complex and difficult as Parkinson disease, there must be more avenues than the classic “bench to bedside” path. Molecular research informs how Huber and Xu talk to patients they work with. Similarly, their research informs the science into causes, drug treatment development and other bench work with Parkinson disease. “In the college, it’s this loop. We are circular,” Huber said. “The continual feedback between the basic science to translational and clinical science then back to basic science is what really makes the Parkinson research community strong in HHS and Purdue more generally.”