| RELATED WEB SITES |

| * Susan Curtis |

| * Colored Memories |

July 1, 2008

Historian applauds black journalist, diplomat who history forgot

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - |

Lester A. Walton, who also was one of the first African-Americans to work for the Democratic National Committee and as U.S. minister to Liberia before and during World War II, had been missing from American history books, said Purdue University historian Susan Curtis.

"He knew American celebrities, writers and businessmen," said Curtis, a professor of U.S. history and American studies. "He played a significant role in race relations. He advised U.S. presidents and industrialists. He was a New York City commissioner for human rights who was instrumental in desegregating housing in the city. So why don't we know this man? Internet searches reveal nothing, and the few books he is briefly mentioned in do not tell his story.

"The easy answer is he was forgotten because he was black. Certainly race is part of the mystery, but politics, archival accidents and the behind-the-scenes nature of his work also contributed to his disappearance."

|

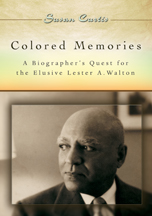

Curtis is the author of "Colored Memories: A Biographer's Quest for the Elusive Lester A. Walton" ($39.95), which will be published July 10 by University of Missouri Press. Walton died in 1965.

Walton was first known as the music and drama critic for New York City's black newspaper, New York Age. He made some of the first stage, screen and concert performers, such as Bert Williams, George Walker, Bob Cole and Rosamond Johnson, famous when he covered their shows or wrote about their lives and style.

Decades after he left the New York Age, he spent years calling and meeting with corporate and broadcast executives to convince them to feature more African-American performers.

"As the founder of the Coordinating Council of Negro Performers, Walton kept steady pressure on those who chose programming for television and radio, and when his work succeeded, others took the bow before the footlights," Curtis said.

Walton worked for the Democratic Party in the 1920s and 1930s. He was publicity director for the black division of the Democratic National Committee in 1924, 1928 and 1932. At that time, most African-Americans were affiliated with the Republican Party, known as the party of Abraham Lincoln, Curtis said. Walton worked behind the scenes to promote the Democratic Party to African-Americans, and, as a result, more African-Americans began to change their affiliation.

Walton also was U.S. minister to Liberia from 1935 to 1946. During this time he facilitated American business interests in rubber production and laid the foundation for the United States to establish a military base on the African West Coast for World War II.

"Walton retired shortly before he died, and a NBC executive sent him a telegram to thank him for everything he did," Curtis said. "Interestingly, the message also said that Walton would not be forgotten."

Curtis focused her research on why Walton has been forgotten. She found that interracial and intraracial conflicts played a role. Problems arising from slavery, racial discrimination and extralegal violence also led to the suppression of Walton's life story.

"The rhetoric of American democracy has not matched our behavior," Curtis said.

Curtis became interested in Walton while working on a biography of Scott Joplin. She read many of Walton's columns about black stage and music, looking for information about the ragtime composer. She became frustrated when Walton excluded Joplin from articles on musicians in Harlem.

"There were times I thought, 'Who is this guy?' " Curtis said. "He had so much control over the story about Joplin and other artists at the time, I had to know more about him."

Curtis details her search for Walton and explains why she could not write a conventional life-and-times biography of Walton. Some information on his youth in the late 1800s and on his parents, both born before the Civil War, could not be traced. Walton's reticence about his family also thwarted a biography.

"This is an experimental piece in which I narrate my evolving relationship with Walton while piecing together significant events in his life," Curtis said. "Most historians try to remain detached from the subject they write about, but that's nearly impossible. We choose what we write about and are thus implicated in the story. I wanted to say that explicitly in this book."

Curtis received funding from the College of Liberal Arts' Center for Humanistic Studies and Faculty Research Incentive Grants. She also has written "Dancing to a Black Man's Tune: A Life of Scott Joplin."

Writer: Amy Patterson Neubert, (765) 494-9723, apatterson@purdue.edu

Source: Susan Curtis, (765) 494-4159, curtis@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: Journalists interested in review copies can contact Beth Chandler at the University of Missouri Press, (573) 882-9672, chandlerb@umsystem.edu

To the News Service home page

If you have trouble accessing this page because of a disability, please contact Purdue News Service at purduenews@purdue.edu.