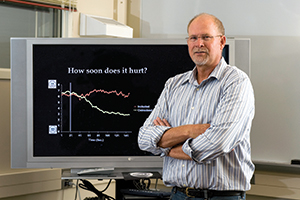

"We all feel the pain of ostracism just about equally, no matter how tough we may be." - Kip Williams (Photo by Charles Jischke)

An entry-level account executive not invited for the weekly lunch outing. A child not being included in a game of basketball during recess. From children to the elderly, from schools to offices, most people know the feeling of being left out or excluded.

For Kip Williams, a chance Frisbee game led to an increased curiosity about exclusion. Now, as a professor of psychological sciences, Williams is helping scientists better understand how ostracism works in the brain. He is also working with community groups to provide support for those affected by this social phenomenon.

Williams was working as an assistant professor of psychology at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, when an outing to the park with his dog turned into something much more. He was sitting on the ground when a Frisbee rolled and hit him in the back. He tossed the Frisbee back to its owners, who then began to engage Williams in their game. But after just a few tosses, they stopped including him.

"At first, it was sort of funny," Williams says. "But when it became clear that they were not going to include me again, I felt foolish, awkward and hurt. I felt ostracized."

That Frisbee incident further sparked his academic interest in the causes and effects of ostracism, which is defined simply as being ignored and excluded.

"Typically the term implies a situation in which a group is shunning an individual," Williams says. "It can also describe the so-called silent treatment, where one person ignores another or a group excludes another group or even an individual rejects a group."

Ancient Athenians coined the word "ostracism." They wrote the name of the person they wished to banish on shards of clay, known as ostraca. But the phenomenon appears to have existed for as long as there have been social animals. Williams says many researchers believe the fear of being ostracized helped civilizations emerge.

"Fearing exclusion and being ignored within a group causes people to act within social norms," he says. "Ostracism emerges for acting outside of these social norms. Knowing those possible outcomes keeps people acting in a civilized manner."

Ostracism is not restricted to humans. Social animals from buffalo to bees can ostracize members of their groups. Williams says the reason for the ostracism is that it strengthens the groups because the animals get rid of any member who threatens their success.

Kip Williams, professor of psychological sciences, has found that ostracism resonates in the same area of the brain as physical pain, inciting anger and sadness. (Photo by Mark Simons)

The Pain of Rejection

Williams' major focus in his ostracism research is how it affects people — particularly the impact on their brains, emotions, thinking and behavior. His research shows that ostracism resonates in the same area of the brain as physical pain and incites anger and sadness. This pain can be functional if it causes the person to evaluate the situation and decide if the best course of action is to change behavior or find another group in which to belong.

"We all feel the pain of ostracism just about equally, no matter how tough we may be," he says. "After the pain, a person tries to deal with the impact of the ostracism episode."

Williams developed a research tool to study the effects of ostracism in the lab. He re-creates his Frisbee game experience with a virtual tool called Cyberball wherein participants toss a virtual ball with two other players represented by animated characters on a computer screen. Some of the participants are ostracized — they receive the ball once or twice at the beginning of the game, but never again.

"It might surprise people at just how angry or sad the individuals became when they were ostracized, even in this simple virtual game," Williams says. "This is experimental manipulation; it has nowhere near the same emotional impact as much larger situations such as when a father tells his son he is dead to him. Cyberball involves a small manipulation with large effects."

Williams says they have done other studies in which people report experiencing an average of one event per day where they feel rejected by groups or society. This can lead to a lack of meaning in and control over their lives. Even such seemingly small events can trigger strong emotional reactions.

While anyone can be ostracized, some are more at risk for chronic or daily ostracism, including minorities or those with mental or physical disabilities.

"When dealing with ostracized children, the key for parents is to be aware of what is going on," Williams says. "Once there is awareness, then the adult can help the child figure out a strategy for dealing with the ostracism." (See "Q&A about Ostracism" for best approaches to dealing with ostracism in children.)