Purdue News

Purdue News

Purdue News

Purdue News

March 1997

|

"The soil shows some striking and beautiful patterns, some of which look like primitive cave drawings or modern art, depending on the eye of the viewer," McFee says.

Micheli and McFee, who is president of the Agronomy Society of America (ASA), shared their analysis of both the soil and the art of the Aktar site at the ASA national meetings in Indianapolis in November.

What they found at Aktar is a soil formed from old sea, terrestrial sediments, wind-deposited silts and organic matter. Once formed, the Aktar soil was infiltrated by calcium carbonate and heaved around by frost and animal action.

Micheli had known about Aktar's strange soil formation for years, but didn't have the time or resources to study it alone.

"My major professor had found the site years ago when he was doing a mapping project," Micheli says, "and it was something I wanted to work on for a long time." McFee's interest and the chance to do joint research with Purdue gave Micheli the push to get the job done. Together Micheli and McFee reconstructed what must have happened in the last few million years.

The Aktar soils lie at the foot of a mountain called Matra, the highest in Hungary. Around 10 million years ago, before man walked on earth, the area was flooded by the Pannonian Sea, Micheli says. The sea water deposited thick layers of light-colored sands and clays.

"After the sea subsided, a warm, humid climate that persisted for long periods allowed the formation of reddish soils similar to some found in southern Indiana today," McFee says.

Along with the first humans came the Pleistocene equivalent of groundhogs, creatures that began digging burrows in the soil around Aktar, Micheli says. Back and forth, up and down, the animals tunneled and pushed the earth. Then they were gone.

Water and wind pushed red silty clay into the abandoned tunnels, Micheli says, creating red tubes of earth that wound up and down through the yellow and gray soil layers.

Then the Ice Age descended. Hungary was spared glacial ice sheets, but rainwater froze and thawed in the earth around Aktar, Micheli says. The resulting pressures squeezed the layers and tubes of sand and clay. It left a swirled and ripply layer cake of soil, pretty enough to hang on your wall.

Before she left Hungary for a visit to the United States, Micheli smoothed a section of the soil wall, slathered it with lacquer and pressed a lacquered canvas against it. Many hours later, when she pulled away the dried canvas, she had a three-dimensional portrait of the wavy soils of Aktar.

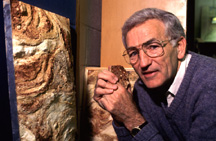

"I've been telling her (Micheli) that she should be framing more of these," McFee says as he holds up a framed bit of the Aktar wall.

She would consider creating more Aktar art, but the mining operation that opened the soil to human view may lead to its reburial.

"It was lucky and unlucky," Micheli says. "Because it was a mine, the soil was exposed, but then it was made into a landfill."

Farmers till similar soil near the site. If farmers plan to irrigate or to use fertilizers or pesticides on their land with the least possible environmental impact, they need to understand the peculiarities of their soil, McFee says. Formations such as the tubes of sand and clay at Aktar could change the way fertilizer or pesticides move through the soil -- and could increase chances for ground water contamination.

What McFee has learned in Hungary he can apply in Indiana. Aerial photographs of drought-stressed corn and soybeans suggest to Micheli and McFee that parts of Indiana have similar subsurface features, although so far no excavations have been done in those areas. If Midwestern farmers are truly tilling Aktar-like soil, a change in management could bring better harvests and cleaner environments.

Source: Bill McFee, (765) 494-4774; e-mail, wmcFee@dept.agry.purdue.edu

Writer: Rebecca J. Goetz, (765) 494-0461; e-mail, rjg@aes.purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; e-mail, purduenews@purdue.edu

Photo Caption:

Purdue agronomist Bill McFee, who studies soil formation, turns research into art

as he displays a canvas that contains a slice of the striking soil patterns found

near Aktar, Hungary. (Purdue Agricultural Communication Service Photo by Mike Kerper)

Color photo, electronic transmission, and Web and ftp download available. Photo ID:

McFee/Soilart

Download Here