January 12, 2005

New Purdue barn strives for cleaner, fresher air for livestock farms

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - A new state-of-the-art facility, cutting-edge equipment and the human nose are aiding Purdue University scientists' search for ways to minimize noxious smells and possible air and water contaminants from livestock barns.

|

The researchers are working with the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Pork Board to ensure that animal farms are as odor-free as possible and safe for animals and people, said Brian Richert, animal sciences professor. The studies revolve around testing different diets and management practices to determine how they contribute to aromas and other air and water pollutants from animal waste.

"Large livestock facilities don't fall under current emissions standards because no baseline data exists for such operations, and there is even less information on the odor issue," said Richert, one of the people leading the studies. "This is because it's very difficult to do measurements."

Richert and his co-investigators, including agricultural and biological engineering professor Albert Heber, said the 15,500-square-foot, 12-room Swine Environmental Research Building can hold 720 hogs and replicate actual conditions at a working farm. The only facility of its kind in the United States, the Purdue farms barn began operation this summer. The scientists said it will solve the issue of gathering emissions data.

|

"Replication is important to test abatement technology," said Heber, who has one of only six laboratories in the country that studies emissions connected with odor. "If you want to modify a diet, then we want to know if the new diet will affect emissions from a pig. To do this, you need at least two rooms with the new diet and two rooms with the old diet. This building allows proper replication."

Emissions of animal waste-caused pollutants that emanate from livestock facilities include particulate matter, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, which is a byproduct of ammonia. The latter three are considered greenhouse gases, which are at least partially responsible for global climate changes.

Monitoring of emissions at the Purdue swine research facility is performed unmanned around the clock. Samples of gas are picked up at 25 places in the barn using a new $50,000 device, purchased through a USDA grant, that measures ammonia and greenhouse gases.

Although the EPA doesn't regulate odors, it does restrict emission amounts of odor-causing chemicals. Any facility emitting more than 100 pounds per day of either or both hydrogen sulfide and ammonia must report it to the EPA. The fine for exceeding this amount is $27,000 per day.

Approximately 3,500 pigs can generate 100 pounds of ammonia per day, Heber said.

Though he uses sophisticated methods for sampling and measuring the chemicals that create odor, Heber uses the human nose to determine the nuisance factor.

The researchers bag the odor and then take the bags to campus where eight panelists each take a whiff. A $30,000 ofactometer dilutes the odor in the bag with odor-free air in order to determine how much smell is offensive.

"We determine each panelist's odor threshold." Heber said. "For example, in some cases we might have to dilute the odor 500 times before they can't smell it. For another person it might be 1,000 times."

Complaints from private citizens and municipalities, including several lawsuits against livestock farms, led to calls for setting emission standards and for methods to efficiently measure waste, odor and other pollutants, Heber said. Richert, Heber and their research teams are delving into the best ways to mitigate emission problems.

"There are several ways to measure ammonia, and we are using top-of-the-line, EPA-approved instruments that use a chemiluminescence method that mixes nitrous oxide with ozone to create a glow," Heber said. "We also use an infrared method and similar methods for hydrogen sulfide."

The 12 identical rooms at the facility house hogs that can be fed diets with varying ingredients. Different recipes can contribute to varying amounts of manure, urine, the various resulting chemicals and gases, and also animal growth.

Airflow in the barn research rooms is controlled and management of animal waste is varied to determine how various practices impact emissions into air and water. The temperature is controlled in a way as similar to an average large livestock barn as possible.

"The fans are computer controlled, so we know exactly the fan and the air exchange rates. Then we can sample the gases and determine exact emission rates for any compound we're monitoring," Richert said. "We've mimicked exactly what the industry has today, so we think we'll have the best data available."

The location of the barns - whether in a valley or on a hill or surrounded by trees or entirely out in the open - also must be considered when determining the effect of the particulate matter, chemical and/or odor a livestock facility is ultimately emitting, Richert and Heber said. The method used and how often livestock waste is disposed of also plays a part in air emissions and water pollution.

"All those things come into play," Richert said. "If a facility ventilated by fans has a tree line, a tree line can deflect everything up and dilute it. If there is no tree line, the fans can blow directly across a field or a road and the neighbors will smell it."

Combining all of the data from the research barn and from the bags gives the scientists ways to calculate how far away a livestock facility must be from a neighbor to minimize the odor, and also helps adjust management and feed practices to negate the facility's environmental impact, Heber said.

"We are addressing the odor nuisance problem, and this building allows us to measure odor concentration directly," he said. "If we know the odor concentration and the airflow through the fan, we can calculate the odor emissions. So we very carefully measure both the concentration of the pollutant in the air going out of the building and the air flow in the barn.

"We're establishing and refining methods and techniques that are being used around the country. Hopefully our measurement protocol will become the official EPA standard."

Although the Purdue Swine Environmental Research Building will be dealing only with pigs over the next two or three years, results may help cope with other livestock issues, and the facility itself someday may host studies on other farm animals, Richert said.

The current projects to study the impact of diet on odor, excretion and air emission, and to establish baseline emission data for swine facilities, are funded by USDA and EPA grants totaling $500,000 and another grant from the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for $1.3 million.

Writer: Susan A. Steeves, (765) 496-7481, ssteeves@purdue.edu

Sources: Brian Richert, (765) 494-4837, brichert@purdue.edu

Albert Heber, (765) 494-1214, heber@purdue.edu

Ag Communications: (765) 494-2722; Beth Forbes, forbes@purdue.edu

Agriculture News Page

Related Web sites:

Purdue Agricultural Air Quality Laboratory

Purdue Department of Animal Sciences

Purdue Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering

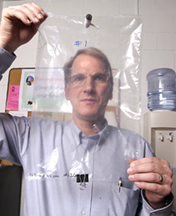

PHOTO CAPTION:

High-tech equipment is used to measure air and water pollution, including odor, that emanate from livestock farms. But for some of the data gathering, Purdue University researcher Albert Heber uses bags and human noses. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell)

A publication-quality photo is available at https://ftp.purdue.edu/pub/uns/+2005/heber-stinkbag.jpg

PHOTO CAPTION:

A mass of hoses and wires helps researchers like Brian Richert monitor the air quality at a new animal research center located northwest of the Purdue University campus. Each plastic tube draws air from several locations within a dozen hog pens. The tubes are connected to a computer that analyzes air quality. (Purdue Agricultural Communication photo/Tom Campbell)

A publication-quality photo is available at https://ftp.purdue.edu/pub/uns/+2005/richert-airsamp.jpg

To the News Service home page