| RELATED INFO |

| * Full Environmental Research Letters article |

September 8, 2009

Research suggests urban sprawl, wet falls and winter affect severe weather

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - |

As large urban areas continue to expand, they appear to influence tornadoes and other severe weather, research suggests. Cities could be even more at risk if located in a region experiencing a wet fall or winter, according to researchers from Purdue University and the University of Georgia.

One study by professors Dev Niyogi at Purdue and Marshall Shepherd at Georgia found that drought in the fall and winter appears to decrease the number of spring and summer tornadoes in the U.S. Southeast. It is possible that particularly wet fall and winter seasons may lead to more tornado activity but this is less conclusive and is the subject of ongoing research.

The research could eventually contribute to a system for predicting the severity of tornado season in the same way meteorologists and climatologists project hurricane season.

The drought study, which appeared in the April-June edition of the journal Environmental Research Letters, stemmed from an earlier, NASA-backed examination of a rare tornado in Atlanta on March 14, 2008. The tornado study also was done jointly by Niyogi and Shepherd, whose research focuses on understanding relationships between urbanization and land cover in general, and weather and climate patterns.

The 2008 study found Atlanta’s sprawling urban landscape, a prolonged drought in the region and scattered rainfall just before the storm combined to intensify and pinpoint the tornado. The twister, with 130-mile-per-hour winds, killed one person and caused $250 million in damage.

"As we become more urbanized, we will probably start to see tornadoes in more urban areas," said Niyogi, a Purdue earth and atmospheric sciences associate professor and the Indiana state climatologist. "I don't think what happened in Atlanta is unique."

The Atlanta tornado is one example of possible urban weather effects the scientists have identified. Niyogi's Purdue lab is researching indications that Indianapolis may be soaking its neighbors by shedding thunderstorms.

The future may bring more weather effects like those as urban areas expand and if global climate change, as scientists predict, results in additional severe weather events worldwide.

"You have thousands of storms every year," Niyogi said. "But if you look at documented incidents in the last 20, 25 years, we traditionally have not seen a lot of severe weather activity such as tornadoes in urban areas."

In part, that’s because cities have been relatively small targets.

"It's like throwing at a dart board and trying to hit the same point every time," Shepherd said.

But a growing number of sprawling metroplexes like Atlanta, Indianapolis, Houston and St. Louis, as well as burgeoning urban areas across the globe in countries like India and China, appear to have reached sizes where they’re not only big targets, but also can actually influence the weather, sometimes tragically.

In Atlanta, the tornado was expected to be a welcome rainy respite from the drought. The urban twister was surprising enough that Niyogi and Shepherd approached NASA with a proposal to examine the causes.

The researchers employed cutting-edge satellite data from NASA and the Japanese space agency to model the storm in reverse on supercomputers from ITaP, Purdue’s central information technology organization, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Niyogi, Shepherd, Purdue research scientist Anil Kumar and graduate student Ming Lei modeled the storm several times over, studying the influence of parameters such as the urban area’s size, soil moisture and temperature, cloud cover, and rainfall to see how they influenced each other and the overall weather.

"We kind of re-engineered the storm," Shepherd said. "We can run that model and get different realizations. It's just like an experiment in a lab."

Computing power also permitted the researchers to model at finer-than-normal scales of 1 to 5 kilometers, Niyogi said. The study is among the first to model an urban area’s effect on the weather in such detail. Typical weather modeling is done at scales more like 10 to 30 kilometers.

In the Indianapolis area, Purdue researchers noticed rural areas around Indianapolis, particularly downwind, consistently receive more rain than the urban center. Lei, a doctoral student in Niyogi's lab, said it could be that warming of the air over the city causes storms to hold water until reaching cooler rural areas. The effect is like the release of a warm breath resulting in condensation on a cold winter’s morning.

Lei's modeling indicates that doubling or tripling the size of Indianapolis might drop even more rain outside the city.

Niyogi and Shepherd cautioned against generalizing the weather effects of city size at this point. But both say the studies point to the need to consider further the role urban growth and other land-use changes, as well as precipitation trends and soil moisture, play in the regional weather and climate. That’s especially true now that high-performance computing and high-resolution satellite data make modeling specific metropolitan locales in fine detail feasible, the researchers said.

The researchers also are examining data from a May 30, 2008, tornado in the Indianapolis area, which devastated an apartment complex and shopping center. They plan to look at Chicago and Milwaukee to get a feel for how multiple cityscapes impact weather patterns.

The Atlanta study indicated that scattered rain in Alabama and northwest Georgia 48 hours before the tornado may have sent the storm over a patchwork of wet and cool, dry and warm areas on its way to Atlanta. That boundary hopping increased the storm’s intensity. Then, when the storm moved to the surrounding rural area's boundary with Atlanta, the heat-retaining effects and rough surface of the city's buildings and streets may have intensified it further. Niyogi said the drought and the urban landscape didn't cause the tornado as much as further energize an already intense storm and pinpoint its worst effects.

The new study by Shepherd, Niyogi and Georgia's Thomas Mote focused more generally on how drought conditions at different times of the year may affect tornado formation. The researchers analyzed 55 years of data on severe thunderstorms and tornadoes provided by the Storm Prediction Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They also used storm data from the National Climatic Data Center, along with rain gauge and NASA satellite data on droughts. The study doesn't address the question of why dry falls and winters are followed by less tornadoes, but the relationships it uncovered are striking, Shepherd said. The researchers are now replicating the study in more tornado prone regions like Tornado Alley, which runs from South Dakota to Northern Texas.

Writer: Greg Kline, science and technology writer, Information Technology at Purdue

Sources: Dev Niyogi, 765-494-6574, climate@purdue.edu

Marshall Shepherd, 706-542-0517, marshgeo@uga.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: An animation of the Atlanta tornado modeling results is available at:

mms://video.dis.purdue.edu/BNS/ITAP/itap_nasa_090827.wmv

ANIMATION CAPTION:

A NASA animation based on a study by Purdue and University of Georgia scientists shows how, in the

days leading up to March 14, 2008, pockets of rain fell between drought-ravaged areas that saw no rain, setting up boundaries of dry and moist air. These boundaries, along with urban-rural land cover boundaries, produce circulations and rising air similar to a sea breeze. They may also serve as localized regions of enhancement for existing storms or initiation of new storms. Modeling studies suggest that these boundaries were a factor in the storms that produced the Atlanta tornado. Sprawling cities in the United States and across the globe may now be large enough to make them more likely to experience severe weather, a rarity in the past, and even to affect the weather for the worse under some conditions. Credit: NASA/Ivy Flores

Animation available at: mms://video.dis.purdue.edu/BNS/ITAP/itap_nasa_090827.wmv

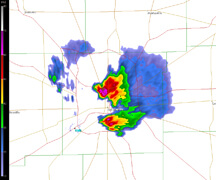

PHOTO CAPTION:

A frame modeled from satellite data shows a thunderstorm splitting apart, or "bifurcating," as it passes over Indianapolis before reassembling and soaking the downstream area after moving beyond the city. The city's sprawl may have an influence on the amount of rain the area around it receives, which is consistently more rain than the urban center, Purdue research indicates. Credit: Purdue/Ming LeI

A publication-quality photo is available at: https://www.purdue.edu/uns/images/+2009/NyogiWeather.jpg

A seasonal-scale climatological analysis correlating spring tornadic activity with antecedent fall–winter drought in the southeastern United States

Marshall Shepherd1, Dev Niyogi2 and Thomas L. Mote1

1 Climate Research Laboratory, Department of Geography, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, USA

2 Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA

Using rain gauge and satellite-based rainfall climatologies and the NOAA Storm Prediction Center tornado database (1952–2007), this study found a statistically significant tendency for fall–winter drought conditions to be correlated with below-normal tornado days the following spring in north Georgia (i.e. 93% of the years) and other regions of the Southeast. Non-drought years had nearly twice as many tornado days in the study area as drought years and were also five to six times more likely to have multiple tornado days. Individual tornadic events are largely a function of the convective-mesoscale thermodynamic and dynamic environments, thus the study does not attempt to overstate predictability. Yet, the results may provide seasonal guidance similar to the well known Sahelian rainfall and Cape Verde hurricane activity relationships.

To the News Service home page